Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Soundtrack To A Movement: African American Islam, Jazz, ...

Soundtrack To A Movement: African American Islam, Jazz, and Black Internationalism

Soundtrack To A Movement: African American Islam, Jazz, and Black Internationalism

Soundtrack To A Movement: African American Islam, Jazz, and Black Internationalism Richard Brent Turner

256 Pages

ISBN: 9781479806768

NYU Press

2021

The influence of Islam on African American jazz musicians post-WWII and the influence of those musicians in the spread of Islam in American cities are interrelated topics that, broadly speaking, are not part of most mainstream histories of jazz. Weave Black internationalism into the equation, that's to say how pan-global liberation/anti-colonial movements fed into the Civil Rights and Black Power struggles, and it should be clear that we are dealing with a book that breaks new ground in jazz studies.

Not that this is a jazz-dominated narrative, for Richard Brent Turner, Professor of Religious Studies and African American Studies at the University of Iowa, works on a broad canvas. In this relatively slim but densely packed tome, the author joins the dots between movements of people, the spread and growth of religious and musical ideas and the politization of the disenfranchised.

Charting roughly the period from bebop in the 1940s to free-jazz of the 1960s and 1970s, Turner demonstrates how Islam and jazz shared common traits that appealed to those seeking "subversive musical sounds and identities." As multiple voices in this book attest, conversion to Islam by jazz musicians and fans alike seems to have been as much an act of rebellion as it was the embrace of a pan-African/Asiatic identity.

To those unfamiliar with the history of Islam in the USA—which is still a subject of debate—this book plugs a certain gap. The author focuses chiefly on the proselytizing of the various strands of Islam—beginning in the 1920s—to disillusioned Afro-Americans, many of whom were incarcerated. One such was Malcom Little (who found fame and notoriety as Malcolm X), a hustler, pimp and burglar who joined the Nation of Islam while in prison.

For many incarcerated Afro Americans like Little, Islam offered religious and racial identities that fostered a new sense of self and more positive expressions of masculinity and femininity. Central to this is what Turner refers to as "Black Atlantic cool," a catch-all phrase that translates roughly into the fostering of an identity based on composure, social stability, intellectual acuity and physical and spiritual purification.

It's a term the author uses frequently, a reflection of its importance in understanding the alure of both Islam and jazz as bulwarks against systemic racism and the hypocrisy of Christianity, which came to be seen by increasing numbers of blacks as the religion of the slave owners, segregationists, lynch mobs and colonialists.

In charting the growth of Islam among beboppers, hardboppers and free-jazz musicians in Boston and New York, the author explains how the adoption of Islamic names (Yusef Lateef, né William Huddlestone; Ahmad Jamal, né Frederick Jones; Sahib Shihab, né Eddie Gregory, to name but a few) and culture was about taking back control of their personal and historical narratives.

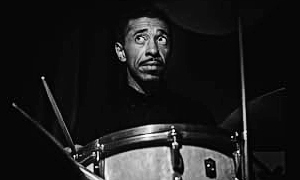

Art Blakey was one of those who questioned Christianity after a severe beating from Southern whites in 1943 that left him needing a steel plate inserted in his head. Blakey converted to Islam in 1947, saying: "Islam brought the black man what he was looking for, an escape like some found in drugs or drinking: a way of living and thinking he could choose in complete freedom. This is the reason we adopted this new religion in such numbers. It was for us, above all, a way of rebelling."

Whilst it is never really made clear just how many African Americans converted to Islam in the period covered by this book, the author identifies jazz musicians as being key players in its dissemination. Jazz musicians, effectively black cultural leaders, absorbed the rhythms and instrumentation brought by black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean, from Jamaica, Bermuda, Panama, Guyana, Trinidad, Montserrat and Cape Verde.

These new arrivals brought more than just their rhythms. Their anti-colonial politics and new religions contributed to a rising internationalism among African American blacks, who, fueled in turn by the powerful oratory of Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X, began to identify with pan-global black resistance to oppression and disenfranchisement.

Illuminating too, Turner's appraisal of the US State Department-sponsored jazz tours from the 1950s to the 1970. These tours, which sent leading jazz musicians all over the globe as part of America's anti-Communist, Cold War strategy, had the double-edged effect of raising Islamic African Americans' awareness of the international character of black religious and political identity. Such internationalism, the author posits, enabled Afro Americans "to construct powerful strategies against racial oppression in the United States."

In what was a perfect storm, the fifty-year-long Great Migration of blacks from the southern states—feeling racial discrimination and lynching—to the northern cities also fed in to the growing militancy and politicization of changing black identities.

It comes across as inevitable, in many ways, that jazz should reflect these seismic changes, and Turner is particularly good at tracing the religious markers in jazz in bebop, through hard bop and onto free-jazz. Just as many African Americans sought a reconnection to their ancestral roots by adopting African dress, hairstyles and Islamic names, so too jazz adopted new vocabularies that drew from African chants, call-and-response, elaborate rhythmic patterns and trance-like ecstatic highs.

Turner also examines the lives and careers of a number of prominent jazz musicians who converted to Islam. Though John Coltrane never officially converted to Islam, the author makes a strong case for the profound influence of Islam on him, and by extension, his music, particularly on his most iconic album, A Love Supreme (Impulse!, 1965).

Conversion to Islam, however, was no panacea. As Turner points out, Islamophobia was rife in the music industry. Nor could conversion to Islam save artists such as Grant Green, Lee Morgan or Etta James from their self-destructive heroin and cocaine habits.

In examining the links between African Americans, Islam, jazz and internationalism, Turner covers a lot of fertile ground. From the arrival of Muslim Ahmadiyya missionaries from India to the USA in the 1920s to the so-called Zoot Suit riots of 1943, from Malcom X to Cold War diplomacy and from Coltrane to free-jazz, Soundtrack to a Movement is a sweeping though incisive history that deserves a readership far beyond the confines of academic circles.

Tags

Book Review

Ian Patterson

NYU Press

Yusef Lateef

Ahmad Jamal

Sahib Shihab

Art Blakey

John Coltrane

Grant Green

Etta James

lee morgan

Malcolm X

Richard Brent Turner

Marcus Garvey

Zoot Suit Riot

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.