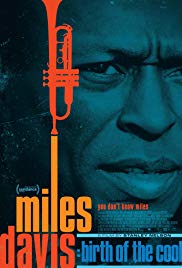

Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool

Miles Davis: Birth of the CoolFirelight Films

Director: Stanley Nelson

Run Time: 115 minutes

2019

In addition to his place as a legendary jazz musician, Miles Davis has long been a cultural hero for the African American community and for so many others of varied backgrounds and ethnicity around the world. We all continue to marvel at his creativity, personal independence, and passionate willingness to go to the wall to follow his muse, his instincts, and his heart. That is why, for example, the artist Barkley Hendricks chose "Birth of the Cool," the title of Davis' groundbreaking album (Capitol, 1957), for his powerful exhibition of life size portraits of contemporary African Americans at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, thereby acknowledging Davis as an enduring cultural symbol.

Similarly, film director Stanley Nelson chose "Birth of the Cool" as the subtitle of his mammoth documentary of Miles Davis' life and music which premiered at the Sundance Festival this year and is now being released in theaters, DVDs, and eventually a television mini-series. The actual Birth of the Cool album occupies only a few short minutes in an epic portrayal of Davis the man and his music that spans his entire life cycle. Such a phrase, though, highlights the prevailing view of Miles Davis as the personification of "cool." Yet there was so much more to him than his cool persona. This comprehensive and soul-searching documentary shows that underneath the façade of his hip attire, sunglasses, the Ferrari, romantic affairs, prize fighting interest, and musical inventiveness, there was a raging fire of creation and destruction that fueled his music and love life, and that contributed to the drug and alcohol addictions that cost him untold darkness and pain. This film pulls no punches about the troubled, wounded, and angry side of Davis. We see him at his best and worst, rising and falling.

The film is a searing documentary that goes beyond testimonials, sounds, and pictures to provide a breathtaking study of Miles Davis as an astounding creative force and a "hero with a thousand faces." The story is aptly narrated by actor Carl Lumbly in Davis' persona and raspy voice, entirely in Davis' own words from his autobiography (Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe: Miles, Simon and Schuster, 1979) and the audio tapes that Davis made for the purpose. The film contains numerous commentaries by musicians, scholars, critics, and business cohorts and others who knew Davis well through friendship, love relationships, band membership, and/or scholarship. Included among them are drummer Jimmy Cobb, Santana, Quincy Jones, critic Dan Morgenstern, impressario George Wein, bassist Ron Carter, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, pianist Herbie Hancock, ex-wife and dancer Frances Taylor, his offspring, and a host of others whose attitudes range from detached objectivity to profound empathy and grief in their portrayals of him. There is a steady flow of his music, video and film clips, family photographs, and flashes from key events and places that keeps the film moving forward at a relentless pace. The film goes far beyond virtually any other documentary or biopic of a jazz musician in its depth and detail. On the one hand, that complexity and comprehensiveness is very gratifying. On the other, it frustratingly lacks opportunities to stay with particular music and events for longer durations. This is true especially of the music, of which the clips are much too short to fully appreciate their significance. However, that would seem inevitable in covering Davis' entire life span.

There are two essential binding dynamics that this film brings to the fore about Miles Davis: 1) that the trajectory of his life and music was integrally related to the changing historical and cultural context; and 2) that he was a very complex musician and human being on an almost larger-than-life scale, a tragic hero who belied the conventional images of him as either a cool hipster, a genius who mingled with the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre and James Baldwin, or an antisocial isolationist who was dismissive of anyone he didn't like. We see these various sides of him, but the film leaves no doubt that there is something more there that defies explanation. Along with its probing insights, the film suggests remaining mysteries about Davis' inner workings that can't be documented. That is not a shortcoming of the film; it is rather that it is almost impossible to really get inside a man like him. There was an X-factor that he kept hidden from view and that maybe he himself didn't know about.

Regarding the historical and cultural context, here was a proud man, who from the beginning was exposed to psychological trauma (his parent's failed and abusive marriage) and the oppressive segregationist nature of the times. He knew racist bullying and exclusion as a child. But the later scenario in which he was brutalized by an NYPD cop for insisting on his right to take a cigarette break underneath the canopy of Birdland with his name on the marquee is devastating and makes one wonder how anyone could ever recover from mistreatment like that. Photos from the episode graphically show the horror and injustice involved, a bleeding and bandaged Davis being rudely processed as a "criminal" at the police station. Segregation and the "race card" haunted, damaged, and propelled Davis throughout his life. (He couldn't or wouldn't find an inner haven from it like Louis Armstrong and John Coltrane, both outspoken about it but able to find inner peace.)

On the other hand, the post-World War II flourishing of existentialism and jazz music proved fertile ground for Davis to come of age. His acceptance and veneration in Paris, his jamming and mingling with the jazz greats like Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker in Billy Eckstine's band and on 52nd Street in New York, hence his presence at the birth of modern jazz, and his exposure to post-war life with its sports cars, materialism, and stereotyped romantic relationships all influenced Davis, and his music became both a reflection of and antidote to them. Later, his identification with both African American and hippie culture led him towards music that had psychedelic, rock, rap, and hip-hop qualities, so much so that icons of these genres prized his contributions. The film brings out the paradox in Davis, that he was someone who went his own way and yet he was an active participant in everything that was happening around him.

The second crucial aspect of Davis that comes through in the film is that, to paraphrase a Judaic saying about God, "Just when you think you know who Miles Davis is, that's what he isn't!" Because of the visual images, testimony, and music it contains, the film shows even more than his candid autobiography what a complex and undecipherable figure he was. Here is where the "birth" motif is important. We see and feel how Davis is re-born over and over again, a theme which is crucial to his very being-in-the-world. The transformations are almost too frequent and mysterious to comprehend. One day he is a music student at Juilliard. He drops out to become part of the bebop-hard bop jazz scene. Suddenly, he develops a unique muted trumpet sound that is like his soul talking. He forms a noted band that brings out the genius in John Coltrane and in which their very different approaches blend perfectly. Soon he is co-inventing a whole new approach to big band music with Gil Evans with himself as soloist. On the heels of that smashing success, he recruits a small ensemble of cutting edge musicians and walks into Columbia's studios with a concept of modal music in Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959) that changed the face of jazz. As if that weren't enough, he establishes the extraordinary band with Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Wayne Shorter, and Tony Williams that explored new territories of harmony, rhythm, and co-improvisation. And then he goes beyond even them to new bands taking in rock, funk, fusion, and other genres. With each transformation in the music, there is also a change in his appearance, attire, love relationships, and peer groups, as if he is creating a new version of himself.

We can only speculate what was going on deep inside Miles Davis' heart and mind as he re-invented himself. What emotions and mental complexes impelled the changes that occurred? Certainly, he had a strong desire to prove over and over that he could conquer racial prejudice as well as his inner demons. Behind this conquistador striving for success and renewal, there was enduring rage that came from his father's abuse of his mother and the police incident at Birdland. Whether he suffered in addition from post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and/or bipolar disorder is something that psychiatrists can speculate about. His aggressive drive and libido were very strong and insatiable. He was so passionate about love that its intensity overwhelmed his lovers like Frances Taylor and Cecily Tyson (who is barely mentioned in the film). But the real miracle lies in his ability to tame and transform these seething emotions into one musical innovation after another, through an incredible musical ear that heard not only the notes but all the possibilities they carry in terms of emotion, concepts, ensemble playing, and story telling. Even Freud said that such artistic genius defies explanation.

What ultimately comes out of this film is that Miles Davis can truly be understood only in broad and all-encompassing mythological terms. The myth of Orpheus, the musician, poet, and prophet who was possessed by the underworld through an irresistible backward glance at his lover, Eurydice, comes immediately to mind. The ups and downs of love drove Davis to distraction and possibly addiction, his own underworld. But that love was probably also responsible for his musical and personal re-births and self-transformations. As the film shows, his love was reciprocated by his friends who grieved for his tragic denouements. For some reason, no mention is made of Gil Evans' caring visits to Davis twenty years after their collaboration, during the latter's addictive social isolation, and Evans naming his son after him. But you can feel the warmth and empathy for Davis in the testimonies of those who got to know him closely, even those hurt by him. And regarding his anger, it would require a playwright like Eugene O'Neill to capture the depths of it in plays like The Emperor Jones and The Great God Brown, the latter dramatizing the interplay of the inner self and social masks, curiously first performed in 1926, the year of Miles Davis' birth.

Critics will have varied opinions of this film, depending on what they focus upon. Yes, it is too much of a collage of what seems like everything director Nelson could get a hold of. Yes, some of the testimonials, particularly by those who did not know him personally, seem sycophantic or scholarly rubbish. Yes, it is a bit disorganized at times, as when the film flashes irrelevantly back to the end of WWII (1945) after covering the Birth of the Cool album (recorded 1950, released 1957). But like Davis himself said, no note is a bad note. It depends what you do with it. This film deserves accolades for the way that it pursues the deeper truth of a jazz musician's life, times, and music. In that respect, it thankfully derails the stereotypes of these creative artists who brilliantly conceived and re-conceived what Billy Taylor—or some think Duke Ellington or James Baldwin—called "America's classical music" and who are too often portrayed in a superficial light. The film leaves no doubt that Miles Davis was not only an awe-inspiring jazz musician, but one of the great creative artists of the twentieth century and a tragic hero who achieved the heights at the cost of experiencing the heart of darkness.

Tags

Film Reviews

Miles Davis

Victor L. Schermer

Jimmy Cobb

Quincy Jones

Ron Carter

Wayne Shorter

Herbie Hancock

Louis Armstrong

John Coltrane

Gil Evans

Tony Williams

Billy Tayor

Birth Of The Cool

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.