Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Jack Pyle's Son

Jack Pyle's Son

In Philadelphia the (Big Band radio) guy was named John Thomas Pyle, but to absolutely everyone, he was simply Jack. Jack Pyle.

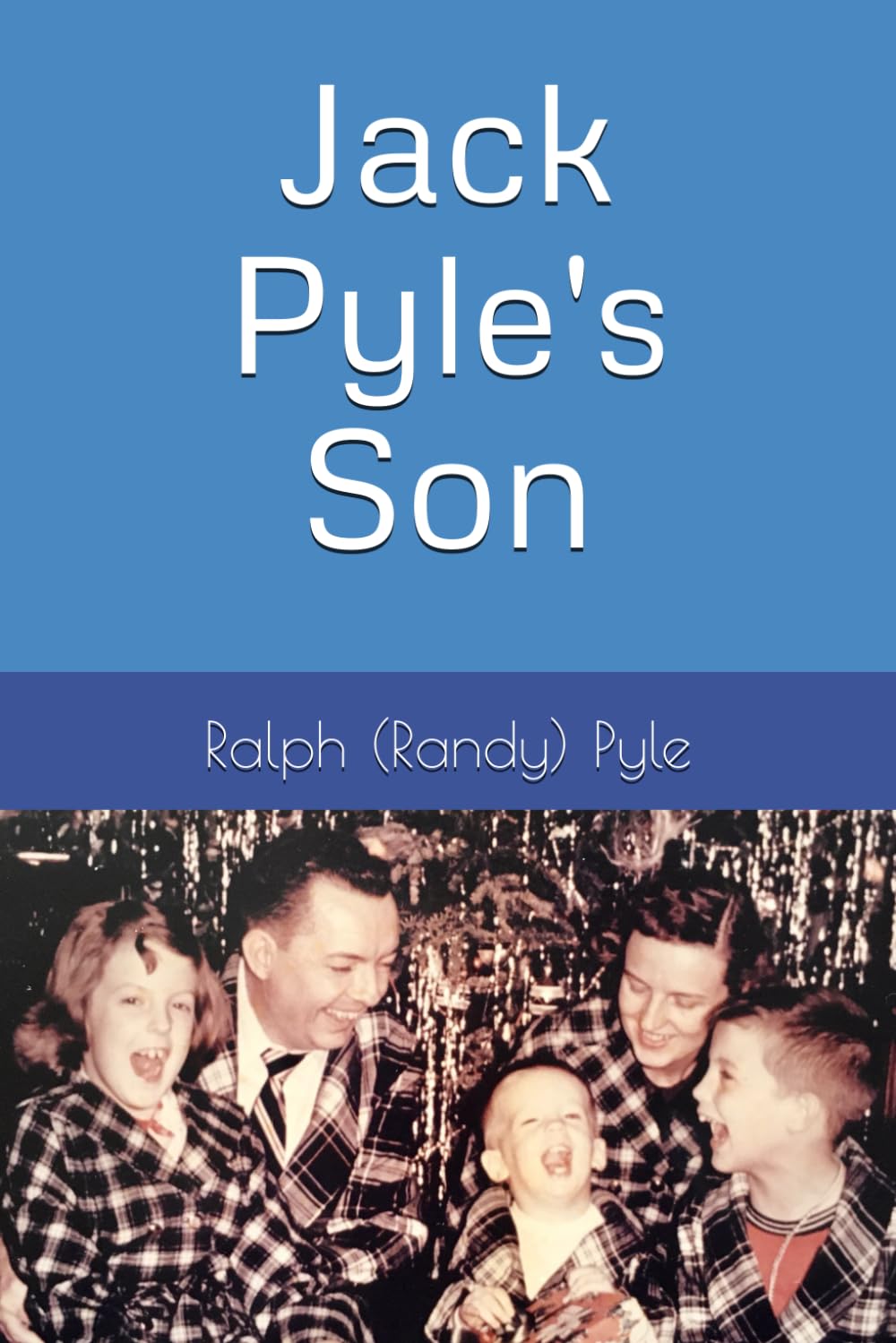

Jack Pyle's Son

Jack Pyle's Son Ralph (Randy) Pyle

254 Pages

ISBN: # 13:9798326940865

Ralph Pyle publisher

2024

One must be of a certain age to remember when life in an automobile was inevitably accompanied by AM radio. You must be even older (and probably a centenarian) to remember when the home radio was the center of family life and television still an experimental concept. Some would imagine not pre-digital, but prehistoric, with some sort of Flintstones-like device as the receiver. Well, not quite that ancient. Boomers had their own imagined communities in all the big cities, with names like WABC, WFIL, or KRLA, top forty stations that played commercial rock. Every station had one or more totemic figures, some version of what was called a "boss jock," a guy (inevitably) who was a local, regional, or maybe even a national celebrity. Those were the days, my friend, we thought they'd never end. But they did. By the early 1980s, radioland was no longer the same. Today, it may be a matter of some good fortune whether or not a vehicle even includes an AM radio. Or if it does, whether the driver tunes in.

Philadelphia, PA, was like every other big city. There were radio voices that were instantly recognizable, as much a brand as any hot dog or beer, and thus of corresponding value. By virtue of the postwar Baby Boom, most did some flavor of rock and roll if music was on offer. As they said in the business, Boomers were the "demographic" that mattered, an audience of people mostly born between 1946 to 1964. They were the target audience, the large one that advertisers coveted. And the stations made the DJs stars.

Yet, somehow, there were always a few holdouts, personalities from an earlier era who appealed to a mostly older audience, people to whom we now refer as "The Greatest Generation," or "The Silent Generation." They had lived through (at least) the Great Depression and World War II. Those experiences were formative, and for most, their music came from the days when jazz and swing had been popular music. If they retained a residual emotional connection to the music of their youth, it was more likely associated with Benny Goodman or Artie Shaw or Duke Ellington or Count Basie. The Beatles and the The Rolling Stones were definitely an acquired taste. Boomers notwithstanding, the elders maintained a few niche stations and supported "radio personalities" who catered to their market. In Philadelphia, the guy was named John Thomas Pyle, but to absolutely everyone, he was simply Jack. Jack Pyle. There were a few others, including Joe McAuley, whose granddaughter is actress Anne Hathaway. But Jack was The Man.

Pyle was, as they used to say, a character. One of his friends, another radio guy, described Pyle as usually "looking like an unmade bed." It is virtually impossible to describe exactly what it was that made Jack Pyle so special, other than playing big band music, kibitzing on the air, and doing a fair imitation of Johnny Carson's borderline breakup, but radio-style, and very much his own. Yet, in the final analysis, Pyle was a Swing Band aficionado, and if that is what you wanted to hear, well, you followed Jack around the airwaves (or "The Dial" as they said in those analog days). And one way or another, you remembered your 1930s youth or, if born in the 1950s, got to learn why Benny Goodman's 1937 trumpet section was, as Duke Ellington put it, "a wonder." Even if Goodman's heyday had taken place long before you were born. A Boomer who wanted Swing 101, got it from Jack Pyle.

Ralph (Randy) Pyle is Jack's youngest child and has written a biography and a memoir. As far as music and the history of Swing on radio is concerned, the first half of the book—which coincides with Jack's all too brief 46-year life—will be of most interest, although Randy's experience as a freelance musician while holding down a variety of day jobs is apt to find a sympathetic audience as well.

Jack Pyle came from a relatively well-off family but was a version of Peck's bad boy who got into radio almost in a fit of absence of mind. As a teenager, Sonny Dunham tried to recruit Jack as a band boy, but the job fell through. Pyle grew up idolizing people like Bunny Berigan, whom he saw in person and never forgot. After an extended gig in the Coast Guard, Pyle casually walked into a radio station in Norfolk, VA. He said, more or less, I can do as well as anyone you have on the air. Well, Pyle knew how to pitch himself, because he got a job, and after that, slots in Nashville and Cincinnati. In 1950, he went to Philadelphia, where he became a fixture and a local celebrity, until his death in 1966.

Depending on when a reader came into the story, Pyle became what is called a "Broadcast Pioneer" in Philly. He did some early television (including the weather), but his principal gig was as a morning man on major stations like KYW and WRCV. If you were up at 6AM in the early 1960s, Pyle came on to the strains of Glenn Miller's "Slumber Song," and he could be counted on to get the day rolling, ready or not. He had something of a folksy style, not completely alien to the market there then, and whatever you got, you knew you would hear "good" music. He did not play top forty, and you might be surprised by hearing Ella Fitzgerald so early in the day, but that was Pyle. Randy speculates he could have gone farther in Philly radio had he bowed to commercial pressure, but that was not Jack. He would sooner lose a job than play crap and sometimes he did lose the job. For a while, he moved to WCAM in Camden, NJ, where he had an afternoon show. The hour may have changed, but the music never did. Pyle was in close touch with the scene in Philadelphia and was a famous habitué of Billy Krechmer's club on Ranstead Street. He promoted Krechmer. Krechmer returned the favor, recording a Dixieland tune called "Pyle of Jack." It is still fun to listen to.

Probably the peak of his career was when Pyle ended up doing a broadcast on WPBS-FM, of all places (PBS meant The Philadelphia Bulletin Station in the 1960s), first in the morning, and then for four hours on Saturday nights, something he called "The Big Bandwagon" which featured a variety of bands, and always an hour of Glenn Miller "until Midnight." Pyle did several things. He talked about the music in his own inimitable way. And he reconnected a lot of people with an earlier time in their lives. He also told jokes, sold a local beer, and made occasionally rueful comments on the state of music and the world. If a listener was too young to have been there for Harry James or Artie Shaw, well, this was an opportunity to learn from someone who had been there. Needless to say, Pyle attracted a substantial following. And then he was suddenly gone. Not canned, but dead.

Randy Pyle is nothing, if not brutally honest, about the toll that Pyle's career took on his family, and ultimately, on his health as well. He died of congestive heart failure in 1966 at the terribly young age of 46, and one senses that this book is Randy Pyle's attempt to finally come to terms with the effect that Jack's life and death had on him. Randy Pyle does not prettify or airbrush anything, including the personal consequences of being the child of someone deeply involved in the music business. His honesty makes his account all the more compelling, because one way or another, the world of the AM radio on which Jack Pyle made his public life is now gone for good. That world, like Jack's beloved swing bands, are not coming back. This may be one of the few ways to still access it. Randy has also posted an edited version of a 1966 tribute broadcast on WPBS to Jack Pyle on You Tube (see below). It is well worth listening to as a supplement to the book as well. Jack lived an interesting life. And Randy, probably because of Jack, has in his own way too. The music business is many things, but glamorous in its everyday reality is not one of them.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.