Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life in Music

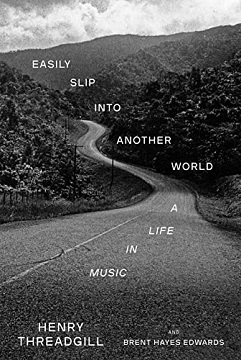

Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life in Music

Maybe it should be my epitaph: 'Henry Threadgill: Failure is Everything.' I don’t mean to be fatalistic—it’s simply a fact. Failure is the greatest motivator of all.

—Henry Threadgill

Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life In Music

Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life In MusicHenry Threadgill and Brent Hayes Edwards

403 pages

ISBN: #9781524749071

Alfred A. Knopf

2023

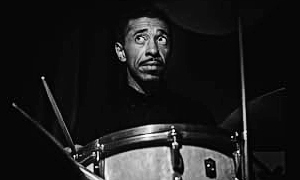

In the early 1970s, Henry Threadgill—composer, multi-instrumentalist, bandleader, inventor of the hubkaphone, Vietnam veteran, and all-around Proteus (in Ovid, the god "who always changes") of Black music and culture— encountered Yusef Lateef backstage and approached him for some advice on switching between wind and reed instruments. The elder musician's answer wasn't encouraging: "Lateef met my gaze without flinching. 'I think you'll just have to keep working on it.' And that was that." The conclusion Threadgill draws from this meeting hints at a way to read his autobiography: "The tradition gets passed down that way, too: in the blank spots, in recalcitrance or refusal, in what goes unsaid." Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life in Music teems with "blank spots": the resonant silences and unexpected swerves that make Threadgill's compositions—for ensembles that include Air, X-75, The Henry Threadgill Sextett, the Windstring Ensemble, Very Very Circus, the Society Situation Dance Band, the 14 or 15 Kestra: Agg, and Zooid— unmistakable.

Threadgill repurposes the title Easily Slip Into Another World from his Sextett's 1988 album, but many of his titles also challenge literal-minded listeners, with a characteristically cryptic humor, to "keep working on it": "Keep Right On Playing Thru The Mirror Over The Water," "Salute To The Enema Bandit," "Through a Keyhole Darkly," "Black Hands Bejewelled," and "Dangerously Slippy," for a start. Starting with their titles, Threadgill preserves his compositions' mystery: "I find that the less I say about my music, the better. If I say anything, it tends to be oblique or oracular: words meant to jar the listener out of the complacency of expectation." With his collaborator Brent Hayes Edwards (who moonlights as the Peng Family Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University), Threadgill concocts a "slippy" raconteur-theoretician-trickster narrative voice that combines Black oral tradition's feints and shades of intonation with the wordplay and allusiveness of a literary text.

In Epistrophies: Jazz and the Literary Imagination (Harvard University Press 2017), Edwards interrogates "the ways musicians themselves talk and write about their art." His collaboration with Threadgill captures the particular cadences with which the latter talks-and-writes about his art. Readers can cull their own mini-anthologies of favorite "oblique [and] oracular" passages from Easily Slip Into Another World. A few instantly recognizable Threadgill-ian utterances include:

My invisibility experiments came to an abrupt conclusion after my mother took me to a party at someone's house and I got caught trying to make a baby disappear.

Sometimes I have to destroy my own process to get to something new.

When you're an artist, you've got to be careful in your training. Practice doesn't make perfect; practice makes permanent. When you start putting things in yourself, it's going to take time to get them out. You might need a big aesthetic enema.

Maybe it should be my epitaph: "Henry Threadgill: Failure is Everything." I don't mean to be fatalistic—it's simply a fact. Failure is the greatest motivator of all.

Shooting a big gun for the first time is like trying to dance with a woman you've just met. It's a physical embrace. And guns have a rhythm. You have to intuit the way the gun wants to move in order to gain control over it. You get it wrong, you're going to be stepping on each other's toes all night.

For some of us it takes a road-to-Damascus moment to appreciate the aesthetic qualities of the everyday industrial objects that surround us.

Although Edwards's Epistrophies contains a chapter that illuminates "Henry Threadgill and the Micropoetics of the Song Title," his collaboration with Threadgill preserves the laconic mystery of the latter's titles and, more broadly, of his utterances on (for a start) rhythm, failure, music education, military weaponry, invisibility, experimentation, and hubcaps. Whatever form their collaboration took behind the scenes, the resulting book invites readers to have a leisurely, intimate, uproarious, deadly serious, and at times constructively enigmatical conversation with one of our most wily and brilliant thinkers-about-thinking-about music (in the broadest possible sense) today.

Threadgill repeatedly frustrates readers' expectations about his musical influences per se. His fleeting backstage (and phone booth!) encounters with such jazz giants as Lateef, John Coltrane, and Duke Ellington read as comic, absurdist mini-dramas. (By describing his appearance in background of a long-lost photograph of "General William C. Westmoreland in Dak To at the end of November 1967" as "the invisible man at the center of the action," he tips his hat to literary forbear Ralph Ellison.) Instead, he often invokes the "presence" of family elders, who return the favor by sidling into Easily Slip Into Another World at key moments and subverting the book's ostensibly chronological structure. A chapter mostly devoted to Threadgill's 1980s-era Sextett pays an impromptu homage to his Grandpa Pierce, whose "spirit of radical experimentation" extended to medicine: "He had the usual folk remedies—castor oil, bitter apple, ginger, comfrey root, goldenseal, elm bark—but he had a stash of all sorts of other stuff. He would invent his own concoctions." Grandpa Pierce becomes a key touchstone for Threadgill's lifelong "resourcefulness—that impulse to tinker with an art that is provisional, always in the process of finding its form."

With its focus on Threadgill's first four-and-a-half decades, Easily Slip Into Another World tells a particular story of "finding [a] form": a portrait of the artist as young Black man, composer, musician, student (in various formal and informal contexts), world-traveler, and father. At the same time, he repeatedly locates his formative years—a term he might reject as too conventional—in a larger musical-historical context: "If you look at a book on the history of Western classical music, there's centuries of background you can read about. Black music in America is relatively young. It's still just the beginning." Threadgill doesn't cross paths with drummer Steve McCall and bassist Fred Hopkins, with whom he'd form the seminal trio Air in the early 1970s, until two-thirds of the way through the book. Instead, he dives deep into his development throughout the 1950s and 1960s:

Up through my generation, we all followed the same path. Despite all the incidental differences of individual experience, we all took the same route to becoming musicians in the Black tradition. You start playing an instrument. You start having musical experiences—not just sitting in a classroom playing scales or practicing in student ensembles, but instead out in the world: in little bands you put together with your friends, in churches and funerals and parades, at parties, at school dances, wherever. This is laying the groundwork. And it needs to go on for a significant period of time in your life. It might seem haphazard or juvenile, but it's extremely important in terms of your development as a musician.

Even if one limits Threadgill's generation to musicians born, like him, in the first half of the 1940s, and who appear in Easily Slip Into Another World's engrossingly comprehensive index—a cohort that includes Lester Bowie, Wadada Leo Smith, Olu Dara, Jack DeJohnette, Oliver Lake, Amina Claudine Myers, and Anthony Braxton—the list brims with trailblazers, many associated with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. You'll have look elsewhere for the story of AACM's founding in 1965, however, because at the time, Threadgill was often on the road, playing in the ensemble of Horace Sheppard, "the traveling evangelical preacher" who electrified his audiences: "Sometimes it was almost like James Brown: he would come flying out from behind the pulpit down right in front of the pews and land doing the splits—right in the middle of the sermon!"

One of Threadgill's key "musical experiences" occurs in 1965, when he served "as a de facto music director" at the Langley Church of God, where, as "at other churches in Chicago, you'd see some of the same faces playing in a church Sunday morning that you might have seen playing in a nightclub Saturday night." After Threadgill's tenor solo on "His Eye Is on the Sparrow" gets "hardly any reaction at all" from the congregation, Langley's Reverend Morris pulls out a disused alto saxophone from "under the pulpit," asks "Henry" to have the alto repaired, and then play the same hymn on it the following week. Threadgill characterizes the result as "something momentous":

I played "His Eye Is on the Sparrow" again, this time on alto. And this time, the response was completely different. The congregation was buzzing: you know it's going well when people start commenting while you're playing. Not just a few half-hearted notes of assent, but unrestrained interjections of spontaneous approval. A rippling cascade of Amens as I reached the bridge. And outbursts of commentary as I got farther into my solo. "Play your instrument, young man!"

More than twenty-five years later, no longer a "young man," Threadgill and his ensemble Very Very Circus play for an even more inspired audience on the beach of "Goa, [a] small state on the southwestern coast" of India, where he would ultimately make a part-time home with his then-future wife Senti:

People stood up and were dancing in the aisles—not just a couple of free spirits, but what looked like a majority of the crowd. Some were running up to the edge of the bandstand and spinning around in circles or falling on the ground like they were catching the spirit. I suppose the only way to describe it is to say that they were catching the spirit. I'd seen congregants transported to the point of possession and speaking in tongues in evangelical churches in Chicago, and I'd seen my share of frenzied thrashing and slam dancing in the punk scene in New York. But I'd never seen one of my ensembles provoke quite this degree of collective delirium.

Easily Slip Into Another World teems with accounts of unanticipated, preternatural performances like these, documented nowhere else but in Threadgill's words.

Recorded music turns out to be the tip of a very, very deep iceberg in Threadgill's Life in Music. "I don't think of my discography as the central documentation of my contribution as a composer," he declares. You won't find the one of his most electrifying ensembles, the Society Situation Dance Band, on that discography at all because "the decision not to document it on record was entirely deliberate." (Fortunately, an excellent, hour-long video recording of this ensemble's 1988 performance at the NDR Jazzfestival Hamburg is available on YouTube.) He contrasts the "laboratory atmosphere of a recording studio" with the "mysterious exchange that happens with a specific group of listeners who happen to be there for that set on that particular night."

This "mysterious exchange" can have dire consequences, as is does in the summer of 1967, when, as head arranger for the Post Band at "Fort Riley outside of Junction City, Kansas," Threadgill incorporates the "angularity and dissonance" of Thelonious Monk and Stravinsky into "a medley of great American national songs." When the Post Band starts playing his medley for an audience of military, political, and religious VIPs—without having rehearsed it—one highly-placed listener interrupts:

We launched into the arrangement and didn't get more than eight bars into it before the Catholic archbishop stood up and yelled at us: "Blasphemy!" He was furious. The pristine white and crimson of his chasuble and his ornate pointy miter only made his outburst all the more shocking. "This is an outrage!" he thundered. "Pure blasphemy!" The conductor, unsure what to do, signaled to the band to stop.

The whole episode echoes farcical depictions of powerful establishment figures in mid-twentieth century literature, from Joseph Heller's Catch-22 to Paul Goodman's Growing Up Absurd to Ellison's Invisible Man; but this irate, flesh-and-blood archbishop's authority is all too real. The "eight bars" of that aborted concert have decisive consequences for Private Threadgill just a few days later: "I'm on my way back to Chicago for thirty days to arrange my affairs before I'm deployed to Vietnam."

Threadgill braids his personal history as a musician and as a soldier together most disquietingly in an account of another interrupted performance—this one in the Central Highlands of Vietnam with the 4th Infantry Band, whose members defy a substitute conductor's orders not to take their weapons onstage:

The conductor was miffed. We stared him down. There was nothing to do but start playing. He gave a downbeat and we launched into a tune. We didn't get more than four bars in when all hell broke loose. A small contingent of Vietcong ambushed us right as we started playing! Easy pickings, they must have figured. We immediately dropped to the ground and returned fire, while we watched the conductor scramble to find cover as the bullets whizzed around him. He was scared to death. I remember looking at his silly ass, thinking, "Yeah, where's your gun now?"

Threadgill writes about combat in Vietnam with the same immediacy and verve that he relates, say, his short stint with the Cecil Taylor Unit decades later. At times, the diction even overlaps: in Vietnam, he faces the "pressures of living constantly with mortal risk in a bewildering and alien environment"; while he finds Taylor's method of dictating a series of notes to each player "a bit bewildering." That qualification—"a bit"—reveals the limits of comparing combat in Vietnam to an avant-garde jazz rehearsal. But Threadgill's as scrupulous a writer as he is a composer, and the faint echo set up by "bewildering" invites us to slip between the worlds of Pleiku in 1967 and Chambers Street in 1980, if only for a moment.

Like many veterans' accounts of Vietnam, Threadgill's narrative encompasses "the experience of the aftermath—the trauma of coming home, on top of the trauma of the war." He remembers: "Vietnam stayed with me, and it took me to some dark and twisted places even once I returned to Chicago." Those "dark...places" haunt Easily Slip Into Another World's more-or-less linear structure, as in a memory of Threadgill's seventh grade teacher in the first chapter:

Mr. Zimmerman would tell the kids to put their heads down and rest, and he would go and stand at the window and stare out the window as if he were remembering something. I think he was a veteran, maybe from the Korean War. There was something about him. After becoming a veteran myself I can kind of spot certain things in people, especially people that have been in war zones. I can't tell from people who've never been in a war zone—they don't have any of the little signature kinds of things I can pick up on—but with people that have been in those kinds of dynamic situations, there are telltale signs.

Threadgill refuses to reduce his perceptual keenness solely to "the trauma of the war":

You acquire a heightened sensitivity to sound. Your body learns quickly that listening can be a matter of life or death. Your ears start to pick up things you wouldn't even have noticed back at home, because in the war missing the slightest signal at the wrong moment could get you killed. Your body learns to hear things with great precision even while you're asleep, and to jolt you awake at any hint of a threat. For any artist, such a profound transformation of your understanding and perception can't help finding its way into what you're doing.

In passages like these, Threadgill's Vietnam experience moves beyond the boundaries of the two chapters devoted to his military service and loops backward into his childhood and forward into his subsequent musical development.

His post-Vietnam "heightened sensitivity to sound" leads to an epiphany about the musical properties of hubcaps, and ultimately to his invention of the hubkaphone, a musical-kinesthetic instrument he would play from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s:

I spent hours testing out various hubcaps, noting down their pitches and designing modes. Many of the caps had more than one pitch, just like a drumhead or a cymbal: you'd get one pitch if you struck the edge and others if you struck a ridge, or the knob in the middle. I didn't worry about trying to follow scales or classical modes. The whole point of inventing a metallophone wasn't to replicate the Lydian mode. Instead I made up my own combinations of pitches.

Easily Slip Into Another World invites readers to participate in this and many other acts of invention by not letting us off the hook. You can't read Threadgill's autobiography passively, waiting for answers and easy explanations. This Life in Music, he asserts, is "not a listening guide. If anything, it is an extended defiance of that expectation. If it's meant to teach you anything about my music, it starts with the lesson that you need to relinquish that desire for transparency. Music is about listening." By teaching us to listen to his voice on the page, and beyond it, Threadgill creates a sui generis aural text that widens the scope of "musical experiences" for the twenty-first century—and arrives at a multitude of answers to his mother Lillian Threadgill's question: "Henry, why do you always have to take the most radical option?"

Tags

Book Review

Henry Threadgill

Eric Gudas

Yusef Lateef

Henry Threadgill Sextett

John Coltrane

duke ellington

Fred Hopkins

Lester Bowie

Wadada Leo Smith

Olu Dara

Jack DeJohnette

Oliver Lake

Amina Claudine Myers

anthony braxton

James Brown

Sonny Rollins

Gene Ammons

Thelonious Monk

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.