Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » The Sound I Saw

The Sound I Saw

The Sound I Saw

The Sound I Saw Roy DeCarava

208 pages

ISBN: # 13: 978-1644230107

David Zwirner Books

2019

When two or more art forms combine, they may serve and harmonize and support each other or they may clash. The sound I saw combines felicitously three art forms: jazz, photography, and poetry. It is a large (10.25 x 1.2 x 13.25 inches), heavy (five pounds), and majestic book of black and white photographs, augmented by sparse but sparkling poetry by the brilliant (if not fully appreciated) African American photographer, Roy DeCarava (1919-2009). DeCarava directed his visual medium into the sonic space of jazz and its environs to capture the spirit of its sound in silent but annotated image. The work was originally created by DeCarava in the early 1960s as a kind of maquette or prototype and kept in an old suitcase. Although rumors abounded and bits were published, it was not formally released until 2001. This new edition features two illuminating essays—one by art historian Sherry Turner DeCarava, his long-time collaborator and widow, and another by filmmaker, Radiclani Clytus. We will focus on the DeCarava's text.

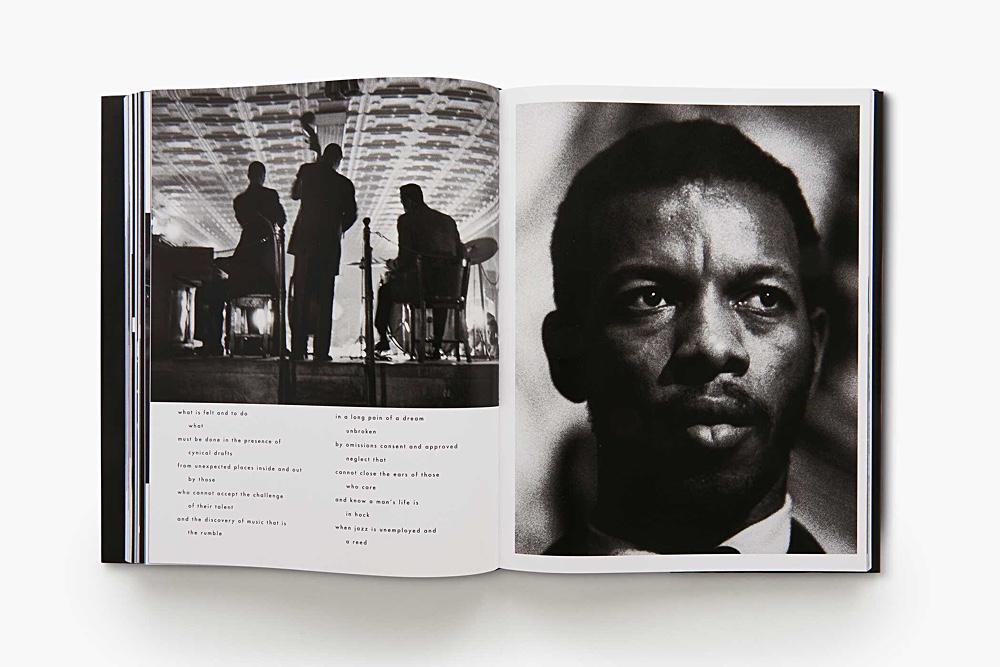

DeCarava previously collaborated with black poet Langston Hughes (1902-1967) on The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955; republished 2018), which described in Hughes's prose narrative and DeCarava's images everyday life in his native Harlem through the voice of a black grandmother reflecting on her life, her family, and her neighborhood. In the case of the sound I Saw, DeCarava supplies both text and image. The words form a lyrical expression of the city's music. The poetry represents a weaving, itself—reflective narratival journalism, even a shade of existential mysticism with its stream-of-consciousness format, punctuated with double entendres.

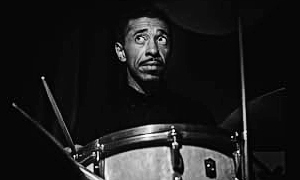

Given its arresting images and words, the book itself calls for some philosophical reflection on the nature of the image and the art of photography. It is not a typical coffee table book that you page through when not otherwise occupied. It inspires contemplation and repeated viewing/reading. And you do not want to spill coffee—or anything else—on it. We cannot see music, as we can see landscapes and artists. The book's title is odd and enticing, given its synesthesia: the sound I saw. How can you see a sound? Photographing musicians, sans music is, on that score, already a bit daunting. That which is most significant about the musician qua musician cannot possibly be captured in a sonic desert. The photograph is frozen in time. Music requires time to be music at all. The photograph cannot speak or sing or solo, but it does show. It may show someone singing or playing the saxophone, the trumpet, the bass, the drums. The soundtrack, however, must be found elsewhere—if it can be found anywhere.

Roy DeCarava saw the sound of jazz in the scenes of the city of New York. He writes, "This is a book about people, about jazz, and about things. The work between its covers tries to present images for the head and for the heart and, like its subject matter, is particular, subjective, and individual." The virtuoso jazz photographer must relish the music and musicians that he labors to capture in an image. Aesthetic veneration is needed. We apprehend that love in Herman Leonard's black and white "jazz portraits" and we see it in the sound I saw as well.

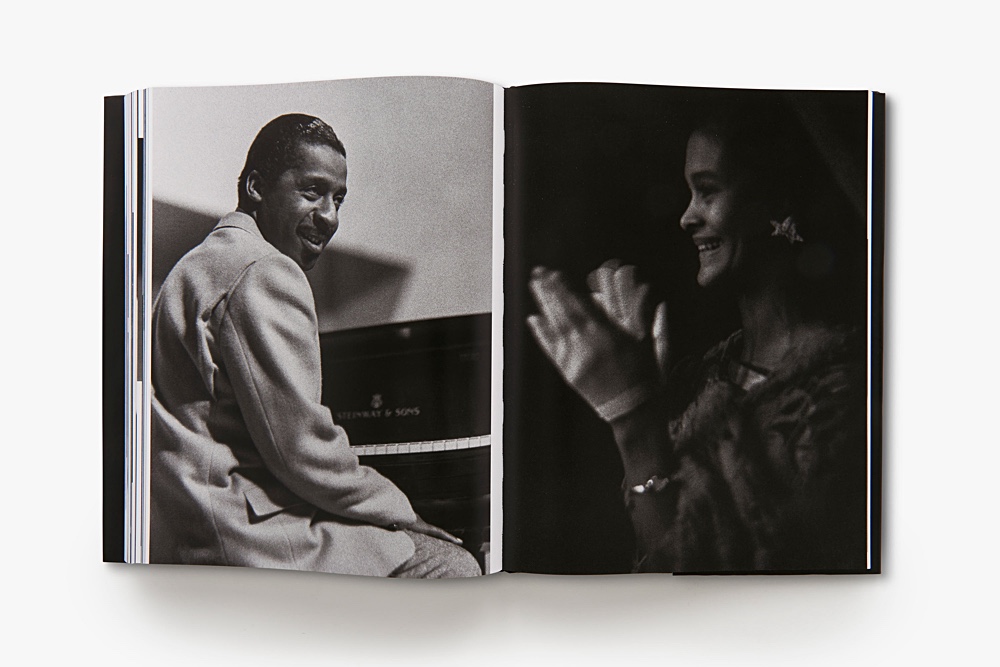

DeCarava displays not only images of the musicians and their audiences, but also of the inner cityscapes that shaped the jazz soundscapes. Much of the exterior of New York City in that day was caste in black and white, so that medium finds its home there. However, DeCarava's skillful use of silver gelatin prints transcends the prosaic description of "black and white photography," in light of the rich and varied palate of shadings of his work. I had never seen a noncolored photograph sparkle before seeing this collection. He loved to work in shades of gray.

Besides the photographs of musicians on and off stage, we see children playing on gritty streets, starkly functional apartment buildings, a black man lying on the sidewalk. It can be bleak, but none of the musicians look the part; they transcend the often cramped, dark environs. What's disconcerting about it all is the sustained tension: shattered windows and piles of fallen, crumbled bricks up against shiny brass horns and sweat-drenched musicians, blissed and transcendent; images with sharp emotional edges up against fuzzy images shrouded in shadows; and high-class clubs and lower-class citizens.

None of the photographs are titled. DeCarava probably assumed that his audience would recognize the more well-known musicians, such as Coleman Hawkins, Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and Count Basie. I was able to also identify Ornette Coleman, Elvin Jones, Horace Silver, Lester Young, Mary Lou Williams, and Kenny Burrell. Several of these musicians appear more than once. Even as an avid student of jazz, I could not pick out every musician by name. The photographs of nondescript people and places speak for themselves.

One wonders if the blurry pictures are out of focus...or animated. Jazz can move fast, shape-shifting its venue. Did DeCarava fail to keep up, or capture the brilliance of the passion? He displays a knack for visual easter eggs, and this provides a clue to reading his poetry. Several stills have a picture-in-picture where a person resides, observant and waiting, just beyond the traditional photographic thirds. A child, a fan or roadie, a musician only appearing by means of a mirror. The seen sound, it seems, often arrives by harmony, not merely melody.

For 1960s New York, DeCarava's work lifts up a problem as stark as the silver gelatin—race. Sadly, the publication of the sound i saw actually proves out one its visions. Both in documenting Blacks and Whites jamming together as one, and in documenting their economic disparities, the prints leave viewers changed. One cannot unsee the sound DeCarava saw.

But he sequenced the images to call out hope. The first two images develop almost a sense of dread. Coleman Hawkins stares off stage, bracing for the ominous, pictured by the hazy shade of winter bristling through the tree's barren and chattering limbs. The final two images reframe the same musician, gently beholding your gaze, knowingly but subtly nodding to the new life budding from the plant's stalk. Reaching back one more picture, we feel the longing for a different home, seen and heard most clearly by what is missing from what is in front of us.

We find ourselves standing in a similar space after experiencing the sound i saw. Its latent power unbridled, the book's images and words decry the injustices of the past but delight in the possibilities of the future. Jazz brims with possibility, as does the forward-looking heart of this book. The turn of each next page mimics the bass line with a twist, the brass's chromatic shift, the drum's snap and full stop. And then we see. There is yet beauty in God's broken world, and we hope for more to come.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.