Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Adrian Belew: Power Trios and Crimson Heads

Adrian Belew: Power Trios and Crimson Heads

AB: Well by then, Pete Sinfield was long gone from the band, so it couldn't have been his idea to call it "Red." [Laughs] Good title. Great album title and a great record.

AAJ: How does King Crimson come up with the set lists you play on the various tours?

AB: I make the set lists, actually. It's down to me. It's one of the things that Robert doesn't really care about doing, and he'd rather say, "Tell what you'd like to play tonight, Ade," and I think up something. I shuffle it around. I've got my own way of designing it to have a certain kind of contour. One night we'll play "One Time" and the next night we will play "Walking On Air," you see what I mean? You substitute one thing for another, but you want to be building a dynamic kind of flow to it. Basically, I like the idea that Robert has mentioned before. You offer a piece of candy to the audience, and when they start to take it, you punch them in the face.

AAJ: Yes, "assaulting culture," he called it. So you start with a heavy instrumental or a rocking vocal piece like "Prozac Blues," then a longer stretchy instrumental like "ConstruKction of Light," then a softer number like "One Time."

AB: Yeah, it's a contour if you look at it. You know when you've reached a peak and you settle back, give the audience a bit of air here. And then you build it back up, and obviously you want to build it to the end to a certain point you'd never reach otherwise.

AAJ: Have you never had the desire to go back and perform some of the John Wetton vocal pieces from the 1970s like "Easy Money" or "One More Red Nightmare"?

AB: Actually, "Easy Money" is a piece that has been mentioned many times. I don't know why we've never done it. I mean, it's come up. For many years, everyone was on our tails to do "21st Century Schizoid Man." We finally did that, and it was good to get that monkey off our back. [Laughs]. I don't know, I kind of feel like it's not really what the band was about. It's about pursuing new things, not redoing old things. I mean, I'm with you, though. I love all those old records. They were very important in my growth process as a young musician. Then again, so were The Beatles, and I don't want to play Beatle music.

AAJ: On the 2000 tour, King Crimson started playing David Bowie's "Heroes." How did that come about?

AB: That was Robert's idea. It was because he felt like between the two of us, we had a history with that song. Robert played on the original thing, and I played on tour with Bowie several times. We just thought that shows a bit of the undercurrent of things that Crimson touches that aren't King Crimson.

AAJ: In a recent interview elsewhere, you stated that there were no plans for King Crimson in 2009. Is that still the case?

AB: I think in 2009, there are no concrete plans. I've heard nothing as in we going to this date or something like that. Other than in my dinner conversations with Robert, where he says "We'll do some of these things next year like we are doing this year." Basically, we feel we are now at a point where we don't want to do very much touring. Just enough to where we will be out there playing, and we want to do more of what we call "hub touring," where you stay in one place—the audience comes to you. So we're playing three nights at Park West in Chicago rather than say Chicago one night, Cleveland one night, Cincinnati another night. We figure the true fans will come to Chicago on one of those three nights.

AAJ: Well, you've sold out the Belcourt Theater here in Nashville for two nights.

AAJ: Well, you've sold out the Belcourt Theater here in Nashville for two nights. AB: Yeah, I think we'll do well in the three places we've chosen—Chicago, Philadelphia and New York. What I wonder, is where else can you do that? You can't do that everywhere. Where do you do that on the West Coast? Where do you that in the South? Where do you do that in Canada? I know also that Robert has said definitively that has does not want to work outside of the United States.

AAJ: Was the 2003 tour so bad that he swore he would never tour Europe again? What happened there?

AB: I don't know what happened. Nothing happened as far as I am concerned. I thought it was a great tour. But, it definitely turned Robert off to ever touring in Europe again. I'm touring Europe in the fall with the power trio, actually.

AAJ: Was it the customs hassles or something like that?

AB: No, it was nothing like that. No, nothing to do with that. He didn't feel that the music was being served properly in the venues. I don't know. You're asking me, and I don't know Robert's mind.

AAJ: In 2009, will we see more power trio live dates as well?

AB: Yeah, my focus really is on the power trio now, as much as I can do that makes sense financially and otherwise. We have this next leg in touring that takes in Florida and the Carolinas. Then in June we go up and do some festivals in Canada. Should be really nice. Also since we're up there, we're be going to Burlington, Vermont and Troy, NewYork—some East coast things.

Then August is all King Crimson. Just in the fact that includes rehearsals, then playing shows. Following that, on the heels of that really, I am looking at the trio going to Russia. This will be the end of August.

Then in October, we do our real Fall tour of Europe which takes in a lot of places. Everything from Budapest to Amsterdam. It will be great for the trio to get all that experience under its belt before we even do our next record. By the time we do our next record, we will have played several weeks in Japan, in South America, in all of Europe, festivals, clubs, concerts, theaters, as openers, big stages with other headliners. We will be opening for Primus and for Zappa Plays Zappa at festival dates in Canada. So I am really excited to see where this is all leading. I know something is going to come of this, and it's going to be wonderful. If King Crimson wants to go a little deeper, that's fine but I don't think we're going to do a whole lot more than what is already planned.

AAJ: Do you feel like in 2009 there be any kind of new King Crimson record with new material?

AB: I don't. I don't. Robert has given me no indication that he wants new material or wants me to start writing. And it's a long process. A new King Crimson record is at least a two-year process, so if we even started in 2009, you wouldn't see anything until 2011. I really don't think that's where his focus is. I think what we want to do now is a little bit of live playing and just keep the music going. class="f-right">Return to Index...

History

AAJ: Let's talk about some of your history. I understand you played drums before you played guitar in school?

AB: Well, I started in Junior High school band. I wanted to be in marching band. I wanted to play in parades and go to football games, and that's what I did. I never truly got into the concert aspect of it, so I never got deep into the learning process of reading music. In fact, in my three years [in the] junior high school band, I mostly learned marching cadences and places to be on the football field. When I finished and moved to another area, that happened to coincide with what they called the British Invasion, so I dropped the idea of wanting to be in the school band and wanting to be in a rock band.

I joined my first rock band as a drummer and singer. I'd always been able to sing, so it was an interesting combination to be a lead singing drummer. So that was helpful, and by the time I was a junior in high school, I took up the guitar. By that time, the musician had changed. So fast. Just like it's doing now. You went from 1963 where there are these "She loves you, yeah yeah yeah" songs to 1967 where there are orchestras on the records. And you kind of go, "Wow, how do I do this now?" So it's 1967, which is really around the time I started playing guitar, and you also have the advent of the virtuoso playing. You have people like Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton. Drummers like Mitch Mitchell and Keith Moon. Wow, suddenly there is more to this than these little pop songs. And that's when I really took an interest in the guitar.

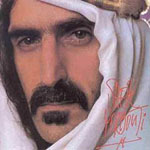

AAJ: Let's flash forward about 10 years to Frank Zappa. You were playing in a Nashville-based cover band called Sweetheart. I'm curious; did Sweetheart ever play any original material?

AB: We did actually start down the road of playing our own material. [Laughs] Here's kind of a quirky story, but I'll tell it anyway. There were three writers in the band—myself, the keyboard player and the saxophonist. They said, "We'd like to do this evenly so we'll do one of Adrian's songs, one of Rod's and one of Brian's." And that's what we did. We did one of mine, one of Rod's and one of Brian's. Then we did another one of mine, one of Rod's... and that was it because those guys ran out of songs. [Laughs]. And I said, "Hold it, I've got 50 more songs here!" So, as I recall, we learned five original songs. class="f-right">Return to Index...

Frank Zappa

AAJ: So you were playing a gig here in Nashville and Zappa gets in a taxi and says, "Take me to a good show." Is that what it was?

AB: Well, kind of. You're close. Frank played a gig in town. And this was normal for Frank, after a show he'd like to go to a club in town and try to discover musicians and discover music. He asked the limo driver, Terry Pugh. I still remember him very well. He used to come and hear Sweetheart all the time. And Sweetheart really was a great band, by the way. We didn't have very many original songs, but we were a hot commodity. And we looked great and sounded great. We did cover band stuff, but it was high quality like Steely Dan, Wings, Stevie Wonder. It wasn't your typical...

AAJ: I am just imagining you playing Steely Dan...

AB: Oh yeah, I loved Steely Dan. They had an amazing run of guitar players and music. So Frank needed something to do so he loaded up the limo with band members and crew members. They came to where I was playing at this little dank dark bar called Fanny's that was painted black on the inside. It was kind of a biker bar. Lot of motorcycle guys hung there. So yeah, he came in for 40 minutes and listened. At the end of that he came up to the stage, reached up and shook my hand.

AAJ: Did you recognize him at that point?

AB: Oh Yeah. Everybody recognized him. The minute he walked in the whole place lit up. And I tried everything I could do to impress Frank Zappa. And it worked. He said, "I'll get your name and number from the limo driver. I'll audition you when I finish my tour." He said it would be awhile. And it was. Maybe six months later he called. Right at a desperate moment in my life, just when I was about to give up he called. I was three months behind in my rent, and all kinds of bad things were going on in my life. I thought, "Maybe I should forget this and start making pizza for a living." Frank called, and that saved me life.

AAJ: So off you go to California to learn the Zappa material. And man, what a wacky catalogue of music he had. On those tours, he wouldn't play the same set list every night either.

AB: Yeah, we rehearsed for three months before we ever played a show. three months, five days a week. Long rehearsals, eight-to-ten hours a day. By the end of that time, I had learned five hours of Frank Zappa music. Before we ever stepped on a stage, I knew that much of his stuff. And, I worked with Frank privately on the weekends since I was the only musician in the band who didn't read music. He would give me time to learn things by rote which were coming up the next week. So I delved into that relationship and moved into an apartment out there. I didn't even have a car. I just totally drowned myself in Frank Zappa music. Up to that point, I didn't know much about Frank Zappa's music. I had heard a few things, but that was it.

AB: Yeah, we rehearsed for three months before we ever played a show. three months, five days a week. Long rehearsals, eight-to-ten hours a day. By the end of that time, I had learned five hours of Frank Zappa music. Before we ever stepped on a stage, I knew that much of his stuff. And, I worked with Frank privately on the weekends since I was the only musician in the band who didn't read music. He would give me time to learn things by rote which were coming up the next week. So I delved into that relationship and moved into an apartment out there. I didn't even have a car. I just totally drowned myself in Frank Zappa music. Up to that point, I didn't know much about Frank Zappa's music. I had heard a few things, but that was it. AAJ: So was that you doing the Bob Dylan impersonation on "Flakes" on Zappa's Sheik Yerbouti (Ryko/FZ, 1979) record?

AB: [Laughs] Yes. That happened one night on a weekend when I was sitting with Frank. It has this one section in the middle where... well, you see, Frank just couldn't sing and play at the same time. I found out why. When he sang while he played, he sounded like a bad folk singer. So I started making fun of what he was doing. I started singing like Bob Dylan and he said, "That's It! I want that in the show!"

AAJ: You worked on the Baby Snakes (Ryko/FZ, 1983) film with Frank. Did I read that you were present for the editing somewhere?

AB: I wasn't present for the film editing, but I was there for the filming, of course. I was in the film. What actually happened, by the end of the first year I spent with Frank, I had met David Bowie. David offered me to go on tour with him during the time that Frank would be editing the film. Frank said, "Well, I will be doing this editing for the next three months." And I told him that David Bowie would be on tour for the next four months. So I thought maybe I should go do that while he edited the film. I figured that I would return to the Zappa fold, but things didn't work out that way.

AAJ: Did you ever think about going back to Frank Zappa in the, '80s, after activity with King Crimson died down?

AB: No, I didn't. At that time, when I joined King Crimson in 1981, that was the same year I was able to do what I had wanted to do all my life, which was get my own record deal and make my own records. So, by that time I felt that I was growing on my own as my own artist, and I shouldn't try to be a sideman anymore. class="f-right">Return to Index...

David Bowie

AAJ: How did you make the transition from Zappa to Bowie? Did Bowie come to a Zappa show, was that it?

AB: Yes, in Germany. What actually happened, in Cologne, Germany, Brian Eno was in the audience for the Frank Zappa show. He knew that David Bowie was looking for a new guitarist for his upcoming tour. He called David and said, "Man, you've got to see this guy who is in Frank Zappa's band." So David came to the show a few nights later in Berlin, accompanied by Iggy Pop. There was a spot in the show where I would leave while Frank played a long solo. Usually I would just go get a drink of water and put on a costume or a different hat or something. This time, I saw David Bowie and Iggy Pop standing over by the monitor mixer, and I decided I was going to say something to David Bowie, because I'm a big fan of his. I had played some of his songs. So I shook David's hand, and I said, "Hi, I just wanted to tell you how much I love your music." He said, "Great, how would you like to be in my band?" [Laughs] That's how it happened. It was a shock.

AAJ: So did you do the tour before you recorded the Lodger (Virgin, 1979) record with David or was it vice versa?

AB: Yeah, the tour was before. We did one leg of the tour before going into the studio. As with Frank, the tours were divided into legs. Back then, you would do two months in United States, take a few weeks off, then do two months in Europe. Then, if you were lucky, you might go to Japan or South America. All that got mixed together, and somewhere in the middle of it we went to Switzerland and did the Lodger album with Brian Eno as producer. That was my first actual studio record.

AAJ: When I looked at your discography, your first album released was the Stage (Ryko, 1978) album with David.

AB: Yeah, that was recorded on that first leg of the tour. The first two records I recorded were live—one being Sheik Yerbouti with Frank, the other being Stage with David. The third was Lodger, the first time I was ever in a studio recording with someone.

AAJ: Is it true that you had to track your parts to those tunes on Lodger without ever having heard them previously?

AAJ: Is it true that you had to track your parts to those tunes on Lodger without ever having heard them previously? AB: Yeah, that's exactly right. That was the plan. The record was to be called Planned Accidents. At the time, that was the title that David and Brian had. And their idea was, "Well, let's get Adrian's responses without ever having heard it first." So, the recording room was actually above the control room. There was a camera in the recording room so the people in the control room could see me, but I couldn't see them. They said, "You're going to hear a count off. Then we want you to start playing." Well, I said, "Playing what?" They said, "Whatever you want to play." I said, "Well, what key?" They said, "We're not going to tell you." So, I would fumble my way through the song the first time. The second time I would get a few places {sounding} good. The third time, I would even start knowing maybe what was coming next, but that was it. I was never allowed to play it more than two or three times. And they took the best parts that they liked, and created a composite guitar track. So there are some really crazy parts on there that theoretically, I didn't actually play, at the same time, at least.

AAJ : I found some of the guitar parts—"DJ" and, "Boys Keep Swinging," for example—to be kind of Fripp-esque.

AB: Oh, they probably are. I was following in his footsteps. I wanted to keep in that genre. class="f-right">Return to Index...

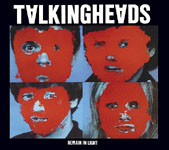

Talking Heads

AAJ: Okay, how did you get from Bowie then to the Talking Heads? Was that through Eno?

AB: No, that was through playing at Madison Square Garden with David. The Talking Heads were in the front row. They saw me, and they liked what I did. Their next tour was for a record called Fear of Music (Sire, 1979). They were touring around the Midwest. I came to three of their shows. On the third show, I played with them. They said, "Would you come up and play with us on, 'Psycho Killer?,'" which was the encore. And that was it after that.

The next time I saw them, I was playing my own show in New York City with my own band, a showcase, trying to get a record deal. When I finished the show, there was David Byrne, Jerry Harrison and Brian Eno again. They took me over into a stairwell, and they said they were making a record and asked if I could stay around and record on it. I said, "I don't know. Let me ask these other people I'm in town playing with if they would mind staying in New York an extra day. I guess they probably won't." So I did Remain In Light the next day.

AAJ: You did that all in one day?

AB: All in one day.

AAJ: Did you play on every track on the record?

AB: Most every track, yeah. I was fast. And I had lots of ideas. And it's always been that way for me. If someone plays a new piece of music for me, if it's Trent Reznor or it's David Byrne, I will say, "Wow, there's five different things I can offer here on this track. Here, I could do this, or I could this, and this, and this, and this." Basically, people have gotten to the point where when I play on someone's record they want me to do my own thing.

AAJ: To do what you do.

AB: Yeah, that's what they're asking. I'm not one of these studio players that show up and you hand me a chart and say, "Here's the chords. Here's what I want you to play. I want you to sound like this guy."

AAJ: When the Talking Heads played you the Remain in Light material before you played on it, did it strike you right away? When I listen to them now, It almost sounds like Remain in Light, [King Crimson's] Discipline (DGM Live, 1980), [Belew's] Lone Rhino (Island, 1982) and [Tom Tom Club's] Tom Tom Club (Sire, 1981) were recorded at the same time by the same band.

AAJ: When the Talking Heads played you the Remain in Light material before you played on it, did it strike you right away? When I listen to them now, It almost sounds like Remain in Light, [King Crimson's] Discipline (DGM Live, 1980), [Belew's] Lone Rhino (Island, 1982) and [Tom Tom Club's] Tom Tom Club (Sire, 1981) were recorded at the same time by the same band. AB: Well, it was a small community of the same thought. I would include Brian Eno, Talking Heads, David Bowie, maybe Peter Gabriel in that line of thinking, and certainly Robert Fripp, and myself. You have common factors that go through all those things. Brian Eno producing and me playing on a record, Robert playing on a record, then Tony Levin plays with Peter Gabriel—it all sort of connects the dots really quickly. I think it was a time when there was a real interest in African rhythms and certain other parts of music that all of us took to heart and said, "Okay, what can we do with this stuff?"

AAJ: When you first joined King Crimson, well it wasn't even called King Crimson. It was called Discipline. Was that because Robert wanted to separate himself—it was pretty much a left turn from the mellotron driven, hard, progressive rock of the '70s—since the sound of the new group was more groove-oriented?

AB: Oh, it was a totally different brand of music. I think that's why Robert was hesitant to call it King Crimson. At some point, about six weeks into the writing and rehearsing of the music, he said, "No matter what we call it, it has the spirit of and the integrity of King Crimson." Tony Levin and I almost shouted, "Let's call it King Crimson!"

AAJ: You were also on the live double album that has recently been reissued The Name of This Band is Talking Heads (Sire, 1982).

AB: Right. I've never actually heard that.

AAJ: Ha. Well, you should just hear yourself; lots of great Remain In Light material on there, must have been from that tour, on disc two. And on the first disc are tunes from the previous tours before you joined. It was interesting to hear their music progress.

AB: Yeah, well they took a big leap from album to album. They progressed really well. I followed their progression from album to album. Then, I really loved Fear of Music, which was the last album before I joined them. Then, Remain in Light seemed like a real departure. All of sudden, Remain in Light (Sire, 1980) came out of nowhere. I thought up to that point they sounded like a four-piece rock band, they kept their arrangements to that. They didn't have a lot of other parts, all the way up to Fear of Music, it was that way. Then with Remain in Light, all of a sudden they burst out with all kinds of backup harmonies, and extra rhythms and other players. It just took another turn there. It was difficult to do that music live. Because they hadn't planned on that, I think. They hadn't really thought out, "Well, how are we going to play this stuff live?"

AAJ: Had you been listening to Fela Kuti or some of those other African Afrobeat musicians?

AB: No, no.

AAJ: Well, they would've had to. On the reissue of Remain in Light, there is even a bonus track of them just jamming called, "Fela Groove." I guess that was David Byrne who was getting into that.

AB: Or, it could've been Chris and Tina. They were all interested in ethnic music and world music. I mean, Chris and Tina lived in the Bahamas. They worked with a lot of Jamaican players. It could've been any of those things. I know that David and Brian Eno both had a big interest in that. But no, I just kind of walked into that and felt comfortable with it. I didn't really need to go and study those records. I mean, I grew up as a drummer, so rhythms were not new to me. class="f-right">Return to Index...

Joining King Crimson

AAJ: So what was the transition that took you out of the Talking Heads and into King Crimson?

AB: Basically, Robert offered the position to be in a band with him and Bill Bruford. These were two of my favorite musicians growing up. Bill Bruford was, in fact, my favorite drummer.

AAJ: Were you a Yes fan, back in the day, then?

AB: I was a Yes fan and King Crimson. Of the progressive bands, those were the two I liked the most. And, I really loved Bill's playing, and I knew everything Robert had done. So, for me, that was really a no-brainer. I said, "Okay, I'll do that."

AAJ: Better King Crimson than continuing in a sideman role in the Talking Heads.

AB: As I was saying, in that period, 1981, I was able to break out of the shell of side man and stunt guitarist (as Frank called me). Here I'm being offered to make my own music and make my own music in collaboration with Robert Fripp, Bill Bruford and Tony Levin. So, "Wow! What a big step!"

AAJ: You know, I found it interesting that on one of the Discipline Global Mobile releases, a 1981 show that the four of you performed as Discipline, but even though you were called Discipline, you still performed, "Red" and, "Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Pt. 2." It was almost as if King Crimson was inevitable.

AB: Pre-ordained, I think. [Laughs]

AAJ: So you played on a Herbie Hancock record that same year—Magic Windows (Columbia, 1981). It's currently only available on CD as an import, so I'm not really sure what it sounds like, but what was it like to record with Herbie Hancock?

AB: It was great. It was just me and him and a studio full of keyboards. [Laughs] Herbie used to come see some of the King Crimson shows in the early, '80s, so he was a fan. He was a really nice person. In fact, he is one of the earliest people to say, "I think you wrote some of this material, so I'm going to give you a co-writing credit." So we wrote one of the songs on that record together.

AB: It was great. It was just me and him and a studio full of keyboards. [Laughs] Herbie used to come see some of the King Crimson shows in the early, '80s, so he was a fan. He was a really nice person. In fact, he is one of the earliest people to say, "I think you wrote some of this material, so I'm going to give you a co-writing credit." So we wrote one of the songs on that record together. It was fun to do that, and a little scary for me because I've never considered myself educated in the world of jazz. I listen to jazz, but I find it fascinating that even as a drummer I have no idea was those jazz drummers are thinking or doing. So, to play with Herbie Hancock, a bona fide jazz musician with a name, was a bit scary. I was hesitant a little bit. I said, "I don't know. What do you want me to do?" He just said, "Do what you do. I love what you do with King Crimson. Keep doing it. Do what you do on my record." So we could break through the barrier where you don't have to sit and talk through a piece of music in other language than playing the music. That is the language you use.

AAJ: So you wouldn't describe it as a straight-ahead bebop kind of record?

AB: No, I wouldn't. He was going a lot more outside, using synthesizers and doing other things.

AAJ: He had a lot of success with that type music in the, '80s, with the, "Rockit" single and all. So on top of all the things, you played with one of the great jazz pianists of all time.

AB: And it was an honor.

AAJ: Why did King Crimson only make it up to about 1984 and then disappear for 10 years?

AB: You've asked me so many questions that would be answered by Robert, not me. I found out that the band was over by reading Musician magazine. I didn't have any idea. Robert never called me or anything else. A friend of mine said, "You should look at the new issue of Musician magazine. It says that King Crimson's broken up." So, I don't know why that happened. Robert felt that the band had gone away from his original vision of it.

AAJ: Too commercial? Is that what it was?

AB: Well, it wasn't commercial. It was never commercial. It was never meant to be commercial. Lord help us if King Crimson ever got on the radio. [Laughs]

AAJ: I thought that some of those tunes like "Heartbeat," for example, could've been a hit.

AB: Yeah, I sometimes regret that song being put in the hands of King Crimson, because I was talked into it.

AAJ: So "Heartbeat" was one of your tunes?

AB: Yeah, I totally wrote the song by myself. I was talked into it mainly by Bill Bruford who said, "Let's see what happens if we put a song like this in the mix." And I think that probably is the beginning of Robert feeling like this has gone totally different than I wanted. He runs away from popularity.

AAJ: So I've heard. I'm interested in the writing process for the '80s King Crimson—say, "Frame By Frame" and the Discipline album. Did you write that? Did Robert write that? How were those tunes written?

AAJ: So I've heard. I'm interested in the writing process for the '80s King Crimson—say, "Frame By Frame" and the Discipline album. Did you write that? Did Robert write that? How were those tunes written? AB: Mostly it's Robert and I who do all the writing. The other players, be it Trey Gunn and Pat Mastelotto or Tony and Bill come up with their parts, but you have to have the blueprint, which is, "What are we playing here? What is the tempo? The time signature? The changes? The notes we are playing to." That's called writing the music, and that's done by me and Robert. Usually in the room that you're sitting in. Quietly, we don't even plug our instruments in because we aren't trying to get sounds and develop solos.

You mentioned, "Frame By Frame." We started with this riff in 7. [Sings the riff]. Now what would you do with that? Well, I could sing this over that. Where would you go from there? Well, I'd have to have it move up to another key somewhere because I don't want to stay in the same key—we're not making another Remain In Light album. [Laughs] So, that's how it goes. It goes in spurts like that. You start out with a simple—well I wouldn't say simple—idea. And you take it as far as you can, day after day. Then we walk away from each other for days or months, even. Then you come back and you say, "What's happened? Well, I've taken that idea we had and added this to it." Or, "I've got this new thing."

Robert and I just bounce the ball back and forth in that way. A lot of the ideas start with him. And end with me. I've learned over the years working with Robert that the best way to work with him is to have his involvement from the beginning. Rather than write a song like, "Heartbeat" and bringing it to the band, I prefer to say "Robert, let's sit down and do you have any thoughts? Here's something I've been working on, let's work on that." And also, there are developmental times where you have a piece of music, and you just need to find its form. You know what the parts are, you know where you want to take it, but you don't know the best arrangement. So, at that time, you bring in the whole band, and you start trying different ways of playing things.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.