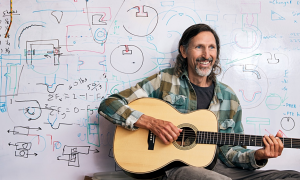

If you close your eyes, songwriter Mike Stoller sounds remarkably like comedian Larry David. The tone is distinctly New York—insistent and street smart. But unlike David, Mike's voice has tones that are more nasal and much gentler, the result of an upbringing in Queens, a borough of New York that's halfway to the suburbs of Long Island.

Mike likes things simple, and leaves the angst and analysis to others. One senses that he likes to keep things light, relying on humor to deflect negative thinking and reflecting on life's ironies from the perspective of a spectator rather than a participant or victim. [Photo of Mike Stoller and wife Corky Hale in March 2012 by Andrew H. Walker/Getty Images North America]

In Part 2 of my conversation with Mike for the Wall Street Journal (go here to read my profile), the R&B songwriter reflects on co-composing Jailhouse Rock, his role in helping R&B crossover to white markets in 1957, and his writing partner Jerry Leiber:

Marc Myers: Jailhouse Rock in 1957 was something of a turning point for R&B and rock, wasn't it?

Mike Stoller: In what way?

MM: Elvis had his 1956 run and becomes larger than life, the civil rights movement shifts gears, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis add a wild streak, the Coasters, Drifters and Platters cross over, images of racial strife appear on TV and in print, and there are several major political events ofhte year. In this context, Jailhouse Rock sounds like something of a generational bond-cutter.

MS: Interesting. But it's not that different thematically from Riot in Cell Block #9 though, don't you think?

MM: I don't know. To me, there's a different edge—a towel-snap feel to the words and music that's less about a whimsical prison uprising and more about flaunting authority, rebelling against your captors—teachers, parents and so on. It's a clarion call, and I think that's why it crossed over and resonated. MS: Good point. And yet there's playfulness to it, too. The song doesn't feel unsafe. [Pictured: Elvis Presley on the set of Jailhouse Rock in 1957]

MM: Exactly, which is so true of many of your songs. Humor crosses all barriers. The movie version of Jailhouse Rock and the record have different instrumental approaches, yes?

MS: Yes. I had nothing to do with the movie's orchestration. The record was made first and became the template for the movie. The movie folks wound up doing an expanded orchestral version because of the visual choreography.

MM: What do you think of the movie version?

MS: I like it. It was funny. The record also was visual, but in one's imagination. I thought that Elvis's dancing performance in the movie was wonderful.

MM: How did you come to write that blues? It has a Freddie Slack feel.

MS: [Laughs]. Freddie Slack! I haven't heard that name in ages. The melody just came. It's based on the kind of blues breaks that had been part of the blues literature, so to speak. I just tried to find a way to make it a little different. Jerry and I wanted to create a style that we felt would be easy for Elvis to relate to and sing.

MM: The lyrics are a little homoerotic in places, no?

MS: You mean, “Number 47 said to Number. 3, you're the cutest jailbird I ever did see?" Nah. It's whatever you think it means. There's an edge but none of that was intended.

MM: Despite the whimsy, there's a dark edge to that song. What inspired it?

MS: We were given a script. In the script, there was a note in brackets that simply said, “There's a talent contest in prison" [laughs].

MM: [Laughing] That's rich. That was it?

MS: That's all. But you know, we didn't read the whole script when we first got it. In fact, we just thumbed it. We got the script in New York. [Photo: Mike Stoller at the piano]

MM: Why were you in New York?

MS: After I returned from Europe in 1956 and Jerry told me about Hound Dog becoming a big hit for Elvis, I checked into the Algonquin Hotel, where Jerry was staying. That night we went to dinner at the Russian Tea Room. That's when I first met the guys at Atlantic— Ahmet Ertegün, the label's founder; Jerry Wexler, the label's producer, and Herb Abramson, who produced at Atco, an Atlantic subsidiary. Ahmet and his brother Nesuhi Ertegun, who ran the jazz side, took us to dinner. Then went to the old Basin Street to hear the Modern Jazz Quartet.

MM: So you remained in New York?

MS: We began writing for the Coasters, who had signed with Atco. We had been writing for them and producing their records when they were known as the Robins. Jerry and I took an apartment on East 71st St. It was a six-month sublet. After the lease was up, we went home to L.A. Then in March 1957, we returned to N.Y. to hang out with Ahmet and Jerry Wexler. By then, we had had some successes with Elvis, and Colonel Parker, Presley's manager, wanted us to write the music to his next movie, Jailhouse Rock. So we went up to Hill & Range, the music publishing company that controlled Elvis' music, to pick up the script.

MM: What did you do with the script?

MS: When Jerry and I got back to our hotel suite on West 55th St., we tossed it on the corner table, on top of a bunch of hotel magazines. Then we set out to enjoy New York.

MM: What did you do?

MS: We spent the next few weeks going to jazz clubs and cabarets and the theater. I remember we went to see Cy Coleman and his trio. Ray Mosca was on drums. I had gone to high school in Queens with Ray before my family moved to L.A. in 1949.

MM: What motivated you and Leiber to finally pick up the script?

MS: Weeks later, Jean Aberbach, a co-owner of Hill & Range, showed up at our hotel unannounced. It was a Saturday, and Jerry and I were having breakfast. Jean said, “Fellows, where are my songs?" Jerry said, “Don't worry Jean, you'll have your songs." We both glanced over at our script in the corner.

MM: What did Aberbach say?

MS: He said, “I know I'll have my songs, boys, because I'm not leaving here until I do."

MM: What did he do?

MS: Jean got up and pushed a big overstuffed chair against the door. He said, “I'm going to take a nap, and I'm not leaving until I have them."

MM: How long did his nap last?

MS: About four hours. When he woke up, four songs were done.

MM: Which ones?

MS: Jailhouse Rock, Treat Me Nice, (You're So Square) Baby I Don't Care and I Want to Be Free. All sort of related to being cooped up in that suite [laughs].

MM: What was going on inside the music business regarding civil rights in 1957?

MS: I can only tell you what we experienced, as I experienced it. In terms of integration, it wasn't an issue. Jerry and I had been writing, creating and recording in an integrated community from 1950. Only later, in the 60s, were there schisms in the music industry in response to the black power movement, when some of our relationships grew uncomfortable.

MM: Were you conscious of the civil rights movement?

MS: We were conscious of it to a degree. We were aware that what we had experienced in our lives, in our early lives with our interracial relationships, was starting to happen nationwide.

MM: Was the movement a conscious part of your music?

MS: No. It was just the music Jerry and I loved. The music had always been integrated for us. We were simply creating songs that were extensions of our own interracial experiences.

MM: Was there pushback by white record executives asking you to write in a certain way—to avoid trouble in the South, for example?

MS: Never. Not at all. Our songs actually sold well in the South, particularly in black communities. We'd see our songs in Cash Box on the R&B charts that covered 16 different markets. There was a chart for Harlem, Chicago South Side, Shreveport, Kansas City and so on. Each chart had different songs rising and falling as opposed to the pop chart, which was a national thing.

MM: Did you feel that what you and Leiber were doing was maverick from a civil rights perspective?

MS: We weren't really political. We didn't think of it that way. We weren't devoid of any sense of what was going on. Nor were we were devoid of racial politics, and right and wrong. But there was no black and white for us. We were writing what appealed to us, which happened to be mostly music performed and recorded by black artists. We were entertaining ourselves when we wrote. Our backgrounds had erased all of that.

MM: How so?

MS: I had gone to an interracial summer camp from age 7 to 15, and Jerry had lived a different experience—though similar in terms of his exposure to black families. His mother ran a little store in Baltimore, and Jerry delivered soft coal and kerosene to the black community on the edge of where he lived. He had relations with black kids and dated black girls. We both did. Jerry was welcome there because he was literally delivering the light.

MM: How did you two meet?

MS: When we were still in our late teens in 1950, Jerry called me out of the blue and said he was a songwriter. He said he had heard about me from a drummer he knew and asked if I wanted to write songs with him. I said I wasn't interested in writing pop songs. Less than an hour later, Jerry showed up at my front door with pages of lyrics. When I saw they were in the form of 12-bar blues, I agreed to write with him. I loved the blues.

MM: Was Leiber a nice guy?

MS: Yes. Sometimes he was tormented. Sometimes he was extremely generous. He was complex.

MM: Do you miss him?

MS: Yeah. I miss... [pauses]. I miss the kid I met in 1950. The ambitious, aggressive, dynamic and exciting kid. Jerry used to say to me when we drove around in my '37 Plymouth, “We're going to be rich and famous." I thought he was deluding himself.

MM: Your pragmatism was offset by his dreaming?

MS: I guess so. Jerry used to say he had no brakes and I had no motor.

MM: What did he mean?

MS: That he might go off in a direction at any given moment. Without me to hold him back, he might have gone off the edge of the world. But without that streak, I wouldn't have been motivated. Which was the no-motor part.

MM: You guys were pretty prolific for you to have been unmotivated.

MS: Oh, I was plenty motivated to write but not to promote myself. I was very shy. But together it worked.

MM: Are you still shy?

MS: No, I don't think so.

MM: Was that a result of Leiber?

MS: Maybe. But at a certain point in our relationship... It's weird. Early on, in interviews, Jerry did all the talking. And then at a certain point in our relationship, that shifted. He acknowledged that. I can't pinpoint the date. It just changed.

JazzWax clips: Here's Jailhouse Rock, the record...

And here's Jailhouse Rock, the movie version...

Mike likes things simple, and leaves the angst and analysis to others. One senses that he likes to keep things light, relying on humor to deflect negative thinking and reflecting on life's ironies from the perspective of a spectator rather than a participant or victim. [Photo of Mike Stoller and wife Corky Hale in March 2012 by Andrew H. Walker/Getty Images North America]

In Part 2 of my conversation with Mike for the Wall Street Journal (go here to read my profile), the R&B songwriter reflects on co-composing Jailhouse Rock, his role in helping R&B crossover to white markets in 1957, and his writing partner Jerry Leiber:

Marc Myers: Jailhouse Rock in 1957 was something of a turning point for R&B and rock, wasn't it?

Mike Stoller: In what way?

MM: Elvis had his 1956 run and becomes larger than life, the civil rights movement shifts gears, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis add a wild streak, the Coasters, Drifters and Platters cross over, images of racial strife appear on TV and in print, and there are several major political events ofhte year. In this context, Jailhouse Rock sounds like something of a generational bond-cutter.

MS: Interesting. But it's not that different thematically from Riot in Cell Block #9 though, don't you think?

MM: I don't know. To me, there's a different edge—a towel-snap feel to the words and music that's less about a whimsical prison uprising and more about flaunting authority, rebelling against your captors—teachers, parents and so on. It's a clarion call, and I think that's why it crossed over and resonated. MS: Good point. And yet there's playfulness to it, too. The song doesn't feel unsafe. [Pictured: Elvis Presley on the set of Jailhouse Rock in 1957]

MM: Exactly, which is so true of many of your songs. Humor crosses all barriers. The movie version of Jailhouse Rock and the record have different instrumental approaches, yes?

MS: Yes. I had nothing to do with the movie's orchestration. The record was made first and became the template for the movie. The movie folks wound up doing an expanded orchestral version because of the visual choreography.

MM: What do you think of the movie version?

MS: I like it. It was funny. The record also was visual, but in one's imagination. I thought that Elvis's dancing performance in the movie was wonderful.

MM: How did you come to write that blues? It has a Freddie Slack feel.

MS: [Laughs]. Freddie Slack! I haven't heard that name in ages. The melody just came. It's based on the kind of blues breaks that had been part of the blues literature, so to speak. I just tried to find a way to make it a little different. Jerry and I wanted to create a style that we felt would be easy for Elvis to relate to and sing.

MM: The lyrics are a little homoerotic in places, no?

MS: You mean, “Number 47 said to Number. 3, you're the cutest jailbird I ever did see?" Nah. It's whatever you think it means. There's an edge but none of that was intended.

MM: Despite the whimsy, there's a dark edge to that song. What inspired it?

MS: We were given a script. In the script, there was a note in brackets that simply said, “There's a talent contest in prison" [laughs].

MS: That's all. But you know, we didn't read the whole script when we first got it. In fact, we just thumbed it. We got the script in New York. [Photo: Mike Stoller at the piano]

MM: Why were you in New York?

MS: After I returned from Europe in 1956 and Jerry told me about Hound Dog becoming a big hit for Elvis, I checked into the Algonquin Hotel, where Jerry was staying. That night we went to dinner at the Russian Tea Room. That's when I first met the guys at Atlantic— Ahmet Ertegün, the label's founder; Jerry Wexler, the label's producer, and Herb Abramson, who produced at Atco, an Atlantic subsidiary. Ahmet and his brother Nesuhi Ertegun, who ran the jazz side, took us to dinner. Then went to the old Basin Street to hear the Modern Jazz Quartet.

MS: We began writing for the Coasters, who had signed with Atco. We had been writing for them and producing their records when they were known as the Robins. Jerry and I took an apartment on East 71st St. It was a six-month sublet. After the lease was up, we went home to L.A. Then in March 1957, we returned to N.Y. to hang out with Ahmet and Jerry Wexler. By then, we had had some successes with Elvis, and Colonel Parker, Presley's manager, wanted us to write the music to his next movie, Jailhouse Rock. So we went up to Hill & Range, the music publishing company that controlled Elvis' music, to pick up the script.

MM: What did you do with the script?

MS: When Jerry and I got back to our hotel suite on West 55th St., we tossed it on the corner table, on top of a bunch of hotel magazines. Then we set out to enjoy New York.

MS: We spent the next few weeks going to jazz clubs and cabarets and the theater. I remember we went to see Cy Coleman and his trio. Ray Mosca was on drums. I had gone to high school in Queens with Ray before my family moved to L.A. in 1949.

MM: What motivated you and Leiber to finally pick up the script?

MS: Weeks later, Jean Aberbach, a co-owner of Hill & Range, showed up at our hotel unannounced. It was a Saturday, and Jerry and I were having breakfast. Jean said, “Fellows, where are my songs?" Jerry said, “Don't worry Jean, you'll have your songs." We both glanced over at our script in the corner.

MS: He said, “I know I'll have my songs, boys, because I'm not leaving here until I do."

MM: What did he do?

MS: Jean got up and pushed a big overstuffed chair against the door. He said, “I'm going to take a nap, and I'm not leaving until I have them."

MM: How long did his nap last?

MS: About four hours. When he woke up, four songs were done.

MS: Jailhouse Rock, Treat Me Nice, (You're So Square) Baby I Don't Care and I Want to Be Free. All sort of related to being cooped up in that suite [laughs].

MM: What was going on inside the music business regarding civil rights in 1957?

MS: I can only tell you what we experienced, as I experienced it. In terms of integration, it wasn't an issue. Jerry and I had been writing, creating and recording in an integrated community from 1950. Only later, in the 60s, were there schisms in the music industry in response to the black power movement, when some of our relationships grew uncomfortable.

MS: We were conscious of it to a degree. We were aware that what we had experienced in our lives, in our early lives with our interracial relationships, was starting to happen nationwide.

MM: Was the movement a conscious part of your music?

MS: No. It was just the music Jerry and I loved. The music had always been integrated for us. We were simply creating songs that were extensions of our own interracial experiences.

MS: Never. Not at all. Our songs actually sold well in the South, particularly in black communities. We'd see our songs in Cash Box on the R&B charts that covered 16 different markets. There was a chart for Harlem, Chicago South Side, Shreveport, Kansas City and so on. Each chart had different songs rising and falling as opposed to the pop chart, which was a national thing.

MS: We weren't really political. We didn't think of it that way. We weren't devoid of any sense of what was going on. Nor were we were devoid of racial politics, and right and wrong. But there was no black and white for us. We were writing what appealed to us, which happened to be mostly music performed and recorded by black artists. We were entertaining ourselves when we wrote. Our backgrounds had erased all of that.

MM: How so?

MS: I had gone to an interracial summer camp from age 7 to 15, and Jerry had lived a different experience—though similar in terms of his exposure to black families. His mother ran a little store in Baltimore, and Jerry delivered soft coal and kerosene to the black community on the edge of where he lived. He had relations with black kids and dated black girls. We both did. Jerry was welcome there because he was literally delivering the light.

MS: When we were still in our late teens in 1950, Jerry called me out of the blue and said he was a songwriter. He said he had heard about me from a drummer he knew and asked if I wanted to write songs with him. I said I wasn't interested in writing pop songs. Less than an hour later, Jerry showed up at my front door with pages of lyrics. When I saw they were in the form of 12-bar blues, I agreed to write with him. I loved the blues.

MM: Was Leiber a nice guy?

MS: Yes. Sometimes he was tormented. Sometimes he was extremely generous. He was complex.

MS: Yeah. I miss... [pauses]. I miss the kid I met in 1950. The ambitious, aggressive, dynamic and exciting kid. Jerry used to say to me when we drove around in my '37 Plymouth, “We're going to be rich and famous." I thought he was deluding himself.

MM: Your pragmatism was offset by his dreaming?

MS: I guess so. Jerry used to say he had no brakes and I had no motor.

MM: What did he mean?

MS: That he might go off in a direction at any given moment. Without me to hold him back, he might have gone off the edge of the world. But without that streak, I wouldn't have been motivated. Which was the no-motor part.

MS: Oh, I was plenty motivated to write but not to promote myself. I was very shy. But together it worked.

MM: Are you still shy?

MS: No, I don't think so.

MM: Was that a result of Leiber?

MS: Maybe. But at a certain point in our relationship... It's weird. Early on, in interviews, Jerry did all the talking. And then at a certain point in our relationship, that shifted. He acknowledged that. I can't pinpoint the date. It just changed.

JazzWax clips: Here's Jailhouse Rock, the record...

And here's Jailhouse Rock, the movie version...

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.