Home » Jazz Articles » Jazz West Coast » The Los Angeles Jazz Scene of the 1950’s from Robert Gor...

The Los Angeles Jazz Scene of the 1950’s from Robert Gordon’s “Jazz West Coast”

After a short break the musicians decided to try the ballad "Lover Man."-Charlie, in the meantime, had taken some barbiturates in an attempt to settle his protesting muscles. Pianist Jimmy Bunn began a quiet introduction, but Bird missed his cue and came in a few bars late. Charlie's tone on the performance is haunting, the equivalent of a vocalist about to burst into tears. He stays close to the melody at first, then gains a measure of confidence and launches into flight. The notes come in flurries, in seemingly random phrases that manage somehow to fit into a satisfying whole. It's a technique that Charlie often uses on ballads, but here he seems dangerously close to losing altogether. He's the high-wire artist, working without a who slips and stumbles, yet never falls. The performance, all its obvious faults, is strangely and deeply moving.

Lover Man—Charlie Parker—1946

"The Gypsy," a ballad that Charlie had been playing nightly at Finale, came next. Here, Charlie lost the control he had tenuously gained on "Lover Man." His performance is deliberate and plodding, a walk-through that takes no chances whatsoever, dull as Sunday-morning TV. Charlie's final tune was the minor key "Bebop," taken at a disastrously fast tempo. The ensemble passages are exceedingly sloppy and Charlie's solo simply peters out; even two great choruses by Howard McGhee aren't enough to save the piece. Charlie brought the tune to a close with an unnerving whimper on his alto, then collapsed in an armchair—obviously finished for the night. Off in another comer, one of the few visitors sat taking notes. This was Elliott Grennard, Hollywood correspondent for Billboard, and he would later pen a prize-winning short story for Harper's entitled "Sparrow's Last jump," based on the evening's events.

Charlie was driven back to the hotel he was staying at by a man named Slim, the custodian and equipment man at the Finale. Slim was charged with putting Bird to bed and staying with him for the night. In the meantime, Russell and the musicians hoped to salvage the session with some quartet recordings. After a short break for sandwiches, Howard and the rhythm section quickly ran down two new tunes. The musicians, freed from the earlier tensions, were finally able to relax, and the recording went apace. The first tune, released under the title "Trumpet at Tempo," was Howard's fiery improvisation on "Back Home in Indiana." The second piece, "Thermodynamics," was a relaxed reworking of an obscure minor-key Ellington tune. Ross Russell thought these performances of little commercial value, due to their thin instrumentation, but they are minor bebop classics, and their reissue on a Spotlite LP has been enthusiastically greeted by collectors.

The session finished, Russell drove by Charlie's hotel to see how the altoist was doing, but Bird had disappeared. The story, pieced together afterwards, was this. Slim had indeed put Charlie to bed but, contrary to directions, had then left. A short time later Charlie had appeared in the hotel lobby seeking change for a pay telephone, there being no phones in the rooms. Unfortunately, he was stark naked. Charlie seemed unaware of his state of undress and couldn't understand the commotion he was causing. The manager, after a short shouting match, persuaded Charlie to return to his room. A short time later the scene was repeated, and this time the manager led Charlie back to his room and locked him in. About half an hour later, smoke was seen billowing from beneath the door of the room. The manager called the fire department then rushed up to the room and unlocked the door. Charlie had fallen asleep while smoking and his mattress had caught fire. A fire engine soon arrived, followed closely by the police. Charlie, roused from a drugged sleep and still naked, wandered about shouting at the people who were invading his privacy. He was promptly sapped by the police for his trouble and driven off to be booked. Russell tried desperately to find Charlie to bail him out, but the police weren't cooperating.

Charlie was finally located, ten days later, in the Psychopathic Ward of the Los Angeles county jail. He was charged with committing arson.

The upshot of the affair was that Charlie was ordered to be confined for six months at Camarillo State Hospital. As traumatic as the experience must have been, it probably was a fortunate thing to have happened to Charlie at the time. He had been going downhill fast, and it's conceivable that the stay at Camarillo may have saved his life. Camarillo is a small town halfway up the coast between Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. It boasts the sort of weather that city fathers and Chambers of Commerce dream about. The state hospital lies several miles out of town, nestled between the foothills and truck farms. At the time, it was considered the country club of the state hospital system, housing neither dangerous psychotics nor the criminally insane. Physically, Charlie prospered during his stay. The regular hours, balanced diet, healthful climate and above all the absence of drugs and alcohol all helped to restore his well-being. As his health improved, however, Charlie was increasingly agitated by the confinement. Hospital officials dragged their feet over Bird's release, unconvinced that he could face the rigors of the outside world. Finally, Ross Russell, by agreeing to have Charlie released into his custody, managed to get Charlie sprung. He was released towards the end of January 1947.

Once again, Howard McGhee came through. Howard had just contracted to bring a band into the Hi-De-Ho club on Western Avenue. He promptly offered Charlie a spot in the group as co-leader, at a salary of two hundred dollars a week. Charlie was never more ready, and soon proved that he hadn't lost his touch while at Camarillo. Despite the importuning of the pushers and local hipsters, he stayed clear of drugs, although he did continue to drink heavily. He just wanted to make the gig and save a little money so he could make it back to New York. He was physically fit and blowing better than ever. It seemed like an auspicious time to record.

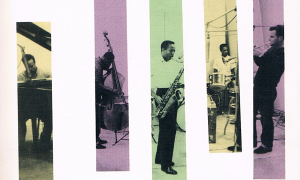

Ross Russell and Charlie discussed a "farewell" recording session. They planned on using the cream of the musicians then available on the Coast. Howard would be on trumpet, of course, and as a third horn they planned to use the rising young tenor saxophonist Wardell Gray. The rhythm section would consist of Dodo Marmarosa, guitarist Barney Kessel, bassist Red Callender and Don Lamond, Woody Herman's fine drummer.

Arrangements for this session had just about been set when Charlie suggested adding a vocalist, a young baritone he had heard in a Central Avenue club named Earl Coleman. This panicked Ross Russell. He didn't want or need a vocalist, and felt sure one would wreck the session. Thinking quickly, he came up with a counter-offer. Why not record Earl Coleman at a separate session devoted strictly to his vocals? To Russell's relief, Charlie agreed.

Russell phoned around and soon came up with a rhythm section for the vocal date. The Erroll Garner trio, with Erroll on piano, Red Callender on bass and Harold "Doc" West on drums, was available. Russell talked with Garner, who agreed to play the session if he could cut a couple of additional trio sides. Everything was set. The musicians met at the C.P. Macgregor studios in Hollywood on 17 February. Three hours of studio time had been reserved, and it took two hours to record acceptable takes of the two Earl Coleman vocals, "This is Always" and "Dark Shadows." The first is a ballad in the Billy Eckstine mode and the second a blues. Despite Russell's misgivings, the two sides have held up well over the years—especially "Dark Shadows," which features a moving chorus by Bird. However, by the time the two tunes were completed, Earl Coleman's voice was failing. Russell recalls what happened next:

At that point, Earl had had about enough; his pipes were beginning to give out on him. So Charlie Parker kinda cranked up, and they tossed off a blues. They did three takes—bang, bang, bang. The first two were too fast. Garner didn"t like the tempo, and we slowed the takes down a little. One of the fast takes was released as "Hot Blues," and the slow, "Cool Blues." As soon as that was finished, they made an ad lib improvisation on "I Got Rhythm." Three takes on this—bang, bang, bang. The interesting thing is that Bird played a little differently with Erroll Garner. Some of the very hip people didn"t like what happened; but I think a very interesting performance resulted on this date.

Russell's memory is a bit hazy here; the "I Got Rhythm" number was in fact taken first. Back in top form, Charlie reeled off superior solos on each take, and all three versions eventually found their way onto 78s under the title "Bird's Nest." There were actually four takes of the blues. As Russell mentions, Garner felt uncomfortable with the tempo on the first two. (These were later released as "Hot Blues" and "Blowtop Blues.") On the slower third and fourth takes, however, the band cooks as if the musicians had been working together for years. The third take, chosen for release, is one of Parker's great recorded performances. Bird's solo on "Cool Blues" swings hard yet is utterly relaxed, while Erroll forgets his usual mannerisms and really digs into the guts of the blues.

In fact, despite Russell's initial misgivings, the entire date turned out to be an unqualified success. The two impromptu performances by the quartet were critical as well as popular successes; "Cool Blues" won the Grand Prix du Disque when it was released in France the following year. The two Erroll Garner Trio selections, "Pastel" and "Trio," were equally well received. And to top everything off, Earl Coleman's version of "This is Always" became a surprise hit, outselling everything in the Dial catalogue.

Charlie's farewell session took place a week later, on 26 February. The day before there had been a short rehearsal at the studio. Charlie had brought in a new tune which he had scribbled down while riding over in the cab. Most of the session was spent in running down the new tune, a blues with a complex, sinuous melody line. The rehearsal ended with the musicians mumbling over the difficulty of the new piece. Next day, Charlie was late for the actual recording session. Howard McGhee found him a couple of hours later asleep in his bathtub, fully clothed, where he had crashed the night before. Back at the studio, Charlie revived himself with black coffee while Howard rehearsed the rest of the band on three originals he had brought in for the date. Finally, Charlie was ready and they started working on his new tune. It took five attempts to get an acceptable take. Charlie's solos on all five were top-notch, but the ensembles were ragged on the first four, as the other musicians struggled with the complex rhythms of the melody line. All of the solos on the final take are extremely relaxed, as if the musicians could breathe easier once the tortuous head had been negotiated. The tune was released under the title "Relaxin' at Camarillo," and it is a classic statement of the blues in the modern jazz idiom.

Charlie Parker relaxin at the Camarillo

The other three tunes recorded during the session are all fine, workmanlike performances, but they suffer in comparison with "Relaxin." The next tune, "Cheers," is a slightly-above-medium piece with an undistinguished, boppish melody. "Carvin' the Bird" is another blues, slightly faster but less intense than "Relaxin" at Camarillo." As jazz writer Ira Gitler has noted elsewhere, it's Bird who does the carving. Wardell Gray, whose tenor sax exhibits a Lester Youngish tinge throughout the date, comes on very much like Prez: in his solo on "Carvin." The final tune, "Stupendous," is based on the old standby "S Wonderful." All in all it was a very successful date and a fitting farewell to the Coast for Parker.

A few days later Charlie finally caught a plane back to New York. His stay in California hadn't been a happy one, and he was more than eager to return to a milieu where his talents were more appreciated. Physically, he was in much better shape when he left than when he had arrived, but that would prove to be a short-lived respite; he later returned to drugs. Musically, he was at the top of his form, and it is generally agreed that the years 1947 and 1948 saw the peak of Birds creativity. The records he cut in New York in those years for Dial and Savoy are considered among his greatest legacies. The Dials that Charlie cut in California are worthy additions to his canon, and the best of them ("Ornithology," "Night in Tunisia," "Cool Blues" and "Relaxin' at Camarillo") rank with any records he ever made."

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.