Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Jim Snidero: A Tale Of Taste

Jim Snidero: A Tale Of Taste

Courtesy John Abbott

Jim Snidero first came on the scene in the early '80s, already exhibiting many of the aspects of good taste and judgment that would later come to define his work. But that was hardly the start of the Jim Snidero story; that story begins in Camp Springs, Maryland where he grew up. Snidero, like many professional players, credits one of his earliest teachers—who he reconnected with shortly before this interview—as the force behind his jazz awakening. He notes, "I just spoke with my ex-junior high band director who was a jazz alto saxophonist, and he came in during my second year in middle school/junior high school; it was really because of him that I got into jazz. I was playing saxophone from age ten, but when he came in, he started a jazz band and I knew right then; it's one of those things you hear about. I knew when we did our first rehearsal with the big band, when I was 13 years old, that that was what I was going to do. And he was very nice and nurturing. He took me to great music shops, and he talked my parents into getting that Selmer Mark VI, which was a lot of money back then. He thought I had some talent I guess. And I started taking private music lessons from a store in town, and just got really turned on to jazz."

At the same time that Snidero was being inspired within the walls of his school, he was also being guided by other musical forces in the outside world. "I had a private teacher that was very good, and he turned me on to [saxophonist] Phil Woods" Snidero says. "So, by the time I was fourteen years old, I was listening to that and I started to get into other guys too, but Phil Woods was really important to my development because I saw him play live many times when I was really young and I took lessons with him when I was a teenager, and it just gave me such a great model of artistry and saxophone playing. To see that live at such a young age, it has a tremendous impact," and that impact left an audible impression in his work that remains to this day.

When it came time for Snidero to make the move to college, he chose North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas), which houses one of the finest jazz programs in the world. While he had worked diligently to get there, he knew that he still had a lot more work to do once he arrived. "I was a good classical saxophonist and I entered competitions and that sort of thing" says Snidero about his pre-college years. "And when I went to North Texas, I wasn't a very good improviser. Actually, I got into the 9 O'clock band when I first went to North Texas." The bands at that institution each receive an hour designation in their title, with the One O'clock Lab Band being the most prestigious, so Snidero immediately saw where he stood and where he wanted to be, and he began doing what was necessary to get there. He continues, "Then, in the second year I was there I was in the Five O'clock Band, and then the third and fourth years I was in the One O'clock Band."

When it came time for Snidero to make the move to college, he chose North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas), which houses one of the finest jazz programs in the world. While he had worked diligently to get there, he knew that he still had a lot more work to do once he arrived. "I was a good classical saxophonist and I entered competitions and that sort of thing" says Snidero about his pre-college years. "And when I went to North Texas, I wasn't a very good improviser. Actually, I got into the 9 O'clock band when I first went to North Texas." The bands at that institution each receive an hour designation in their title, with the One O'clock Lab Band being the most prestigious, so Snidero immediately saw where he stood and where he wanted to be, and he began doing what was necessary to get there. He continues, "Then, in the second year I was there I was in the Five O'clock Band, and then the third and fourth years I was in the One O'clock Band." His rapid ascent through the ranks at North Texas was an early indicator of his potential, but he never rested on his laurels. When school was out, he continued to hone his craft during the summer(s). Snidero notes, "I met [saxophonist] Dave Liebman when I was at North Texas and I came to New York during the summertime and studied with Liebman; he was really the catalyst for me to come to New York when I did because he said that I should. And then, I studied with Liebman when I came to New York. Phil [Woods] was before North Texas and into it a little bit and Liebman was the guy that I got into at North Texas. I studied a lot of his solos. There's a group [he was in] with [drummer] Elvin Jones, and they did a record called Live At The Lighthouse (Blue Note, 1972) that was very popular when I was a student. We used to listen to that record, in particular, a lot. And I played a lot of soprano back then and I saw Liebman play." That clearly inspired Snidero. He continues, "[Liebman] kind of took over that mentorship that I had with Phil. Then, when I came to New York, I had that kind of connection that helped me to get here."

Snidero arrived in New York in 1981 and it didn't take him long to find his way; within a year's time he was sharing the bandstand with organist Jack McDuff. Looking back on how his first big break came to be, Snidero notes, "Someone that I met in New York was playing with Brother Jack McDuff, and he was out of town for a time. So, I got a call from Jack in the afternoon one day, and he said, 'Can you come to the recording studio right now?' I was 23 years old, so I say 'yeah, yeah,' and he asked me if I had ever played funk before, which I really hadn't; at least, probably not what he meant, but I lied and I said 'yeah.' Then I took out a David Sanborn record that I had and listened to some of that before I split, but it turned out, when I got to the recording studio he wanted me to just play jazz. It was just basically over straight eighth notes. Then he hired me for the band. That was in 1982. I came [to New York] in the Fall of '81 and I started playing with Jack in the beginning of '82."

With McDuff, Snidero became a road warrior for a spell and learned the ins-and-outs of the musician's life. He notes, "We toured the country; we criss-crossed back and forth two or three times. I really felt like I was going to graduate school. It really had that feeling because there was no way that I was going to learn what I was learning from Jack in school, as far as playing every night with guys that had such great time and are very professional and polished. We were climbing in the van and driving four hours and doing the same thing [night after night]. I think, in a year, we had about 150 gigs."

While Snidero was being indoctrinated in the ways of the touring musician, he was also getting invaluable experience in the studio. He notes, "That was a great, great experience with Jack. I did three recordings, which was really unusual then. You have to understand that jazz, at that point, had really just bottomed out. The thing that was really the catalyst for a new scene was Wynton [Marsalis]. Marsalis coming on the scene and playing with Blakey, and playing with Herbie [Hancock]'s group, and making a record for Columbia was important. He was the first guy of our age that we could point to that was getting a lot of press. Right when I started to play with Jack was kind of right at that time, and things had just bottomed out, so doing three records at that time wasn't that easy. There wasn't a lot of major label recording activity." He rightly states that "to have that gig with Brother Jack McDuff and to do those records at that time was pretty prestigious, and it meant something."

As word of Snidero's skills spread, other leaders brought him aboard. Associations with the Mingus Big Band and saxophone legend Frank Wess developed, but one of the most important sideman jobs Snidero took early on was with pianist Toshiko Akiyoshi's Jazz Orchestra. His connection to Akiyoshi would ultimately help him launch his solo career, but this relationship almost never happened; Snidero wasn't sure if he could handle the job at first. He recalls, "[Akiyoshi's husband/partner, saxophonist] Lew [Tabackin] had called me to play in the band in 1983, and I said I hadn't been playing my doubles. I didn't think I could do it. So I said that maybe I shouldn't make the rehearsal he was talking about. I didn't turn it down, so to speak, but I didn't think I was qualified; I had not been playing flute and I was not a good clarinetist. He said 'ok,' but then he called me back a couple of weeks later, and he said, 'just come down.' So, I did."

Snidero's experiences with this group proved to be another highlight of his early years in New York. He notes, "I had a lot of respect for them and a lot of respect for the music, which was very hard. I felt it was a great opportunity for me because, first off, it just took me into a whole other audience. They were touring in Japan, they were playing a lot of concert halls in the states. We played at Carnegie Hall, probably three times. As a matter of fact, we played in Carnegie Hall in 1983." That concert, as Snidero tells it, proved to be a pivotal moment in his career. He states, "Toshiko was producing records for EMI Japan, and after that concert, she asked me if I would want to do a record with that label." That was the beginning of Snidero's leader-on-record life.

On Time (Toshiba EMI, 1984) found Snidero in good company making great music under his own name for the first time. Trumpeter Brian Lynch, Snidero's good friend and band mate from the Akiyoshi group, came on board, and both young horn players found themselves in the midst of rhythmic greatness. Snidero explains, "So we did this record, and I was scared shitless! I was so scared. It was Kenny Kirkland [on piano] and it was just unbelievable. George Mraz [on bass]; and Billy Hart on drums; and Brian [Lynch]. We did it at Rudy Van Gelder's studio, so the whole thing was scary, but it came out pretty good." "Pretty good" is actually a bit of an understatement, but humility tends to shade most of Snidero's thoughts on his own work.

In looking back on his early sideman stints and his initial foray(s) into recording, Snidero states, "That was a really great time. We weren't making a lot of money or anything like that, but we were playing a lot. We were just trying to play as well as we could, and figure out what was cool, and what was hip, and what was musical, and who we wanted to be as musicians." That act of self-discovery continued as Snidero built up his discography. His sophomore release—Mixed Bag (Criss Cross, 1987)—came three years after On Time, and a string of albums on small(er) labels like the Dutch Criss Cross imprint and Italian Red label followed. On most of these dates, like the highly praised Blue Afternoon (Criss Cross, 1989) and the lesser-known Storm Rising (Ken Music, 1990), Snidero emphasized his original music, but sprinkled in some choice standards. His focused and friendly horn was out front on these quartet and quintet outings which featured many of his peers, like Lynch, bassist Peter Washington, and pianist Benny Green.

The '80s proved to be a fruitful time in Snidero's career, as he learned from the best and began to blaze his own trail, but the '90s was all about branching out and moving on. He ended his association with Criss Cross and Red during this decade, authored a series of successful jazz books, stood shoulder-to-shoulder with one of the greatest voices in history, and produced a pair of well-regarded, concept-driven albums as the millennium drew to a close. He looks back on most of those experiences with a sense of pride about what came to pass, but he also readily acknowledges the struggles he faced with his own work. Snidero's quick to say that he felt "stagnant" because he wasn't writing much, but he's even quicker in pointing out the positives from this period. He notes, "the time that I spent with Frank Sinatra—which was '90 to '95—was just another completely mind-blowing experience. I'll treasure those years as much as anything because it's really rare to have an opportunity to be near someone that performs with that amount of purity and genius and artistic talent. It was just unbelievable to be around that, and those were some really happy times. I guess, what I'm saying is that for me, the '90s was a time where I wasn't really thinking about myself as a leader per se, and developing my own music as a composer, until the book thing came around. I wrote those [Jazz Conception books] in '96. They brought out a completely different side of me that I had been tinkering with, starting in the late '80s, as someone who did clinics. [Back then,] I began an association with the Selmer company and I formulated something; a conception about how I taught jazz, and what I thought was effective, and what I thought was needed."

The key word in that whole statement is "needed." In a market crowded with lick-based books and lead sheet-driven products, Snidero managed to make an impact with something a little different that tapped into idiomatic language and phrasing that students need to be exposed to. These books became a huge success, eventually spawning an "Easy" and "Intermediate" series that filled in the gaps for players at different levels. To date, the Jazz Conception series contains over forty books, and it remains one of the most popular jazz education resources out there. In looking back with a then-to-now telescope, Snidero notes, "I knew that if I got it right that it was going to be successful, but I didn't know just how successful it would become."

While Snidero speaks of compositional stagnancy as a leader-on-record during this period, this writing lull didn't stop him from making some significant artistic statements; he delivered his only all-standards album to date—Standards+Plus (Double-Time, 1997)—and a record dedicated to one of jazz's great saxophone icons—The Music Of Joe Henderson (Double Time Records, 2000)— during this period. Then, as the new millennium was getting underway, Snidero's composer juices began to flow again and the time seemed right to explore the world of saxophone-and-strings.

In some respects, Snidero was following in the footsteps of his saxophone forefathers by working in that particular area. In fact, creating a sax-with-strings statement has become a rite of passage for reed-men-of-note ever since alto saxophonist Charlie Parker did the deed, but the process usually involves bringing in an outside arranger and/or composer to set the scene. Snidero's simply-titled Strings (Milestone, 2003) stands apart because he arranged everything and wrote the majority of the music for the date. Snidero notes, "I was going to do that record for a small label and have an arranger do it, but I just couldn't bring myself to do that. I decided I was going to do it myself and just learned how to do it. I took lessons with friends or people that I knew. I got on a lot of people with questions and tried to figure out what to listen to, what my values are, and what I really liked in string writing. I wanted to avoid, for the most part, that kind of generic string pad. I really wanted it to be interactive with the quartet. So, I wrote all of that music; there are two standards, but everything else is original."

Snidero did his homework, laid the groundwork, and got set to make the record, but history and horror would intervene. He recalls, "We went to the rehearsal, and that rehearsal was on September 10, 2001. And the record date was scheduled for September 11, 2001. 9/11. And so, we got up in the morning. The bassist lives in the same building I live in; we live in Manhattan, so we got on the train. The recording studio was in Brooklyn and we came over top—in Brooklyn, the train's elevated—and there are the buildings on fire. It was the hardest day." He continues, "So, obviously the date was cancelled. I had built up a whole year's worth of really, really hard work to that moment; I hired the musicians; I was the contractor; I'd done everything. We had to cancel it. So we had to kind of regroup, and then we did it a couple months later. But I have to say, it's a better record [than it would have been] because it did give me two months to work on the music some more. It's definitely a better record than it could have been if we had recorded it on 9/11."

The record, which features 10 string players and a jazz quartet comprised of Snidero, pianist Renee Rosnes, bassist Paul Gill and drummer Billy Drummond, proved to be an artistic and critical success. Snidero notes, "It came out on Milestone [Records], so I was really, really, happy about that. A lot of people have said wonderful things about it and it's definitely one of my works that I'm most proud of."

Snidero put out one more record on Milestone—Close Up (Milestone, 2004), featuring tenor saxophonist Eric Alexander—before finding his way to the Savant label, which he's happily called home since 2007. Snidero elaborates, "I have to say that my association with Savant has been tremendous. It's just a great record company. Joe and Barney Fields leave it up to you with what you want to do; it's got to be good, and they're not going to take anything less than great actually, but they let you do what you want to do and I've really been happy about that association. Now it's going on 6 years, and this is my fourth recording for Savant. That's the most records I've done for any label."

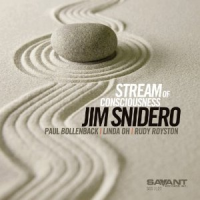

The Savant albums, as of this interview, go from the organ-centric Tippin' (Savant, 2007) to the powerful-and-wondrous Stream Of Consciousness (Savant, 2013). Snidero recalls how his association with the label began: "I was working with [guitarist] Paul Bollenback a lot, and with [pianist/organist] Mike LeDonne, who's another friend of mine that I've known for 30 years. I've learned a tremendous amount from him, and he's a fantastic musician. I worked a lot with him at [New York's ] Smoke, with the organ group on Tuesday nights, and Paul had been doing that, so that was the genesis of the first Savant date—Tippin'. And drummer Tony Reedus was on that record; another longtime friend who died 4 years ago. So that band was a working band up at Smoke. I was subbing for Eric Alexander up there, but I was up there a lot. So, we just went into the studio, and Mike actually introduced me to Joe Fields [of Savant]."

Each of the three albums that followed Tippin' has its own identity, but they're all bound together by the presence of guitar. "I hate to use the word 'different'" Snidero says, regarding his decision to remove piano/organ from the equation and stick with guitar, "but [I wanted] something that would put me in a different space. It started with Crossfire (Savant, 2009), and then Interface (Savant, 2011), and now this last record—Stream Of Consciousness.. One of the main reasons that I've stuck with guitar for these three records is the acoustic guitar. When I heard Paul play the acoustic guitar on Crossfire, I said 'oh, now that's what I want on the next record, and the next record' because I love the sound of that instrument; especially when he's playing it. I think it goes really well with the alto saxophone. There's something about the timbre of the alto and the acoustic guitar that really complement each other. So I wrote all the material on Interface, and four of those pieces are for acoustic guitar. And they're not all slow either; there's one tune called "Viper" that's a fast modal burner, and I have acoustic guitar on that, so I was trying to find different ways to use the acoustic guitar. I really love that sound."

Snidero's passion for the acoustic carried over onto his brilliantly bold Stream Of Consciousness, but only in a small way. He notes, "I was planning on using a little bit more acoustic guitar on this record, but in the studio we ended up switching to electric guitar on one tune that was supposed to be acoustic, and then we ended up not using one tune that we recorded [with acoustic]. There were going to be eight or nine tunes in total, with four featuring acoustic, but it turned out to only be two."

Many jazz artists tend to become more conservative as they move on down the line, changing their status from newbie to veteran, but the exact opposite seems to be happening with Snidero; Stream Of Consciousness is his most dazzlingly daring album to date. It showcases every aspect of Snidero's personality, pushes at the walls of convention, and features one of the hottest rhythm teams he's ever used. His praise for this duo—drummer Rudy Royston and bassist Linda May Han Oh—is immediate and high. With regard to Royston, he enthusiastically notes, "he's a fabulous drummer; a really amazing drummer." Of Oh he says, "Linda is really very good in a lot of ways. She's a great bassist and she's got really good ears; she's not afraid to go with the moment."

Post-bop, funk and the great beyond all bubble to the surface at one time or another, but it's that last category that really makes this record stand out. On songs like "Fear One," Snidero explores new avenues that prove to be ear-opening. He notes, "I had started experimenting with having different tonalities going on at one time, and "Fear One" is really something that [came out of that]. That concept is something that I'm going to explore more in the future. The band is in two keys the entire time. There's no bass on it, but when we've been playing it live, I've had the bassist playing. Linda did it when we did it in New York but, for the record, I wanted it a little bit more open. I had Paul playing in C during the changes on the A sections; he stays on those exact chord voicings, which are "Cherokee" in C, but I'm playing in Bb the whole time. There's something about that sound. It took me a long time to decide that I wanted to have those two keys working together. Most musicians would say, 'the band's in C, but you're in Bb? How does that work!?,' but I'm telling you it works; It sounds good, and I'm not exactly sure why yet, but I'm definitely going to start experimenting with that more. I'm really interested in finding ways to stretch the limits without being overt about it. For me, I feel that if you go too far, then it's not fun to listen to anymore; it's not as interesting."

While artists are typically enthusiastic about their work as it reaches the marketplace, Snidero's positive response to this record isn't just another case of artist-driven hyperbole. He says, "I really think that Stream Of Consciousness is my best record [to date]. There's a nice flow on the record. It just feels like all of these songs are supposed to be there," and it's hard to argue with that; the critical response to this album has largely echoed these thoughts, giving him more reasons to be pleased.

Snidero's efforts to defy convention also managed to seep into his educational work in 2013. He launched The Jazz Conception Company, which explores a new frontier in the technology-meets-education world. He merged the idea of video lessons, play-alongs, lectures, blackboard learning and more, and made it all into a downloadable format, as part of a take-it-anywhere iPad App. Snidero comments on this venture: "I saw the potential of the technology and how it could be used. It can really make for a richer educational experience. I realized that you could create this multimedia platform that, if used in the proper way, can really bring clarity to a lot of aspects of the music all at once. When you're looking at someone playing, that in itself is pretty powerful. But then, you're also able to switch back and forth and have the functionality where you can go to the music, and keep watching, and keep listening; this kind of interactive functionality is really seamless. It really is an innovative app. The web-based system works just as well. It's a little less sophisticated, but it still works really well. The app is really amazing. It's very fast, and it's very smooth. And of course, after the initial download, you're not tethered to the internet. When I realized that, I thought that this is something that I've really got to explore. It's got the potential to bring tremendous content to anybody in the world that's got a credit card and wants to subscribe to it for a year. Yes, they have to have an iPad if they don't want to be tethered to the internet, but I think that that's absolutely the way of the future, and if you have an iPad, you can study this thing anytime, anywhere. I think it's way ahead of the curve in that way."

Snidero embraces all that technology has to offer in music education and, while he's quick to explain that this model is different from other trending forms of jazz learning, he still feels that other models have their value. When asked about Skype lessons as a comparative form of learning, Snidero comments, "Skype lessons are good; any kind of lessons are good, but I really wanted to present a course. It's not like three or four lessons. If you're talking about the jazz improvisation course, it can last. It's sequential and it makes sense sequentially. Each lesson builds on the lesson before, and somebody has an entire year to absorb all of this information."

Snidero's varied ventures mark him as one of the few, true, three-hundred-and-sixty degree jazz men, working at every aspect of the music from education to performance to business and beyond. Over the course of the last several decades, the student has truly become the master; Jim Snidero has gone from advice-taker to taste-maker.

< Previous

Fortunate Action

Next >

Dedications, Vol. II

Comments

About Jim Snidero

Instrument: Saxophone, alto

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

Jim Snidero

Interview

Dan Bilawsky

United States

New York

New York City

Phil Woods

Dave Liebman

Elvin Jones

Jack McDuff

David Sanborn

Frank Wess

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Brian Lynch

Kenny Kirkland

George Mraz

Billy Hart

rudy van gelder

Peter Washington

Benny Green

Joe Henderson

Charlie Parker

Renee Rosnes

Paul Gill

Billy Drummond

Eric Alexander

Paul Bollenback

Mike LeDonne

Tony Reedus

Rudy Royston

Linda Oh

Concerts

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.