Home » Jazz Articles » Live Review » Francois Bourassa: Quid Pro Piano

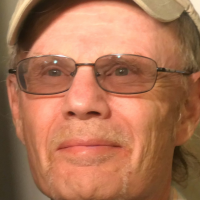

Francois Bourassa: Quid Pro Piano

2010 Festival International de Jazz de Montréal

Chapelle historique du Bon-Pasteur

Montreal, Canada

June 30, 2010

When pianist/composer Francois Bourassa performed in the mid-1980s at the Montreal International Jazz Festival, the sound he produced registered like a doubled-up fist of angry, aggressive music that, stylistically, recalled attack dog pugilist Roberto Duran, when he was at his bellicose best.

And then, a chance encounter in 2008, with an up-and-coming local club singer, demonstrated a complete and astounding reversal of form. Gone was the hammerhead approach to the keys, replaced by a loving touch in a supporting role, and a willingness to share his sensitive side with the world. He opened the second set with a couple of solo compositions; quasi-classical ballads that were absolute gems. The pianist proved—in a matter of two chords and a trill—that there actually are human beings out there capable of morphing into (and embracing) their opposite, which, in the context of an evolving performing artist, is a development to be feted.

So how do we account for Bourassa's "simply marvelous" metamorphosis?

François Bourassa is the son of former Québec Premier Robert Bourassa (1933-1996), who was a political lightning rod for controversy. François, the son, loved and worshipped his famous father, who was in equal parts adored and detested for the contentious decisions he underwrote concerning the highly volatile relationship between French- and English-speaking Québec.

Naturally, as a young boy, he would have lacked the cognitive maturity to understand why others didn't feel as he did. During his formative years, he was constantly exposed to criticism—and even hatred—of his divisive father, and what he believed were lies that stung to the core of his being, as well as hurtful comments directed to him personally. To protect himself and his love for his revered father, he was obliged to grow a thick skin that evolved into an impenetrable carapace, which provided both comfort and immunity against the abuse and censure all politicians must abide. As he was discovering and developing his formidable gifts as a musician, the music, perforce, reflected not only the kind of person he had become, but the extension of an ideal self—someone who could not only play through a punch that has hurt him but counterpoint back. From here on in, it would take the better part of twenty years for François Bourassa to learn how to become himself instead of his father's son.

After winning the New Talent Prize at the 1985 Festival International de Jazz de Montréal, the François Bourassa Trio recorded three albums. Almost without exception, the music reprises that theme of lashing out at the world via aggressive, avenging and marauding compositions that refuse to recognize—much less give voice to—his softer side. The Bourassa encountered in his late twenties was feeling good about himself in the fortress around his heart, but was unaware that he had condemned himself to the equivalent of an emotional straightjacket which severely restricted his range both as a performer and composer.

Twenty years hence, François Bourassa's fists are unclenched; an artist for whom the piano is no longer a lethal weapon, but an instrument made to serve the repertoire of the heart. He is now, along with John Stetch, regarded as one of Canada's finest modern jazz composer-pianists.

During a 2010 Montreal Jazz Festival concert that took place at the Chapelle historique du Bon-Pasteur, the 2007 recipient of the Oscar Peterson Award decided on an original playlist that seamlessly integrated classical and jazz. Some of the pieces were improvisations intended for film; another section belonged to an oratorio; others were personal. What was signature in them all were the arrestingly original, gunnysack-stitched chord progressions that, with a nod to Rachmaninoff, drew out the unparalleled physicality and sumptuousness of sound of the piano on one hand and, at the other extreme, minimalist chords that tingled like a child's crib bells. Here was a musician in total control of his craft, who could give himself completely over to the development and shaping of his ideas. Listeners under the spell of the music wouldn't have been aware or concerned if it were jazz or classical on the page, so cross-thatched were they.

The jazz element came to the fore when the pianist found a groove played by mostly the left but sometimes the right hand, leaving the free hand free to improvise. Duly noted was the novelty and difficulty in executing a right hand groove, left hand improv. Most jazz pianists aren't technically capable of pulling it off, much less able to conceptually articulate the feeling that compels the technique. Left hand improvisations, especially in the deep end, invariably evoke uncertainty, indecision and ambiguity.

And just as suddenly and purposefully, the groove would morph into a strikingly original but highly formalized classical sequence where there was no settling into a delineated space other than that defined by perpetual invention, like Bach, or Mozart. It wasn't always clear where the work—or a particular section of the work under consideration—was going, but at the end of the day Bourassa left no doubt that he is a serious and significant composer who has all the tools—exquisite touch, effortless right hand left hand independence—to satisfy the most complex demands of a quick and fertile imagination.

And just as suddenly and purposefully, the groove would morph into a strikingly original but highly formalized classical sequence where there was no settling into a delineated space other than that defined by perpetual invention, like Bach, or Mozart. It wasn't always clear where the work—or a particular section of the work under consideration—was going, but at the end of the day Bourassa left no doubt that he is a serious and significant composer who has all the tools—exquisite touch, effortless right hand left hand independence—to satisfy the most complex demands of a quick and fertile imagination. Since both classical and jazz enthusiasts are fiercely devoted to their preferred genre, Bourassa's most pressing challenge is to fashion appreciative audiences equal to the demands of his distinctly original classical-jazz fusion. At the behest of an irrepressibly creative musical mind, Bourassa has dared to go where the less madly inspired have feared to tread. In consideration of the inevitable lag between listeners and any brave new musical form, the composer might consider staying with his exquisitely gorgeous and architecturally more accessible shorter pieces, allowing audiences to ease their way into the interval and invention that is François Bourassa.

Photo Credit

Denis Beaumont

This article first appeared in Arts and Opinion

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.