Home » Jazz Articles » Journey into Jazz » Teach A Man To Phish

Teach A Man To Phish

The jam band audience wants every show to be unique. If you’re playing in the jam band scene you can’t play the same set ever. [...] That community wants to be a part of something different and they’ll come every night.

—Eric Krasno

Conversations with Billy Martin and John Medeski (both from Medeski Martin & Wood), Eric Krasno of Soulive, Jack Stratton of Vulfpeck and Peter Apfelbaum helped me see how jam bands are, and aren't, like other improvising musical organisms. All of them have spent some time spreading jam.

From these conversations, I gathered that while jam bands share some musical conventions, their defining element is the audience. Jam band fans are deeply engaged, coming with their own set of expectations and criteria. Whether those expectations were a byproduct of the music or the fans is still up for debate.

Krasno told me "The jam band audience wants every show to be unique. If you're playing in the jam band scene you can't play the same set ever. [...] That community wants to be a part of something different and they'll come every night."

Medeski told me that his band had not actively sought out a jam band audience. He said that a lot of their early success in the jam band universe "had to do with the band Phish, playing our CD every night on tour, people wondering what it was. They were the first influencers."

At the same time, he was adamant that they didn't chase after any particular audience or change what they did:

"We didn't inherit the audience, we were part of the creation of that audience. Phish was out there and we were doing it at smaller places [...] We improvised a lot and we never played the same set twice, ever. It had nothing to do with 'that's what you're supposed to do.' That's what we did for us. And I think Phish did it too."

When it comes to loyal fans—those who identify as part of a tribe—few are as devoted as Phishheads. The band, formed in Burlington, VT in 1983, has amassed a vast body of work. Like the Grateful Dead before them, they tour relentlessly and inspire fans to count shows attended, catalog song performances, trade arcana like currency, and debate every musical move.

Jack Stratton compared meeting Phish guitarist Trey Anastasio to meeting a guru. He told me Trey has "Baba Ram Dass"-level presence when you actually meet him. It's the real deal, you know, which is a metaphor for them as a band because they're a live band. It's all about live. They were just having fun. The way he tells the story, fan bases become their own thing at a certain point."

If you're a fan, all of this might seem obvious, or painfully reductive. But for the uninitiated, it's hard to overstate: Phish is not just a band. It's a way of life, a worldview, maybe even a cult or a religion built around music.

And, in keeping with the great Marx Brothers tradition of not wanting to belong to any club that would have me as a member, I've avoided it for 30 years, with one exception: in 1996, I saw Phish perform in London.

My cousin, a fan, was "on tour" with them through Europe that summer—meaning he followed the band from city to city, took communion with them nightly, paid close attention, and perhaps sold bracelets or empanadas in the parking lot before the show.

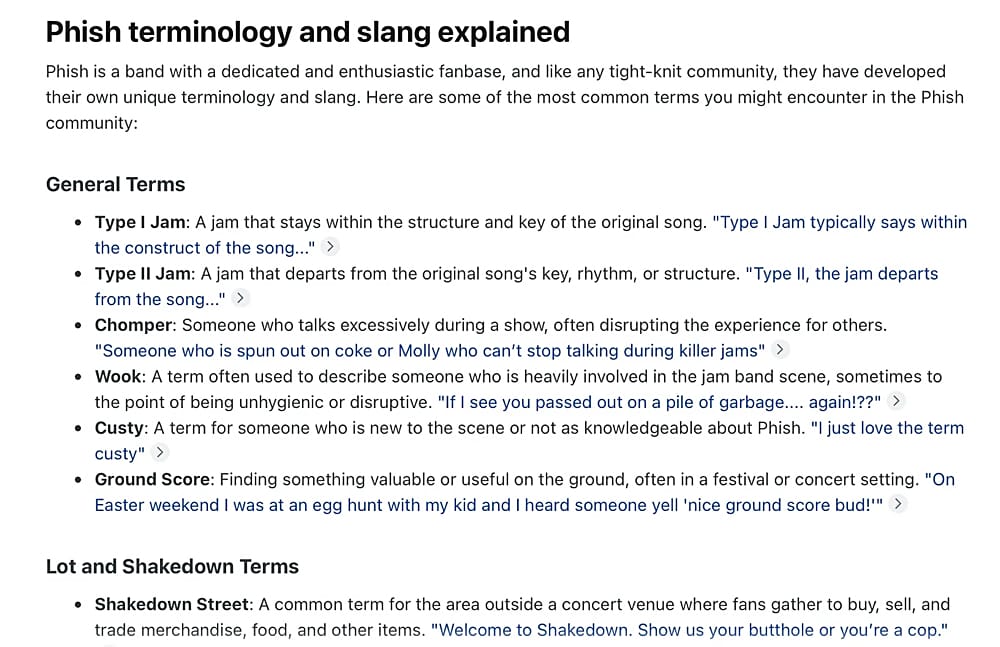

This isn't called tailgating. It's called "Shakedown Street," itself a reference to a Grateful Dead album. That naming convention and self referencing is part of Phishadelia. Everything has a term, a taxonomy, as seen in this Glossary of Phish terms or this Phish Terminology Explainer.

During the summer of '96, while interning at MTV in London, I got a call from security: someone claiming to be my cousin was at the front gate and he looked a little questionable. He had rolled into town with Phish, looking like he'd been wandering the desert for 40 days: tie-dye shirt, long hair, scruffy shorts, hemp accessories. That night, he took me to see his phavorite band. On the way to the show we bought what turned out to be a bag of oregano on Camden High Street.

I remember little about the show, but I recall how American the crowd felt because the majority of the audience was made up of kids like my cousin who had been following the band from country to country. I noticed how tribal the atmosphere was, reminiscent of being at Jewish sleep away camp. And that was not a coincidence.

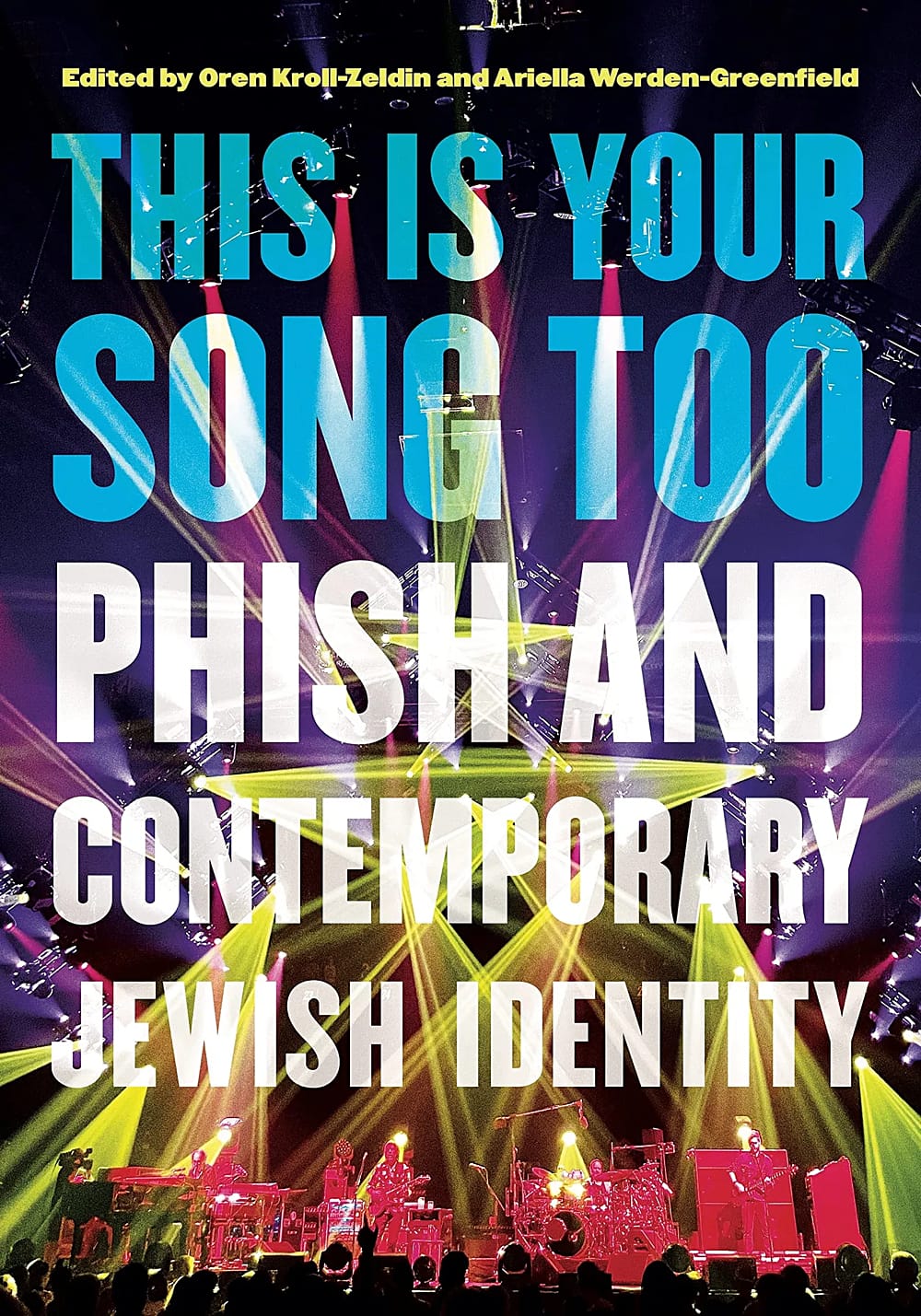

A book called This Is Your Song Too has sat on my nightstand for a year. It's a collection of essays about the Jewishness of Phish, a theme that's hard to ignore. The book describes how many people first discovered the band at Jewish summer camp, and helps to outline the layers of commentary, the coded language, and ritual around the band that feel almost Talmudic. It's a shared culture of ecstatic analysis.

This kind of intense devotion used to exhaust me. But lately, I've tried to stay open, to not calcify into old habits. Maybe it's middle age, maybe it's the chaos of the world. I've thought about getting a tattoo, taking dance lessons, and seeing Phish.

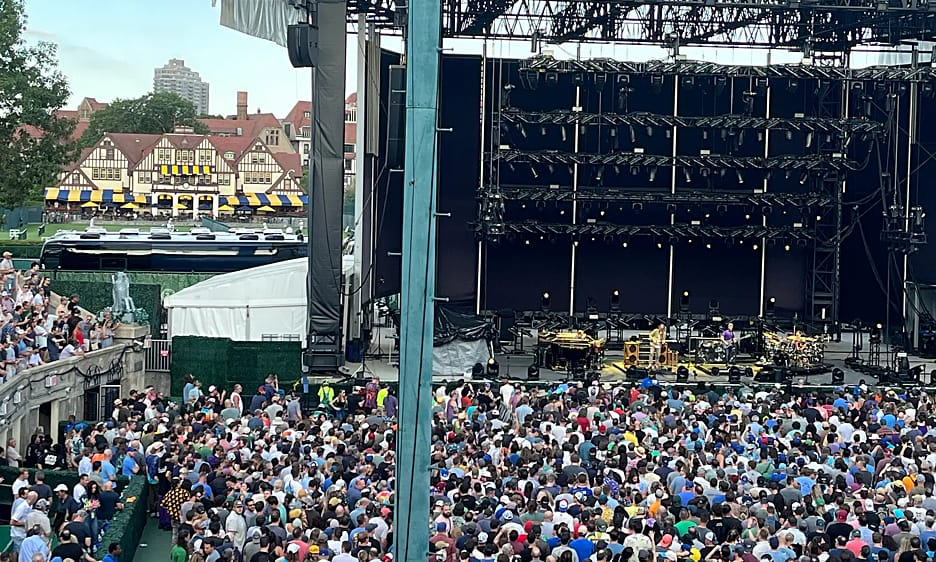

Herbie, an old college friend and devoted Phish fan, offered to take me. "One night won't be enough," he said, and bought us good seats for both nights at Forest Hills.

I wrote to him:

"I will do my best to keep an open mind, open heart and open ears. I suppose the question is—what will it mean to me, as a 48-year-old, unfamiliar with all the jargon, history, inside info? Will it feel like more than a concert? Will I be a witness or a participant? Can I allow myself to belong to a club that WILL have me as a member?"

Looking at that now, I realize that was the right question. Witness or participant?

I decided that if I was going to do this, I should take notes and maybe write about it later. But I also decided to take mushrooms to fully experience it.

And that's what I did. I took mushrooms, and I took notes. Full immersion. Full gonzo.

Read on to find out what happened.

The ten-minute walk from the train to Forest Hills Stadium feels like crossing into an alternate reality. There is no "Shakedown Street" here (we knew this going in from an email we received earlier in the day: "There's no parking lot or room outside for a traditional lot scene"), but the telltale hiss of nitrous balloons is unmistakable. "The Nitrous Mafia," Herbie says. "They're aggressive here." It sounds like a Slytherin crime syndicate to me but it's just one in a long list of new terms to learn.

Inside, we find our seats. The crowd is mostly white, mostly male, mostly kind. The guy next to us quizzes Herbie on his show count ("More than 70, less than 100"), and whether he'd been to Playa del Mar in Mexico to see the band (Herbie had). They play Jewish Geography and compare experiences.

In anticipation, people around us buzz about what they hope to hear tonight. "I want 'Tweezer'! a guy behind us yells, referencing a song the band hadn't yet played on this tour.

Phish takes the stage nonchalantly. They look at each other for a few seconds and reach a consensus about what to play. The music starts and 14,000 people immediately begin dancing in joyous, fluid synchronization, like some mutually agreed upon form of hypnosis.

"This is 'The Moma Dance,'" says Herbie.

I start taking notes:

The show started at 6:30pm because the band will play for nearly four hours and there's a strict 10pm curfew. But even in the light of day, the stage lights are clearly a huge aspect of what's happening. It's said that the band makes no setlist—they have a loose idea of what they'll play, but they really let it happen on stage. So the lighting guy, Chris Kuroda, who has been with Phish since 1989 and is sometimes called the fifth member of the band (so says Herbie), has to improvise and follow the energy closely.

There is a pervasive sense of positivity in the audience. It's all very civilized. Forest Hills Stadium is a pretty cushy spot, designed for tennis, and surrounded by buildings that would be more expected in the Swiss Alps than in Queens. Late afternoon matches are underway on the tennis courts behind the stage, like something out of Wes Anderson or The Simpsons. Do they hear the music out on the courts? Does any of this seem strange to them?

"I know how to play this on guitar," says Herbie as the band starts into "Stash." I realize how intimately fans know this music, gear setups, favorite venues, inside jokes. Phish is its own world, built on shared codes.

By set break, the mushrooms are taking effect.

Set two starts while we are out of our seats and we don't notice that the music has begun again because of the remarkable acoustic design of the stadium (a concession to the neighbors in Forest Hills).

When we return to our seats, the band is mid-jam on "Carini." It is exactly what I'd imagined Phish would sound like and I dig it. "People like it when expectations are met," Herbie said. And Phish fans have many expectations.

Later I will learn that this is "the longest performance of the song in the band's history." (It is this kind of relentless note taking by the Phish community that has made me wary, but I won't deny that it is impressive.)

It's one of the most earnest, un-ironic experiences I've had in years. Around us, advanced Phishheads seem to guide the energy. One dances like he's conducting the band. He looks like Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Chad Smith's hippy younger brother. Actually, 25% of the crowd looks like Chad Smith's brother.

"It's so Jewish," I say to Herbie. A woman in front of me overhears and turns around mid-shimmy, smiling. "Why?" she asks.

"It's Talmudic," I explain. "Layered commentary, ecstatic ritual, questions that matter as much as answers, commentary as important as the source material." She nods and keeps dancing.

I start tripping. The sun is down now, and the band appears to hover in space, suspended right in front of me in what looks to be a small light box. They remind me of little wind-up dolls in a glowing diorama. And I think: as a performer, your insecurities are irrelevant. You're there to be witnessed, not to apologize.

I write: Why am I incapable of doing something just for the sake of it? I went to Phish, but I couldn't help assigning myself homework. It's not enough to just experience it? Or maybe this insight is the experience.

When they launch into "Tweezer," the guys behind us lose their minds.

When they start in on "Harry Hood." Herbie leans over: "This will be great."

I write: At a certain point you just decide to put yourself in their hands. There is something generous about it. The band will provide the space for you to go inward. They'll guide you through the experience if you want.

I'm not saying that they're better than other bands. But most bands could stand to see this—the group commitment is insane, the telepathy, the focus, the acceptance.

Eventually, you conclude: you don't have to explain yourself all the time.

It's not that important.

What you think is not so important.

What you do is not that important.

It's okay.

By the end, Herbie and I are both crying a little. "That," he says, "is what 'Harry Hood' is all about."

When the band comes out for their encore, Herbie declares "they will have to play 'Tweezer Reprise.'"

I turn to him: "I don't want to come back tomorrow. There's no way to repeat this experience."

But we do go back.

Night 2

Same seats, same people around us, new setlist. This time: no mushrooms, just THC and mezcal. "Make it about the music tonight," I tell myself.They open with "Free." I start free associating, thinking about jazz.

Jazz once revolved around a common repertoire, shared among musicians. I interviewed the late sociologist Howard Becker about his book Do You Know... (co-written with Robert R. Faulkner) in which they talked about how repertoire was the common currency of jazz music for years. Know the songs to know the music. The vocabulary was found in the songs themselves.

A consequence of so much jazz education today is that the audience is very informed, which in turn affects the music. Musicians make more complex music to please an overeducated audience, which distances the music from its original roots in dancing, and in turn from a larger audience.

Pianist Fred Hersch outlined this when I talked to him years ago: "The growth of the jazz education industry is twofold. It builds audiences... It's great that there's a lot of information but having a lot of information is like having a big vocabulary with no story to tell... jazz music is now a little bit in danger of backing itself into the same kind of corner that contemporary composition backed itself into when people were writing rather severe stuff, where you could pick it apart on paper."

Phish on the other hand may suffer from an inverse affliction—the audience is generally very educated and deeply engaged but prone to over analysis of music that is not necessarily so complicated in the first place. They parse every note and every set as if taking dictation, looking for source code to help explain the ineffable feeling in the music, which is ultimately made for dancing!

Still, I am very moved by how locked in both band and audience are—the music is not difficult but it does unfold in real time and is improvised. I can't remember a time when I have seen so many people so euphoric about largely instrumental music. It demands focus and attention but also encourages abandon and surrender. It's tantric.

Overall, I take fewer notes on the second night. "Fewer insights?" Herbie asks. "Or just listening?"

"Both," I reply.

I conclude that the mushrooms must have played a significant part in the revelations of the first night. But it wasn't just the mushrooms. It was the marriage of the music and the mushrooms. Still, I decide, the fans are like mushrooms themselves—they don't make the music, but they alter the experience.

As a jam unfolds late into the second set, the guy behind me yells, "Bring it home!" When will we know when it is home, I wonder? It will reveal itself. This is the unspoken agreement, Phish will always bring it home as long as you are there to receive it.

As we funnel out of the stadium, the crowd compresses in that anxious, shoulder-to-shoulder way large groups tend to do. And yet, I feel calm. Surrounded by thousands of strangers—many of whom I am sure are surgeons, lawyers, therapists, people who own boats—I trust we'll collectively find the way. We emerge from the crush, past the Nitrous Mafia, and descend into the subway, gently returning to real life.

We bring ourselves home.

Today, nearly a week later, I ask myself what any of it meant. I may need to go to another show in order to fully understand it.

Tags

Journey into Jazz

Phish

Leo Sidran

Billy Martin

John Medeski

Medeski Martin and Wood

Eric Krasno

Soulive

Jack Stratton

Vulfpeck

Peter Apfelbaum

The Grateful Dead

Trey Anastasio

Fred Hersch

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.