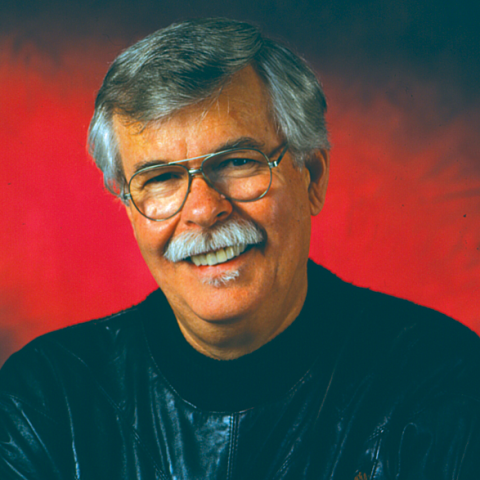

Boston trumpeter and educator Herb Pomeroy was known largely for his big band work as a leader and sideman. But in the early 2000s, Pomeroy led a gorgeous, romantic working trio consisting of Pomeroy on trumpet, Anthony Weller on guitar and David Landoni on bass. The group recorded three albums—two live and one in the studio. Live At Cafe Beaujolais in Gloucester, Mass., was their first in 1999, followed by Aluminum Baby recorded in Boston in 2003 and then Live at 75 Chestnut in Boston later that same year. Pomeroy died in August 2007.

Live At Cafe Beaujolais is a quiet album consisting largely of ballads. These include A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing, How Deep Is the Ocean, Blood Count, African Flower and Stella by Starlight. Pomeroy, who plays a muted horn on many of the tracks, is enveloped by Anthony's pretty notes and Landoni's robust bass. Even songs that spring into a medium tempo with Pomeroy on an open bell are relaxed. Without the hounding of drums and piano, there's a laid back feel, as if the three musicians are moving slowly along a park path in conversation.

Aluminum Baby features Pomeroy in a Chet Baker groove. His trumpet has a wandering, melodic feel with Anthony's guitar churning away rhythmically and ringing on solos with a Jim Hall quality. Landoni's bass does double duty—running lines and keeping solid time in place of the drum. Among the standouts are Bill Mays's Play Song, Anthony's spirited Banana Boat and Jaki Byard's Aluminum Baby. And Johnny Mandel's Emily, of course, which can't miss with a trio like this one.

Live at 75 Chestnut was Pomeroy's last album and it's the trio's best. It was a collection of standards, including My One and Only Love, Skylark, I Hear a Rhapsody and What'll I Do? All feature Anthony taking the lead and glowing on each track. Body and Soul is sensational at mid-tempo and done in a way that's new and fresh.

I had a chance to catch up with Anthony Weller...

JazzWax: How did this trio come together?

Anthony Weller: As is often the case, the gig preceded the group.

JW: How so?

AW: In the summer of 1993, I was playing a duo gig two nights a week in Gloucester, Mass., at a fine and large French-style wine bar and bistro—the Au Beaujolais. My colleague on the gig was a marvelous trombonist and pianist, Phil Swanson. He was busy getting his doctorate in composition from Boston’s New England Conservatory.

JW: Just the two of you?

AW: Eventually we were joined on the regular gig by Mike Rossi, a powerful reed player from Florida who also was getting his doctorate at the NEC. Mike’s now head of the jazz department at the University of Capetown, South Africa.

JW: How did Herb Pomeroy fit in?

AW: The proprietor and manager of the Au Beaujolais, David Amaral, had the idea to have Herb to join us one night a week. Herb was then in retirement from teaching at Boston's Berklee College of Music. He had returned to Gloucester, where he’d grown up and knew everybody. He liked to say that he’d dropped out of Harvard to go on the road with Charlie Parker and play bebop. His father and grandfather had been local dentists. Herb always had problems with his teeth.

JW: What happened to the club?

AW: A few months later, Au Beaujolais folded and reopened several blocks away on Main Street as the Café Beaujolais. The idea of a Herb Pomeroy Trio seemed appropriate. Herb already had a working trio, built around the pianist Paul Schmeling and Herb's long-time bassist John Repucci. Our trio, however, was built around my guitar and one of New England’s busiest young bassists, David Landoni. We had a steady gig and a following every other Tuesday. On the off weeks we rehearsed. [Photo above of Anthony Weller with Maggie Galloway]

JW: What kind of rehearsals?

AW: They were held at my house in Gloucester or at David Landoni's flat in Danvers, Mass. They lasted about two hours each and were a vast learning experience. My approach was to apply classical-guitar techniques, which I had in droves, to a small-band situation.

JW: Pomeroy sounds as if he was ready for something laid back.

AW: He was. We soon realized he was sick of the bombast of big bands and longed for the gentler detail-work of a small group. No detail escaped his exact ear. At the time, I was a good guitarist, but I hadn’t yet found my jazz voice. Herb was my first experience of applying the same rigor I’d found in classical music to jazz. He wanted perfection and, being a teacher through and through, he was going to get it.

JW: So you guys would just go over the material again and again?

AW: The point of the rehearsals was not just to fine-tune difficult moments in the arrangements. For example, David wrote complex trio settings of standards, as in But Not For Me, which applies Coltrane-type harmonies to Gershwin. We also went over difficult passages for improvisation. It was very encouraging that even somebody as knowledgeable as Herb still felt problem spots in his playing. We’d go round and round a difficult five measures, for example, taking turns soloing until we were no longer afraid of that part of a tune.

JW: Did the Cafe last?

AW: It eventually became the Franklin. We continued our bi-weekly gigs. It was as if we kept our little stage in the front corner, and the restaurant changed around us. David often was away, replaced most frequently by Thomas Hebb or by Bob Nieske, John Repucci or Jerry Wilfong. Meanwhile, the ever-faithful David Amaral had started managing a fine restaurant in Boston’s Beacon Hill. We played there, at 75 Chestnut, as a trio every Wednesday for about a year, with Thomas on bass.

JW: Did new players keep up with the arrangements?

AW: This constant fluctuation of personnel meant we no longer used as many of our arrangements. Each man in the trio took turns calling the next tune. Herb loved the work of Ellington and Strayhorn, of course, but he also liked to do standards in unusual keys. For example, we did Just Friends in G-flat, rather than G or F, just to work on playing in G-flat. Not surprisingly, Herb loved the blues. His blues were especially warm, nuanced, and often quite weird. This was enhanced by his use of the Harmon mute because all our venues were so small.

JW: What was your favorite?

AW: I think one of the best arrangements for the trio was Herb's version of the Count Basie chart from the 1930s called Queer Street.

JW: What did that title mean?

AW: It's a Cockney expression meaning bankrupt. Herb wrote his arrangement for trumpet, bass, and guitar from memory alone, having heard the original years earlier. It was amazing how he reduced the dense original to our three instruments.

JW: Pomeroy was a beautiful soloist.

AW: He was. He was a relentless and flexible improviser. He especially liked it when I fed him dissonant and surprising substitute chords. It gave him more to chew on, as long as they were logical. They had to be logical. I experienced this again and again when we played duos, as we often did in his last years. “We’re going to keep making music to the bitter end, and beyond,” he’d say. Between his time-weakened chops and my burgeoning primary progressive multiple sclerosis, Herb's remark was no joke.

Live At Cafe Beaujolais is a quiet album consisting largely of ballads. These include A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing, How Deep Is the Ocean, Blood Count, African Flower and Stella by Starlight. Pomeroy, who plays a muted horn on many of the tracks, is enveloped by Anthony's pretty notes and Landoni's robust bass. Even songs that spring into a medium tempo with Pomeroy on an open bell are relaxed. Without the hounding of drums and piano, there's a laid back feel, as if the three musicians are moving slowly along a park path in conversation.

Aluminum Baby features Pomeroy in a Chet Baker groove. His trumpet has a wandering, melodic feel with Anthony's guitar churning away rhythmically and ringing on solos with a Jim Hall quality. Landoni's bass does double duty—running lines and keeping solid time in place of the drum. Among the standouts are Bill Mays's Play Song, Anthony's spirited Banana Boat and Jaki Byard's Aluminum Baby. And Johnny Mandel's Emily, of course, which can't miss with a trio like this one.

Live at 75 Chestnut was Pomeroy's last album and it's the trio's best. It was a collection of standards, including My One and Only Love, Skylark, I Hear a Rhapsody and What'll I Do? All feature Anthony taking the lead and glowing on each track. Body and Soul is sensational at mid-tempo and done in a way that's new and fresh.

I had a chance to catch up with Anthony Weller...

JazzWax: How did this trio come together?

Anthony Weller: As is often the case, the gig preceded the group.

JW: How so?

AW: In the summer of 1993, I was playing a duo gig two nights a week in Gloucester, Mass., at a fine and large French-style wine bar and bistro—the Au Beaujolais. My colleague on the gig was a marvelous trombonist and pianist, Phil Swanson. He was busy getting his doctorate in composition from Boston’s New England Conservatory.

JW: Just the two of you?

AW: Eventually we were joined on the regular gig by Mike Rossi, a powerful reed player from Florida who also was getting his doctorate at the NEC. Mike’s now head of the jazz department at the University of Capetown, South Africa.

JW: How did Herb Pomeroy fit in?

AW: The proprietor and manager of the Au Beaujolais, David Amaral, had the idea to have Herb to join us one night a week. Herb was then in retirement from teaching at Boston's Berklee College of Music. He had returned to Gloucester, where he’d grown up and knew everybody. He liked to say that he’d dropped out of Harvard to go on the road with Charlie Parker and play bebop. His father and grandfather had been local dentists. Herb always had problems with his teeth.

JW: What happened to the club?

AW: A few months later, Au Beaujolais folded and reopened several blocks away on Main Street as the Café Beaujolais. The idea of a Herb Pomeroy Trio seemed appropriate. Herb already had a working trio, built around the pianist Paul Schmeling and Herb's long-time bassist John Repucci. Our trio, however, was built around my guitar and one of New England’s busiest young bassists, David Landoni. We had a steady gig and a following every other Tuesday. On the off weeks we rehearsed. [Photo above of Anthony Weller with Maggie Galloway]

JW: What kind of rehearsals?

AW: They were held at my house in Gloucester or at David Landoni's flat in Danvers, Mass. They lasted about two hours each and were a vast learning experience. My approach was to apply classical-guitar techniques, which I had in droves, to a small-band situation.

JW: Pomeroy sounds as if he was ready for something laid back.

AW: He was. We soon realized he was sick of the bombast of big bands and longed for the gentler detail-work of a small group. No detail escaped his exact ear. At the time, I was a good guitarist, but I hadn’t yet found my jazz voice. Herb was my first experience of applying the same rigor I’d found in classical music to jazz. He wanted perfection and, being a teacher through and through, he was going to get it.

JW: So you guys would just go over the material again and again?

AW: The point of the rehearsals was not just to fine-tune difficult moments in the arrangements. For example, David wrote complex trio settings of standards, as in But Not For Me, which applies Coltrane-type harmonies to Gershwin. We also went over difficult passages for improvisation. It was very encouraging that even somebody as knowledgeable as Herb still felt problem spots in his playing. We’d go round and round a difficult five measures, for example, taking turns soloing until we were no longer afraid of that part of a tune.

JW: Did the Cafe last?

AW: It eventually became the Franklin. We continued our bi-weekly gigs. It was as if we kept our little stage in the front corner, and the restaurant changed around us. David often was away, replaced most frequently by Thomas Hebb or by Bob Nieske, John Repucci or Jerry Wilfong. Meanwhile, the ever-faithful David Amaral had started managing a fine restaurant in Boston’s Beacon Hill. We played there, at 75 Chestnut, as a trio every Wednesday for about a year, with Thomas on bass.

JW: Did new players keep up with the arrangements?

AW: This constant fluctuation of personnel meant we no longer used as many of our arrangements. Each man in the trio took turns calling the next tune. Herb loved the work of Ellington and Strayhorn, of course, but he also liked to do standards in unusual keys. For example, we did Just Friends in G-flat, rather than G or F, just to work on playing in G-flat. Not surprisingly, Herb loved the blues. His blues were especially warm, nuanced, and often quite weird. This was enhanced by his use of the Harmon mute because all our venues were so small.

JW: What was your favorite?

AW: I think one of the best arrangements for the trio was Herb's version of the Count Basie chart from the 1930s called Queer Street.

JW: What did that title mean?

AW: It's a Cockney expression meaning bankrupt. Herb wrote his arrangement for trumpet, bass, and guitar from memory alone, having heard the original years earlier. It was amazing how he reduced the dense original to our three instruments.

JW: Pomeroy was a beautiful soloist.

AW: He was. He was a relentless and flexible improviser. He especially liked it when I fed him dissonant and surprising substitute chords. It gave him more to chew on, as long as they were logical. They had to be logical. I experienced this again and again when we played duos, as we often did in his last years. “We’re going to keep making music to the bitter end, and beyond,” he’d say. Between his time-weakened chops and my burgeoning primary progressive multiple sclerosis, Herb's remark was no joke.

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.