Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Anita O'Day: The Life Of A Jazz Singer

Anita O'Day: The Life Of A Jazz Singer

What is most precious about this film is the movie and television footage of O'Day singing

Anita O'Day

Anita O'Day Anita O'Day: The Life Of A Jazz Singer

AOD Productions

2008

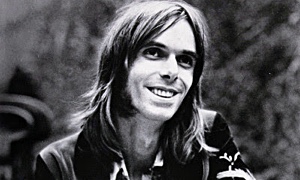

Whatever else she was, Anita O'Day was a bundle of contradictions. Though one of the top four or five women jazz singers of her generation, she had little idea what she was doing with her life or where she was going with her art. She led a miserable though long life, was regularly addicted to drugs and alcohol, frequently disappeared from view, was eventually reduced to going to the races in search of diversion, and dedicated her autobiography—High Times, Hard Times (New York, 1981), a good and honest book written with George Eells—to her dog, Emily. How do you reconcile such a life with the music? Perhaps it isn't possible.

The paradox is raised over and over again by the fast-paced documentary Anita O'Day: The Life of a Jazz Singer, directed by Robbie Cavolina and Ian McCrudden, two filmmakers with long involvement in music. The film presents O'Day's life candidly and intimately, including interviews with her as well as with numerous musicians, friends and associates. It also provides excerpts from TV interviews with Harry Reasoner, Dick Cavett, Brian Gumbo and Maury Povich. There is footage of the singer going about her daily life and appearing at clubs and concert halls. Flashes of news clippings demarcate her rise to fame—and her downfall following heroin addiction.

Out of this feast of documentation a personality emerges, a not particularly attractive or comfortable one. While her fellow singer Billie Holiday's life was equally fragmented, O'Day's does not have the same tragic sense of a beautiful person destroyed by the world around her. Rather, she comes across as female counterpart of the self-destructive trumpeter Chet Baker, who chose a life of existential chaos believing it to be a way to become "free." This confused fantasy permeates the film, which by turns lays it bare and then covers it up with rationalizations and dubious "insights."

But O'Day still deserves our love and compassion. In her own way, she was a victim of the second-class citizenship assigned both to women and to jazz entertainers during her earlier days on the circuit. She was also a victim of the drug culture that permeated the jazz life during the 1940s and 1950s. Further, there was a redemptive aspect to her singing, which was exceedingly respectful of the music and the musicians, through shared technical excellence and creativity. O'Day was a true artist of song, a musician who used her voice, rather than a mere "singer," as one of the film's interviewees points out.

Further, she was possessed of an innocent, non-religious spirituality, and told how in her youth she talked with a God who affirmed her budding identity. Throughout her life she felt an unseen, "other" presence that sustained her. Her favorite race track was Santa Anita, and one can somehow accept that Anita O'Day was a latter day saint, a Mary Magdalen, sanctified by childlike innocence, a love of the moment, and a God-given unsurpassed musical gift. In the film, at least, she never has an unkind word to say about anyone, and she seemed to be loved and accepted by those around her, even for her weaknesses. In the end, she is redeemed.

But what is most precious about this film is the movie and television footage of O'Day singing, from her very beginnings with Gene Krupa's band to studio takes during her last recording, aptly entitled Indestructible (Kayo Stereophonic, 2006). In her youth, and well into middle age, she had a naturally beautiful and expressive face that was, and remains, truly captivating.

O'Day's body language tells you much about her musical genius. Her gestures are neither seductive nor melancholic. Instead they are economical and responsive only to the music—a hand movement, a turn of the head towards a musician, a sudden freezing of motion as she holds the space between notes, a bending towards or away from the microphone, a quick change of facial expression. O'Day's whole body is attuned to the music. That is what enabled her to make the transition to bebop, which few singers fully achieved. She was in the musical moment like no other singer, hearing everything the group was doing and adding to it with spontaneity and flare.

O'Day was perhaps the only jazz singer of her generation who was capable of true improvisation, as opposed to mere scat or embellishments of the melody. And her rhythm and grasp of dynamics were as good as any instrumentalist. In one segment, she performs Jimmy Giuffre's "Four Brothers," written for Woody Herman 's 2nd Herd, with a big band, and she renders the fast-paced lead saxophone part as if she is reading it from a chart, totally in synch with the sax section. Being able to see her body respond to the nuances of the tune and the rhythm brings home the point even more. The visual clips of her singing are thrilling to watch, and the filmmakers are to be congratulated for the effort they must have put into researching, gathering and obtaining copyright releases for the film and video material.

So, how does one reconcile O'Day's musical genius with a life that was almost constantly as flat-lined as it was the time her heartbeat was stopped by a drug overdose? Perhaps you simply have to accept the split as real and irreconcilable. O'Day was as out of touch with real, everyday life as she was in touch with the music. Then again, to really swing, the jazz musician must get outside of himself or herself in order to get fully inside the musical moment. O'Day could do this because she literally threw herself away.

Anita O'Day's—or "Santa Anita's"—life could be understood as a self-sacrificial crucifix, with the horizontal bar representing her life, the vertical one being her music, and the nails being drugs, alcohol, a heroin- addicted drummer named John Poole, and a series of failed marriages. As she is portrayed in this film, and especially in singer Annie Ross' thoughtful reflections, the engaged viewer cannot help but love her and feel her pain.

Happily, O'Day's music is etched in many incomparable and enduring recordings. Ultimately, this film convinces us that, like alto saxophonist Charlie "Bird" Parker, "Anita Lives!"

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.