Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Bob Dylan: A Complete Unknown

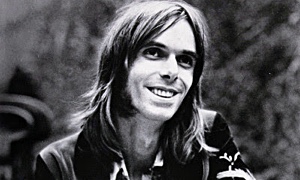

Bob Dylan: A Complete Unknown

Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan A Complete Unknown

Searchlight Pictures

2024

As with so many artistic efforts related to Bob Dylan, James Mangold's biopic A Complete Unknown may work best simply as the means to an end (and not just as inspiration to revisit the Nobel Prize winner's music). The film certainly benefits from not being taken too seriously, especially as it hardly pretends to be definitive, even in the designated 1961-1965 timeline of the screenplay by the director and Jay Cocks (based on the Elijah Wald book Dylan Goes Electric! (Dey Street Books, 2015). But it does deliver multiple epiphanies by the time its two-and-a-quarter-hour duration concludes.

For all the overheated huzzahs and nitpicking pans of the movie, it is, at its core, another in a series of cinematic contemplations of the cultural icon who may very well be a fictional character to begin with. After all, it was Robert Zimmerman from Hibbing, Minnesota who created the character of "Bob Dylan." So, while it is fair to say Mangold plays loose and free with any number of apocryphal (?) tales about the man once dubbed "the voice of a generation," the filmmaker is quite likely no more guilty of selective chronology than the subject of his work.

The fact of the matter is, Mangold knows very well how to handle larger than life figures. He dramatically elevated his profile by entering the Marvel Comics movie universe and then through participating in the latter-day Indiana Jones film franchise. It may seem somewhat odd that the director presents his main character as a fairly guileless but self-motivated songwriter and musician.

As portrayed by Timothée Chalamet (who is also one of the project's producers), Bob Dylan is clearly more interested in the creative process and its results than the widespread acclamation he may receive for his art. Therefore, this mysterious and elusive figure does not very often come right out and ask much of others here, except most significantly when it comes to his audience(s): he requires an open-mindedness he doesn't always receive.

The rapidly-evolving central figure here takes for granted affection, assistance and indeed the abuse he is offered from those he encounters. Accordingly, this account of his abject pleas to Elle Fanning's Sylvie Russo is in wild contrast to his prevalent diffidence, the impersonal likes of which he increasingly aims at those close to him, notable among which is folk music icon Pete Seeger.

Edward Norton's is a deft portrayal of that mentor-turned-father figure. Likewise, while Boyd Holbrook's enactment of Johnny Cash's is less extensive in terms of screen time, his influence on the rapidly maturing singer/songwriter/musician is arguably more profound than any others within the inner circle (except for his self-avowed hero Woody Guthrie, played with consummate restraint and sensitivity by Scoot McNairy and pictured here confined to a hospital suffering from Huntington's nerve disorder).

In contrast, Dan Fogler's alternately combative and sycophantic manager-for-hire Albert Grossman seems all too eager to ride a bandwagon: it is well to keep in mind he fostered the career of Peter, Paul and Mary to the disdain of many in the folk community also leery of Dylan's evolving musical direction. Meanwhile, Monica Barbaro's Joan Baez is the definition of no-nonsense (and with a vengeance), not just in her musical and socially conscious endeavors, but in her personal relationships.

The latter actress' performances are nothing short of startling in their emotional force, especially the concert interludes: like Chalamet's uncanny appearances singing and playing, Barbaro's are all rendered live with great aplomb and some, such as a Newport Folk duet with Dylan, involve carefully-wrought but non-musical emotional depiction of her character (in this sequence she flips her partner the bird as he stands side-stage waiting to stride out next to her).

Such high praise is certainly not to even implicitly disparage Chalamet, who has taken on roles as divergent as Willie Wonka and the main character of the grand science fiction parables of Dune (Legendary Pictures, 2021). But over the course of his now sixty-plus year career, the "real" Bob Dylan has provided much more than a mere skeletal framework for the young thespian to follow as the means to outline, then fill out the character. Sources of such information are prodigious in number.

In that regard, then, the precocious lead actor deserves the sharpest of left-handed compliments: he never succumbs to caricature in his portrayal of Dylan. His acting is actually most laudable when he is playing and singing: Chalamet delivers topical tunes such as "Masters of War" in a riveting, impassioned manner that simultaneously reminds of their continuing relevance as well as the intrinsically self-righteous attitude of the composition (it was originally composed around the time of the Cuban missile crisis in 1961).

Eschewing grand gestures, Timothée Chalamet instead uses small movements of his eyes and mouth to flesh out the most memorable moments in A Complete Unknown, usually in extreme closeups that virtually bring moviegoers right into the scene. Most surprisingly, the most stirring of such interludes is actually the most widely-misunderstood: Dylan's alternately ballyhooed and beleaguered appearance with a band at Newport in 1965.

The grand finale gives way to a deceptively dramatic closing shot. Bob Dylan rides his motorcycle with a vengeance from the festival site in Rhode Island, the drama of his departure rising incrementally with the increasing speed on the bike. Yet the intrinsic theatrics of the scene nonetheless remain understated, even as the incident occurs after one final visit to Guthrie. While the camera lingers on the stony wind-blown features, it seems to capture the very moment Robert Zimmerman became the defiantly iconoclastic artist he has long been known to be.

Credits rolling shortly thereafter can read like a litany of the names of characters populating not just A Complete Unknown, but Bob Dylan's life as we know it from books and other cinematic enterprises. Most appear without fanfare or the literal introduction by which Norbert Leo Butz's self-righteous folk archivist Alan Lomax benefits, but certain figures are certainly worth noting; the most knowing of viewers will derive more than a little pleasure in spotting notable figures in this narrative who are prominent far out of proportion to their visible minutes.

Unobtrusive but integral to the storyline are Columbia Records producers John Hammond, who signed Dylan to the label, and Tom Wilson, who shepherded the precocious recording artist through his earliest forays with electric music. Likewise, musician Al Kooper (Blues Project, Blood, Sweat & Tears) assumes his unobtrusive role as the author of the famous organ part on "Like A Rolling Stone:" its significance from the nod of approval he is afforded by the central figure in the segment depicting the recording of the song from which this picture took its title.

During those implicitly profound moments and in intervals showing Dylan walking and riding his motorcycle around New York City, Phedon Papamichael's fluid camera work can be disorienting. Nevertheless, the cinematographer, along with editors Andrew Buckland and Scott Morris, use the ostensibly impromptu method to conjure a real sense of how Dylan's inner compass was evolving at the time his career was taking on a life of its own.

The most avid Dylanophiles may inevitably compare this motion picture experience to processing Martin Scorcese's documentaries No Direction Home (PBS American Masters, 2005), Don't Look Back (Leacock-Pennebaker, Inc., 1967), Murray Lerner's account of three successive years of Newport Folk Festivals The Other Side of the Mirror (Legacy Recordings, 2007) Todd Haynes' strikingly unconventional chronicle I'm Not There (Endgame Entertainment, 2007). In fact, the compulsion to compare the differing cinematic perspectives may also arise in the novice fan who, riveted from seeing this late 2024 premiere, becomes inspired to delve further into the depths of the lore that has arisen around the movie's still-thriving subject.

However, for the differing demographics as well as the casual theater attendee—all of whom may have contributed to the applause erupting at the picture's conclusion in a Vermont theater—it might be well to ponder whether or not a tagline in TV advertising for the title carries a decidedly wry undercurrent: "inspired by the true story of Bob Dylan."

Tags

Film Review

Bob Dylan

Doug Collette

Searchlight Pictures

Pete Seeger

Johnny Cash

Woody Guthrie

Joan Baez

Alan Lomax

John Hammond

Al Kooper

Blues Project

Blood Sweat and Tears

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.