Home » Jazz Articles » Live Review » The Necks: Philadelphia, PA, September 22, 2012

The Necks: Philadelphia, PA, September 22, 2012

Performing to Food Court

Live Arts Festival + Philly Fringe

Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts

Philadelphia, PA

September 22, 2012

The prospect of Australian trio The Necks providing a live soundtrack for a theatrical production would seem to be either a perfect idea or an absolutely flummoxing mistake. The longstanding group is known for long, slowly-developing improvisations, owing a bit to trumpeter Miles Davis, a bit of something else to minimalist composer Steve Reich, but for the most part being something very much its own. Thegroup might have a dramatic peak in an hour of playing—it might even have two or three—but it would rarely follow the three-scenes-with-an- intermission itinerary that theater usually calls for.

Fortunately the (also Australian) Back to Back Theatre Company isn't usual theater, as evidenced by their joint production Food Court, which was staged at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts as a part of Philadelphia's Live Arts Festival + Philly Fringe. On September 22 (the third of a three-night run), The Necks forged a perfect hour of tandem abstraction, tension and release.

For 25 years, Back to Back has crafted unique theatrical productions through the brainstorming and group improvisations of the company's members, all of whom have mental disabilities. Food Court, the company's most recent work, was not about soliciting sympathy or demanding equity. It was about confronting cruelty, deep cruelty.

The show began with the band—pianist Chris Abrahams, drummer Tony Buck and bassist Lloyd Swanton—appearing submerged in the pit, Swanton's bass head the only thing breaking the line of the stage. They played close to 10 minutes before the first actor took the stage. Of course, every Necks performance is different, but the trio seemed to move through ideas and motifs a little more quickly, like a proper overture, which is to say that the motion in its minimalist improvisation was noticeable.

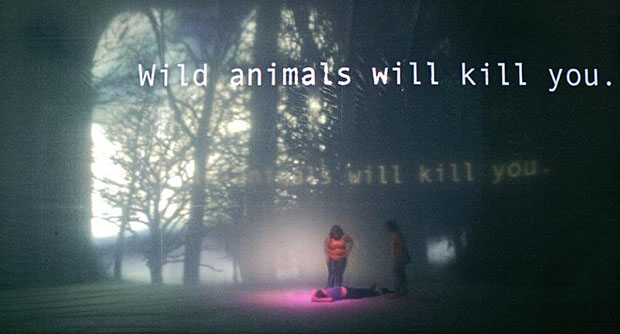

There was no clear storyline to the performance piece, essentially two women involved in horrendous cruelty against a third and two men who were primarily functional—arranging chairs and holding microphones for the women within the bare stage "food court," where these women met. A food court of course is that nebulous zone in shopping centers that does not belong to any one business, but is available for people eating at any of the surrounding fast food restaurants. But in this case it was also, perhaps, the court of public opinion that views them (both the actors and the characters) as not just different but undesirable—unsightly and untouchable. "Fat" was one of the insults most commonly hurled in the verbal derisions, delivered in both thick Australian accents and supertitles.

Nor was there release, context or moral, and yet it carried the weight of a tragic opera. What made the onslaught of two-against-one debasing work as theater (in fact, what made it even tolerable) was the beauty in which it was set. The staging made for a perfect physical realization of The Necks' music: aimless, tense and with a veneer of beauty. Much of the action took place behind a scrim and with delicate backlighting—inspired, according to director Bruce Gladwin, by artist James Turrell and giving it a milky soft focus. The derisions grew to harassment, the verbal attacks became physical and the production culminated with a soliloquy borrowed from the monstrous Caliban in Shakespeare's The Tempest.

In a talk with the cast after the show, Gladwin said that while improvising scenes, the cast had come up with the idea of trying to push back against actors with disabilities being "perceived in some kind of holy manner." The project was developed over four years of work-shopping, during which Gladwin played Necks records to establish timing and a mood for improvisation. It was only when they were nearing production, he said, that they asked the band to join them in performance. Abrams, Buck and Swinton watched one rehearsal and joined them for a second before they took it to the stage.

While disability dictated the tone of the play, the scene could just as easily have been a prison or a schoolyard. It could have been most anywhere, really, slowed to the point that human frailties, insecurities, resentment and anger could be discerned and dissected, and with musical accompaniment that demands attention.

Photo Credit

Jeff Busby

Tags

The Necks

Live Reviews

Kurt Gottschalk

United States

Pennsylvania

Philadelphia

Miles Davis

Steve Reich

Chris Abrahams

Lloyd Swanton

About The Necks

Instrument: Band / ensemble / orchestra

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.