Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Nothing's Bad Luck: The Lives of Warren Zevon

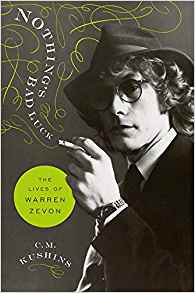

Nothing's Bad Luck: The Lives of Warren Zevon

Nothing's Bad Luck: The Lives of Warren Zevon

Nothing's Bad Luck: The Lives of Warren Zevon C.M.Kushins

416 pages

ISBN: #978-0306921483

DaCapo Jazz Trio

2019

Even just a cursory glance through C. M. Kushins' biography of Warren Zevon reveals it as a textbook example of what a thorough contemporaneous biography should be. The fastidious approach the author takes to his subject includes not just the scholarly research of well-documented interviews and a complete discography, but acknowledgments eloquent in their heartfelt gratitude. Combine that expression with the often cinematic account of events and it's hard to believe this is the writer's first book.

Kushins sounds articulate and authoritative in recounting The Lives of Warren Zevon precisely because he knows his subject inside out. He speaks from the experience of interviewing family, friends and acquaintances who, each in their own way, provide a different perspective on the late songwriter and musicians (notably missing from which list but often quoted nonetheless, is long-time mentor and collaborator Jackson Browne). The multiple and clarified perspectives arising from Kushins' scrupulous work are an absolute necessity in capturing the mercurial nature of a man who could become as absorbed in fishing as writing a symphony, while rock and rolling in between. It should come as no surprise Nothing's Bad Luck is also as entertaining a read as it is.

In that light, the initial chapter titled "1903-1966" is something of a red herring. It will decoy a reader into expecting a lengthy treatise on Warren Zevon's ancestry when, in fact, Kushins offers a fairly pithy encapsulation of the man's Russian/Jewish lineage, plus a clear delineation of a family history in which the author is (too?) quick to point out how the various diverse personalities found their way into that volatile makeup of his subject's. And while many of the incidents described are, not surprisingly, familiar to readers of previous works devoted to Zevon's life, it is only in The Lives of Warren Zevon it becomes clear that, had he not succumbed to his addictions and substance abuse so early in a life that ended so prematurely due to illness, this brilliant, eccentric individual might well have fully evolved into a true renaissance man.

Passions extending beyond music—a sufficiently varied one on its own terms—including all manner of literature and sports, form the basis for a complex persona extended and amplified by the Warren Zevon''s own self-consciousness. Drinking at an early age, for instance, continued as fodder for his creativity, or so he would have himself think, and his fondness for various drugs only exacerbated a violent temper that may very well have been in his DNA. C.M. Kushins' erudite exposition of the man's career arc moves at an engaging and fleet pace, the tempo interrupted at times early on, by some odd choices in vocabulary: is a reader 'vivacious' or 'voracious'? And do objects 'exhume' or 'exude' an odor?

Errant spellcheck doesn't excuse sloppy editing and it's a credit to the author's storytelling skills and the depth of his research—plus a suspense intrinsic to the tale he's telling, even if you know the outcome—that such questionable instances remain mere flecks of imperfection. Otherwise, Kushins lays out a fairly fluid narrative in which passages describing recording activities (right down to the specific choices of musicians) alternate with those of Warren Zevon's personal life. It's a seamless quality reflective of the man's pursuits.

And within and around the chronology, the author engages in some analysis and interpretation of the compositions indicative of his passion for his subject. The flow of those intervals enhances the film-like progression of Nothing's Bad Luck: they are akin to spoken word segments or first-person interview snippets with the actors, in-character and out. Somewhat less successful are those sections where Kushins engages in some psychoanalysis within which he becomes entangled in contradictions: for instance, does isolation nurture Zevon's creativity or his predilection to indulge in drink, drugs and promiscuous sex?

It's clearly both, at different times, under a variety of circumstances, such as the writing in prep for the Excitable Boy (Asylum, 1978) album. The writer is certainly aware of that, he just needs to better clarify his awareness of the paradox(es). He is otherwise utterly clear on that which caused Warren Zevon to alternately charm and repel friends intimate and otherwise, as well as family members; that particular roller-coaster, in fact, turns out to be a constant in the man's life and, as mentioned before, may be the rationale behind long-time mentor and collaborator Browne's name not included in the tally of interviewees (in contrast, Julie Bowen's is there, without any other between the hardcovers); based on some exposition of their relationship, around the death of the latter's own spouse and a calamitous tour of Europe with Zevon, he may have, in fact, become too close to be objective.

That's not the case with C.M. Kushins, however, and he should be applauded accordingly. That said, his depiction of The Lives of Warren Zevon may, to some readers, sound like a cold-blooded portrayal of a cold-blooded human being. To be sure, even though the author's intellectual inspection of his subject comes through almost on a visceral level at times, this book otherwise contains only scant emotional warmth, certainly in comparison to that written by his spouse Crystal, I'll Sleep When I'm Dead: The Dirty Life and Times of Warren Zevon (Ecco, 2008)). As a result, Warren Zevon is a decidedly unsympathetic figure through the first third or so here. Still. the reality is Kushins performs an important function by positioning his work at a virtual mid-way point between the aforementioned bio and the ever-so-cerebral (to a fault?) James Campion's Accidentally Like a Martyr: The Tortured Art of Warren Zevon (Backbeat, 2018).

One of the most admirable accomplishments with this book—and there are more than a few—is Kushins' seamless interweaving of recording information and his own analysis of the results. There are times, however, such as the interlude devoted to Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School (Asylum, 1980) when his writing sounds forced, almost bordering on over-explaining: one summary is plenty sufficient devoted to the varied styles included on that record. His delineations of the individual songs and the overall composition of the record are otherwise clear and distinct enough, more in keeping with his prose virtually everywhere else: the fluid unreeling of prose seems to generate, then ride, a momentum all its own.

Nonetheless, at about the midway point of this book, a certain monotony sets in. Not surprisingly, this is the interval where, having stopped drinking (at least to great excess as in the past), Warren Zevon's addictive personality has taken him to harder drugs, specifically, cocaine and painkillers. At around this time too, his fortunes as a recording artist have fallen off from the peaks he had attained both critical and commercial, so he stands on the verge of being dismissed from the roster of an Asylum label in the midst of drastic changes from its original David Geffen-conceived, artist-friendly approach. It only stands to reason, then, that Kushins' narrative would drag here, yet, in a very real sense, this tone, intentional or not, accurately mirrors Zevon's life at this particular juncture.

That somewhat turgid tempo continues more or less til the man becomes wholly and completely sober in 1986. At this point, the story Kushins tells turns noticeably brighter, borderline colorful, as Warren Zevon's moves fully into sobriety, albeit somewhat fitfully. Not surprisingly, he follows his muse (or his muse follows him) to begin writing memorable material again and performing in a way that invites deserved attention, rather than deflecting the wrong kind, as in the years just prior. All of which occurs with the unflagging assistance of a record label manager, Andrew Slater, who turns his fan stance toward the practical means and ends of recording and promotion on behalf of an initially recalcitrant object of devotion.

The initial promise of a new recording contract isn't exactly for naught, at least as C.M. Kushins describes it. Sentimental Hygiene (Virgin, 1987) and Transverse City (Virgin, 1987) reintroduce Warren to an even larger audience than that which stayed loyal to him at his low(est) points. But as the author recounts Zevon's two-album tenure with that nascent label and moves on to the circumstances that gave birth to Mr. Bad Example (Giant, 1991), Mutineer (Giant, 1995), then Life'll Kill Ya (Artemis, 2000) and My Ride's Here (Artemis, 2002), he reveals a deeply-entrenched work ethic and meticulous studio craftsmanship, not to mention openness to new technology, that found their level in the newly-sober and stable Warren Zevon. Such well-established good habits offset at least to some degree the ever-increasing quirks of the man's personality, including a growing OCD.

In an ironic twist the subject of this book would relish, the narrative takes on a more informal, almost conversational tone. The man who wrote "Werewolves of London" works assiduously to dispel that novelty aspect of his oeuvre as wends his way through the tragicomic series of major label recording deals; the upshot of that tortuous process ultimately leaves Warren Zevon, like so many professional musicians, touring to make a living. It's a fate that the man views with equanimity, at least based on the author's quotes culled from media interviews over those years in the Nineties during which Zevon perfected his own recording techniques. Those otherwise mundane elements of the story heighten a dramatic conclusion that might be deemed implausible were it submitted as a story idea for a Hollywood movie script.

In fact, VH1 (Inside) Out -Keep Me in Your Heart (Artemis, 2004) documented on film the last months of Warren Zevon's life as he battled cancer, strove to record his final album and eventually hung on, with no little travail at certain points, to complete The Wind (Artemis, 2003). The multiple posthumous Grammy Awards bestowed upon the work were decidedly ironic, but no less the poetic justice by which Zevon was able to survive long enough to see daughter Ariel give birth to twins before he passes; the turbulent relationship he and she endured over the years, similar to that the father conducted with son Jordan, mirrors the fractious on-and-off intimacy of Warren Zevon's other intimate relationships, friends and significant others alike.

And even though C.M. Kushins never got to meet and converse with the object of his admiration, he might count himself among that number. At least based on his "Coda" to Nothing's Bad Luck (the phrase one of Zevon's favorite aphorisms, perfectly suited to the arch air in the posed cover photo). Befitting its subtitle (and its seven-year gestation period), The Lives of Warren Zevon is nothing if not exhaustive, fully and completely so with its author adding that aforementioned footnote to it all: what at first sounds like self-indulgent self-congratulations quickly turns into what sounds like nothing so much as an honest and forthright acknowledgment of the object of his admiration as a self-renewing source of inspiration.

With that inclusion, this author reminds readers what lies at the heart of every fan's long-term and deep esteem for their favorite practitioners of any of the arts. Kushins certainly aimed high in his ambition(s) for this book and he exceeded his goal(s), to the betterment of anyone who reads it.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.