Home » Jazz Musicians » Johnny "Hammond" Smith

Johnny "Hammond" Smith

Johnny "Hammond" Smith was part of the golden age of jazz organ that flourished for about 15 years, beginning in the mid-1950s. His own record label alone, Prestige, boasted such top organists as Shirley Scott, Brother Jack McDuff, Don Patterson, and Charles Earland. And looming over the entire crowded field of B-3 pilots was Jimmy Smith (no relation). Born John Robert Smith in Louisville, Kentucky, December 16, 1933, he has a mildly musical background: “My mother sang in the choir, my sister and others in the family were musical, but I’m the only one who became a professional.” “My influences were Charlie Parker, Dizzy, Bud Powell, Art Tatum, all the people who were really happening in the mid-1940s. I guess you could say I made my professional debut at 15. I had a buddy who also played piano, and we’d both slip into a little club down the street and take turns playing for whatever they’d put in the kitty.” Smith was 18 when he left Louisville. For a while, he lived in Cleveland, playing with groups led by saxophonist Jimmy Hinsley and guitarist Willie Lewis.Around the time he came of age, his ears were captivated by the sound of Wild Bill Davis, who had just begun to show the possibilities of transferring modern jazz sounds to the electric organ. Inspired by Davis, and also to some extent by Bill Doggett, Johnny gradually made the changeover from piano to organ himself. “I was the first jazz organist in Cleveland, or to put it another way, the first jazz musician in Cleveland even to own an organ. I began working around in small combos.Believe it or not, I was playing from the very start pretty much the way I’m playing now. I played single lines then, then built up to shout out-choruses with big chords and so forth, just the way I do today. The only difference at first was that I hadn’t turned the vibrato off the organ, whereas Jimmy Smith had. Later, around 1957, I began turning it off.” Shortly after Hammond’s acquisition of an organ, Wild Bill Davis left the Chris Columbus group in which he had been working. Johnny got the job with Columbus and went almost immediately to New York. From that point on, he shuttled between New York and Cleveland as alternate homes. In 1958, he had his first opportunity to extend his popularity through records.

Read moreTags

Johnny "Hammond" Smith: Wild Horses Rock Steady

by Arnaldo DeSouteiro

Born John Robert Smith on December 16, 1933 (in Louisville, KY), formerly known as Johnny Hammond Smith, and later as Johnnny Hammond, one of the all-time best jazz organists passed away on June 4, 1997, in Chicago, Illinois. For some of his early fans, some of the best albums he recorded were done for Prestige in the Sixties. A younger generation, who grew up listening to the hip-hop influenced jazz sounds of the 1990s, prefers Johnny's over-produced sessions for Milestone ...

Continue ReadingCTI Acid Jazz Grooves by Various Artists

by Arnaldo DeSouteiro

The CD you are holding in your hands is a very special compilation. It's the celebration of CTI as one of the most “sampled" labels on Earth! For the past ten years, many CTI tracks have been cut up, sampled, scratched and looped to create new songs for a new audience. Many of the selections on this album (all of them produced by Creed Taylor and engineered by Rudy Van Gelder) represented the basic inspiration and major influence in the ...

Continue ReadingJohnny "Hammond" Smith: Opus de Funk

by David Rickert

Johnny “Hammond" Smith will always be tagged as the other Smith on the B-3, grouped together with a host of other organists who never managed to break free from the club circuit into the realm of true infamy. However, Smith's recordings are slowly making their way back into print via generous two-fer CDs from Prestige, giving us an opportunity to reassess the career of an artist stuck in the minor leagues.

At the time that the two sessions ...

Continue ReadingJohnny "Hammond" Smith: Good 'Nuff

by David Rickert

Good Nuff is a perfect title for a Johnny Smith record, given that it aptly describes most of his records. Johnny “Hammond” Smith never earned the acclaim of the other organist who bears his last name, and for good reason; he simply isn’t as talented or inventive as the one who carved out several dynamic sessions for Blue Note. Often resorting to a template of well-worn grooves and clichés, Smith is fortunate enough on the first of the two sessions ...

Continue ReadingJohnny Hammond: Breakout

by Jim Santella

The CTI jazz catalog holds many surprises. This one features a strong 8-piece band led by organist Johnny Hammond (1933-1997), who was known earlier as Johnny “Hammond" Smith. Recorded in 1971, the album emphasized swinging mood music with a flair for popular sounds. It marked a turning point in the career of Grover Washington, Jr. He, Hank Crawford and Eric Gale are all over the place, alongside Hammond's B-3. It’s a party. A previously unissued track, recorded shortly after the ...

Continue ReadingJohnny Hammond: Breakout

by David Rickert

A prime example of the CTI label’s indulgence in the commercial possibilities of jazz, Breakout gave Johnny Hammond the opportunity to escape from the long shadow cast by Jimmy Smith. Sticking with the Hammond B-3, by this time a bit old-fashioned as many had become enchanted with the Fender Rhodes, Hammond and his band contribute an album’s worth of soul jazz workouts. By this time, rock tunes had become the new would-be standards and Hammond proves that such unlikely candidates ...

Continue ReadingJohnny "Hammond" Smith: Open House

by David Rickert

The best organ jazz records fuse elements of gospel, blues, and soul together with the atmosphere of a jam session, as if a bunch of friends got together one night to toss a few back and play some tunes. Johnny “Hammond" Smith certainly has the right idea on the first of the sessions on this two-fer reissue; the instrumentation approximates that of Jimmy Smith's classic “The Sermon" but the music burns at a slightly lower temperature. Whereas Jimmy Smith punctuates ...

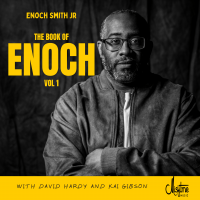

Continue ReadingPianist Enoch Smith Jr. Returns To Recording After An 8-year Absence With "The Book Of Enoch Vol. 1," Set For Nov. 7 Release On Misfitme Music

Source:

Terri Hinte Publicity

Enoch Smith Jr. gives the gospel music repertoire a fresh infusion of blues and swing with the heartfelt, hard-driving The Book of Enoch Vol. 1, to be released November 7 on his own Misfitme Music. Played by his trio of bassist Kai Gibson and drummer David Hardy, thealbum—Smith’s sixth, and his first in eight years—obviously draws deeply on the gospel tradition but presents its seven tunes in the context of soulful, infectious straight-ahead jazz. In other words, it might not ...

read more

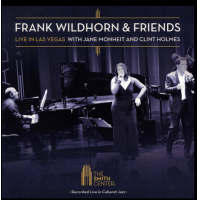

Frank Wildhorn Unveils 'Frank Wildhorn & Friends: Live In Las Vegas With Jane Monheit And Clint Holmes' A Dynamic Return To His Jazz Roots Recorded Live At The Smith Center Inside Cabaret Jazz

Source:

Jill Siegel

Frank & Friends: Live in Las Vegas with Jane Monheit and Clint Holmes, a captivating live album recorded at the Smith Center inside Cabaret Jazz is now available on all streaming platforms featuring 17 tracks lovingly selected by the renowned multi-Grammy, Tony, and Emmy Award-nominated composer and producer Frank Wildhorn for Jane Monheit and Clint Holmes. This album, produced by Frank Wildhorn and Myron Martin, features songs from Wildhorn musicals “Jekyll & Hyde”, “The Scarlet Pimpernel”, “ Wonderland,”” Camille Claudel” ...

read more

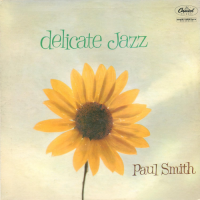

Perfection: Paul Smith - Under My Skin (1957)

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

Last weekend, I posted a video clip that included pianist Paul Smith accompanying Frank Sinatra. Smith belonged to a small group of superb West Coast jazz studio pianists that included Lou Levy, Jimmy Rowles and Pete Jolly. In the late 1950s, Smith recorded four albums for Capitol that became known as the Liquid Sound sessions. One of them was Delicate Jazz, recorded in November 1957. For this week's Perfection clip, I've chosen I've Got You Under My Skin. I'm not ...

read more

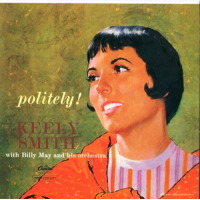

Perfection: Keely Smith - The Song Is You (1958)

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

Few pop singers in the 1950s could swing like Keely Smith. Anita O'Day was certainly one of them, but Smith was the finer vocalist and surely knew more songs and required fewer takes in the studio. In some respects, Smith was the female Frank Sinatra, able to move ahead of the beat, behind it and go a different way on song lines and pull them off. So many of her albums are excellent with a different feeling on each one. ...

read more

Eliot King Smith Teams Up With Audrey Martells (Chic) To Bring To Life The Story Of Josephine Baker

Source:

Glass Onyon PR - Keith James

In the 1920s, faced with the grinding poverty and segregation of East St. Louis, Josephine Baker took her dancing and musical talents first to New York, and then, at 19, arrived in Paris to perform with the Folies Bergère. Entranced by her reception and treatment by French society, she rose to stardom almost immediately at the Folies. She starred in multiple films, and scored a big hit song that summed up her reverence for the freedom she experienced as a ...

read more

Johnny Richards and Stan Kenton

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

Johnny Richards arranged several crackerjack albums for Stan Kenton. They include Cuban Fire!, tracks on Back to Balboa, Kenton's West Side Story and Adventures in Time. Even more exceptional are Richards's albums recorded as a leader, including Something Else, Wide Range, Walk Softly/Run Wild and Aqui Se Habla Español. With Kenton, Richards came a long way from his early neo-classical orchestrations in the late 1940s and early 1950s to the singular mid-decade sound that came to be identified with him. ...

read more

Backgrounder: Johnny Hammond - Breakout

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

As Johnny “Hammond" Smith became increasingly popular, he added his middle nickname to avoid being confused with guitarist Johnny Smith and organ great Jimmy Smith. He began recording as leader in 1959 and was a sideman throughout the 1960s. In 1971, Creed Taylor signed him to Kudu Records, his soul-flavored subsidiary of CTI. Smith's album Breakout (1971) was the first album released on the new label. The LP is notable for its terrific mix of tracks and the stellar musicians ...

read more

Johnny "H" Smith: Open House

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

Organist Johnny “Hammond" Smith was relentlessly tasty. Whenever I dig into one of his albums, my feet can't stop moving. Hi grooves and chord voicings were intoxicating. One of his finest albums from the first track to the last was Open House. Recorded for Riverside in 1963, the album featured Thad Jones (cnt,tp); Seldon Powell (ts,fl); Johnny “Hammond" Smith (org); Eddie McFadden (g); Bob Cranshaw (b); Leo Stevens (d) and Ray Barretto (cga). Smith also was a wonderful composer. He ...

read more

Mrs. Johnny "Hammond" Smith

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

It's unclear who gave Johnny “Hammond" Smith his middle name. In all likelihood, it was Smith himself, to distinguish himself from Johnny Smith, the well-known jazz guitarist. “Hammond" Smith was born in Louisville, Ky., in 1933 and began recording on the organ in the late 1950s just after working as singer Nancy Wilson's early club accompanist. After recording steadily for Prestige as a sideman and leader during the 1960s, Smith signed with Creed Taylor's Kudu Records in the early 1970s. ...

read more

Johnny "H" Smith: Opus de Funk

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

Organist Johnny “Hammond" Smith isn't as well known todayas organists like Jimmy Smith, Jack McDuff, Shirley Scott, Don Patterson and Charles Earland. I'm not sure why. Perhaps his name was too close to Johnny Smith's (the guitarist) and John Hammond's (the producer). Nevertheless, Smith was a high-energy player with enormous soul power and restraint. His recording career roughly divides into two parts—his jazz-soul sessions for Riverside and Prestige in the '60s and his jazz-funk CTI records of the '70s for ...

read more