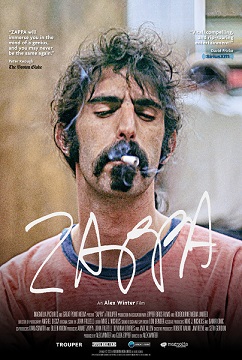

Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Zappa

Zappa

Alex Winter

Alex Winter Zappa

Magnolia Pictures

2020

Composer, guitarist and iconoclast nonpareil, Frank Zappa was never an easy artist to pin down, as Alex Winter's perceptive and entertaining documentary makes abundantly clear. If an artist's music should speak for itself, what are we to make of Zappa's freakish '60s collage of doo-wop, Stravinsky, rock and burlesque humor, his jazz-rock leanings in the first half of the 1970s, the coarse satire, his musique concrète and contemporary orchestral works? For one thing, Zappa never stood still; there is no suggestion in the documentary's two hours of the man ever taking a family holiday in twenty-five years, or even having time for friendships. Instead, this famously workaholic composer's life appears to have been a never-ending composition. For another, Zappa's obsession with music meant that writing a 'pop' tune or composing for the Kronos Quartet posed equally serious musical questions.

With unprecedented access to Zappa's archives—a veritable library of aisles of shelving housing tapes, reels, home videos, artwork and documents—Winter peels back the layers of a fascinatingly complex man: emotionally guarded yet outspoken; a Pied Piper-esque figurehead of the '60s counter-culture and yet overtly anti-drugs; a family-loving man who openly indulged his eager groupies; highly articulate yet an exponent of frequently puerile humor; a self-taught musician/composer whose music was often fiendishly difficult to perform; a self-described entertainer who collaborated with classical giants Zubin Mehta, Pierre Boulez and Kent Nagano. Zappa was, as one observer puts it, "a walking mass of contradictions."

Strikingly, in terms of minutes, there is relatively little music in Winter's film; there are plenty of snippets throughout, and certainly enough to underline the extraordinary breadth of Zappa's output, but the music, as Winter rightly adjudges, is only half of the story. Scenes of adoring Czechoslovakians at the dawn of the post-Soviet era welcoming Zappa's arrival at the airport as if "the King of freedom showed up," or of a sartorially conservative Zappa testifying before the United States Senate in his battle against musical censorship, are reminders of the political and cultural roles he undertook, or seemed to represent.

Whereas the God-fearing, conservative right-wing in America viewed Zappa as a moral threat, those people under the Communist boot in Eastern Europe championed him as the maximum representative of freedom of expression. Winter holds a mirror to both the outrage and the reverence that Zappa provoked in roughly equal measure throughout his career, and it is this duality that makes for such a fascinating tale.

Testimony comes from many of those who worked with Zappa, including Ian Underwood, Mike Keneally, Steve Vai, Ray White, Ruth Underwood, Bunk Gardner, and David Harrington of the Kronos Quartet. Johnny "Guitar" Watson's validation testifies to Zappa's R&B roots, when as a teenager in San Diego Zappa played drums in a racially integrated band, drawing on the music of Clarence Gatemouth Brown, Elmore James, Lowell Fulson and Watson. Gail Zappa, Franks' wife of twenty-five years, features prominently, as do archival interviews with the man himself, who fittingly, provides a hefty slice of the film's vocal narrative.

Bunk Gardner, woodwind player in the original incarnation of the Mothers of Invention from 1966 to 1969, recalls how the dissolution of the iconic band—driven by Zappa's desire for greater financial control—came "totally out of the blue." Decades on, Gardner still seems bewildered by the abrupt ending. Footage from the Garrick Theatre, New York, where the Mothers of Invention played a six-month, five-days-a-week residency in 1967, provides a glimpse into the colorful anarchy of Zappa's first great vehicle. "The whole world was absolutely absurd" Zappa reminisces of those turbulent days, "so here it is—we're giving it back to you."

Bruce Bickford, who provided the brilliant stop motion clay animation for several of Zappa's videos between 1974 and 1980 gets to the crux of Zappa's modus operandi: "All he could think about was control—his control."

The same desire for control that led Zappa to disband the Mothers of Invention in 1969 after a tour that left him $10,000 in debt, would also lead Zappa to acrimoniously split from the Warner label, subsequently setting up Zappa Records, and later, Barking Pumpkin Records. In going it alone Zappa was something of a pioneer, and a highly successful one at that. Gail Zappa recounts how the Barking Pumpkin mail order company, established in 1982, recorded a healthy $1 million worth of sales that year. Arf!

Making music, not money, was Zappa's driving force, though he comes across in Winter's documentary as an astute businessman who never let sentiment cloud his decisions. Towards the end of his career Zappa used his arena-filling rock projects more as a means to finance his orchestral, classical ambitions. In a sense, it was what Zappa had always aspired to, since he discovered the music of Edgar Varèse as a fifteen-year-old. "I started writing orchestral music before I ever wrote a rock 'n' roll song," Zappa states.

Zappa's collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1983 produced two albums, though Zappa, ever the perfectionist, was not entirely happy with the results. "Frank was a slave to his inner ear," says guitarist Steve Vai, explaining how other musicians' limitations were a cause of great frustration for Zappa. More and more, Zappa chose to compose on the Synclavier, which had two advantages: firstly, it could do things that musicians couldn't; secondly, it was cheaper, Zappa rationalized, than hiring an orchestra. Composition was one thing, performance was another.

Throughout the film there is an underlying sense that Zappa was a frustrated classical composer—frustrated more by conventions than anything else. It wasn't until the very end of his life, when approached by the German chamber orchestra Ensemble Modern, that Zappa found classically trained musicians who wanted to interpret his music.

In a brief clip from 1992 of Zappa conducting the Ensemble Modern before a packed hall in Frankfurt, on music that would become The Yellow Shark (Barking Pumpkin, 1993), he seems almost happy. The success of the performance and the adulation of the audience is particularly poignant knowing that it was to be Zappa's last public performance. On December 4, 1993, just shy of his fifty-third birthday, Zappa succumbed to the terminal prostate cancer that he had being living with for some years.

Long-term Zappa fans will no doubt be familiar with the biographical detail in Winter's film, and in truth there are no truly great revelations. Still, the previously unseen footage, and the insightful contemporary accounts of his peers combine to shed at least some new light on the Zappa story.

Perhaps the appraisal of the Kronos Quartet's David Harrington comes closest to capturing Zappa's musical spirit, and his outlier status in America: "When I think of Zappa's life's work I'm reminded of Charles Ives, Harry Partch, Sun Ra. These are American experimentalists that totally reimagined the way music might be heard, might be composed, and Zappa belongs in that tradition."

Artfully shot and edited, Zappa is a nuanced, balanced portrait of a creative maverick that not only invites reappraisal of Zappa's modern classical music, but of his enduring cultural significance too, both within and beyond America's borders.

Tags

Film Review

Frank Zappa

Ian Patterson

Magnolia Pictures

Johnny Guitar Watson

Clarence 'Gatemouth' Brown

Elmore James

Lowell Fulson

Sun Ra

Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention

Dweezil Zappa

Bunk Gardner

Ruth Underwood

Ian Underwood

Kronos Quartet

Alex Winter

Steve Vai

Mike Keneally

Ray White

David Harrington

Bruce Bickford

Ensemble Modern

The Yellow Shark

Barking Pumpkin

Charles Ives

Harry Partch

Zappa

Zappa the movie

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.