Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Ugly Beauty: The Music and Mind of Ben Allison

Ugly Beauty: The Music and Mind of Ben Allison

I like the idea of writing and preparing music that is intellectually stimulating that also appeals on an emotional level-there's something immediately accessible about it—a groove people can relate to, or a funky tambour that catches your attention, but it also has some deeper layers that you discover over time.

All of us have a story in our head-a myth of how a new jazz talent gets discovered. Here's how it goes:

All of us have a story in our head-a myth of how a new jazz talent gets discovered. Here's how it goes: The young musician—let's call him "the Kid"-practices alone in his bedroom for hour upon hour, playing along with the records of his hero, who we'll refer to as "the Star." It doesn't really matter what instrument the Kid plays, but let's say it's the trumpet just to make the image.

When the Kid reaches a certain age, the Star dutifully comes to play a gig in town. The Kid, of course, goes to the show; it's good if he sneaks out of his house to see the show, but not necessary. In any case, for some reason—a bit of fate, or the hand of God reaching down to intervene-one the Star's men (of course, it's the trumpet player) can't make it to the show; he's sick, or his car breaks down, and the Kid gets to sit in with the Star. The Kid doesn't design it this way-somebody has to push him up on stage or declare for everyone to hear "hey, the Kid here can play trumpet!" The Kid doesn't want any of this to happen.

As it ends up, of course, the Kid knocks the Star out with his playing. At the end of the last set, the Star pats the Kid on the back and gives him some understated compliment, then tells the Kid to look him up in New York or Chicago or wherever it is the Star is from. The rest is history-so much so that it's probably not even included in the story, so certain is the Kid's future greatness.

It's a great story that's both compelling and seductive. More importantly, it jives with the public perception of jazz as a field of artistic endeavor populated by the eccentric but prodigiously talented loners—a picture that Ken Burns' recent sepia-toned jazz documentary has only reinforced.

But this idea of what jazz is, and what it takes to make it as a jazz musician is a dream-fantasy in its purest form. It certainly is not representative of what it takes to make it in the early 21st century as a jazz musician, and probably isn't even representative of what it took to make it in the golden years of jazz back in the 1920s, '30s, and '40s.

Finding success and recognition as a player these days is more about launching a new business—with your music as the product—than it is about "getting discovered." Aspiring jazz musicians need to not only develop their chops and negotiate "the scene" in whatever city they happen to be living in but also prove adept at marketing and promotion, entertainment law, and even graphic design. Unlike "the kid," who is pushed onto stage and must only prove his talent, today's jazz musicians need to take an active role in the creation of their own careers-networking with and pulling together the right musicians to record and often produce original compositions, hooking up with the right label to record and distribute your work, then helping to get your music out there by promoting yourself and your recording with interviews, tours, web pages, and more.

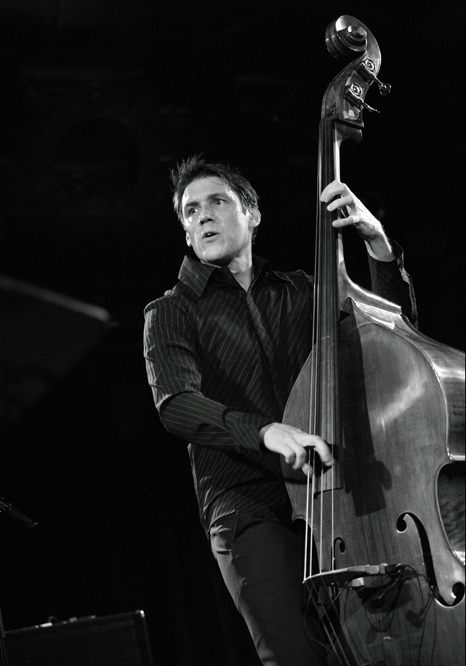

No jazz musician better exemplifies the entrepreneurial strain of successful, young jazz musicians than bassist/composer Ben Allison. Allison, a talented player, whose playing and compositions often weave seductive melodies into otherwise complex compositions, or combine toe-tapping grooves with far-out orchestration and hard-blowin' solos from Allison and his band mates.

Allison's four recordings as a leader on the Palmetto and Koch jazz labels have garnered both critical attention and solid airplay, especially on the airwaves of public and college stations. Allison's two releases with The Herbie Nichols project on the SoulNote label were similarly well received, with the group receiving Downbeat magazine's TDWR (Talent Deserving Wider Recognition) designation in 2000.

Even more impressive are Allison's accomplishments off the stage, where he and a group of friends founded the Jazz Composers' Collective in New York City, a loose non-profit organization that raises money to support and promote the work of talented young composers working outside of the commercial mainstream. And, as if that wasn't enough, Allison is also the owner and proprietor of his own Manhattan restaurant/nightclub, and a frequent lecturer, with countless seminars on topics ranging from "Music Publishing: What Every Composer Should Know about the Music Business," to "Band-leading and Composing for Small Groups," to "Non-profit Arts Organizations: a Musician's Guide to Self-Empowerment."

Ben and I sat down to talk about his latest album, 2001's Riding the Nuclear Tiger on Palmetto, but we also had the chance to talk about his struggles early on, and the do-it-yourself aesthetic to making it that he has helped pioneer and promote.

All About Jazz: How did a nice suburban boy like yourself end up playing jazz?

Ben Allison: I went to an art high school in New Haven (Connecticut) where I grew up called the Educational Center for the Arts. They had a really great program. The jazz ensemble instructor was a local pianist by the name of Bill Brown. I guess he's the person who first introduced me to jazz. At that time the Yale Radio Station, YBC, was playing jazz—I guess daily. So I tuned into that. It was just inevitable to end up in New York City... the Jazz Center of the Universe, I'd say.

AAJ: Them's fightin' words up here in Boston.

BA: I'm sure. But, you know, New York is a cultural Mecca. It's not just jazz. The thing about NYC is the sheer amount of great musicians of any genre. As an example, I got this record a few weeks ago by Mamadou Diabate, he's a Kora player from the Diabate family of musicians. So, you know, I'm thinking about this guy and I really loved his record, so I call up his label and it turns out he lives out in New York. We got together. We played. That's the type of thing—you know—that's why I'm there. There's so much going on.

AAJ: Did you start out playing bass?

BA:I started out playing guitar a little bit as a youth. I think my first professional work, if you want to call it that, was as a percussionist playing Conga drums and the like.

AAJ: Was it intimidating to go from New Haven to NYC? I've talked to other musicians about this—there is an intimidation factor with New York City because of all the great musicians who are there.

BA: Yeah, a little bit. Especially since I was kind of a late bloomer as far as a player was concerned. I didn't start playing acoustic bass until my senior year of high school. It takes a bit of time to get that together. So, it took me a minute and, believe it or not, in those days I was kind of a shy person—that's changed in a hurry—it was just a matter of finding musicians who were on my level or hopefully a little bit better that would put up with me long enough to play. It's a matter of networking, but once you get going with it and showing up to enough sessions you start getting called and that's how it works.

AAJ: Your albums Medicine Wheel and Third Eye have had a lot of critical success. Both the Boston Globe and the New York Times picked Third Eye as top jazz album of the year. Were you prepared for the success of those releases and what in them do you think people found so compelling?

BA: I think the trick is not to think too much about it. As I'm preparing to do my next thing, I don't want to be thinking too much about comparing it to things that I've done before. I just use (the success of those albums) as a tool to try to get gigs, which is really what it's all about.

AAJ: What sets your music apart from the mass of other jazz releases out there?

BA: I like the idea of writing and preparing music that is intellectually stimulating that also appeals on an emotional level—there's something immediately accessible about it—a groove people can relate to, or a funky tambour that catches your attention, but it also has some deeper layers that you discover over time. Hopefully. That's my intention with it. I hope that that's something that comes through.

Also, I'm a big fan of people who know how to write good melodies. I love folk music and I love the simplicity of somebody like Neil Young or John Lennon or Joni Mitchell or even Duke—people that wrote melodies that had some kind of basic beauty to them. But I also think it's important to write music that has a little bit of quirkiness to it. I use the term "ugly beauty"-you know who I took that from-I like the idea of a beautiful painting hanging crooked on a wall. There's this thing of beauty that's a little askew. You know, the women I'm attracted to always have a slightly different thing about them. So, I'm trying to write that into the music and maybe that's what appeals.

AAJ: Riding the Nuclear Tiger is the new release on Palmetto. Where does the music on this album come from? Did you write it? Who contributed the tunes? What is the change in sound from what people heard on your previous albums?

BA:I wrote all the tunes but one, which (saxophonist) Michael Blake wrote. It's an extension of the other two Medicine Wheel albums. Some of the concepts of the other albums are fleshed out here. Using Extended techniques—pulling the string off the side of the bass as a sound. Frank Kimbrough, who plays piano on the album, prepared the strings with Metro cards (which are NYC subway cards) to get a buzzing sound. Just taking advantage of all those sounds. I've always been a big admirer of music that stretches the boundaries in that way. But I've also noticed that a lot of times those sounds are used in avant-garde contexts or 20th century music contexts or music that's out that's based purely on the texture, and I like to use those sounds as part of something that's larger, in other words, combining those sounds with an accessible melody or something you can latch onto right away. That's part of Medicine Wheel and this album extends that.

AAJ: In both these albums, your compositions are melodic and beautiful, but also challenging-you guys are pushing the envelope as musicians and taking great solos. Do you think there's more of an appetite out there in the general public than there was 10 or 15 years ago?

BA: I would hope so. I'm not really sure. The time that I came up in, in the mid to late 1980s, there was a real strong neo-conservative movement. Not to name names, but we called that generation the re-boppers, that was our term in New York. You know what I'm talking about.

AAJ: I'm thinking of the Young Lions...

BA: Yeah, it was a little on the conservative side for our taste. And packaged in the way that a pop star would be packaged, complete with look and wardrobe...

AAJ: And a very nostalgic look, as well, trying to recall the Blue Note look from the '50s and '60s.

BA: Yeah. I remember going to clubs and people would be dressed like they would have been dressed in the 1940s, as if that had anything to do with music. To me, it just kind of seemed silly. You know, it was alright. It was cool as a vibe—you know you go to a club that had a vibe and you'd dress that way, but some of these guys had convinced themselves that they were the bebop generation. They were living it and trying to pretend that it was happening as new music. And it seemed kind of anachronistic and I never really got that. So some of the things we were involved in were a reaction to that. There was also the Knitting Factory scene. We were all involved in that too, to a greater or lesser extent, but I didn't necessarily feel particularly connected to that. I always admired the musicians from all camps, but didn't feel any particular kinship to any one side. So one of the things we thought about the (Jazz Composer's) Collective was trying to forge our own scene-it wasn't uptown, it wasn't downtown, it was our thing.

AAJ: You formed the JCC back in 1992 when you were 25. It's such a wonderful idea, but I'm wondering... if you polled jazz musicians, a lot of them are discontented with the record industry and the way they're treated by record labels. What motivated you to actually get out and do something about it—create this organization? Did you have a particularly bad experience with an industry rep?

BA: I had a couple of bad experiences and it was the culmination of a particularly horrendous summer, the summer of '92, and it was just dark. There was nothing happening for me and I just kind of felt frustrated. We sat around a lot in coffee shops and in basements grumbling about the scene, and I realized that we had a tremendous amount of energy to expend, because we were expending it in feeling dark and talking about it.

So rather than expend it in that way, I had a flash—actually I was reading a biography of Alban Berg, who is a composer I very much love and was checking out at the time. They started an organization in I think the early '20s in Vienna called the Society for private Musical Performances, something Arnold Shoenberg and Webern and Berg set up. He was talking about how frustrated he was at the way they used to program his music. They would have a concert that would start with some Bach, then go to Mozart, then Webern, then back to Mozart, so when they got to the Webern stuff, people would just flip out-it didn't fit, it was out of context. And they thought the key would be to create their own context. So they got some patrons—some people who were interested in what they were doing, and they set up, basically, a loft scene. They would have somebody open up their space and they'd invite people who were into or curious about their music come to the concert. It would be a program of just their stuff. They'd have the right musicians performing and rehearsing it. You know, there's nothing worse than atonal music played by people who don't understand that language. And they had a newsletter that they published, and the idea behind that was to bridge the gap between the composer and the audience. They weren't above talking about what they were doing, because it's conceptual music and understanding the concept behind it allows you to appreciate it more and when you start to appreciate more, maybe you'd start to hear some things of beauty in the music that you hadn't heard before. And I thought, "wow, what a great idea" It seemed to apply to how I was feeling at the time and I thought that we could do the same thing in jazz.

AAJ: Who, aside from yourself, was involved in creating the Jazz Composers Collective?

BA: The original group was me, John Schroeder, a saxophonist who has since moved out west, Frank Kimbrough, and shortly thereafter Ted Nash got involved, and in subsequent years, Ron Horton, who is our newest composer in residence, and then the other composer in residence is Michael Blake. He got involved in '96. We'd been playing a lot together, but we asked him to be involved in the Collective about that time. Those are the four composers in residence, and also the players who are on my record. I play bass, Michael Blake and Ted Nash play reeds, Ron Horton plays trumpet and flugelhorn, Frank Kimbrough plays piano, Tomas Ulrich plays cello and Jeff Ballard plays drums.

AAJ: How do you decide whom you're going to play with? Also, as far as the JCC goes, how do you decide what composers or artists you're going to lend your support to?

BA:Well we kind of find each other. These are all friends of mine. That's one thing about the JCC that I think has allowed us to continue and maintain. There's a large amount of trust between us, and I think there has to be to play the kind of music we play. We support each others work and are committed to it, and that's really important to developing an ongoing scene. So I try to write music specifically for people I asked to be involved—take advantage of their particular strengths, capitalize on what they do best. provide a forum for them to get to their thing.

AAJ: Based on your experiences with the Collective, what has your experience been like with (record label) Palmetto? You have three albums out with them. Do you feel like this is a label that has encouraged you to be creative and explore your musical impulses—?

BA: Yes. Very much so. One of the things that's great about a small, independent label is that they're not as controlling about the music that you produce. I have complete control over my projects. And, in fact, I make the record and deliver it to them. This last record, they got the finished product. I can write it, produce it, mix it, all the post-production. I do all the graphic design on my albums too, just because it's a hobby of mine, and it allows me to present a complete package, you know? I think they're related. One thing about major labels is that people think you make a lot of money off of them, but in actual fact they cost so much to produce—their overhead is extremely high. Marketing, and post-production, they have a staff that they have to justify the cost of. So, in order for them to recoup their costs and make a profit, they have to sell many many copies. And the truth is that the jazz market is extremely small, and even a top seller is small-and that exists for pop music, too. Michael Jackson may not make the company any money in the long run, because his albums cost $100 million to make. They make their money on the first Nirvana album which maybe they spent $20,000 on. That's how record companies make their money. An independent label, obviously, they have pressure to sell records and they want to, but the costs are lower so I don't think they feel quite the pinch, so they can afford to give the artists a lot of creative freedom. If you look on the CMJ charts on a weekly basis, there's always a Palmetto artist in the top five.

AAJ: You're somebody who has gone out and done a tremendous amount and has been very proactive in getting your music heard and getting other people's music heard, so what advice to you have to young musicians?

BA: Some kids don't want to hear it. Some kids are married to the idea that you hang out on the scene, and then Wynton hears you and you're a star. That does occasionally happen-I know of two people in the history of jazz that that's happened to. Meanwhile, for the rest of us, it's a long, hard-fought road. And it's also a challenge to maintain your integrity and develop something that's personal. Even some of the people who have been singled out as rising jazz stars have suffered at the hands of the media because they were under so much scrutiny. I think they actually would have evolved in a different way if they had been free to hone their craft and really develop an original sound over a period of time. It takes a long time, you know? When I was a student, Joe Lovano used to say "knock on doors, but don't knock any doors down... take your time, don't be in such a hurry, in the meantime, stay persistent and consistent. Hone your craft. When you're ready, the industry will come to you and when they do it'll be on your terms." I just like that whole philosophy of not freaking out about it and taking your time and in the meantime, work on it yourself. I get a lot of satisfaction, even if nothing's going on, of just working on it.

Tags

Interview

AAJ Staff

Chicago

New York City

Boston

Mamadou Diabate

Neil Young

John Lennon

Joni Mitchell

Michael Blake

Frank Kimbrough

Ted Nash

Ron Horton

Jeff Ballard

Tomas Ulrich

Ben Allison

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Ben Allison Concerts

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.