Home » Jazz Articles » Chats with Cats » The Jazz Photographer: Philip Arneill

The Jazz Photographer: Philip Arneill

The whole project has always been about being as unobtrusive as possible because you want to capture the place as best you can so you get a sense of what it’s like to be in there

—Philip Arneill

He's also explored other topics in his work such as jazz dancers, American life, and Irish religious edifices but his perspective as an outsider along with his photographic expertise make for a fascinating point of view.

About Philip Arneill

Philip Arneill is a Belfast-born writer, photographer and researcher. Co-creator of the Tokyo Jazz Joints audio-visual documentary project, his Tokyo Jazz Joints photographic monograph was published by Kehrer in July 2023 to widespread acclaim. Philip's writing and photographic practice explore the illusory ideas of home and culture by examining insider-outsider dynamics and autoethnographic issues of place and identity, combining images with creative nonfiction and fiction texts. His photos have been published and exhibited worldwide, and his projects have featured in a wide range of online and traditional print and broadcast media.All About Jazz: As a photographer what got you interested in jazz and jazz clubs?

Philip Arneill: Well, actually, the current project is not really jazz clubs but I'll come back to that because what got me interested was jazz clubs [laughs].

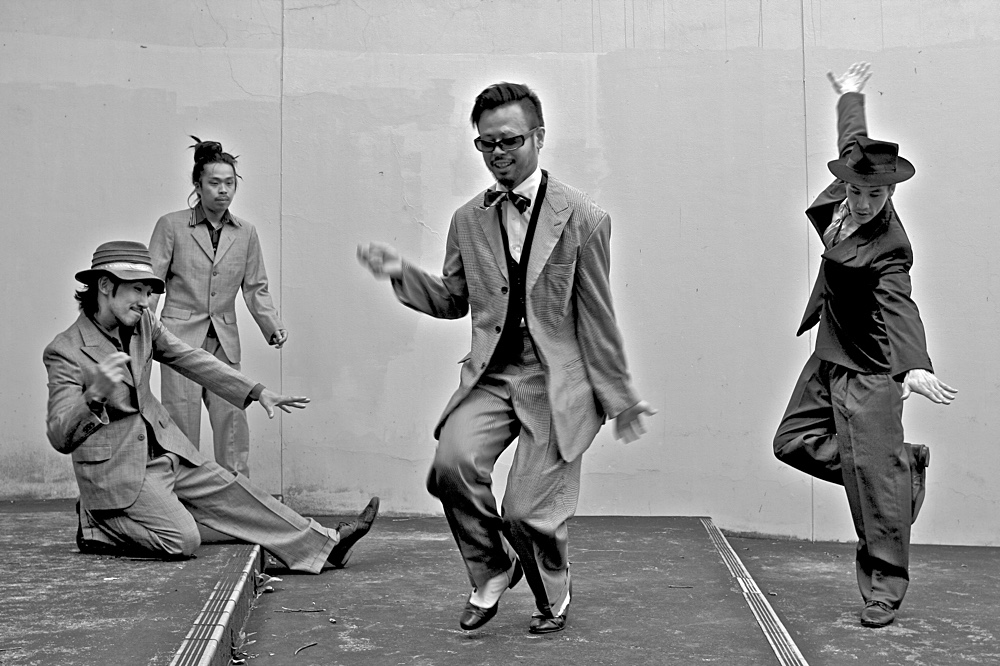

I moved to Japan in 1997 when I was 22 and I had listened to a bit of jazz. I was into hip hop at the time so that links with funk, soul, and jazz. That's what got me into it. After a few years in Tokyo I met a guy from London and he was running a jazz dance night, which I know resonates differently in America, but was based around these underground '80s clubs in the UK. These dancers were dancing to really heavy bebop and really heavy Latin music. It's quite antisocial music. It's not what you'd hear and think, "oh, I'm going to dance."

This kind of style was just known as UK jazz dance but, in Japan, it was starting to be called bebop dance. There was this event called Bebop Square and I started going along and started photographing it. That was the first music focused project I ever photographed. It largely involves crawling about on dance floors and getting kicked, that kind of thing. While the dancers would dance, these circles would form, it was very dark, and quite hard to photograph.

Through that, I got more into jazz music and then this idea of Tokyo Jazz Joints actually came quite a bit later. In 2014 I was in one of these places down in Kyoto and thought to myself, it would be interesting to photograph these places because they may not always be here.

So, I contacted James Catchpole who is my partner in the Tokyo Jazz Joints. He's a broadcaster there and I knew him through some of these jazz dance clubs so I said to him, "what do you think about going around to these places?" I knew he had been to a lot of these places because he had a listing site and recorded these places. If you were in Tokyo and wanted to find a good soul bar or jazz bar you'd go to this site and find the details.

So, we started by going to one place one night and the next thing we'd photograph ten, then twenty, and it just gathered this momentum. As that happened, the identity of the project grew and evolved. During Covid, we started this podcast which brought a new dimension to the whole thing because we had this dynamic and would talk about going to visit these places. We would tell stories behind the photographs I had taken. So it keeps evolving in different directions. It's been kind of fascinating.

AAJ: I found the pictures fascinating and noticed that very few showed people in them and, if they did, it was their backs or with their heads down. Was that intentional?

PA: So, if we're talking about the Tokyo Jazz Joints project it's worth clarifying that in Japan there are jazz clubs for musicians to play jazz in. But the focus of the Tokyo Jazz Joints project is what's known as jazz "kissa" which are basically jazz coffee shops. The term kissa means coffee shop or has come to mean that.

These places sprung up after the second world war. It was partly out of economic necessity because people didn't have any money to buy records or hifi equipment. These guys would open these places and get records whatever way they could, usually off of American troops. They had these high-end audio systems and you would go there and sit, quite often facing the speakers. Traditionally, the furniture would be organized to face the speakers.

You would pay money for your coffee and sit and listen to the latest jazz records. Mostly because it was the only way to hear them or if you wanted to buy one but didn't know which one to buy you could go and choose.

In terms of photographing them, yes, it was a conscious choice. It's easier to photograph in places when there aren't customers. The reality is that a lot of these places aren't that busy anyway. Part of the point of the project is that they're kind of dying off. But as a photographer, yeah, it's a conscious thing to take a moment when someone goes to the toilet and there's a chance to grab a photo quickly.

Equally, if you're taking the backs of people and things like that it gives a sense of someone being in the space. Japan is a very camera-friendly country but there's also things, particularly in jazz places, where people go there to get away from stuff so they don't necessarily want to be photographed. And, also, there's still this sense in Japan around jazz kissa or jazz bars that they have this history of being seen as a bit sketchy and not respectable. So, they don't necessarily want people seeing them in there but that's less of a thing than it used to be.

The whole project has always been about being as unobtrusive as possible because you want to capture the place as best you can so you get a sense of what it's like to be in there. I don't use any flash or a tripod. I just take photos when I can. Part of it is also being respectful of the space so I always ask permission. We go in as customers first and foremost, take a drink, chat with the owner, and once we've established a bit of a rapport we'll say, "would you mind if we took some photographs?"

Sometimes they've heard about the project because we've been doing it for a while. Sometimes they're bemused as to why anyone would want to take a photo of their old dirty place [laughs]. So, it's kind of a mixture of reactions but the idea is to not be intrusive in that way.

AAJ: I see that you've shown your work all around the globe. What has the reception been?

PA: It's been, overall, really positive and encouraging. I think there's a lot of interest in this jazz kissa culture. Part of that has been from the work we've done on this project. There's definitely this awareness now of jazz kissa that's grown. I think that's one of the things that has driven this revival of vinyl and listening bars that you're getting in the States and different cities in Europe, Canada, and Australia. So many people just love Japanese stuff and there are people who love vinyl or who are into jazz. I think there's a lot of intersectionality about the project where all these interests meet. People are always very kind and supportive.

I think the podcast really blew our mind because you get these messages from people from all over the world and the idea that they're just listening to James and I talking shit about some jazz cafe is amazing [laughs]. Then, when we went out for the Kickstarter to raise some money to help with the cost of the book, we had this overwhelming response. We suddenly realized that there's this audience for the project right there. And, since the book and the project has continued, I constantly get messages from people saying, "I'm just going out to Japan and am going to be here. Could you recommend this place or that place?"

There's a real growing interest and that's really nice because it's overlapping with what will eventually be the decline of these places. But it might be that this renewed interest from people outside of Japan might slow that decline down a little bit.

AAJ: I want to go back to the Tokyo Jazz Document which is about the dancers. I love those pictures. How do you capture that intense movement in a still picture?

PA: That's for other people to say if I did [laughs]. It's hard, that's the answer. A lot of it is trial and error because when I started shooting those it was film and then I switched to digital which obviously makes it easier and less wasteful. But it's just hit and miss really because they're moving quickly. Sometimes I use flash and sometimes I don't and it's really dark.

At a couple of the events they were kept quite dark as part of the general atmosphere so it wasn't easy and sometimes photography is just luck. There's one picture on the website but there's probably twenty on either side of it that weren't quite the right one.

Similarly, with the jazz kissa, all of it is just about trying to give some sense of what it's like. But, short of actually being on the edge of that circle and seeing those dancers or being in those jazz kissa, it's really hard to get that fully across. Photography is one way to do it particularly for people who don't have the opportunity to go to Japan or visit one of these clubs.

AAJ: Well, as an American, I have to ask you about your Monochrome 'Murrica pictures. What inspired those and why black and white?

PA: [laughs] Yeah, I don't know. I think a lot of the world has a love-hate relationship with America. Japan definitely does. There's a mixture of fascination, admiration, and revulsion. There's so much familiar and so much that's not familiar. It's not the same as if you go to a country where it's a completely different culture and you don't speak the language. Then, everything is new. But there's so much in America that you get and understand. Plus, we're so bombarded by it in the media so you feel like you know it but when you go there it's kind of what you expect but also very different. You also go and realize that, yes it's a country, but also, it's also just a lot of different countries actually [laughs].

AAJ: You said that some of it was what you expected but some of it you didn't. What didn't you expect?

PA: I think the religious thing fascinates me because I come from a religious background. I come from a country where religion is still a very big thing and runs through everything. There's a sense in America that anything like that is taken to the next degree. It's always bigger and better. There's a photo of a mobile chapel.

I think it's also just the scale of it. In some of those photos I think I was on a road trip in Virginia. We had driven three or four hours and had only gotten halfway down Virginia. Whereas, if you drive from Belfast to Cork, at the bottom of Ireland, it takes you about three hours and then you're just in the sea. I think that scale, even when you do it, is very hard to comprehend. I know to Americans it's quite normal. When Americans come here and say, "we're going to drive from Belfast to Cork," people here are like, "In one day? You can't do that, that's too much driving." And then they ask, "well how far is it?" and we'll say, "about 200 miles." They'll say, "oh ok. That's fine."

I think that's one of the differences. A real dream of mine would be to do a road trip and photograph it. It's been done many times but you can put your own spin on it. Every photographer sees different things and I hope at some point I can do that.

I don't know about the black and white. It's just a stylistic choice actually. It wasn't any conscious thing. Sometimes things pop more in black and white. A lot of those photographs are actually taken on the phone. I was just into that style of editing at the time. Sometimes there's inspiration from Japanese photographers who did that high contrast editing style.

AAJ: What are the parallels in the art of photography and in making music?

PA: Wow. That's a good question. I think when you take a photo you might take it with one intention, but people will see it however they see it. Maybe you're taking it for one thing and they're focusing on something completely different. I tend to take a series of photos and work around a theme but I don't love titles either. I don't really title photos so much other than a basic caption because I think, sometimes, that tends to force people into thinking about it in a particular way. I'm not a musician but I suppose there's an element of that too.

I went to a jazz gig here with a friend who's a musician. It's that thing where he's looking at the drummer, or different instruments, or the different solos being played. He's looking at that and hearing it in a different way than me. Because I'm hearing it with a kind of mystery like, "I wish I could do that but I know I'll never be able to." Whereas he's like, "oh, he did that and played that."

There's also just a freedom in it I think, particularly on the phone. I photograph a lot on the phone. Some projects I specifically use a camera but I think there's a freedom there that you can kind of do what you want and do it in the way that you want. And I suppose, particularly in jazz, a lot of it is about improvisation, right?

Also, looking back at old things with things like the Tokyo Jazz Document and putting it in context. Like I did something recently where I was comparing photographs of the female jazz dancers with the female owners of the jazz kissa. Or, in some cases, the absence of female owners. So, you've got these very central prominent women on the dance floor with the audience and then you've got these female jazz kissa owners who are there but not necessarily visible or not keen to be photographed. So I think, like in music, you can go back and reinterpret things like standards and put your own twist on it.

It's a great question, I've never thought about that.

AAJ: What elements do you think make up a compelling picture?

PA: I think, for me, I see the world almost in frames. I think I see pictures. If I'm walking down the street there's a reason why I would stop and photograph something rather than something else. I mean you could photograph the whole street but you don't. It's not about composing it. When you get the photos back or are editing them, there are certain photos you think, "well, that's not quite right," or "that's a better version." But I think, in the moment, it's just things that catch your eye.

In the jazz kissa, for example, I don't go in with a plan of obsessively photographing the whole place. There will be something that will stand out like a signed Elvin Jones poster that is slightly ripped on the toilet door. There are just those kinds of things. I think that, for me, that's what makes it compelling. Whether that makes it compelling for other people, again, I don't know. You're not shooting for other people necessarily. This project, Tokyo Jazz Joints, was never for anyone else. The idea was to document these places. The fact that people like the photographs and have been very complimentary about the book is a bonus because other people can enjoy them.

But I think, for me, what makes them compelling is there is something that makes you stop and say, "I need to photograph that," rather than just going in, photographing a load of stuff, and then looking through it and saying, "well, that's quite nice or that's quite good."

AAJ: This is my last question. Do you have any new projects on the horizon or something you're working on now?

PA: Yeah, I'm actually doing a PhD at the moment, part-time. I'm looking at what are known as Orange Halls which are meeting places for the Orange Order which is a male, religious organization that started in Ireland. It does exist in other parts of the world that are, or were once, parts of the British Commonwealth, particularly in Canada, and less in Australia and New Zealand.

I'm looking at these buildings because they're quite unusual. They're very plain and very odd buildings. They have certain features that you wouldn't expect in a building that is used like that they have doors and windows that are blocked up. They're very heavily fortified because, quite often, they're under attack.

What I'm looking at with those is this idea that those are buildings that are part of my inherited culture as a Protestant but I don't have any particular interest in going inside or being involved with the organization. It's this idea of being a cultural insider on paper but actually feeling like you're on the outside. I photograph them from the outside.

At some point, there might be a comparison with the jazz cafes because I'm a cultural outsider because I look like this [laughs]. I'm actually on the inside photographing and looking out so I think that's an interesting comparison, just looking at ideas of belonging, feeling at home, and the sense of identity.

And, I just got some funding to do a project around, what we call, "Chinese takeaways." In Northern Ireland there's never been a lot of immigration until, I suppose, the late '90s when "The Troubles" [low-intensity civil war—ed.] eased and people started to come. But there's always been a very strong Chinese community and it's not necessarily highly visible in public life. But, no matter what sized village you go to, there will always be a church and there will always be a Chinese takeaway [laughs].

So, I'm quite interested in photographing those as well as part of the architecture of towns and villages but also, so integrated, that nobody notices anymore. Or, they're not viewed as different or other.

AAJ: Good luck with your PhD!

PA: Yea, thank you [laughs].

Tags

Chats with Cats

B.D. Lenz

Ireland

London

Kyoto

Cork

Elvin Jones

Philip Arneill

Tokyo Jazz

Tokyo Jazz Joints

kissa

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.