Like a Nathan's hot dog or Carvel ice-cream cone, Phil Schaap is a New York original. For the uninitiated, Phil, 59, is best known as the host of Bird Flight, a radio show on WKCR that's devoted to Charlie Parker. But that isn't really what's remarkable. What's special is Phil's unrivaled passion for the subject, his nitty-gritty knowledge, and the fact that the show has been on the air every weekday from 8:20 to 9:40 a.m. since 1983. Many people who know about Charlie Parker and his music gained their smarts and appreciation through Phil's show.

In honor of Parker's 90th birthday on August 29 and WKCR's “Charlie Parker Birthday Broadcast" on the August 28 and 29, I decided to pose five Parker questions to Phil. In today's post, we focus on the famed Ko-Ko session of November 26, 1945:

JazzWax: What's the major artistic achievement of Parker's Ko-Ko?

Phil Schaap: For Charlie Parker, he is in the studio for his first session as a leader. He also is mapping out for you precisely what came to him while playing over Cherokee's chord changes. It's a eureka moment for him in terms of where jazz might be going. He's returning to a piece that was so essential to his development. Through the music, Parker is returning to Cherokee and telling you how the new music—bebop—came to him. [Photo by William P. Gottlieb, Library of Congress]

JW: Returning to Cherokee?

PS: At the time in November 1945, very few people would have been aware that Bird had played Cherokee regularly as far back as 1939. They also wouldn't know that it's through this song that Parker saw the door open for what would become bebop. Ko-Ko is the pinnacle of what this new form of expression is all about.

JW: How so?

PS: Parker is being explicit and inventive about something listeners understood—the reinvention of a popular standard. He is specifically saying through his playing that Ko-Ko is the same as Cherokee but also quite different. During the recording, he also hits the three emphasis points of bebop.

JW: What are they?

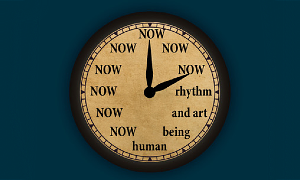

PS: The exhibition of unbelievable amounts of technique almost casually displayed. The incredible wisdom in deep harmony that is effectively displayed through improvisation. And the unleashing of a new rhythmic arc through phrasing, meaning the music now has a completely different feel and sound than swing, which preceded it. The last of the three emphasis points—the rhythmic arc and phrasing—actually is bebop's biggest innovation.

JW: Yet there's also enormous urgency and a mysterious feel to what Parker plays on the intro and outro to Ko-Ko.

PS: Not as much as you think. Yes, there's a radical quality to Ko-Ko that comes from the new rhythmic line. And the song's initial minor key is telling you the music has a different flavor. But that's not what makes this song special. That's just the employing of a fetching component of music's making. The rhythmic line—independent of key or anything else—is an incredibly new way of making music. It's the definitive element of breakthrough, and it's why virtually anyone even casually familiar with jazz can hear that something new is going on in the music.

JW: Then what is Parker saying here?

PS: The music we hear on the record is more important than any hidden meaning Parker may have had. What's most interesting about this session, in some ways, is that Bird had no intention of recording Ko-Ko at the outset.

JW: What do you mean?

PS: This was his first session as a leader, which meant he was responsible for the song choices and choosing the band members. He originally planned to record two blues—Now's the Time and Billie's Bounce, both in F concert—a ballad based on Embraceable You and a tune based on I Got Rhythm's chord changes, which we now know as Anthropology.

JW: What changed?

PS: On a break early in the recording session, Parker went downstairs to pick up his instrument from the repair shop. When he returned, before recording again, he tested the repair by playing the most ambitious piece in his repertoire in terms of technique—Cherokee.

JW: How did this exercise become a recorded song?

PS: Oddly enough, Savoy owner Herman Lubinsky [pictured], who for the most part was non-artistically oriented, heard what Parker was doing and said, “Hey, man, that's what we should record!" Bird agreed and the group recorded Warming Up a Riff and Ko-Ko, both of which were based on Cherokee. They scrapped the I Got Rhythm tune and dropped Embraceable You at the end to make room for Ko-Ko.

JW: Why cut one of the songs?

PS: According to the rules of the musicians' union at the time, you could only record four tracks in one session. This rule was put in place to keep record companies from overworking musicians. When Parker and the musicians pick up Ko-Ko, Dizzy had to play the trumpet part. Miles wasn't going to be able to play that difficult passage at the beginning of the song in 1945.

JW: What happens at the session?

PS: The group recorded three takes of Billie's Bounce. Then they took a break to let Bird go to the repair shop to pick up his alto saxophone. When he comes back, they record Warming Up a Riff, which is based on Cherokee. They also record takes No. 4 and 5 of Billie's Bounce, followed by four takes of Now's the Time and three takes of Thriving From a Riff. There's only take of Embraceable You, known as Meandering. But eventually the last song is dropped for Ko-Ko, the fifth title recorded that day.

JW: Is KoKo an extension of anything the group had played earlier?

PS: Yes, Ko-Ko actually is rooted in the astounding display of harmony Parker executed earlier on Warming Up a Riff, on which he takes a three chorus solo.

JW: Is Parker's opening line for Ko-Ko coming off the top of his head or did he have it already down?

PS: It's an arrangement they already had worked out to Cherokee. But instead of playing Cherokee straight, Parker let the arrangement become the melody.

Tomorrow, Phil talks about Parker's trip to the West Coast, the impact he has on California jazz, and his stay at Camarillo State Hospital near Los Angeles between August 1946 and late January 1947.

JazzWax tracks: The five songs recorded during the Ko-Ko session can be found on the Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes at iTunes or here. You'll find the five tunes recorded in November 1945 on the first disc.

JazzWax clip: Here's Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie playing Ko-Ko, with Gillespie on trumpet and piano...

In honor of Parker's 90th birthday on August 29 and WKCR's “Charlie Parker Birthday Broadcast" on the August 28 and 29, I decided to pose five Parker questions to Phil. In today's post, we focus on the famed Ko-Ko session of November 26, 1945:

JazzWax: What's the major artistic achievement of Parker's Ko-Ko?

Phil Schaap: For Charlie Parker, he is in the studio for his first session as a leader. He also is mapping out for you precisely what came to him while playing over Cherokee's chord changes. It's a eureka moment for him in terms of where jazz might be going. He's returning to a piece that was so essential to his development. Through the music, Parker is returning to Cherokee and telling you how the new music—bebop—came to him. [Photo by William P. Gottlieb, Library of Congress]

JW: Returning to Cherokee?

PS: At the time in November 1945, very few people would have been aware that Bird had played Cherokee regularly as far back as 1939. They also wouldn't know that it's through this song that Parker saw the door open for what would become bebop. Ko-Ko is the pinnacle of what this new form of expression is all about.

JW: How so?

PS: Parker is being explicit and inventive about something listeners understood—the reinvention of a popular standard. He is specifically saying through his playing that Ko-Ko is the same as Cherokee but also quite different. During the recording, he also hits the three emphasis points of bebop.

JW: What are they?

PS: The exhibition of unbelievable amounts of technique almost casually displayed. The incredible wisdom in deep harmony that is effectively displayed through improvisation. And the unleashing of a new rhythmic arc through phrasing, meaning the music now has a completely different feel and sound than swing, which preceded it. The last of the three emphasis points—the rhythmic arc and phrasing—actually is bebop's biggest innovation.

JW: Yet there's also enormous urgency and a mysterious feel to what Parker plays on the intro and outro to Ko-Ko.

PS: Not as much as you think. Yes, there's a radical quality to Ko-Ko that comes from the new rhythmic line. And the song's initial minor key is telling you the music has a different flavor. But that's not what makes this song special. That's just the employing of a fetching component of music's making. The rhythmic line—independent of key or anything else—is an incredibly new way of making music. It's the definitive element of breakthrough, and it's why virtually anyone even casually familiar with jazz can hear that something new is going on in the music.

JW: Then what is Parker saying here?

PS: The music we hear on the record is more important than any hidden meaning Parker may have had. What's most interesting about this session, in some ways, is that Bird had no intention of recording Ko-Ko at the outset.

JW: What do you mean?

PS: This was his first session as a leader, which meant he was responsible for the song choices and choosing the band members. He originally planned to record two blues—Now's the Time and Billie's Bounce, both in F concert—a ballad based on Embraceable You and a tune based on I Got Rhythm's chord changes, which we now know as Anthropology.

JW: What changed?

PS: On a break early in the recording session, Parker went downstairs to pick up his instrument from the repair shop. When he returned, before recording again, he tested the repair by playing the most ambitious piece in his repertoire in terms of technique—Cherokee.

JW: How did this exercise become a recorded song?

PS: Oddly enough, Savoy owner Herman Lubinsky [pictured], who for the most part was non-artistically oriented, heard what Parker was doing and said, “Hey, man, that's what we should record!" Bird agreed and the group recorded Warming Up a Riff and Ko-Ko, both of which were based on Cherokee. They scrapped the I Got Rhythm tune and dropped Embraceable You at the end to make room for Ko-Ko.

JW: Why cut one of the songs?

PS: According to the rules of the musicians' union at the time, you could only record four tracks in one session. This rule was put in place to keep record companies from overworking musicians. When Parker and the musicians pick up Ko-Ko, Dizzy had to play the trumpet part. Miles wasn't going to be able to play that difficult passage at the beginning of the song in 1945.

JW: What happens at the session?

PS: The group recorded three takes of Billie's Bounce. Then they took a break to let Bird go to the repair shop to pick up his alto saxophone. When he comes back, they record Warming Up a Riff, which is based on Cherokee. They also record takes No. 4 and 5 of Billie's Bounce, followed by four takes of Now's the Time and three takes of Thriving From a Riff. There's only take of Embraceable You, known as Meandering. But eventually the last song is dropped for Ko-Ko, the fifth title recorded that day.

JW: Is KoKo an extension of anything the group had played earlier?

PS: Yes, Ko-Ko actually is rooted in the astounding display of harmony Parker executed earlier on Warming Up a Riff, on which he takes a three chorus solo.

JW: Is Parker's opening line for Ko-Ko coming off the top of his head or did he have it already down?

PS: It's an arrangement they already had worked out to Cherokee. But instead of playing Cherokee straight, Parker let the arrangement become the melody.

Tomorrow, Phil talks about Parker's trip to the West Coast, the impact he has on California jazz, and his stay at Camarillo State Hospital near Los Angeles between August 1946 and late January 1947.

JazzWax tracks: The five songs recorded during the Ko-Ko session can be found on the Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes at iTunes or here. You'll find the five tunes recorded in November 1945 on the first disc.

JazzWax clip: Here's Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie playing Ko-Ko, with Gillespie on trumpet and piano...

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.