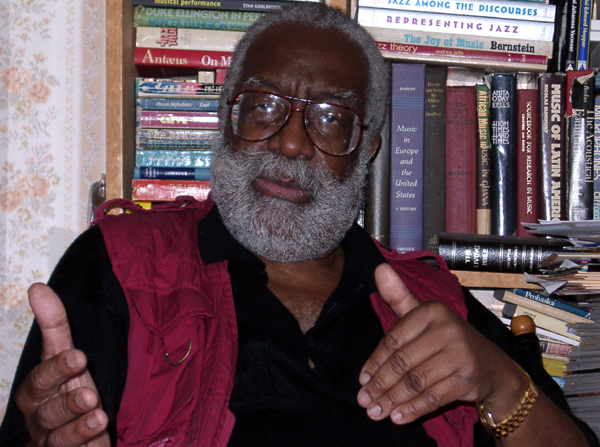

Right now I'm listening to Berlin Abbozzi, a disc recorded in 1999 for FMP by Bill Dixon, who would have turned 85 today (or yesterday, depending on what time zone you're in). Here he plays trumpet and flugelhorn along with utilizing electronic delay, and he's joined by then-regular collaborator, English percussionist Tony Oxley, and the German bassists Klaus Koch and Matthias Bauer. In the pantheon of Dixon recordings, it's not one I listen to often, and I'm not exactly sure why. It has the elements structurally and conceptually of discs I turn to more often, like Vade Mecum I and II (Soul Note, 1994-1996) and November 1981 (Soul Note, 1982). But Berlin Abbozzi either hadn't immediately struck, or more likely I didn't do the work necessary to open up to this particular document. So, I'm acquainting myself anew with this disc and its three compositions. There certainly won't be another performance like this, and whether one prefers it over something else isn't important. Bill Dixon is quite the opposite of Eric Dolphy—once the music has been made (recorded or not), it's there to be judged or not, dealt with or ignored, but whatever the reaction, its literal and ethereal presence can't be denied. The hopeful choice is continued and refined engagement as an open listener.

There is one more new Bill Dixon record slated to come out on Victo by the end of the year, documenting the May 2010 performance of Tapestries for Small Orchestra at the Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville, less than one month before his passing. There will likely be a number of archival releases in the future, though how that exactly manifests itself remains to be seen. Eagerly awaiting another of his releases (as much as they were timed documents of constant work) isn't an impulse that can be stopped, but its parameters have changed. To a related end, Dixon was more than a musician-composer and instrumentalist; he was among other things a painter, writer, organizer, producer, tenured professor/educator, and photographer (the order can be shuffled as one sees fit). There is, in other words, a lot to celebrate and be mindful of when both studying his music and this music, as well as going about one's day as a responsible and creative individual.

Ben Young's annual WKCR broadcast celebrating Dixon's birthday was the first to take place without the master's literal presence on Earth. Young deftly took a small slice of Dixon's work occurring in the early to middle 1980s, mostly in trio formation with bassist Mario Pavone and drummer Laurence Cook, as well as slightly larger lineups with bassists Jon Voigt, William Parker and Peter Kowald, and alto saxophonist Marco Eneidi. The subtle thing about this program was that Young centered the performances not only in a certain time period, but also spatially. They were mostly recorded in the Northeast—Vermont, upstate New York, Connecticut, basically not particularly far from his Bennington home or, for that matter, the university environment.

With creative music a localized struggle, it's often placed on an international scale, showing the breadth of global connections between individual practitioners. It helps that struggle seem less painful through its universality, which builds upon connection and community. (One also sees it in Facebook and Twitter, finding the words and music of Dixon and other artists carried across the globe in a space that transcends virtual and concrete space.) But spending so much time on the idea of this music as “world music" can shirk the locality of one's life and work—ultimately, one is dealing with a tangibly micro space well within the global space. Stephen Haynes has written about this quite extensively on his blog; we spoke tonight and I was again reminded of his fellow brass instrumentalist and improvising composer Taylor Ho Bynum's bike tour through the Northeast recently, where gigs were set up within cycling distance of one another.

Local music and local thought is interesting, because it STILL depends on where you are. On a related but slightly separate note, I often find myself lamenting what I can do as part of the community I feel most connected with, which is quite far from where I call home (central Texas). Would I feel more local becoming an ironically non-local in the Northeast, Chicago, the Bay Area or Berlin? Austin has a vibrant music scene, though creative music gets an extremely small piece of the pie (no surprise) and sometimes seems as barren as a parking lot in Texas heat. It's a community I'm part of, but the resulting local experience is decidedly off the beaten track. A true engagement of space and the feeling of that space is a heady challenge.

The global versus local structure of experience has a direct parallel in accessing an oeuvre as large and diverse as Bill Dixon's. One can't take it all in with a single recording, expecting to divine some sort of universal knowledge by listening to all of his records. Even if you have, at your fingertips, the entire archive of his work (recorded, written, painted, etc.) the waters will still be difficult to navigate. One has to take a piece of it and deal with it in the moment (or as close to the narrow-immediate as possible), as I'm doing with Berlin Abbozzi. As Dixon would say, “you start from where you are. You'll get to the rest in time."

Happy Birthday, Bill.

There is one more new Bill Dixon record slated to come out on Victo by the end of the year, documenting the May 2010 performance of Tapestries for Small Orchestra at the Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville, less than one month before his passing. There will likely be a number of archival releases in the future, though how that exactly manifests itself remains to be seen. Eagerly awaiting another of his releases (as much as they were timed documents of constant work) isn't an impulse that can be stopped, but its parameters have changed. To a related end, Dixon was more than a musician-composer and instrumentalist; he was among other things a painter, writer, organizer, producer, tenured professor/educator, and photographer (the order can be shuffled as one sees fit). There is, in other words, a lot to celebrate and be mindful of when both studying his music and this music, as well as going about one's day as a responsible and creative individual.

Ben Young's annual WKCR broadcast celebrating Dixon's birthday was the first to take place without the master's literal presence on Earth. Young deftly took a small slice of Dixon's work occurring in the early to middle 1980s, mostly in trio formation with bassist Mario Pavone and drummer Laurence Cook, as well as slightly larger lineups with bassists Jon Voigt, William Parker and Peter Kowald, and alto saxophonist Marco Eneidi. The subtle thing about this program was that Young centered the performances not only in a certain time period, but also spatially. They were mostly recorded in the Northeast—Vermont, upstate New York, Connecticut, basically not particularly far from his Bennington home or, for that matter, the university environment.

With creative music a localized struggle, it's often placed on an international scale, showing the breadth of global connections between individual practitioners. It helps that struggle seem less painful through its universality, which builds upon connection and community. (One also sees it in Facebook and Twitter, finding the words and music of Dixon and other artists carried across the globe in a space that transcends virtual and concrete space.) But spending so much time on the idea of this music as “world music" can shirk the locality of one's life and work—ultimately, one is dealing with a tangibly micro space well within the global space. Stephen Haynes has written about this quite extensively on his blog; we spoke tonight and I was again reminded of his fellow brass instrumentalist and improvising composer Taylor Ho Bynum's bike tour through the Northeast recently, where gigs were set up within cycling distance of one another.

Local music and local thought is interesting, because it STILL depends on where you are. On a related but slightly separate note, I often find myself lamenting what I can do as part of the community I feel most connected with, which is quite far from where I call home (central Texas). Would I feel more local becoming an ironically non-local in the Northeast, Chicago, the Bay Area or Berlin? Austin has a vibrant music scene, though creative music gets an extremely small piece of the pie (no surprise) and sometimes seems as barren as a parking lot in Texas heat. It's a community I'm part of, but the resulting local experience is decidedly off the beaten track. A true engagement of space and the feeling of that space is a heady challenge.

The global versus local structure of experience has a direct parallel in accessing an oeuvre as large and diverse as Bill Dixon's. One can't take it all in with a single recording, expecting to divine some sort of universal knowledge by listening to all of his records. Even if you have, at your fingertips, the entire archive of his work (recorded, written, painted, etc.) the waters will still be difficult to navigate. One has to take a piece of it and deal with it in the moment (or as close to the narrow-immediate as possible), as I'm doing with Berlin Abbozzi. As Dixon would say, “you start from where you are. You'll get to the rest in time."

Happy Birthday, Bill.