Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » My Life in the Key of E

My Life in the Key of E

My Life in the Key of E: A Memoir

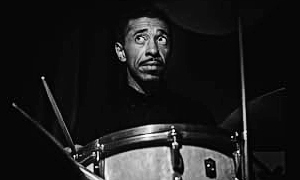

My Life in the Key of E: A MemoirPete Escovedo with Sarah Spinner Escovedo

284 Pages

ISBN: 978-0-692-87885-9

2017

It's not news that the music business is tough.

There are some phenomenally talented people who scuffle for years trying to pay the rent. And, yes, there is the other phenomenon too,a commercially successful mediocrity elevated by the vagaries of popular taste. If for no other reason, Pete Escovedo's memoir makes for interesting reading: he's seen both up close. Throw in an impoverished childhood, issues of ethnicity and race, even East versus West Coast jazz, and you have a story. It's not always edifying or uplifting, but then again, real life isn't either.

Escovedo came from a family from Saltillo, in Northern Mexico, whose origins and motives for migration are understandably murky. Given the date of his father's birth and probable departure from Mexico, one suspects that the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) likely had something to do with with it, but that's just a guess. Escovedo had a hardscrabble childhood, pretty rough even by the standards of immigrant hardship stories. He and his siblings were separated, his Mother raising Pete and a brother, until she could no longer decently provide for them. His father, probably alcoholic, was frequently absent physically. or otherwise.

Escovedo and his brother Thomas ("Coke," as in the beverage, not the drug) ended up in St. Vincent's Home for Boys, "a place where orphans and foster kids stayed because they had no real home." (p. 26) There was, it seems, thank God, no physical abuse—other than the standard growing-up-Catholic-in the-1950s war stories. Yet the brothers were emotionally bereft and deeply scarred by the whole of the trauma. Escovedo implies that his drive to succeed came from his compensating from these childhood experiences, of which St. Vincent's was merely one. There's also little doubt that his strong affection and loyalty to family—and his own growing family after he married—was rooted in the time he spent separated from his birth family. Escovedo was part of a culture in which family was frequently the only safety net and refuge to which one could turn. The value he came to place on spending time with his own family is, in this context, hardly surprising.

Growing up in the East Bay, Escovedo was athletic, gifted artistically (the book features a attractive portfolio of his very impressive Picasso-Modigliani-Cubism inflected work which I suspect any serious collector would value) Percussion came in a fit of absence of mind, and his formal training, apart from on-the-job learning and "great tradition" lessons from storied Latin players like Tito Puente, a lifelong friend, was scarce. Perhaps it's no surprise that he was self conscious and insecure about his playing, which he considered no better than average on timbales. He regarded his brother, Coke, as much superior.

Apparently Carlos Santana did too, because he hired Coke first, then Pete, by virtue of Coke's recommendation. Santana was the big time, with big venues, big crowds and big living. Santana eventually fired both Coke and Pete, but still gets a warm acknowledgment. "It all worked out for the best, Carlos, gracias amigo. (p. 163)

The Santana connection in itself is interesting, because the the Santana story involved a romantic connection with Sheila E, Pete's eldest child, who gradually assumes a much larger role in the story. Sheila moves up from a kid conga player and student violinist to a major pop star in her own right as well as Prince's consort and controvertible heir. Escovedo seems alternately proud of and puzzled by Sheila over the course of the years. In some ways, Escovedo is an old-fashioned Mexican-American paterfamilias, worried about his children's marriages (or lack of them), their well being, and his grandchildren. Escovedo seems a little uncomfortable with modern mores, even returning in the end to the Roman Catholic Church for Sunday Mass. Yet if Sheila and Tito Puente upstaged him at times, he clearly doesn't mind. Escovedo is not a big ego, which is one of the elements that makes his memoir so poignant. He suffers through a succession of failed clubs in the East Bay; watches drugs and booze destroy his beloved brother, Coke; loses old friends as he ages; and assumes more than he share of responsibility for the troubles that life visits on everyone. This is a portrait of a sensitive, vulnerable, and very human person from whom thoughts of God, mortality, and fate are never too distant. And an appealing picture it is.

One of the more intriguing parts of the story concerns the creation of the band Azteca, whose name Pete Escovedo coined even though he, by his own admission, "wasn't trippin [sic] on the race thing." (p. 55) Azteca was Coke's idea, inspired by his time with Santana.

It's not as if Azteca was the only well known band to come out of Oakland. Tower of Power had been hitting since 1968, and still is, but doesn't seem to exist here. Even though Escovedo downplays much if any connection to ethnicity, West Oakland, long since demolished by freeways and "urban renewal" had been home to a thriving Mexican-American community. There is a sort of veiled reference to the political ferment of the 1970s in photographs where Escovedo is pictured with Angela Davis and Dolores Huerta. How much of the Chicano movement fed into the rise and demise of Azteca is not even a small part of the story. Which is a pity, because in 1972, the choice of the name Azteca for a band was by no means a politically neutral one. The East Bay in the 1970s was one of the most radical communities in the United States, and its members, one recalls, were not messing around. As Pete Escovedo tells it, Azteca failed mostly because of Coke's mismanagement and personal problems. Who's to argue with him? But one does wonder how Azteca fit into the radical Chicano movement there.

Of course, this is a personal memoir and, in many ways, a family story. Not everything is about race, class and ethnicity, let alone politics. Yet it would be interesting to situate Escovedo's moving narrative in just such a context, if only to add and to explicate its emotional power, richness, and historical value to a younger generation of listeners for whom Escovedo's story is completely unfamiliar, and for whom there is no suitable context. That story, I suspect, remains to be told.

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.