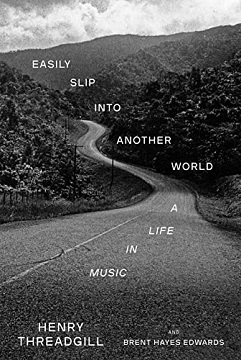

Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life In Music

Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life In Music

Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life In Music

Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life In MusicHenry Threadgill and Brent Hayes Edwards

403 pages

ISBN: #9781524749071

Alfred A. Knopf

2023

Describing Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life In Music as an autobiography of a jazz musician misses the mark by a wide margin. Better to say that Henry Threadgill—regarded by many as an integral part of the jazz tradition—is a significant composer whose work from the 1970s to the present defies categorization. His prodigious output variously references jazz, European classical traditions, and other music worldwide. To give you an idea of the breadth of his interests and history, Threadgill once invented an instrument, the hubkaphone, in part inspired by gong bands of the indigenous mountain tribes whom he encountered while enduring a hazardous tour of duty during the war in Vietnam.

A 2016 winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Threadgill is something of a quicksilver figure in modern music, persistently following his muse wherever it takes him, leading and eventually dissolving touring and recording ensembles to heed the call of yet another shadowy but ultimately realizable world of sound. Equally at home writing for theater and dance productions, Threadgill has accepted commissions to compose for numerous venues and ensembles of varying sizes and instrumentation. He is (with the assistance of Brent Hayes Edwards) a great storyteller who has traveled the world—often with limited resources—searching for new experiences and plying his skills as a professional musician. Perhaps most importantly, he offers insights into what it takes to consistently make creative music without the barriers imposed by stylistic conventions and institutional expectations.

Threadgill's childhood and adolescence in Chicago abounded with music. The radio in his home was a constant presence, offering a stunning array of sounds: classical, Serbian, Polish, Mexican, country, jazz, rhythm and blues, gospel, and more. Studs Terkel's show was a favorite, featuring music, interviews with figures from many walks of life, and glimpses into a larger world. A local record store that blared the music into the street introduced Gene Ammons, the first of several Chicago jazz tenor men to grab Threadgill's attention. Live music was plentiful, from the two churches his family attended and blues on Sunday mornings in the Maxwell Street Market to concerts in movie houses and theatres.

Indications of the depth of the young Threadgill's interest in music are plentiful. He reports being stunned by a Sunday morning performance by Howlin' Wolf. ..."the power of his sound almost had me frozen in my footsteps." During nap time in the classroom, one of his teachers played classical music records. Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony "was just like Howlin' Wolf—it would take me off." Recordings by Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and others in his father's jazz-only jukebox made him "lose all sense of my surroundings: I wouldn't even be there; I would be gone." To the future composer, these records spurred an interest in ..." decipher[ing] the secrets of the songs' pulsating architecture."

The wonders of making constant musical discoveries didn't shield Threadgill from the ugly, unrelenting and often lethal realities of racism. During a brief period when he committed petty crimes with some of his youthful peers, the police simply shot at him rather than give chase. Eventually, he realized that his white friends did not have to dodge bullets for indulging in "some minor nonsense." Threadgill struggles to process photographs in Jet magazine of the mutilated body of Emmett Till, a childhood acquaintance. "What was I supposed to do with that? Where was I supposed to tuck it away?" Then there was an attack on Threadgill and a friend by a brick-throwing mob of adults because of the boys' accidental crossing of an "invisible line" into an all-white neighborhood. "We simply couldn't understand it. And we knew, without even discussing it, that there was no one we could talk to."

Early attempts at making music included playing boogie-woogie piano by ear at home. Quickly abandoning piano lessons with a teacher who inflicted physical punishment for mistakes, he stayed with the instrument and made discoveries independently. Threadgill's penchant for figuring things out without the help of his elders thrived in the context of getting together with friends and, for their entertainment, memorizing and singing every part of songs off of jazz records. Although he eventually acquired a tenor saxophone, took private lessons with several teachers, studied formally on a college level, and earned a degree in composition from a conservatory, he contends, "You had to know far more than what the teachers are telling you." And ..."you have to take over as your own instructor and find your own way."

Unlike practical "instruction in the courses, from species counterpoint to orchestral arranging and conducting," Threadgill's schooling in the black music tradition did not take place in a college or conservatory program. "You have to come to the tradition on your own terms," he asserts, in the company of friends, learning standards on your own, and making music at churches, funerals, parades, parties, and school dances. He would sneak out from home at night and make the rounds of the robust Chicago jazz scene, taking in the sounds and, when the time was right, asking questions. While admiring and studying the methods of several Chicago jazz tenor players, Threadgill stopped short of playing "someone else's solo." He cautions against transcribing and learning specific improvisations by heart because literal imitation is "to contaminate yourself." ..." don't steal that stuff because it's powerful."

Another of Threadgill's bedrock principles is "Failure Is Everything." (At one point, he considered using it as the book's title.) He regards failure as inevitable and uses it as a spur to improve his musicianship and avoid getting stuck at a certain level of competence. "I realized early on that I wasn't going to be content to stay where I was." While in high school, he received an invitation to play in a rehearsal big band comprised of experienced, professional musicians; unfortunately, he could not deal with the music. Out of desperation, Threadgill stayed in his mother's basement all summer, practicing day and night in hopes of making a triumphant return. Eventually, he came back, began to cope with the band's sophisticated arrangements, and learned the art of section playing.

Getting a foothold in establishing an identity as a composer was a long, arduous process, beginning in his senior year of high school. Threadgill's abundance of interests and influences left him disinterested in "trying to fit into a particular corner of the landscape." The European classical tradition was to be studied and comprehended, not imitated, and the same applied to the jazz tradition, particularly bebop. His formal music studies gave him the ability to "take music apart and understand it," but a desire to keep established styles at arm's length in terms of his writing leaves the question of what, if any, model to use.

The answers came in the form of philosophies and attitudes, perhaps more than the substance of the work of three composers: Edgard Varese, Claude Debussy, and Muhal Richard Abrams. Threadgill admired Varese's obstinacy and insistence on not doing what everyone else had done. He held Debussy in high regard for the composer's refusal to worry about the work holding up to the scrutiny of formal analysis. "Don't reject something because you can't explain it." Threadgill briefly played in Abrams's Chicago-based Experimental Band (a precursor to the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, or AACM) and often talked about music with him. He regarded Abrams as a model for the community because he was not "a product of a distinct tradition or an elite institution." "Nothing was off limits; nothing was beyond him." Abrams's example inspired Threadgill to stay focused and strive to produce new and novel work.

The years following his discharge from the army were a beehive of activity in which he drew inspiration from various experiences. The example of his peers in the AACM, some of whom were "working out their own individual musical vocabularies and even their own notational systems," fueled Threadgill's determination to find his way as a composer even as he made a living as a working musician in Chicago. Instead of following the predictable, short-sighted route of taking straight-ahead jazz jobs, he "ended up getting a much broader and deeper musical education" by embracing numerous pick-up and short-term gigs: Theatre and dance work, Brother Jack McDuff, The Dells, Latin ensembles, polka bands, and marching bands. All of these things may have been a circuitous, time-consuming route for a forward-thinking musician and composer, yet Threadgill treated every gig as a learning experience, and often used what he learned in the future.

Determined to be something more than a sideman and itching to compose for his own group, Threadgill forms the trio eventually known as Air, the first of his celebrated working and recording bands. As applies to Threadgill's ensembles into the present day, the exploratory urge still reigns supreme. Writing for the personalities of his saxophones and flute, bassist Fred Hopkins, and drummer Steve McCall, he explores "the tonal possibilities of each instrument," rejects the notion of the soloist and accompaniment dichotomy, expects the music to unfold and change form in rehearsals and performance, and regards the group's efforts as a "radical commitment to the collective statement."

By the mid-1970s, Air had outgrown the opportunities to work in Chicago and the Midwest. Not unlike many prominent black music artists from Chicago, the West Coast, and St. Louis, the trio migrated to New York City, where they regularly played in lofts, apartments, galleries, bars, restaurants, and theatres, toured in the Northeast Corridor and, eventually, the European festival circuit.

Throughout the book, Threadgill cites examples of putting his ideas and projects into motion, making things happen in the performing arts world instead of passively waiting for opportunities to arise. For instance, in the mid-1980s, he initiated the first Great American Music Tour with the Sextett, one of his ongoing ensembles. The band traveled thousands of miles throughout the United States and Canada in a rented motor home; the band members sharing the driving. Threadgill booked some dates in advance; he arranged others on the fly. Clubs in large cities were on the itinerary, as were non-traditional venues such as ..."undergraduate student centers in big universities, municipal art museums, community cultural centers, schoolhouses." In one instance, the Sextett stopped and played for people in the middle of a state park. The constantly changing circumstances during the extended tour positively affected the music, as Threadgill and the group "radically modified the arrangements of some of the older pieces."

At a certain point during the tenure of each of his working ensembles, Threadgill exhausts the creative possibilities. His response is to transition into another, self-conceived world of sound to further his growth as a composer. "To expel myself from my proclivities...sometimes I have to destroy my own process to get to something new." While he is grateful for the commitment of musicians who have given "themselves over completely to the art" and shaped "their lives to prioritize the music," a musical dead-end necessitates breaking up the group, gradually and patiently conceiving another direction and then building a different band to realize the emerging concept.

For all his accomplishments in a lifetime of performing and composing, Threadgill gives the impression that there is no end to his creative endeavors. Clearly, he has no intention of resting on his laurels, and a victory lap is not imminent. Easily Slip Into Another World is a lengthy, stimulating, entertaining, and thought-provoking book.

Tags

Book Review

David A. Orthmann

Alfred A. Knopf

Henry Threadgill

Gene Ammons

Howlin' Wolf

Count Basie

duke ellington

Benny Goodman

Muhal Richard Abrams

Jack McDuff

Fred Hopkins

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.