Home » Jazz Articles » Jazz in Long Form » The Vocal Music of Charles Mingus, Part 2

The Vocal Music of Charles Mingus, Part 2

Making the simple complicated is commonplace; making the complicated simple, awesomely simple, that’s creativity.

—Charles Mingus

Early Years: 1945 to 1953

Charles Mingus demonstrated his prowess as a songwriter even in the early stages of his career. Surprisingly, he started writing songs as early as 1945, a fact that often goes unnoticed. This collection of early vocal compositions includes titles such as "The Texas Hop" (1945), "Baby, Take a Chance with Me" (1945), "Ain't Jivin' Blues" (1946), "Weird Nightmare" (1946), "Pacific Coast Blues" (1948), "Boppin' in Boston" (1949), "I've Lost My Love" (1952), "Make Believe" (1952), "Paris in Blue" (1952), "Portrait" (1952), "Eclipse" (1953), and "The Edge of Love" (n.d.).Vocalist Glòria Vila delved deep into these early works as part of her master thesis titled Charles Mingus: recopilación y análisis de su repertorio vocal (Charles Mingus: collection and analysis of his vocal repertoire). Her research uncovered the significance of these compositions within Mingus' body of work, drawing insights from Brian Priestley's influential book Mingus: A Critical Biography (1982). In the book, Priestly highlights Mingus' aspiration to establish himself as a songwriter during these formative years. Driven by his poetic talent and the need to provide for his family, Mingus saw songwriting as a potentially lucrative avenue alongside his non-commercial music pursuits. Vila astutely observes:

"This could be a key factor in explaining the distinct character of some of these early pieces and their divergence from the familiar musical landscape associated with Mingus. Whether it was due to his youthful perspective, early career ambitions, or the prevailing musical trends of the time when these compositions were conceived, many of these works stand in contrast to his future contributions."

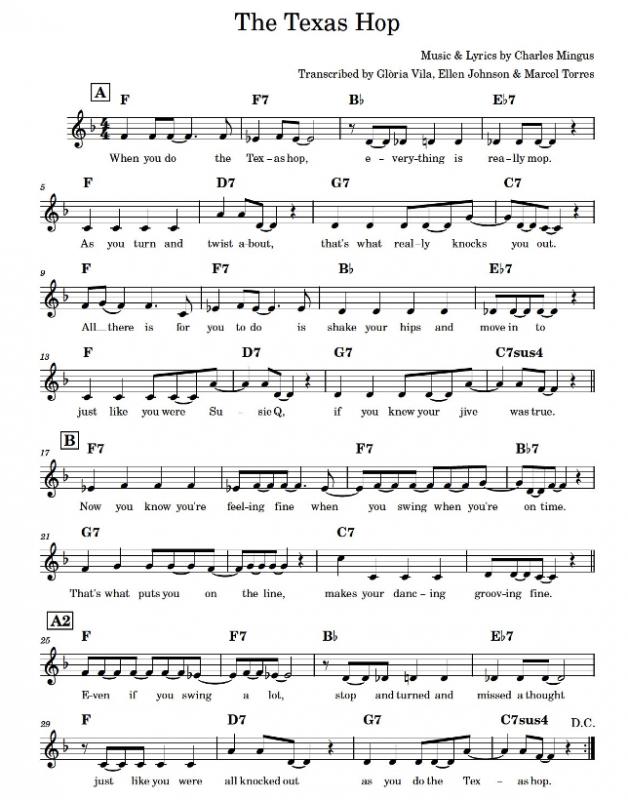

A compelling comparison can be drawn between the simplicity of "The Texas Hop," (sung by Oradell Mitchell) characterized by lively dance rhythms and playful jive lyrics, and the lyrical intensity and intricate harmonies of "Weird Nightmare," composed merely one year later.

As we approach the 1950s, Mingus's musical vision begins to reveal a stronger influence from luminaries such as Duke Ellington, classical music influences, complex harmonies, and improvisational leanings, which also manifest in the lyrics, often delving into the realm of ideological expressions. According to Vila, "In addition, we come across blues compositions within this early repertoire that adhere closely to the conventional harmonic and structural patterns of the traditional form, exemplified by "Ain't Jivin' Blues," "Pacific Coast Blues," and even "The Texas Hop" itself. However, surprisingly, amidst this early material, one can discover highly representative pieces that foreshadow Mingus' mature musical work, eventually becoming the ones he revisited and re-recorded numerous times, such as "Weird Nightmare," "Portrait," and "Eclipse."

However, it should be noted that not all these early songs cannot be unequivocally attributed to Mingus alone, as he collaborated with other musicians in their creation. Vila clarifies:

"While we can ascertain Mingus's involvement in the composition of these early songs to some extent, the degree of his contribution remains uncertain. It is plausible that Mingus solely composed the music, with the lyrics subsequently crafted by the singers, without providing proper credits. We do know that he co-wrote several pieces with other individuals, such as Jack Griffin on "The Texas Hop," Jesse Cryo on "Ain't Jivin' Blues," and Will Baranco on "Pacific Coast Blues." These collaborative endeavors appear distinct within Mingus's repertoire, suggesting that such partnerships influenced his artistic adaptability and perhaps shaped the musical direction of these particular songs."

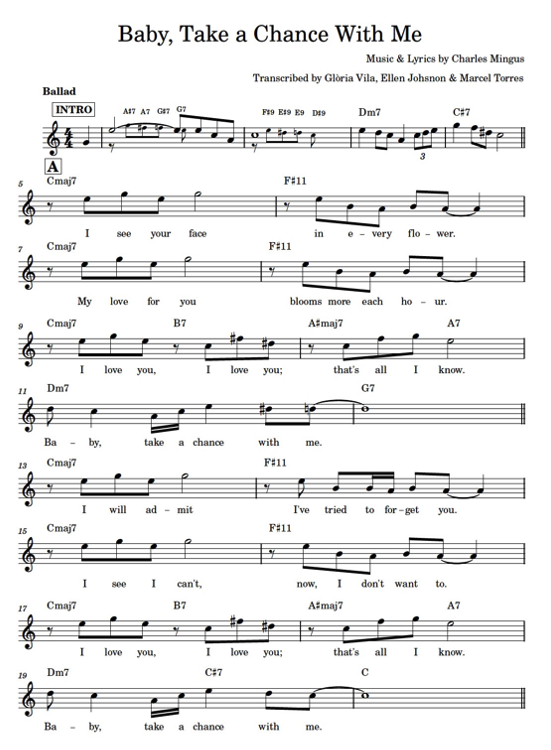

During an interview Vila describes and suggests that there are four exemplary lesser-known songs from this early period that represent Mingus' distinctive elements and characteristic style found in his body of work. The songs include "Baby, Take a Chance with Me," "Make Believe," "I've Lost My Love," and "Paris Blues." Crafted at the tender age of seventeen, "Baby, Take a Chance with Me" stands as a remarkable testament to Mingus' prodigious talent in crafting awe-inspiring ballads, adorned with impressive melodies and inspired lyrics. The inaugural recording, featuring the soulful vocals of Everett Pettis on "Excelsior" from 1945, offers a poignant glimpse into Mingus' emotional expression and his innate ability to evoke depths of sentiment.

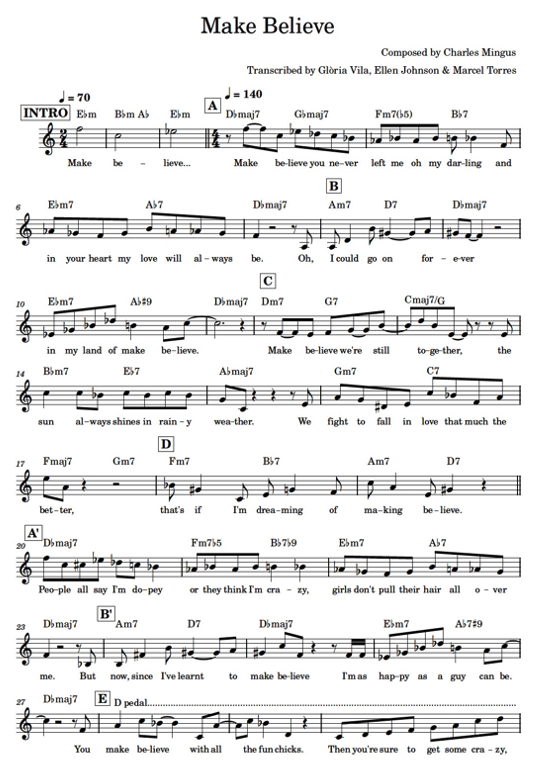

Mingus' exceptional command of harmony and his inventive approach to composition are strikingly evident in the captivating song "Make Believe." The two very different early versions of this song were recorded first on 4 Star Records (1946) sung by Claude Trenier and later Debut Records (1952) by Jackie Paris. These contrasting interpretations offer a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of Mingus' musical vision and the different vocal styles that brought this composition to life.

The poignant rendition of "I've Lost My Love" by Bob Benton in 1952 highlights the impact of classical music on Mingus' artistic growth and expression. This composition captures the essence of a Schubert "lied," infusing it with fervent passion and capturing the essence of heartfelt longing. Mingus' remarkable ability to seamlessly blend classical influences with the vibrant idioms of jazz is on full display, showcasing his unique talent for bridging the gap between these two genres.

Lastly, we have the captivating blues composition "Paris in Blue," sung and dedicated to Jackie Paris on a single and then on Debut Rarities, vol 4 (Debut Records,1952/1990) This song stands as a vivid illustration of an unconventional blues form, showcasing Mingus' propensity for pushing the boundaries of traditional blues form. What sets "Paris in Blue" apart is the emergence of episodic structures, where each episode unfolds with a new tempo change adding an extra layer of intrigue and excitement. Mingus' innovative approach to structure and tempo within this blues composition exemplifies his willingness to explore new musical territories and defy conventional norms.

Vila further underscores the unwavering authenticity of Mingus' artistic essence throughout his journey, stating:

What impressed me most is how he stayed true to his genuine essence throughout his entire career. In these early compositions, even in the most basic ones, one can discern the unmistakable traits of the composer. Mingus exhibited a genuine mastery in distilling complexity into simplicity.

Weird Nightmare and Portrait

Within Mingus's collection of vocal compositions, it is important to highlight that certain songs have achieved notable acclaim and acknowledgement. Specifically, "Weird Nightmare," "Portrait," and "Eclipse" have emerged as standout pieces (for a comprehensive discussion, please refer to Part 1). These compositions have struck a chord with musicians, listeners, and reviewers, contributing to their prominence within Mingus's vocal repertoire. Their impact and resonance have played a significant role in establishing their status among his notable vocal works.Weird Nightmare you haunt my ev'ry dream

Weird Nightmare tell me what's your scheme?

Can it be that you're a part of a lonely broken heart?

Weird Nightmare why must you torment me?

Weird Nightmare pain and misery,

In a heart that's loved and lost,

Take away the grief you caused.

Can't sleep at night,

Twist, turn in fright

With the fear that I'll live it all again,

In my dreams

You're there to haunt me when you say he doesn't want me,

I've been hurt, Do you know what that means?

Weird Nightmare take away this dream you've borne,

Weird Nightmare mend a heart that's torn,

And has paid the price of love a thousand-fold.

Bring me a love with a heart of gold.

Weird Nightmare.

According to the publication Charles Mingus: More than a Fake Book, the recording of "Weird Nightmare" took place in 1946 when Mingus was just twenty four years old, under the small record label Excelsior. It was later recorded again in 1958 for MGM/Verve as part of an album of jazz compositions accompanying a poetry reading by Langston Hughes. Finally, it appeared on the album Pre-Bird (Mercury,1960), with Lorraine Cusson performing the vocals, while the earlier version featured Claude Trenier. An interesting anecdote involves the version featuring Cusson, who accidentally reversed the order of the last line, singing "Bring me a heart with a love of gold" instead of the intended "Bring me a love with a heart of gold." Cusson assumed that Mingus was not displeased enough to risk another take, thus leaving the reversal in the final recording.

Throughout the evolution of "Weird Nightmare," Mingus repeatedly altered its title, experimenting with various names such as "Pipe Dream," "Vassarlean," and "Smooch" when it was recorded by Miles Davis. However, despite these title transformations, the song retained its compelling nature in each rendition. Remarkably, it stands as one of the rare compositions from Mingus' early years that resurfaced in his later recordings and live performances, solidifying its enduring presence within his repertoire. In his book I Know What I Know, Todd S. Jenkins describes the song as "one of the strangest, yet most compelling tunes in the Mingus canon" suggesting that it "must have some particular magic for him." This is noteworthy considering Mingus's usual emphasis on pushing forward as a composer rather than dwelling on his previous contributions. "Weird Nightmare" appears to exhibit influences from Ellington's expressionistic works, while also displaying hints of the musical language employed by classical composer Alexander Scriabin. The bass part requires the player to navigate through all twelve notes of the chromatic scale, pioneering a path through a complex maze of chord progressions within a simple AABA song form, with the option to include a one-measure tag ending or omit it when returning to the beginning of the form.

I've seen all kinds of pictures,

Most of the beauties of the world,

From places I've traveled I still recall

This quaint melody as I thrill,

Painting my own pictures in tones.

I've painted all Mother Earth

Both flowers that brave the morn

Tones color the life she's borne

I've tried to paint her beauties,

From radiant skies to deep blue seas

The sky as she changes her glamour,

Dawn's pale blue, sunset's amber,

The winds and the vains (probably should be: rains)

Leaves on the ground,

Mountains gray brown

Tipped with a dash of glowing white snow.

The next composition was originally entitled "Inspiration" then "God's Portrait" and eventually "Portrait" recorded as a big band arrangement. It appears on Mingus' first self-produced recording for Debut on April 12, 1952, with Jackie Paris as the vocalist on the session. (While the Mingus Fake Book includes the lyric "The winds and the veins" upon careful listening, it becomes evident that Paris is actually singing "The winds and the rains." This correction aligns more coherently with the overall theme and meaning of the composition, as perceived by this author. By making this adjustment, the intended imagery and symbolism behind the lyrics become clearer and more contextually fitting within the song.) Apart from the instrumental versions documented in Mingus discographies, there is a rendition of the composition featuring Thad Jones and a chamber orchestra. Surprisingly, this recording, made in September 1954 for Debut, has not been included in the official Mingus discographies.

The lyrics of "Portrait" were influenced by Mingus's spiritual discussions with Farwell Taylor, which led to the creation of nature-focused imagery.This composition serves as a precursor to a later work, "Duke Ellington's Sound of Love," showcasing similarities in key (Db), rhythmic patterns such as the incorporation of quarter note triplets, tonality, and certain rhyming structures. Stefano Zenni explores this connection from his article, The Music of Charles Mingus in California, 1942-1949: An Analytic Survey, "This the most important key of Mingus' music: it's the key of the "autobiographic" compositions, the "soul key" in which he played by instinct." In the book Mingus Speaks by John F. Goodman, there are recorded conversations with Mingus where he shares his perspective on the use of keys. Mingus boldly expressed, "When a guy tells you all keys are alike, he's a liar." This statement reveals his strong belief in the significance and distinctiveness of different musical keys, emphasizing that each key carries its own unique qualities and characteristics.

While "Portrait" is labeled with section letters (ABCD) in the Mingus Fake Book, its structure effectively functions as a 32-bar ABAC form. However, it is plausible that the use of the ABCD lettering is connected to achieving a specific lyrical outcome rather than strictly adhering to the musical form. Zenni analyzes it further:

..." "Portrait" has a deep motivic unity... we see that that first two-bars phrase appears again in several strategic points... the harmony has a personal touch: the B section keys are C, A-flat and F, a minor third progression written many years before Coltrane's "Central Park West" ...the D section is more dissonant and daring.

Mingus Oh Yeah

Mingus' enduring passion for vocals is evident throughout his illustrious career. One unconventional recording that showcases his unique approach to lyrics and vocals is the dynamic album Oh Yeah (Atlantic, 1962). Mingus, accompanying the group on piano alongside Doug Watkins on bass, unleashes his expressive vocalizing abilities, infusing the music with vibrant bluesy punctuations that serve as a continuous commentary. While not primarily focused on traditional singing, Mingus employs a range of vocal techniques, everything from speaking, singing, scatting, chanting, wailing, shouting and other sounds. These vocal expressions not only convey lyrical content but also ignite the band. According to a review by Steve Huey in All Music, Mingus' vocal selections exude a captivating madness:Mingus' vocal selections radiate the same dementia, whether it's the stream-of-consciousness blues couplets on "Devil Woman," the dark-humored modern-day spiritual "Oh Lord Don't Let Them Drop That Atomic Bomb on Me," or the dadaist stride piano bounce of "Eat That Chicken," a nod to Fats Waller's comic novelties.

In this context, Mingus's vocals embody a remarkable and audacious spirit, showcasing his exceptional ability to mold words, sounds, and singing into a diverse palette of musical colors. Mingus fearlessly experiments with various vocal techniques, weaving them seamlessly into his musical tapestry and pushing the boundaries of conventional vocalization.

Collaborative Lyricism: Contributions to Mingus Compositions

The provided information aims to inspire vocalists and instrumentalists to embrace the abundant vocal repertoire that Mingus has left behind. It is hoped that this knowledge will encourage musicians to explore and engage with these compositions. Mingus's wife, Sue Mingus, has played a critical role in preserving and promoting his music, actively encouraging collaboration with other lyricists to contribute to his body of work. As a result, there have been additional lyrics to instrumental compositions that have received Sue's endorsement, expanding the repertoire available for exploration. While there may be numerous undiscovered lyric gems, the currently recorded songs that have garnered Sue's approval are particularly noteworthy.- A Chair In the Sky (lyrics by Joni Mitchell)

- Dry Cleaner from Des Moines (lyrics by Joni Mitchell)

- Goodbye Porkpie Hat (lyrics by Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Joni Mitchell

- Hora Decubitus (lyrics by Elvis Costello)

- Invisible Lady (lyrics by Elvis Costello)

- Noddin' Ya Head Blues/aka White-Collar Blues (lyrics by Ellen Johnson)

- Noonlight (lyrics by Sue Mingus)

- Nostalgia in Times Square/aka Nostalgia for Mingus (lyrics by Ellen Johnson)

- Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Blue Silk/aka Orange or Blue Silk (lyrics by Ellen Johnson)

- Peggy's Blue Skylight/aka Skylight of Blue (lyrics by Ellen Johnson)

- Slippers/aka Diana's Slippers (lyrics by Ellen Johnson)

- Sweet Sucker Dance (lyrics by Joni Mitchell)

Note: Transcripts of the songs mentioned in both Part 1 and 2 are available here.

Tags

Jazz in Long Form

Kurt Ellenberger

Charles Mingus

Glòria Vila

Brian Priestley's

Oradell Mitchell

duke ellington

Jack Griffin

Jesse Cryor

Will Baranco

Everett Pettis

Claude Trenier

Jackie Paris

Bob Benton

Langston Hughes

Lorraine Cusson

Miles Davis

Todd S. Jenkins

Thad Jones

Farwell Taylor

Stefano Zenni

Steve Huey

Sue Mingus

Joni Mitchell

Rahsaan Roland Kirk

Elvis Costello

Ellen Johnson

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.