Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Roy DeCarava: The Sound I Saw

Roy DeCarava: The Sound I Saw

I’m not a documentarian, never have been. I think of myself as poetic, a maker of visions, dreams, and a few nightmares.

—Roy DeCarava

The Sound I Saw

The Sound I Saw Roy DeCarava

228 Pages

ISBN: 9781644230107

David Zwirner

2019

Roy DeCarava was a jazz photographer, artist and Harlem local who captured everyday life in the Manhattan area with an insider's eye. Through a spare, striking use of natural light, DeCarava's exploration of the aesthetics of blackness was revolutionary, challenging the cultural assumptions around race, poverty and artistic representation that were prevalent in the 1950s and 1960s. His much fêted collection of photography The Sound I Saw, first published in 2001, was reissued in late 2019 by the books division of international art gallerist David Zwirner.

When Columbia Records commissioned DeCarava to shoot the cover photograph for Miles Davis' Porgy and Bess (Columbia, 1959), most sleeve photographers opted for one of two prevailing clichés: a flattering studio portrait or an intense performance shot. But DeCarava wanted something out of the ordinary. The story goes that he pitched up unannounced at Davis' brownstone, to prevent Davis giving too much preparatory thought to the image. Once inside, DeCarava took an informal photograph of Davis sitting next to his girlfriend, the dancer Frances Taylor, in the backyard. Neither of their heads or faces are in the frame. Instead the viewer's gaze is directed towards Taylor reaching out with her left hand to caress the trumpet Davis is holding on his lap. Intimate and sensual, DeCarava's shot perfectly captures the atmosphere of George Gershwin's opera as interpreted by Davis.

Whatever the actual circumstances of the Porgy and Bess shoot, the image is illustrative of DeCarava's idiosyncratic approach to his work. The Sound I Saw—the title chimes interestingly with trumpeter Jon Hassell's Listening To Pictures: Pentimental Volume One (Ndeya, 2018)—features shots De Carava took in and around Harlem over a roughly eight-year period in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Other talented photographers were patrolling the same beat, but DeCarava's approach stands apart. The featured musicians—spanning famous, soon-to-be famous and lesser known names—are variously portrayed onstage, backstage or just hanging out. But they form only part of the book. Their photographs are interspersed with shots of their wives and children, their apartments, the views from their windows, middle-distance shots of passers-by walking down the street; the everyday milieu in which the musicians led their lives.

DeCarava's contextualizing of his subjects adds a depth of meaning rarely found in jazz photography, and it gives his work a power which continues to inspire photographers and film-makers in 2020. But it also fosters a false notion that DeCarava was, first and foremost, a documentary photographer with a social-realist aesthetic. In fact, he deserves to be judged as—and considered himself to be—an art photographer. He rejected the contemporary idea that African Americans were unpromising subjects for art, suited to be portrayed only as caricatures or social problems, and that their depiction should serve either as a lesson in history or an instrument of social change.

"I'm not a documentarian, never have been," said DeCarava in a 1990 interview. "I think of myself as poetic, a maker of visions, dreams—and a few nightmares."

DeCarava was born in Harlem in 1919. After leaving high school, he won a place at New York's Cooper Union School of Art, where he trained to be a painter. After two years, he moved to the Harlem Community Art Center (HCAC), where he redirected his energies towards photography. It was an auspicious move. At HCAC, DeCarava met the writer Langston Hughes, with whom he would later collaborate on his first book, The Sweet Flypaper of Life.

In 1950, DeCarava's photographs came to the attention of Edward Steichen, the director of the Department of Photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). At Steichen's urging, DeCarava successfully applied for a grant from the Guggenheim foundation. In his application, he said that he wanted to devote a year to photographing Harlem and its people "morning, noon, night, at work, going to work, coming home from work, at play, in the streets, talking, kidding, laughing, in the home, in the playgrounds, in the schools, bars, stores, libraries, beauty parlours, churches, etc...[But] I do not want to make a documentary or sociological statement. I want a creative expression."

In 1954, DeCarava and Langston Hughes teamed up to produce The Sweet Flypaper of Life, which was published the following year. The book featured a selection of DeCarava's Guggenheim-funded photographs accompanied by a fictionalized narrative written by Hughes. Encouraged by its success, DeCarava began putting The Sound I Saw together in 1956, although the book was not published in its finished form until 2001.

It was while shooting The Sweet Flypaper of Life and The Sound I Saw that DeCarava perfected the two core signatures of his style—the use of available light rather than flash and an embrace of the dark tones that often resulted from that choice. In 1990, he talked about this approach in an interview with Ivor Miller published by the John Hopkins University Press. "I don't try to alter light, which is why I never use flash," said DeCarava. "I hate it with a passion because it obliterates what I saw. When I fall in love with something I see, when something interests me, it interests me in the context of the light that it's in. So why should I try to change the light and what I see, to get this 'perfect' information-laden print? I don't care about that. The reason why my photographs are so dark is that I take photographs everywhere, light or not. If I can see it, I will take a picture of it. If it's dark, so be it. I take things as I find them because that's the way I am and that's the way I like them. When I went to a jazz club it wasn't lit up like a T.V. studio. It was dark. I accept that."

Later in the same interview, DeCarava said that the use of darker tones could be interpreted as conscious opposition to the values imposed on American society by European tradition—and the resulting sidelining of black culture. "I get a little angry," he said, "with some of my friends who insist that I listen to classical music because it is really music, or that I listen to opera because it is the truth. I say this is simply a European perception. There are other perceptions in the world about music. I happen to find opera very simplistic. I find classical music very rigid, needing almost a slave and master relationship to make music. The conductor is the master, the musicians are the tools with which he forges someone else's music; they do what he wants them to do. To me, the idea of jazz, the right and the need of the individual to express his uniqueness, which is what jazz, and even folk music is about, is also music. I resent the idea that classical music is the only music and that therefore I am suspect, I'm not quite civilized, if I don't embrace it."

In 1996, MoMA mounted a retrospective of DeCarava's work. For an American photographer, a MoMA exhibition is the ultimate art-establishment seal of approval. The recognition had been hard won. Only six years earlier, DeCarava said to Ivor Miller: "I will never get credit, I think, for my ability as a photographer. [They say] I'm black first, which puts me in another category. I don't know how many times I've been called 'one of the great black photographers,' but that's not as good as a plain white photographer."

"The MoMA exhibition was accomplished by the dint of many dedicated individuals, some from outside the normal museum curatorial structure, as well as by the feeling that 'the time had come' from the context of a broad artistic truth," said Sherry Turner DeCarava, an art historian DeCarava married in 1971, in an interview in 2017.

"Roy set a standard for excellence that remains unmatched. Yet in the years since, despite the collective best efforts of supporters and friends, he has not had a book published or a major solo exhibition. This has remained an enduring frustration even as his work continues to speak to who we are as human beings and continues to inspire generations of artists. The hands of museum directors, publishers and curators are completely clean. Don't you find this odd? As an observer, I do.

"But the truth of Roy DeCarava is carried from hand to hand and heart to heart, despite the fact that so much of his work remains unpublished and all of his books are out of print. The world needs Roy DeCarava so we may better understand beauty and justice as an undivided expression. The recognition and mystery of that experience is where we find ourselves, reflected through the lens of his artwork."

Roy DeCarava passed in 2009.

The republication of The Sound I Saw is something to celebrate. It is sad that its creator is no longer around to hear the applause.

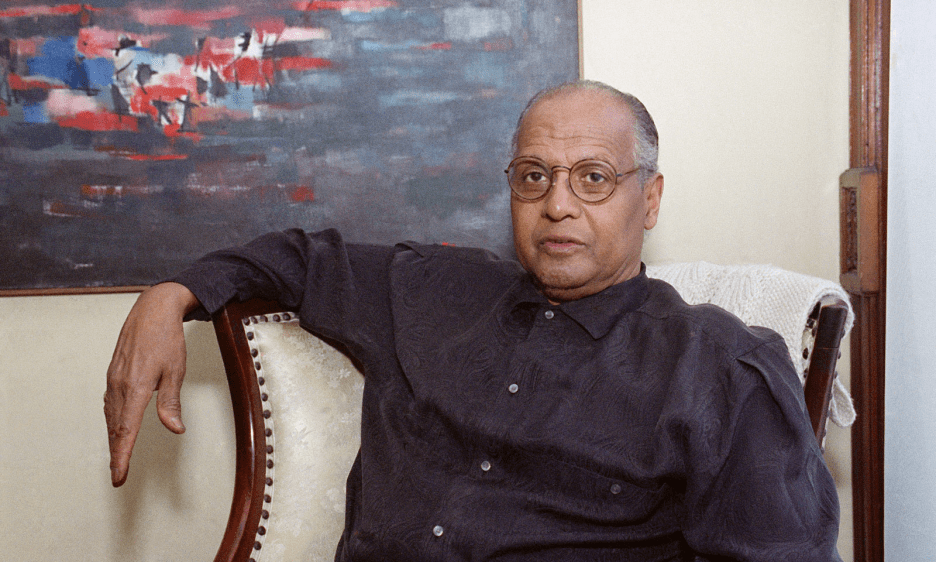

Photo of Roy DeCarava: Martin Cabrera

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.