Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Panagiotis Andreou: The World In A Bass

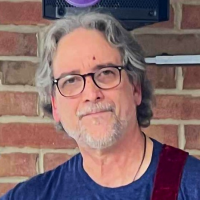

Panagiotis Andreou: The World In A Bass

In order for me to jam with and be comfortable with all of the great musicians I have known, my ‘passport’ to that has always been to be myself.

—Panagiotis Andreou

When they started playing off-the-cuff in changeable pairs, magic started to flow and smiles spread around the bobbing heads in the crowd. When it came time for Andreou's turn though, there almost an audible "snap" at the number of heads spun around by the sounds he produced. If you asked him, Andreou would likely say, "Oh, that's just me doing my schtick," but few there had heard anything quite like it before. Beyond the obvious rhythmic and harmonic acumen (and the simultaneous layering of Konnakol over what he was playing), his lines somehow transmitted an underlying wealth of knowledge from myriad musical traditions— combined into something fierce and unique. This notion was something wholly cemented by his crushing performance with a full band later that same evening.

It's no wonder that he is the bassist of choice for forward-thinking, genre-busting groups like Now vs Now, The New York Gypsy All-Stars, Gonzalo Grau and La Clave Secreta and many others.

He doesn't consider himself a "jazz guy" despite a degree from Berklee (and a master's from the jazz program at SUNY Purchase). His undeniable Greek spirit is infectious, his technique prodigious and his humility endearing (if not amusing). He spoke with All About Jazz as he was preparing for a short run of shows with Ethiopian ethno-jazz legend Mulatu Asatke...

All About Jazz: So what's on your plate right now?

Pangiotis Andreou: I'm touring this whole week with Mulatu Asatke and we're playing Le Poisson Rouge. On piano is Jason Lindner and he's also the musical director for the band. On drums is Marcus Gilmore. I'm telling you this basically because I have today and tomorrow to learn a bunch of music. It's not difficult, it's just... I had thought I was going to be able to learn it by memory, but that's not gonna happen... laughs... So basically I'm gonna be in here playing this music all day and tomorrow the same thing. Hopefully it's gonna be ok. We have minimal rehearsal in Chicago, then we're playing Toronto and Montreal, then coming back to New York.

AAJ: Well thanks for taking a break to talk. How about beginning with your musical interests, exposures and upbringing in Greece...

PA: I was born in Athens and more or less lived there until I was 21. Athens is a big city, about 5 million people, but it still felt very conservative. Now it's much more open because the whole world is connecting, but then it seemed to me that it was very limiting and I wanted to see the world. We only had two channels. I don't want you to think it was a Communist state or anything, it was the norm everywhere. So even being in the city, I wanted to get out and see the world. That has been a driving force for me—and of course music too. Through music, thank god, I've gotten to travel to so many different places

I grew up with Greek music on my father's side. Working class music, you know? Bouzouki and all but like really good stuff. I never disliked it but in coming here, I came to appreciate how much lies within your tone in Greek music and all the unique phrasing there.

So that was my father's side. My mother was the exact opposite. She was a very modern woman for her time. Being a woman such as that in Greece, during those times was very difficult for her. She wore her mini skirts and she would listen to foreign music. When she was young she would always look for those radio shows that were playing the Beatles and rock and roll—the Animals, the Monkees, the Turtles and the Rolling Stones and all that. She was very into and exposed me to Western culture. I think she actually insisted for me to start playing so that's where the musical journey really started. So between my mother and father, it was a good balance of musical influences.

It's kind of funny, my first English words came from the Beatles. I'm still a Beatles freak. There were LPs in the house that I was playing all the time. I remember my father got me a Walkman and it was like the most amazing thing. I completely melted tapes. Destroyed tapes. I would record radio shows. I would get lost in the 60's rock stuff but also the more commercial stuff—Elvis, Motown, Neil Sedaka. You know they used to have those "collections" back in the day—two tape sets—they made it to Greece a lot. So a lot of this stuff for me was like already traveling abroad, you know?

AAJ: Do you remember the first instrument you played?.

PA: You won't believe this but I actually played baroque flute—like the recorder—both alto and bass, for ten years. I played a lot of medieval European music. I think that might have been the foundation of whatever Western harmony I still know today. Then from there I went to this Musical High School. My mom was the one that kind of pushed me.

I was lucky. My father came from a very conservative background. He ended up being a lawyer but he never pushed me to become a lawyer—that's what usually happens [in Greece]. You know how the old-school societies are, you follow in your father's profession or family business. But they never pressed me and they never told me what to do either. My mom wanted to make sure... It's because of her that I have this direction with music.

So then I went to this musical high school. I was very lucky because it's a public system in Greece where you would do the regular school during the day like everybody else, then we would stay for the rest of the day for [music] classes outside [the curriculum]. And it was public—we were not paying anything for that. You would enter by audition. Then you would get to do an extra four of five hours of music. That was very open too. I mean you would do classical and byzantine music—because that was part of our "national propaganda" (laughs)—but it was cool music actually and very interesting stuff. You know, there was kind of always a little "parenthesis" around everything though. There was always a bit of national bias behind everything you heard. That's true really everywhere in the world, but a bit magnified in Greece because we were under Ottoman rule for 400 years. It's just a very complicated thing to be Greek sometimes, very confusing. (laughs).

Anyway, I got to study Western music in that high school and took classical piano there and classical clarinet, But then I remember the day I saw somebody playing electric bass... and I just knew I had to do that.

AAJ: So what were your beginnings as a bassist?

PA: You know, the only non-Greek way to be rebellious in my teens was to play heavy metal. (laughs) So I started playing Metallica and Manowar and some Iron Maiden but that was a really quick period. I started thinking that the instrument was a lot of fun, I loved the sound and I also thought is was easy. It only had four strings and I asked the guitarist how you tune it... I guess I was kind of good at it for a teenager. I quickly began playing with older kids doing stuff like Bon Jovi and Bryan Adams. That was cool for me too, something new. I never listened to it. I mean, it was on the radio but... See, I'm 40, not 45, not 35 and it's kind of an in-between generation. I got the 80's thing but I was a kid. The '90s thing, I was a teenager...

Then really quickly, for some reason, somebody saw me and I got to play in a band that was covering Motown. Then I got exposed to Aretha Franklin and all the classic stuff, but that was also really short. I was really lucky because there was this guy, his name was Yiotis, he was my first actual bass teacher. This guy had just come from L.A., he was a fusion cat with a very great personality. He was very "non-miserable," which would be the norm....

AAJ: (laughs) What do you mean?

PA: Oh, you know, you would have guys who knew twenty-three standards and would think they were the president of the country. And everybody else sucks. (laughs) You know what I mean? This guy was not like that. Already for his generation, he was a fusion guy who studied with [Tribal Tech bassist] Gary Willis at MI [Musician's Institute], which at the time was very legendary. He came back with his 5-string Tobias, had amazing technique and was slapping—and he was a very happy guy with very positive energy and I was lucky enough to be his student. He really liked me too and thought I was good—then immediately I started playing a lot.

Also the leader of that Motown band I was playing with, he went to Cuba and came back with some Latin CDs, That was like the Cambrian explosion for me. By earth history standards we're talkin' about a HUGE era in my life beginning. My rhythmic language still comes heavily from that Afro-Cuban influence. So I got into that.

There was a scene in the '90s Athens that was pretty substantial—like five or six clubs packed, live bands every night. Good times and money was good back then. I was getting paid, playing Salsa and I was always around Greek music too and aware of all the other music around us—Bulgarian, Turkish, etc.

AAJ: So you were playing and studying all of these different types of music around you, but not necessarily from a jazz point of view yet— more from simply a "bass perspective."

PA: Well, we didn't have "bass culture" there. You didn't really approach things from a bass perspective, as perhaps a jazz player would, but from a melody perspective. A big chunk of Greek music falls under the category of the "Eastern World"—like the modal and the melodic and syllabic rhythm. I grew up with a lot of that. So bass is like this thing that they didn't know what it was—low in the mix playing downbeats. Downbeats in 9 and in 7, but still on downbeats.

When I first heard Salsa I was like, "This cannot be possible. This is pop music. Everybody listens to this." That was kind of the problem I had with the jazz guys at first because Greek people, we're kind of not really wired to listen to II-V-I's with extensions. Athens is a city of theaters, most theaters per capita. I'm a Gemini, I'm an only child, I needed to connect with people always. I was always impressed with [Greek folk music]. That's why I learned so many folk styles that seem to be complicated to Western ears. And people dig it and dance and know the songs. So I was like, "How is it possible for the bass to be that loud, for the bass never to play on the one, and for that to be allowed?" So I started with salsa, latin jazz, Tito Puente. I was a teenager in the '90s playing Tito Puente covers with a band that had timbales and congas and singers and horns... amazing and so much fun. Then the Timba fever came in the '90s. That came out and there were Cubans in Athens. They would start playing these new things, explosive shit—aggressive low-end stuff for five-string bass. My "metal" side was still there and very macho...

See, I never "studied" Latin music, I just played it. Because if you don't play it with a band, you're never going to learn it. You have to relate to a minimum of like three or four [rhythmic] patterns at any given time. You have to learn how to listen and how to lock with the congas.

AAJ: So I'm a little confused over the chronology. You started playing bass, you heard Latin music, at what point did you leave Greece?

PA: Well, at first I did go to study in Denmark when I was 18, but that didn't work out—I didn't even really end up studying there. See, in my little village in Athens I thought I was good but then when I went to Denmark, by their academic standards I was definitely not up to par. I didn't even make it through the first audition.

AAJ: So what did you do?

PA: So Jamiroquai was really big then and I ended up playing with a Jamiroquai cover band there (laughs). I was a Jamiroquai freak too. You know tunes like "Emergency On Planet Earth," "Space Cowboy..." and then I came back [to Athens] and studied with this bassist [Yiotis] I told you about.

At the same time I started playing Greek music professionally to pay to go to the conservatory. The conservatory I went to—it's called Philippos Nakas—it was affiliated with the Berklee network and they held auditions every year. I took an audition and I got some money. My parents helped me get to the States and I studied at Berklee in Boston. I graduated in three years—'99 to 2002.

Then I went to New York right away. I applied for an option for a practical training, a class for foreigners and got it. I looked for schools—I couldn't do Manhattan School of Music or The New School because I wouldn't be able to afford it. I looked at SUNY and Patterson and CUNY and ended up going to SUNY Purchase which is like a bebop capital, you know. I probably was the last electric player they ever accepted. (laughs). I learned a lot and I had some great teachers too, but I don't think they even really wanted me there. (laughs). I wasn't playing upright, you know. I had Dennis Irwin as a teacher though so that was amazing. He was a great guy, very positive.

I'm teaching a little more now and I'm realizing that all of these "positive" teachers that had a huge impact on me, they were all like, "Have fun with it," you know?

Then I graduated and started playing immediately. I was playing with Pedrito Martinez a lot. I was playing at Guantanamera five nights a week with him. Then he hooked me up with this band called Yerba Buena and I toured with them for two years. They were fairly well known and played really big festivals. Then I was just playing a lot and that's when I first met [keyboardist] Jason [Lindner].

AAJ: Did you play with Gonzalo Grau and La Clave Secreta before you played with Jason Lindner?

PA: That was in Berklee, yes. Being at Berklee my first teacher was Oscar Stagnaro, the bassist for Paquito D'Rivera. I already went there on a mission to get all the Latin stuff immediately. Again, [before that] I didn't really study it but I was around it a lot so right away I was doing the Latin Jazz Jam at Wally's—I don't know if you know the place—like the Smalls of Boston. There was like this rumor about me I guess—this Greek guy who plays Timba, you know. Then I started playing with Francisco Mela and Danilo Pérez got to hear me and said that he liked my playing. So I was deep in the Latin thing there and I met Gonzalo Grau. Then I got to play with him. And playing with a 12-piece band with horns, percussion and singers and everything was like amazing—it was such a great sound. Then we had this record in 2009 (Frutero Moderno) that made it to the Grammys. It was like a two thousand-dollar recording and we're competing with BMG and Sony in the category. Of course we didn't win but it was amazing for me to make it all the way there. We're still playing and we just recorded an album that's going to be coming out little by little. We don't know what to do with it nowadays, you know but the music is incredible. Gonzalo is a brother. He and Jason are like my mentors in some ways but also close friends.

So it was after that I met Jason—and that's another huge chapter in my life. I made it a point to try and meet him because I knew of Jason from (bassist) Avishai Cohen's records—a couple of which I played A LOT in Berklee. I knew he was arranging stuff and I loved his playing and vibe—very unique. Jason got to see me with this legendary Turkish clarinetist, Husnu Senlendirici and afterwards we met. The next thing you know it's like "Let's make a band." I guess the first time was with Dafnis Prieto on drums, then Daniel Freedman, then the third gig was Mark Guiliana and that was it, that was the trio (Now vs. Now). So that was the line-up for like eight years I guess. We did two records, the first produced by MeShell NdegeOcello. That was huge because we were like a jam band but through her influence, we actually became a band—with songs that had a beginning, middle and end.

AAJ: So Now vs Now was initially doing more freeform, improv stuff?

PA: Which was necessary. We did it for a good amount of time and learned so much doing that—building, creating a sound. Jason was going through this huge transitional period from playing [piano] to playing synths, going from the traditional thing to the modern thing. And Mark, I played with the guy so much and then got to see him just [imitates rocket launch with hand], I was so lucky. In general, if I could "sell" anything with my bio, it would be the list of drummers that I've been lucky to have played with. In my head at least. I know drums and I've played with so many great drummers—Jojo Mayer, Justin Brown, Zach Danziger, Nate Wood, and now Justin Tyson. All the cuban monsters—I got my ass kicked by them all, it was great.

AAJ: So somewhere during Now vs Now, you also hooked up with the NY Gypsy All-Stars, correct?

PA: Parallel to that. I met [clarinetist] Ismail [Lumanovski] right after my Master's degree around 2004. He was 19, I was like 24. Because of Husnu.... that band was kind of like the first to unify the whole region's music. It wasn't just Turkish or Greek music, it was everybody from the region. And I really loved the way they played. They were fusion guys jamming like crazy in odd meters and everything and I was like "Oh wow, you can do it," you know? I think Ismail was really influenced by that too.

I also got to check the Balkan thing when I got to play with legendary Bulgarian accordionist, Ivan Milev. It is a school of its own with really fast, odd meters and busy melodies and all that. The bebop of the Balkans, I guess I call it. I did a record with him called The Flight of Krali Marko. It's on spotify.

Anyway, I had that and the Latin thing—plus the Greek thing I already had. Prior to that I would play all these weddings and I ended up singing too. I used to play the old-school New York thing where 4:00 am they would close the door and we would play continuously till 6:00—and throw money and plates. The drummer from the Gypsy All-Stars— Engin [Kaan Gunaydin] played in these so much with me and he hooked me up with all these Turkish gigs as well so I got to do that too. So all of this and then the story of how we met is on our Facebook page under Biography. [For the story, click here]

So the owner of Drom—where we played all of the time—decided we should be a band. We started as a trio. Then Tamer Pinarbasi, the Kanun player came, who's like a beast on the instrument and a legend in the Near East and the Middle Eastern world. Then the drummer came and that was it, that's the core of the band. Only keyboard players have changed—which I've been responsible for. We had Axel Tosca Laugart, Pablo Vergara, Manu Koch, now Marius van den Brink—Jason was there for quite some time. Jason also produced the second album (Dromomania— independent, 2014), which is the more Western thing that we did. I still work a lot with the guys, we play a lot. This whole Summer is basically touring with them.

Our [NYGAS] music is the Balkans, which is another big chapter for me because I've been playing it for 15 years, it's very challenging stuff. It's some of the most fiery European music you'll find at the folk level. The mechanism that I learned from the Afro-Cuban and Afro-Latino stuff, I kind of used it there. That's my little schtick, you know... it's like a Cuban/Balkan thing. (laughs)

AAJ: I saw that the All-Stars got to play with an orchestra recently.

PA: That's a new project that we made new arrangements for, it's incredible. We just played in the Musikverein in Vienna which is like the Carnegie Hall of Europe. Mozart played there, Beethoven played there and I was playing there with my electric 5-string. (laughs) A classical piano playing friend of mine said I was probably Greek number five that played there in the history of the place. (laughs)

You know what the funniest thing is? I've played the biggest Jazz festivals in the world, right? I know 13 standards... I can name them for you... (laughs) I mean it's incredible and this is because of Now vs Now. It's amazing the lessons that I've learned from that: Be yourself, be honest, have confidence. There's no limit. Ok, I'm probably not going to end up playing with Chick Corea but...

AAJ: You could...

PA: (laughs) I don't know, maybe...

AAJ: It's interesting to look at your two main projects side by side. The NY Gypsy All-Stars have the ethnic thing in the foreground supported by a platform that includes, well everything—Jazz, modern, electronic, fusion. Now vs Now is reversed in a way where it's a powerful but amorphous mix of Jazz, Electronica, Modern stuff on the surface but listening, you can hear the ethnic influences you bring to the table—the odd meter, the Greek, the Indian, and funk and Latin as well...

PA: I never thought of it like that and I think you might be right in a way. One is an Eastern thing with a contemporary Western thing as support. Now vs Now is the Western thing with a tone of who I am.

AAJ: Not even mentioning the outright Konnakol you sometimes do in Now vs Now, you can hear in a tune like say, "Ancient Alien" from Earth Analog (self-released 2013) that the challenging rhythmic framework might be aided and informed by Konnakol's rhythmic dissection. Is that on point?

PA: The Konnakol thing... if you see in the early Youtube videos, I'm like mumbling stuff. (pause) Look being Greek, we belong to the Eastern world rhythmically, no doubt, Syllabic, melodic, modal music—like it's the same grand frame. Then I got this amazing opportunity through Prasanna—guitarist, Indian guy whom I played with a lot. Manu Koch, the keyboard player from Switzerland who also played with the All-Stars, he went there [India] to teach. He came back excited and said, "Man they opened this school and Prasanna has open curriculum. It's in the countryside and they are looking for teachers." I said, "I'm in, let's do it." So I got a gig teaching and my own apartment in this special economic zone that was basically empty. The only school that was open was this music academy there. I got to teach and I became really good friends with the great classical Indian percussionist and ghatam player—Ghatam Karthick. This was in the south, where konnakol comes from. So I went there and I'm like, "Oh shit, there's a system, you're kidding me... You can do that legitimately now" (laughs) The first time in 2011 Jason was with me and then I went back again to teach the following year. Incredible experience spending two and a half months each time in India. It's a different planet...

AAJ: So with your Greek upbringing, your mania for Latin music and your knowledge of Indian Konnakol, you bring a unique set of influences to bear upon the music. Do you see any parallels between them?

PA: You know, my goal—and I know a lot of musicians who have a similar goal—is to try and unify... to find that spot where all these influences meet. I'm a Darwinist fanatic and evolution just takes time. (laughs) You blend out of necessity. There is no such thing as pure anything. Even what we consider pure was something else before.

AAJ: Have you run into many purists who would poo-poo your efforts?

PA: Everywhere. (laughs) There are "nazis" everywhere. There's Jazz Nazis, there's Indian music Nazis, there's Greek music Nazis, there's Turkish music Nazis.... (imitating) "No the comma's not there. That's not how you play this..." And then in our part of the world, thank god, there's the Gypsy thing which just cancels it. The most popular musicians that people listen to [there] are Gypsys. That's like the "Motown" of the region there and they defy rules—they bend everything to their liking—and it sounds great.

Maybe that's a bad thing and a good thing at the same time but I guess I always have to do things my own way. There was no one curriculum that I could ever follow. There's negatives in that but there's also positives because you get to take chances and to create things.

AAJ: I don't know how it was when you were a student at Berklee but now there's things like the Middle Eastern Ensemble and the Indian Ensemble that blur many lines. Did they have that when you were there?

PA: There was but it was just kind of starting you know. It was not at a high level. But look, I'm telling you just so you know, Konnakol is going to be mandatory rhythmic curriculum within the next ten to fifteen years because it's so good.

AAJ: At Berklee you mean?

PA: Anywhere. I mean there's not going to be universities anymore, it's all going to be online. It's already working like that. I have a Skype student tomorrow. He's not going to go to school. He wants to learn Latin from me and he wants THAT specific approach that I have. That happens with everybody now.

But I can tell you also that, just from being exposed so much to the Afro/Cuban thing, that the Indian thing is only half of the truth. The other half is the African thing— that I got to taste through Afro/Cuban music. In there you get that [rhythmic] byproduct of the combinations of two numbers at the same time—2 with 3, and 3 with 4—you don't get that with Indian music at the basic level.

AAJ: Is this what you mean by the term you've used in the past, "harmonic rhythm?"

PA: Yes, that's how I understand it. If you listen, the core of Afro/Cuban music is like Bata—the Nigerian thing. There's like three drums, each one has two sounds. These six sounds mix together and they all have to be aligned in a way. The Indian thing is one path, they call it "gathi" but you end up going everywhere in the universe, but through one path.

AAJ: Like the rhythmic counterpart to "Raga?"

PA: Rhythmically, the same thing. There's like rhythmic modes in a way. Their [Indian] numbers are: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. They say those are all the numbers you need to know. In the West it's like "whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note..." It's all a "four" thing. Neither of them is "right."

Listen, if I locked you in a room and told you, "This is the only tool you have to reach thirteen billion light years from here," eventually you're going to make it. There's no wrong or right.

AAJ: You also had a recent project called "Morning Bound" that was interesting. Tell a little about that...

PA: Most of the credit for that goes to the vocalist Tammy Scheffer. She's incredible. I've never met somebody who was so academically trained that would take so many chances. She would be very proper about things like posture and breathing and then she would go for the most "out" thing possible— she would be looking for it. That was amazing.

So the idea was drums, bass and voice and it put me in the position of playing chords and trying some effects. It helped me as a step to see what I can do. I wish I had the mentality then to take more advantage of it but I think for as long as it lasted, it was amazing. It was three years of experimentation... But you know how it is, you end up doing so many things. I have reached the point where I don't think I can commit to build projects like I've done with Now vs Now and the Gypsy All-Stars and Gonzalo's stuff. Now I'm just out playing again with everybody to see how it feels and learn some new things. I need to start learning new things again and I am, I'm trying.

AAJ: So with all of the arsenal you have—enviable bass technique and a wonderfully diverse set of ethnic influences—you bring to the table something unique. Any thoughts on a project as a leader?

PA: Oh yeah, that's my biggest challenge in life right now. You know to mash it together and do it and not be afraid—and to not think that it has to be perfect. Jojo [Mayer] told me that years ago, "Don't worry, just go do it. If it sucks, it sucks. You're gonna learn and expand" I guess I'm still afraid of what people are going to say— unfortunately I'm 40 and I'm still thinking of that.

It's also that I'm a bassist, I like playing bass. I like putting my lines within an idea. I like kind of a more old school approach—maybe like more of a rock approach, create a sound and everything. That's why I want to learn more and learn what I need to do.

AAJ: Well I can tell you this. While covering the GroundUp Music Festival, I attended the Bass Conversation Workshop—with you and bassists Michael League, Richard Bona, Wes Stephenson and Mono Neon. The amount of bass talent and musicality on display was obviously just ridiculous. People were digging everyone's playing and the whole pairing off thing, round-robin style. It seemed as if just when they had heard it all, the next guy would have something unique to say. But for as much as all of the others drew raves from the crowd, what you did spun A LOT of heads around. The melding of all of your influences really came through and conveyed a unique, even startling identity—in what may have been a slightly intimidating, bass-only context.

PA: Well thank you. That's my little defense, and I guess I can be negative or positive about it. I do always try to avoid the mainstream. But you know, when I grew up it was "Look at where you are. Be proud of your 'hood, your street." That's who you are and that's how people want to know about you. In order for me to jam with and be comfortable with all of the great musicians I have known, my "passport" to that has always been to be myself.

At the same time, I'm still taking so much inspiration from so many things. I'm still kind of copying away, but I can never copy. You may not know it but if anyone knows a little of rumba and rumba phrasing, it's phew... I mean I do it over eleven, okay but the concept is that I'm playing a Cuban bass line over a very fast eleven...

AAJ: You see that but if you think of most of the greats in the world, they too are at least somewhat amalgamations of different things— that you can trace back—but they have made it their own in such a way that you say, "Oh, that's them."

PA: Right and I don't think that's going to change. I mean now I'm actually really practicing again, getting in the shed and jamming over standards just to get on my fingerboard harmony thing and mechanics and stuff but I'm never gonna be somebody else. I was just playing with [drummer] Ari Hoenig in a piano trio and Ari is a super jazz player. I was like [to self], "I don't care, I'll hang, I'll find my way" and it worked out, it was fine. I'm never gonna stop being me. It would be a waste of time.

My schtick is repetitive but I've been influenced by Jason Lindner and [trumpeter] Avishai Cohen. Their thing is if you are somewhere where you are comfortable, get out of there.

AAJ: Speaking of Jason Lindner, you have a recent recording out with Now vs Now...

PA: The Buffering Cocoon... very conceptual. It was a very unique process that I've never done before. I think this is a transitional album for us and I think it's an album for listeners of what art will become in our day. Songs are going to be two minutes long because that's the attention span that people have. I'm not saying that in a negative way it's just... when you're checking out a gazillion things all the time, it makes sense.

When we went to the studio, in reality there were like two and a half songs ready. The rest was a jam that was edited by this incredible producer / musician that works with Mark [Guiliana] a lot too. His name is Steve Wall and he's like a painter. He took what we did and... it was the first time I got exposed to sonic processing, on something that I played, to that extent. That has gotten me into getting sounds and gear and pedals. I had been getting into it but now I'm more conscious of what I'm looking for. Inevitably in the future it's gonna be part of what I do just because I realize that that is the "new Western frontier."

Tags

Interviews

Panagiotis Andreou

Mike Jacobs

Richard Bona

Michael League

Dwayne "Mono Neon" Thomas

Wes Stephenson

Mulatu Asatke

Jason Lindner

Gary Willis

Jamiroquai

Pedrito Martinez

Gonzalo Grau

Oscar Stagnaro

Paquito D'Rivera

Francisco Mela

Danilo Perez

Avishai Cohen

Hüsnü Şenlendirici

Dafnis Prieto

Daniel Freedman

Mark Guiliana

Now vs Now

Meshell N'Degeocello

Jojo Mayer

Justin Brown

Zach Danziger

Nate Wood

Justin Tyson

NY Gypsy All-Stars

Ivan Milev

Tamer Pinarbasi

Axel Tosca

Pablo Vergara

Manu Koch

Marius Van den Brink

Prasanna

Kneebody

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.