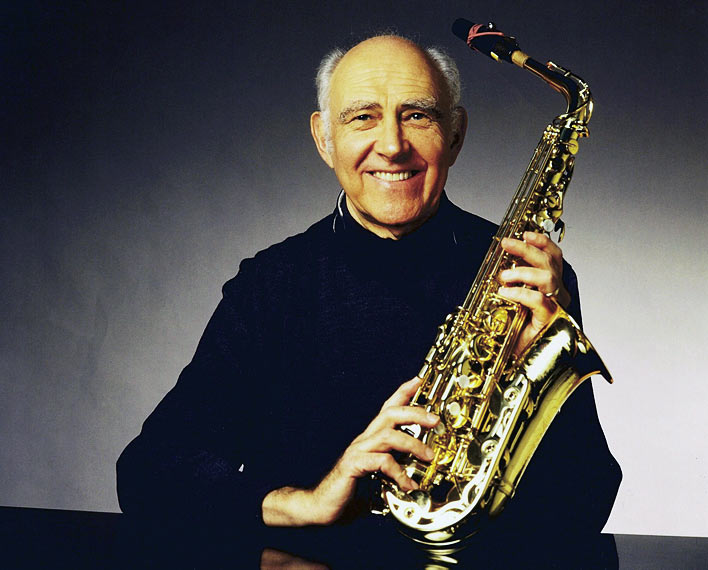

In Part 1 of my five-part interview with Herb from his home in Germany, the 81-year-old alto saxophonist talks about growing up in Los Angeles, his best friend in high school, the concert that changed his view of the alto saxophone, and what Stan Getz taught him in 1947 about the new Lester Young sound:

JazzWax: Where did you grow up?

Herb Geller: I was born in Los Angeles in 1928. My father was a tailor and ran a clothes cleaning store. He came to the U.S. from Russia in 1910 and lived in several American cities before settling in L.A. There, he met my mother at a Jewish singles dance. After they married, my parents moved from one of the poorest sections of the city to West Central Los Angeles. It was just me and my sister Betty, who is eight years older than me and today lives in Colorado.

JW: Was the Depression hard on your family in the 1930s?

HG: No. The movie industry kept the economy going in L.A. Our neighbor was a carpenter at 20th Century Fox, and everyone seemed connected to the film business in some way. My mother played piano in a theater that showed silent films.

JW: When did your interest in music start?

HG: My father and mother socialized weekly with the same group of Jewish immigrants who were striving to make it into the middle class. Every Saturday they'd get together to play cards. The men played poker and the women played mahjong. Max Flack, one of the card players, owned a small music store, and he sold records and every instrument imaginable. He also gave lessons. His wife taught violin and piano. They said to my father during one of those card games, “Herb should get a music education."

JW: Did your parents agree?

HG: Yes. Max said it was very important that I learned to read and write music. My father said, “Great, he should learn the violin." Max objected, saying the violin was too old-fashioned and that in the modern world, the saxophone and clarinet were the exciting instruments. “Like Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw--nice Jewish boys, not music of the shtetl," he said.

JW: What did your father say?

HG: My father agreed, and Max sold him a used alto saxophone. Once a week Max came over to our house and gave me lessons for $1.

JW: How old were you?

HG: I began playing the alto saxophone at age 8. I was always advanced, probably because I had started school a year early, at age 4. My mother and father had lied about my age and said I was 5. They were both working, and getting me into school early let them get on with their lives. By the time I reached junior high school, I was playing the alto saxophone and clarinet. Max Flack was a very good teacher.

JW: Were you also listening to records?

HG: Yes. My first favorite 78-rpm disc was Glenn Miller's Serenade in Blue. I learned the song on the saxophone by ear. By the time I reached high school, I was in a swing band. The school--Susan Miller Dorsey High School [pictured]--was completely integrated with blacks and whites and some Asian kids as well. So what you looked like made no difference to any of us, especially if you were studying music.

JW: Who was your closest friend in high school?

HG: Eric Dolphy [pictured]. Eric and I thought we were the greatest saxophonists, but a girl in our band, Vi Redd, played better than both of us [laughs]. Eric and I were in the marching band together. The band marched during half time at football games. I played the clarinet and Eric played the oboe.

JW: Did Dolphy like the instrument?

HG: Nobody likes playing the oboe [laughs].

JW: As what point did you turn to jazz?

HG: In 1944, when I was 15 years old, a bunch of us from the high school band went to the Orpheum Theater in L.A. to see Benny Carter's [pictured] orchestra, the Nat Cole Trio and a film. I couldn't believe it. I went back to see the show two or three times on Saturday and Sunday. So did Eric, Vi and everyone else. Max Roach was playing drums in Benny's band and J.J. Johnson was on trombone. I was enthralled. It was at that moment that I said to myself, “That's what I want to do, play like Benny Carter."

JW: Why?

HG: Benny could play the alto fluidly, then pick up the trumpet and play a fantastic solo on I Surrender Dear. Then he'd tell jokes. He was a class entertainer. I left Glenn Miller's records behind and began to absorb all of Benny Carter's music. I also listened to Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman. Then I focused on Johnny Hodges [pictured]. I bought all of their records.

JW: When did you first hear bebop?

HG: In February 1945 I went to hear Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie at Billy Berg's club in L.A. I say 'hear' because I didn't see them. I wasn't 21 years old yet, so I had to stand outside and listen. Hearing him play was a whole new language and dialogue for me. I started listening like crazy to his records to figure out what he was doing.

JW: What was your first big paying job as a musician?

HG: During a two-week high school break I was asked to join Joe Venuti's band in San Diego in 1944. He needed a tenor saxophone, so I played the instrument in his band. My parents let me go, and it was a thrill. What a fantastic musician Venuti [pictured] was. To practice the tenor, I went to the biggest music store in town and bought Bud Freeman's Secrets of Improvisation practice book.

JW: Most of the older musicians were overseas fighting in the war, yes?

HG: Yes. I was the youngest musician in the band. Venuti's band played a show with dancers and jugglers. After Venuti, I played locally with trombonist Mike Riley at his club in Los Angeles called Mike Riley's Madhouse. Riley co-wrote the big 1930s hit The Music Goes Round and Round. He played Dixieland and needed a clarinetist. I didn't know how to play the instrument then but I gave it a shot and did alright.

JW: What did you do after high school in 1946?

HG: I started going to Los Angeles City College. I had offers from bands to go on the road. But my mother said, “No, we don't want you to become a professional musician. We want you to be an engineer or a lawyer." So I went to college. There was an orchestra at L.A. City College that recorded at a studio every school day.

JW: When did you join the musicians' union in Los Angeles?

HG: In 1944, when I was 16. That's when started to meet other bebop enthusiasts. One was pianist Russ Freeman. When I met Russ in 1947, he had just played with Charlie Parker. He told me about pianist Joe Albany, who he said was like Parker but on piano. Unfortunately Albany was institutionalized at the time for depression, so he wasn't on the scene. Art Tatum and Charlie Parker were his inspirations, Russ told me. So I started buying Albany's records. I loved to listen to the 1946 record of Joe playing She's Funny That Way with Lester Young. [Pictured: Joe Albany and his wife in 1960]

JW: Did you get to meet Albany?

HG: Yes. One afternoon in 1947 I met Joe after he was released from the hospital and convinced him to come over to my parents' place. They had sold their house and moved into an apartment by then. Joe and I played Lullaby of Rhythm for about an hour. That was a great learning experience for me.

JW: What else were you doing musically in your spare time?

HG: When pianist and arranger Dick Pierce started a big band in 1947 playing weekends, I joined on tenor sax. Then Stan Getz came to town. He had just left Benny Goodman's band, and Dick hired him for the first tenor chair. I moved over to second chair. Stan wanted to put in his union card in Los Angeles, which meant he had to sit around for six months before the local union would let him become a member. He could take some club dates but couldn't work and get paid union scale during that period.

JW: Did you become friendly with Getz?

HG: I went to visit Stan in West Hollywood for three hours of lessons. Stan asked me, “Who's your favorite tenor saxophonist?" I said, “I listen to Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster and Don Byas." Stan said, “OK, wrong. Lester Young is the guy. This is how he sounds." And then he played for me, sounding like Lester [pictured]. I had heard Lester, but I hadn't been enthralled.

JW: And after Getz played for you?

HG: I realized then that Lester was about horizontal not vertical playing. Coleman Hawkins is the perfect example of playing vertically--up and down the chords in a song. Lester, by contrast, was a horizontal player, meaning he was more focused on stressing accents and important notes in the chord but not trying to play them all. For a horizontal player, it's about the melody, the harmony line and rhythmic feeling.

JW: How else did Young's sound differ?

HG: He didn't play a big sound the way Hawkins, Webster and Byas did. They had a huge sound. I had been trying to duplicate that on the tenor. Young had a lighter sound, played with a medium reed. It was a whole different approach to the instrument. During this period, Stan was at Pontrelli's with Herbie Steward, Jimmy Giuffre and Zoot Sims playing Gene Roland's arrangements. The charts were arranged based on Lester's approach and became the basis of the Four Brothers sound that they brought into Woody Herman's band.

JW: Did you ever want to switch to tenor saxophone?

HG: No. I always wanted to be an alto player but I played tenor when jobs came up that required me to. Parker was so amazing on alto that he was actually discouraging. So I began playing the alto with Benny Carter's [pictured] sound and with Lester's horizontal feel.

Tomorrow, Herb talks about buying a hot alto saxophone from a thief, touring with Jack Fina's band, meeting his first wife Lorraine, why he moved to New York in 1949, joining the bands of Claude Thornhill and Jerry Wald, and recording with Tony Fruscella.

JazzWax tracks: Benny Carter's influential band of 1944 featuring Max Roach on drums and J.J. Johnson on trombone can be heard on Benny Carter: The Complete Capitol Sessions 1943-1946. The tracks from 1944 are Nos. 5 through 8. The CD is available here.

Tracks featuring Joe Albany with Lester Young can be found on Lester Young: The Complete Aladdin Sessions here or at iTunes.

JazzWax clip: Here's Herb with Bill Evans in 1972 in Germany. Dig the Benny Carter influence...

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.