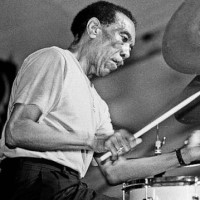

Earl Palmer was the New Orleans drummer who largely defined the beat of rock 'n roll on thousands of recordings from the late 1940s on. Dapper and outspoken, Earl Palmer may well have been the most recorded drummer in the history of popular music. He stamped his sound on everything from early Fats Domino and Little Richard hits to classic movie soundtracks to music for "The Flintstones" cartoon. Palmer recorded with Frank Sinatra, Bobby Darin, Sam Cooke, Glen Campbell, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, Ray Charles, Nat King Cole, the Everly Brothers, the Beach Boys, Willie Nelson, Sonny & Cher, the Supremes and the Monkees, among many others. He was the drummer on Ike and Tina Turner's "River Deep Mountain High," the Righteous Brothers' smash "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" and Ritchie Valens' signature "La Bamba." "He's the trunk of the tree of drumming, if not a big ol' root," said renowned New Orleans jazz, funk and rhythm & blues drummer Johnny Vidacovich. "He's part of the basic foundation. He's something we all built on." Earl Palmer grew up in the Treme neighborhood. He entered show business as a young boy, working as a tap dancer with his mother and aunt on the black vaudeville circuit. After a stint in the army during World War II, he returned to New Orleans and studied drumming. He joined the popular big band fronted by Bartholomew, a trumpeter and a friend since childhood. When Bartholomew became a talent scout and record producer for Imperial Records, he recruited Palmer as the drummer for recording sessions at sound engineer Cosimo Matassa's J&M Music Shop on North Rampart Street. Those sessions bore witness to the very dawn of rock 'n roll. Palmer's distinct back beat, built on a heavy bass kick and New Orleans second line shuffle, was also informed by bebop jazz. He considered himself a jazz musician at heart, even though his style, a synthesis of power and subtlety, facilitated popular music's transition from rhythm & blues to rock 'n roll. "Earl had a melodic sense of the bass line," Matassa said. "He didn't just do the rhythm -- he played the bottom end of the tune. It fit hand in glove with what was going on. He used his knowledge and craft, his understanding of what drums could do." Palmer provided the pulse on scores of Fats Domino singles, including his 1949 debut "The Fat Man" and his hits "I'm In Love Again," "I'm Walkin" and "My Blue Heaven." He backed Little Richard on "Long Tall Sally" and "Tutti Frutti," Smiley Lewis on "I Hear You Knocking," Lloyd Price on "Lawdy Miss Clawdy" and Shirley & Lee on "Let the Good Times Roll." "Earl was a complete musician, a complete drummer," Bartholomew said.

Read more

"In the studio, I didn't have to tell him (anything). He would tell me. If it was a sweet song, he knew how to approach it. If it was rock 'n roll, he knew how to approach that." Matassa confirms Palmer's essential role in the earliest rock 'n roll recordings. "He was a fabulous drummer, a great sideman, and he had a great attitude," Matassa said. "He was proactive. He didn't just sit there like a bump on a log. He'd ask, 'What about this? What about that?' "If you don't listen beyond what is going on with the vocalist, you miss the nuances in the records," Matassa said. "He would do things that were special, an extra roll or break. He didn't miss an opportunity to make something better." Palmer frequented the Dew Drop Inn and other fabled nightclubs. "Backbeat: Earl Palmer's Story," Tony Scherman's 1999 oral history-style biography, is rich with colorful tales of New Orleans nightlife and Mr. Palmer's adventures, romantic and otherwise. But professional ambitions, coupled with frustration over Jim Crow laws in his hometown, compelled him to move to Los Angeles in 1957. "He brought his big beat to the world," Bartholomew said. "I lost my right arm when he went to California." On the West Coast, his career as an elite, in-demand and versatile session drummer intensified. "Leaving New Orleans," Mr. Palmer said in "Backbeat," "was the best thing I ever did." A partial list of his diverse 1960s credits includes Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, Paul Anka, Mel Torme, the Ronettes, Jan & Dean, Lou Rawls, James Brown, Screamin' Jay Hawkins, Marvin Gaye, Sarah Vaughan and Neil Young. He worked with producer Phil Spector. In the 1970s he appeared on albums by Randy Newman, Bonnie Raitt, Tom Waits, Maria Muldaur, Little Feat and Teena Marie. While traveling to Los Angeles in the late 1950s, Matassa dropped in on Palmer. That day, the drummer was booked at three different studios, including the famed Capitol Records studio. An assistant leap-frogged two drum kits to the three recording sessions, dismantling the kit from the first session and setting it up for the third while Palmer worked on the second. That way, Palmer saved time by only transporting his cymbals and drum sticks from one studio to the next. His busy schedule encompassed sessions for dozens of film soundtracks during the 1960s and 1970s. They include "It's A Mad Mad Mad Mad World," "Cool Hand Luke," "In the Heat of the Night," "Valley of the Dolls," "Rosemary's Baby," "Kelly's Heroes," "Harold and Maude," "Lady Sings the Blues," "What's Up, Doc?," "Walking Tall," "The Longest Yard" and "The Rose." In the 1980s, he contributed to the soundtracks of "Gremlins," "Top Gun," "Predator," "Cocktail" and "The Fabulous Baker Boys." He played the theme song or incidental music for such television shows as "I Dream of Jeannie," "Green Acres," "Ironside," "The Brady Bunch," "The Partridge Family," "The Odd Couple" and "M.A.S.H." Unlike most musicians, Palmer was not required to attend rehearsals for film scores. "They knew that no matter what they put in front of him, no matter what oddball thing, he could cut it," Matassa said. Directly and indirectly, Palmer influenced countless drummers. John Bonham's thunderous prelude to Led Zeppelin's 1971 anthem "Rock 'n Roll" is remarkably similar to Mr. Palmer's intro on Little Richard's 1957 rave-up "Keep A Knockin'." As a young boy in the 1950s, Vidavocich listened to Palmer's recordings on 45 rpm records. That sound filtered into Vidacovich's own playing with the likes of New Orleans rhythm & blues pianist Professor Longhair, local modern jazz ensemble Astral Project and contemporary jazz pianist Joe Sample. Vidacovich befriended Palmer in the 1980s, and remained a fervent admirer of his playing and professionalism. "He did the job," Vidacovich said. "He played the music, as opposed to his agenda. He was a musician, not just a drummer. He could play any music, and had a great touch. He played between the cracks. It is straight, but it swings." Palmer continued to record through the 1990s, even as drummers ranging from the Rolling Stones' Charlie Watts to the E Street Band's Max Weinberg acknowledged his legacy. In 2000, he was inducted into the Rock 'n Roll Hall of Fame's newly created "sideman" category. Over the past decade, he occasionally returned to New Orleans to perform at the Ponderosa Stomp and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. He was sometimes tethered to an oxygen tank as he struggled with emphysema and other ailments. In 2000, San Francisco pianist Mitch Woods organized a reunion in New Orleans of surviving alumni of Dave Bartholomew's legendary 1950s studio band, including Earl Palmer. They recorded an album, "Big Easy Boogie." "I haven't played this kind of stuff in 45 years or so," Palmer said at the time. "I was getting tired - I'm a lot older now. But you don't ever forget how to do it. It's physical music, of course, but it wasn't that much of a problem. I kept telling the guys, 'There's only one more take in the old man.' "This wasn't complicated at all, as it shouldn't be," Palmer continued. "You don't want to complicate this kind of music. That's what made it last so long." New Orleans drumming legend Earl Palmer passed on Sept. 19, 2008, in Los Angeles.

Source: Keith Spera

Show less