Home » Jazz Articles » Multiple Reviews » Miles Davis: 1986-1991 The Warner Years

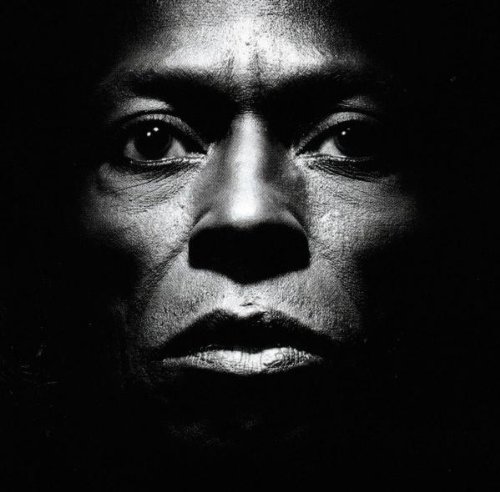

Miles Davis: 1986-1991 The Warner Years

1986-1991 The Warner Years

Warner Music France

2011

Warner Bros. was trumpeter Miles Davis's last record company, and the five years covered by the five-disc collection entitled 1986-1991 The Warner Years, pale in comparison to the 30-year, 70-disc box set of Davis' complete recordings for Columbia Records, released in 2009. So the quantity is far lower: how does the quality compare?

Davis' detractors typically divide his output into the early, good years and the late, bad years: at some point, they say, Davis simply went too far. They only disagree about when exactly Davis crossed his musical Rubicon. Some say the decisive moment occurred when the trumpeter embraced electronic instruments in 1968. Others say no, the 1970s electric Davis was fine, but his music after his return from a six-year hiatus in 1981 never reached the levels attained before his retirement. Still others like his early-1980s material, but specifically single out the late-1980s Warner Bros material as aesthetically lightweight compared with what came before. For example, Davis' superb discographer Peter Losin summarily dismisses the 1980s output, and AAJ Senior Editor Chris May makes a vigorous case that the work for Warner is inconsequential and pedestrian.

The point is that everyone who subscribes to this before-and-after theory of Davis' fall from grace will consign the Warner Brothers material, coming as it does at the end of his musical life, to the "bad" pile.

There's another narrative that people tell about Davis' long career, however. To hear them tell it, Davis spent nearly five decades continuously seeking innovation and revolutionary artistic change. There are many high points along the way, they say: Birth of the Cool (Capitol, 1949-50), Walkin' (Prestige, 1954), Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959), the December 1965 Plugged Nickel live recordings, Bitches Brew (Columbia, 1969)... But the trumpet player from St. Louis never stopped striving, and in many dimensions—his superhuman proficiency as a soloist, for example—he kept getting better and better. In this vein, the Warner recordings have their defenders: Davis' biographer Ian Carr is a passionate champion of the music, as was the late musician and critic Mike Zwerin. On this reading, Davis' last music might just be his best music.

The best or the worst Davis: which is it?

As is so often the case, the truth lies somewhere in between the two schools of thought. On balance—and unfortunately—late Davis is pretty far from the best Davis. That said, there are more than a few fine moments among the 75 tracks on this collection, and some of them are very fine indeed. And the best moments of Davis' final years suggest that he was not coasting, that his restless curiosity never faltered.

What, exactly, is included in The Warner Years? Five recordings are reproduced here in their entirety: three studio albums, including the celebrated Tutu (1986); and two vastly different live albums. Generous selections are included from two soundtracks recordings made with Marcus Miller and Michel Legrand, respectively. Finally, a full disc is devoted to a true mishmash of miscellany— guest appearances on records by artists as far-flung as Cameo, Chaka Khan, Shirley Horn, and the Italian pop singer Zucchero, as well as unreleased and barely-released recordings.

As a compilation, The Warner Years is a middling achievement. On the plus side, Ashley Kahn, (author of a fine book about the making of Kind of Blue), provides compelling liner notes, albeit in a microscopic font size. On the other hand, the collection will disappoint Davis completists, as it fails to include plenty of unreleased (or un-anthologized) nuggets in the Davis archives from these years. For enthusiasts not quite so obsessive-compulsive, this collection might nevertheless prove redundant for record libraries that already contain two or more of the albums included here—and such listeners may be less interested in Davis' minuscule guest spot with Scritti ("Wood Beez") Politti. In any case, the release provides a welcome opportunity to revisit this controversial period.

The first impression these six-plus hours of music leaves is diversity: there is no monotonous sameness here. In fact, it is unlikely that any other six-year period in Davis' career touched upon quite so many musical bases. Here he is one moment, revisiting his 1949 Nonet recordings; another, he's playing all manner of 1980s funk, live and in the studio, with ripping bands at one point and meticulously overdubbed studio wizardry the next.

The quick-and-dirty assessment: the studio albums sound remarkably strong, and make a good argument for the excellence of this period. The live albums are a disappointing mix of high and low points. The soundtracks have their moments, as does the miscellany; but the importance of these latter contributions lies not in the music itself, but in their role in establishing Davis as a sort of rock star in the latter years of his life.

The Studio Albums

Tutu, recorded in early 1986, marked a clean break with Davis' Columbia years, thanks to the innovative and fresh musical conception of bassist, multi-instrumentalist, arranger and composer Marcus Miller. Miller's presence is massive on the album: the story has it that Miller wrote and played everything, and Davis came in and soloed over the Miller tracks. That's not quite right—eight additional musicians are credited, though most for rather minor roles—but it's not too far off, either. Tutu is tight, lithe and coherent; the relentless funk is more influenced by the crisp 1980s sound of Prince than the heavier 1970s funk models that inspired Davis' earlier electric bands. Tutu stands as the first and best moment in Davis' Warner years, and arguably one of his finest moments ever. It's the only music here that is not only of its time—rarely has any Davis music sounded quite so obsessed with contemporaneity—but in fact helped define the musical sound of its time. ("The best jazz record of the decade is Tutu by Miles Davis. Absolutely no doubt about it," according to Mike Zwerin. "It is the soundtrack to the movie of our lives.")

Tutu, recorded in early 1986, marked a clean break with Davis' Columbia years, thanks to the innovative and fresh musical conception of bassist, multi-instrumentalist, arranger and composer Marcus Miller. Miller's presence is massive on the album: the story has it that Miller wrote and played everything, and Davis came in and soloed over the Miller tracks. That's not quite right—eight additional musicians are credited, though most for rather minor roles—but it's not too far off, either. Tutu is tight, lithe and coherent; the relentless funk is more influenced by the crisp 1980s sound of Prince than the heavier 1970s funk models that inspired Davis' earlier electric bands. Tutu stands as the first and best moment in Davis' Warner years, and arguably one of his finest moments ever. It's the only music here that is not only of its time—rarely has any Davis music sounded quite so obsessed with contemporaneity—but in fact helped define the musical sound of its time. ("The best jazz record of the decade is Tutu by Miles Davis. Absolutely no doubt about it," according to Mike Zwerin. "It is the soundtrack to the movie of our lives.") Amandla (1989) was recorded more than two years after Tutu and has aged remarkably well. It sounds as though it began as a kind of "Tutu II," with a strong bedrock of Miller compositions and production; this is heard to fine effect in the intertwining of Davis' trumpet and Miller's bass clarinet on the latter's "Hannibal," for example. But Miller's leading role was diluted by spreading the production credits across a handful of Davis associates. Moreover, Amandla sounds like a band rather than Marcus Miller studio wizardry, undergirded by the swinging drums of Ricky Wellman, then a star of the Washington, DC go-go movement.

Amandla (1989) was recorded more than two years after Tutu and has aged remarkably well. It sounds as though it began as a kind of "Tutu II," with a strong bedrock of Miller compositions and production; this is heard to fine effect in the intertwining of Davis' trumpet and Miller's bass clarinet on the latter's "Hannibal," for example. But Miller's leading role was diluted by spreading the production credits across a handful of Davis associates. Moreover, Amandla sounds like a band rather than Marcus Miller studio wizardry, undergirded by the swinging drums of Ricky Wellman, then a star of the Washington, DC go-go movement.Doo-Bop (posthumously released in 1992) is based around a collaboration with rapper/producer Easy Mo Bee that was cut short by the trumpeter's death in September 1991. Six tracks were completed, with Mo Bee playing the Marcus Miller role and Davis soloing over the hip-hop sampling. The producer filled out the record using additional Davis solo recordings. The raps on Doo-Bop—mostly fawning panegyrics to Davis—have not aged well, but Mo Bee's production and Davis' playing sound surprisingly strong. "Chocolate Chip" is a particularly effective mixture of sampling, beat and trumpet soloing.

The Live Albums

The proponents of this phase in Davis' career make their case by pointing to his marathon concerts and generous attitude toward his audience. Moreover, concerts were the only place to hear Davis' new compositions—his contract with Warner gave the record company the publishing rights to his music, and as a result Davis put none of his own tunes on the studio albums reviewed above. Late-1980s Davis in concert was Davis unfiltered by Marcus Miller or anyone else, the energetic funk-jazz he had been developing since the early 1970s transparently on display.

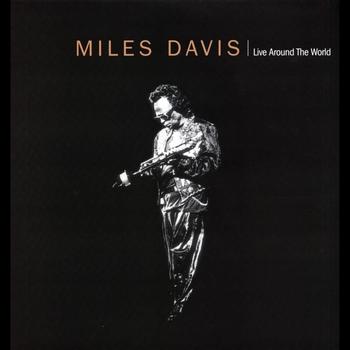

The 1988-1991 recordings gathered on Live Around The World (released in 1996) present a hard- working and entertaining band, though one that is light years from the heft of the frightening and tectonic double-live albums Davis released in the first half of the 1970s. There's a moment near the end of the band's version of "Tutu," recorded at Montreux in July 1990, when Davis realizes that the entire audience, and not only Kenny Garrett's flute, is repeating his trumpet phrases back at him, and he playfully eggs them on. In another cut, Garrett plays a raucous arpeggio of choruses to bring "Human Nature" to a tremendous climax, after which Davis' famous rasp can be heard, plainly pleased, amidst the applause: "That wasn't nothin'!" There are many better Miles Davis concerts available on record, but none with this level of warmth emanating from the erstwhile Prince of Darkness. (A better record of Davis's live work in the 1980s is provided by the massive 10-DVD collection of his concerts at the Montreux Jazz Festival over the years.)

The 1988-1991 recordings gathered on Live Around The World (released in 1996) present a hard- working and entertaining band, though one that is light years from the heft of the frightening and tectonic double-live albums Davis released in the first half of the 1970s. There's a moment near the end of the band's version of "Tutu," recorded at Montreux in July 1990, when Davis realizes that the entire audience, and not only Kenny Garrett's flute, is repeating his trumpet phrases back at him, and he playfully eggs them on. In another cut, Garrett plays a raucous arpeggio of choruses to bring "Human Nature" to a tremendous climax, after which Davis' famous rasp can be heard, plainly pleased, amidst the applause: "That wasn't nothin'!" There are many better Miles Davis concerts available on record, but none with this level of warmth emanating from the erstwhile Prince of Darkness. (A better record of Davis's live work in the 1980s is provided by the massive 10-DVD collection of his concerts at the Montreux Jazz Festival over the years.) Miles & Quincy Live At Montreux (recorded in July 1991 and released in 1993) finds Miles revisiting his historic collaborations with Gil Evans, taken from the Birth of the Cool (1949-50), Miles Ahead (1957), Porgy & Bess (1958) and Sketches of Spain (1959-60) projects. The Montreux concert has virtually nothing to do with the performances on Live Around The World. Davis had resisted playing this material again for decades, but Quincy Jones apparently raised the price to a point where the trumpeter could not refuse. In general, these late readings under Jones's baton sound lackluster in comparison to the dusting-off Vince Mendoza and Terence Blanchard gave this material at the 2011 Monterey Jazz Festival. Davis, clearly in failing health, nevertheless rouses himself for some fine solo moments on "Boplicity," "Springville" and the Porgy and Bess numbers (Ian Carr's biography provides a blow-by-blow of the performance).

Miles & Quincy Live At Montreux (recorded in July 1991 and released in 1993) finds Miles revisiting his historic collaborations with Gil Evans, taken from the Birth of the Cool (1949-50), Miles Ahead (1957), Porgy & Bess (1958) and Sketches of Spain (1959-60) projects. The Montreux concert has virtually nothing to do with the performances on Live Around The World. Davis had resisted playing this material again for decades, but Quincy Jones apparently raised the price to a point where the trumpeter could not refuse. In general, these late readings under Jones's baton sound lackluster in comparison to the dusting-off Vince Mendoza and Terence Blanchard gave this material at the 2011 Monterey Jazz Festival. Davis, clearly in failing health, nevertheless rouses himself for some fine solo moments on "Boplicity," "Springville" and the Porgy and Bess numbers (Ian Carr's biography provides a blow-by-blow of the performance).The Soundtracks

Generous selections are included from two soundtracks: Siesta (1987), made with Marcus Miller and Dingo (1990), made with Michel Legrand. On the basis of the music offered here, most are unlikely to quibble that the whole soundtrack albums have not been included. Miller's Siesta sounds dated and tired in a way that Tutu and Amandla do not. Dingo (in which Davis starred), in contrast, sounds better than expected, and includes snippets of dialogue that help reconstruct the story and add to the charm of the selections. Legrand's "Concert on the Runway" winks at Milestones (1958), and "The Dream," though slight, is a wistful and lovely melody. Neither soundtrack approaches the standard of L'ascenseur pour l'échafaud (Fontana, 1958), Davis' incandescent soundtrack to the Louis Malle film.

Generous selections are included from two soundtracks: Siesta (1987), made with Marcus Miller and Dingo (1990), made with Michel Legrand. On the basis of the music offered here, most are unlikely to quibble that the whole soundtrack albums have not been included. Miller's Siesta sounds dated and tired in a way that Tutu and Amandla do not. Dingo (in which Davis starred), in contrast, sounds better than expected, and includes snippets of dialogue that help reconstruct the story and add to the charm of the selections. Legrand's "Concert on the Runway" winks at Milestones (1958), and "The Dream," though slight, is a wistful and lovely melody. Neither soundtrack approaches the standard of L'ascenseur pour l'échafaud (Fontana, 1958), Davis' incandescent soundtrack to the Louis Malle film. One fine number—"Gloria's Story"—is excerpted, on the rarities disc, from the substantially more interesting soundtrack to The Hot Spot (BMG, 1990). This record, made with John Lee Hooker and Jack Nitzsche, could have been more generously represented, but then again it was released on another record label—and these are the Warner Years, after all.

One fine number—"Gloria's Story"—is excerpted, on the rarities disc, from the substantially more interesting soundtrack to The Hot Spot (BMG, 1990). This record, made with John Lee Hooker and Jack Nitzsche, could have been more generously represented, but then again it was released on another record label—and these are the Warner Years, after all.The Miscellany

It's amongst the odd tracks jumbled together on the fifth disc that the value-added part of this collection lies. After all, there are no bonus tracks added to the albums proper, no alternative takes. The rarities disc begins with recordings made before Tutu, the so-called "Rubberband" sessions of 1985 (two tracks are released here for the first time, while another included here was only recently released on another anthology). These are revealed to be vigorously played but rather mechanistic funk. Despite some spirited soloing from the leader and others, their interest is limited.

The bulk of the rarities are guest appearances by Davis on records by others during the period. This is another break with practice from previous decades, in which Davis' sideman credits were sparse relative to others of his generation. The Prince-produced and dominated Chaka Khan track "Sticky Wicked" or the track by Cameo are pure, thudding 1980s funk. Indeed, these selections reveal that the Rubberband sessions had actually captured more or less accurately the slick and slightly soulless funk sound that was in the air in the 1980s. Against this somewhat insipid backdrop, the fresh sound of Tutu and the swing of Amandla are cast in even starker relief.

Contributions to albums by Davis' sidemen—Marcus Miller and saxophonist Kenny Garrett, arguably the stars of this compilation—are better than average examples of the fast-funk sound Davis was seeking, but they don't sound as good as Miles's own studio albums of the period.

A lovely muted solo on long-time friend Shirley Horn's "You Won't Forget Me" is the last track, and a perfect close to the collection, though stylistically completely distinct from the other guest appearances. Chronologically speaking, the last recording made by Davis herein, is a rousing version of "Hannibal," recorded live at the Hollywood Bowl in August 1991, just days before Davis would be hospitalized with pneumonia, and about a month before he died of complications of a stroke. Davis sounds vibrant and heroic, trading phrases with Garrett. Two ways to end the story: one bittersweet and looking backward; the other resolutely facing the future.

What The Warner Years taken as a whole manages to communicate—something that no single album of the period could do on its own—is the trumpeter's unique persona in the late 1980s and early 1990s: the Global Rock Star. The strong music that pops up herein with regularity makes the case for the respect due to the Rock Star—making a link to his undisputed masterpieces of the past. But it's his promiscuous guest appearances (matched by TV cameos), his movie role in Dingo, and his crowd-pleasing concerts that complete the picture. This is a role that Davis, despite his multifaceted fame, had not played in decades past. He sounds like he's enjoying it.

Tracks and Personnel

Tracks: CD1: Tutu; Tomaas; Portia; Splatch; Backyard Ritual; Perfect Way; Don't Lose Your Mind; Full Nelson; Siesta/Kitt's Kiss/Lost In Madrid Part II; Theme For Augustine/Wind/Seduction/Kiss; Lost In Madrid Part IV/Rat Dance/The Call; Claire/Lost In Madrid Part V; Los Feliz; Catémbe; Cobra.

CD2: Big Time; Hannibal; Jo-Jo; Amandla; Jilli; Mr. Pastorius; The Arrival; Concert On The Runway; The Departure; Trumpet Cleaning; The Dream; Paris Walking II; The Jam Session; In A Silent Way; Intruder; New Blues.

CD3: Human Nature; Mr. Pastorius; Amandla; Wrinkle; Tutu; Full Nelson; Time After Time; Hannibal; Introduction By Claude Nobs And Quincy Jones; Boplicity; Introduction To Miles Ahead Medley; Springville; Maids Of Cadiz; The Duke; My Ship.

CD4: Miles Ahead; Blues For Pablo; Introduction To Porgy And Bess Medley; Orgone; Gone, Gone, Gone; Summertime; Here Comes De Honey Man; The Pan Piper; Solea; Mystery; The Doo-Bop Song; Chocolate Chip; High Speed Chase; Blow; Sonya; Fantasy; Duke Booty; Mystery.

CD5: Maze; See I See; Rubber Band; Digg That; Oh Patti (Don't Feel Sorry For Loverboy); In The Night; Sticky Wicked; I'll Be Around; Dune Mosse; Big Ol' Head; Free Mandela; Rampage; Gloria's Story; You Won't Forget Me.

Collective Personnel: Miles Davis: trumpet, keyboards; Marcus Miller: bass, synthesizer programming, bass clarinet, soprano saxophone, guitar, keyboards, drums, percussion; Benny Bailey: trumpet, flugelhorn; Oscar Brashear: trumpet; Ray Brown: trumpet; John D'earth: trumpet, flugelhorn; Miles Evans: trumpet; Chuck Findlay: trumpet; Atlanta Bliss: trumpet; George Graham: trumpet; Sal Marquez: trumpet; Wallace Roney: trumpet, flugelhorn; Manfred Schoof: trumpet, flugelhorn; Nolan Smith: trumpet; Lew Soloff: trumpet; Marvin Stamm: trumpet, flugelhorn; Ack van Royen: trumpet, flugelhorn; Jack Walrath: trumpet, flugelhorn; Dave Bargeron: euphonium, trombone; George Bohanan: trombone; Jimmy Cleveland: trombone; Roland Dahinden: trombone; Thurman Green: trombone; Conrad Herwig: trombone;Tom Malone: trombone; Lew McCreary: trombone; Earl McIntyre: euphonium, trombone; Dick Nash: trombone; Dave Taylor: bass trombone; Howard Johnson: tuba, baritone saxophone; Alex Brofsky: French horn; John Clark: French horn; Vince de Rosa: French horn; David Duke: French horn; Marnie Johnson: French horn; Claudio Pontiggia: French horn; Richard Todd: French horn; Tom Varner: French horn; Alex Foster: alto and soprano saxophones, flute; Kenny Garrett: alto and soprano saxophones, flute; Sal Giorgianni: alto saxophone; George Adams: tenor saxophone, flute; Bob Berg: tenor saxophone; Jerry Bergonzi: tenor saxophone; Bob Malach: tenor saxophone, flute, clarinet; Rick Margitza: tenor saxophone; Larry Schneider: tenor saxophone, oboe, flute, clarinet; Julian Cawdry: flute, piccolo, alto flute; Buddy Collette: woodwinds; Xavier Duss: oboe; Riener Erb: bassoon; Hanspeter Frehner: flute, piccolo, alto flute; Christian Gavillet: bass clarinet, baritone saxophone; Bill Green: woodwinds; Jackie Kelso: woodwinds; Marty Krystall: woodwinds; Anne O'Brien: flute; Charles Owens: woodwinds; Christian Rabe: bassoon; Roger Rosenberg: bass clarinet, baritone saxophone; Dave Seghezzo: oboe; John Stephens: woodwinds; James Walker: flute; Michel Weber: clarinet; Judith Wenziker: oboe; Tilman Zahn: oboe; Kei Akagi: keyboards; Larry Blackmon: keyboards, vocals, percussion; Delmar Brown: keyboards; Joey DeFrancesco: keyboards; Merv De Peyer: keyboards, drum programming; George Duke: keyboards, synthesizers, multiple instruments; Bradford Ellis: keyboards; Dave Gamson: keyboards, drum programming; Gil Goldstein: keyboards; Dave Grusin: piano; Adam Holzman: keyboards, Moog, synthesizer, percussion; Robert Irving III: keyboards; Deron Johnson: keyboards; Michel Legrand: keyboards; Jeff Lorber: keyboards; Jason Miles: synthesizer programming; Alan Oldfield: keyboards; Prince: various instruments; Joe Sample: piano; Bernard Wright: synthesizers; Jean-Paul Bourelly: guitar; Foley: guitar, bass; Randy Hall: guitar; Dan Huff: guitar; Earl Klugh: guitar; Michael Landau: guitar; Billy Spaceman Patterson: guitar; Vernon Reid: guitar; Mark Rivett: guitar; John Scofield: guitar; Mike Stern: guitar; John Tropea: guitar; Charles Ables: bass; Carles Benavent: bass; Michael Burnett: bass; Zane Giles: bass, guitar, programming; Darryl Jones: bass; Abraham Laboriel: bass; Steve Reid: bass, percussion; Mike Richmond: bass; Benny Rietveld: bass; Angus Thomas: bass; Don Alias: percussion; John Bigham: drums, percussion; drum programming, guitar, keyboards; Rudy Bird: percussion; William Calhoun: drums; Mino Cinelu: percussion; Paulinho da Costa: percussion; Erin Davis: electronic percussion; Kennwood Donnard: drums, percussion; Steve Ferrone: drums; Al Foster: drums; Omar Hakim: drums, percussion; Munyungo Jackson: percussion; Bashiri Johnson: percussion; Fred Maher: drums, drum programming; Harvey Mason: drums, percussion; Marilyn Mazur: percussion; Alphonse Mouzon: drums, percussion; Richard Patterson: percussion; John Riley: drums, percussion; Grady Tate: drums; Steve Thornton: percussion; Ricky Wellman: drums, percussion; Vince Wilburn Jr: drums; Steve Williams: drums; Michal Urbaniak: electric violin; Margaret Ross: harp; Xenia Schindler: harp; Green Gartside: lead vocals; Shirley Horn: lead vocals, piano; Chaka Khan: lead vocals; Zucchero: lead vocals; Tawatha Agee: backing vocals; Katrina Anderson: backing vocals; Bonne Bozeman: backing vocals; Chananja Bryan: backing vocals; Mia Dean: backing vocals; Mikel Dean: backing vocals; Rory Dodd: backing vocals; Mysheerah Durant: backing vocals; Akira Frierson: backing vocals; Myisha Hollaway: backing vocals; Tomi Jenkins: backing vocals; Noel John: backing vocals; Nathan Leftenant: backing vocals; Eric Myers: backing vocals; Erin Myers: backing vocals; B.J. Nelson: backing vocals; Ikeda Romeo: backing vocals; Cie Romero: backing vocals; Akelier Soogrim: backing vocals; Fonzi Thornton: backing vocals; Eric Troyer: backing vocals; Duane Thomas: backing vocals; Easy Mo Bee: programming, raps; George Gruntz: piano, conductor; Quincy Jones: conductor; others unlisted.

Tags

Miles Davis

Multiple Reviews

Jeff Dayton-Johnson

United States

Marcus Miller

Kenny Garrett

Gil Evans

Vince Mendoza

Terence Blanchard

Michel Legrand

John Lee Hooker

Shirley Horn

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.