Home » Jazz Articles » First Time I Saw » Dave Holland Circa 1976

Dave Holland Circa 1976

So it was without hesitation that I left my Utica College (NY) dorm on a night in 1976 and rushed to the auditorium for the scheduled concert of duet jazz. I was only familiar with Anthony Braxton through reading, but I was well aware of the bassist who would be with him, Dave Holland. That was my main interest in going.

To me, it was the Holland of the Miles Davis group that was taking different "Directions in Music," as the covers proudly proclaimed. Bitches Brew, In a Silent Way, Live at the Fillmore, the latter an album that baffled me at first, but that I grew to appreciate as my investigation into improvisation and exploration continued. The bass playing did not stand out to me on those records as anything other than being solid and appropriate for what was going on. But anyone who Miles hired had a special allure. He had to be a player wth something to say, I believed.

Got there early. Front row, right in front of the bass that had already been perched there. Amazingly, also perched off to the side was a saxophone, the largest I'd ever seen. You had to call it a sax, but it was a genetically engineered mutant. Supersax. An instrument for Goliath, or Paul Bunyan. It was cradled in a stand and probably stood six feet high or better, perched upright so all the player had to do was approach it and place his mouth to the reed and blow. It was FAR too big to hold. Literally dwarfed a baritone sax.

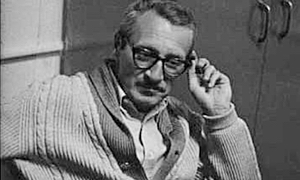

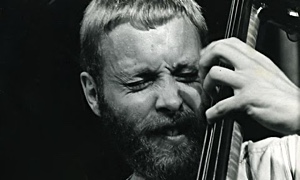

And out they came, the bespectacled Braxton and the bearded Holland. They began to create sounds, colors, shifting textures. It wasn't melodious, rather more like a journey. Maybe more like a painting. Braxton was sweet at times, and raucous at others. He veered off on new ideas. Took turns at odd places. Played phases, it seemed, just for emotion's sake, loud and boisterous. Even abrasive at times, but like he meant it... not a flub. The duo fed off each other, that you could tell. And the bassist, about four feet from me, had marvelous tone and technique on his upright bass. THIS, I said, is why Miles hired him. Damn!

The free-form jazz was easier to appreciate seeing the two communicate live. On record, I surmised, it would have taken more to sit pinned to the speaker to get the right feel, more laborious.

They were creating all right, and as much as I thought Braxton was talented on alto sax and clarinet, the bass was mesmerizing. Such tone. Strength. Assurance. And creativity.

When Braxton approached the beheamouth horn, Holland bowed his bass and tossed off eerie high and low screeches to accompany the low, bellowing monster horn.

Then... what's that?... It's—no, it isn't... yes it is... There... "Embraceable You." Fast and furious, Braxton taking great liberties with the melody, but that was it. Then he stopped, leaving Holland to play.

Geezus.

Fingers everywhere, up and down the neck. Notes flying out of the large wooden instrument like Joe Pass would fly over his much smaller guitar. Break-neck speed. Marvelous intonation. Everyone in the auditorium stopped in their tracks and the applause was awesome from a crowd that, honestly, was modest.

It was followed by more avant-garde stuff, then "The Song is You," played free-form by Braxton and again, a Holland solo. The memory of that, particularly the two jazz standards my ears were more accustomed to, stood out and I can still call upon that memory today. Too much for words. A memory that has not left me.

I stuck around, still buzzing from what I'd just seen on acoustic bass, and by the energy of the overall music. The Englishman came out to pack up the bass, and we chatted a while. Only minutes. My memory at this point about certain specifics gets assistance, because I dashed back to my dorm room and—being a young journalism student—scratched out a story for the college rag on what I'd witnessed.

Holland explained the mammoth sax was "a contra bass saxophone. There are only about three in the world and it's the only one that works," Holland said grinning. "It really works. No one else is crazy enough to carry it around" he chuckled.

We also spoke about the instrumentation—only bass and horn.

"Things are opening up to where virtually any instrument can be used in combination with any other," said Holland, who not that many years before had played in the renowned and experimental group Circle, with Chick Corea and Barry Altschul and Braxton. "No longer do you HAVE to have a drummer and so on. And I think it's a positive thing. It opens up tremendous possibilities."

It did, for a fact. And while I didn't understand everything I heard that night, I knew one thing: that bassist was incredible. It was the greatest bass playing I had ever seen live, and really, the best I had ever heard. Period. The dexterity and virtuosity were unbelievable.

I left that auditorium feeling that Holland, with no disrespect to the many great bass players I had discovered, was the most amazing bassist on the planet.

You do a lot of stupid things in college, for sure. Some on purpose and some... well... But I know that evening I wasn't stupid at all. Twenty-six years later my stance on Holland is exactly the same.

Tags

First Time I Saw

Dave Holland

R.J. DeLuke

Red Garland

anthony braxton

Miles Davis

Chick Corea

Barry Altschul

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Dave Holland Concerts

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.