Home » Jazz Articles » Music and the Creative Spirit » Rahim Alhaj: Iraqi Music in a Time of War

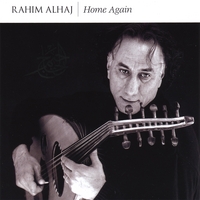

Rahim Alhaj: Iraqi Music in a Time of War

Music can connect and speak a universal truth that everyone can understand above and beyond language and logic and has the ability to transcend culture.

For a period of five centuries (750 - 1253), Baghdad was the music capital of the world. A music of elaborate ornamentations and modal rhythms that were rich, poetic and culturally beautiful. A music derived from the depths of ancient philosophies. There is even a belief that this is where melody was born, but now it lies in ruins with its culture and future in question.

For a period of five centuries (750 - 1253), Baghdad was the music capital of the world. A music of elaborate ornamentations and modal rhythms that were rich, poetic and culturally beautiful. A music derived from the depths of ancient philosophies. There is even a belief that this is where melody was born, but now it lies in ruins with its culture and future in question.From out of that culture is one of Iraq's greatest oud masters and composers, Rahim Alhaj who as a political refugee, now resides in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He was sent to prison twice by Saddam Hussein for playing traditional Iraqi music; intimidated and tortured, his spirit far too strong and unwilling to bend. Amazingly, he remains a humanitarian, an ambassador of the Iraqi people and culture, speaking through a common language of hope and compassion.

But there is another language that confronts Rahim and the people and culture of Iraq, and it is the language of fear; the fear from the perception that Middle Eastern and Arabic men are religious fanatics and cannot be trusted. It is a language and perception that Rahim knows all too well. Yet when most would find difficulty in sustaining their faith, he continues to believe in the goodness of his fellow man, and in the heart and soul of the human spirit.

Lloyd Peterson: I believe you were placed in prison. Do you mind talking about it?

Rahim Alhaj: I was imprisoned twice by Saddam Hussein and it was because of my political and artistic protests, which were against the Iran and Iraq war that began in 1980 and continued until 1988. There were high death rates and terrible consequences for both countries. I was a well known performer in Baghdad and used my music to explore and express the reality of my opposition to the government. Under this dictatorship, like any other, music and art was used by the regime to increase its political credibility and many artists had to choose between writing music to support the war and the regime, or refuse and have dire consequences. Subsequently, I was imprisoned and tortured by the government and treated badly like my fellow prisoners. As is similar throughout the world, the torture included fear, pain and dehumanizing tactics to force people to submit to the power of the regime in order to enforce control. I was not able to play my concerts and was put on a black list as far as musical activities related to my career.

LP: So obviously, freedom of expression was not allowed.

RA: Freedom of expression and criticizing or interpreting life is always difficult when you live under a dictator. Saddam took advantage of all art scenes in Iraq in an extreme way for propaganda purposes to support his rule and war. For example, there were hundreds of beautiful songs and poetry written for his cause (Iran/Iraq War, Baathist rule, etc). The artists had no choice but to follow the model of glorifying his policies or face severe consequences. Some left the country and refused to comply; others chose to stay and survive. In the end, a lot of outstanding art was created and supported, but under fallacious circumstances. Saddam also undermined the value and continuance of some traditional Iraqi music and culture, especially in the Shia south (marsh areas).

LP: In the US, during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Black musicians that played free improvisational music were investigated because it was thought that this form of music elevated the consciousness of the individual. Traditional instrumental music is not always welcomed in parts of the Middle East. Is there a similar parallel?

RA: Any kind of serious music is dangerous for dictatorial regimes and any music that you create without control, that doesn't flow or go with the agenda of a dictatorship, will be investigated whether it's direct critique or not. When I composed music in Iraq during the Saddam regime, they wondered how to interpret it, what my music was saying and what it meant. These were fearful questions for the government. So in Iraq during the 1980s and on, there were certain artists who were blacklisted by the regime and forbidden to be played or distributed in Iraq. Once I left, I became one of these and was happy to see when I went back in 2004 that they were once again circulating my music in the country and now watch me on television.

LP: Many people globally receive mixed messages with regard to Iraq. We know that the dictatorship and suppression that Saddam imposed on the Iraqi people was not acceptable but the messages are mixed on whether the U.S. led U.N. conflict has been beneficial for the people and future of Iraq. What is the feeling of those within the arts and other various segments of Iraq and Arabic societies?

RA: Well, there are definitely a lot of Iraqis who initially accepted the invasion as a means to topple Saddam and establish a new and democratic Iraq. This would have ended almost three decades of war and harsh sanctions as a result of the two Iran and Iraq Gulf Wars. There is no doubt that the US occupation and the end of Saddam's rule was seen as a window of opportunity for Iraq and a hope of freedom for many but obviously not for those who are loyalist in the Baathist regime which is connected to Saddam. There was also some resistance and resentment about the invasion of the country in general, since Iraq had a history of occupation by the British in the early part of this century which ended poorly. This initial hopeful outlook changed as the occupation dragged on and took a different shape over time and the Iraqi people began to wonder and question why their lives were not improving and were actually deteriorating under US occupation. Iraqis began asking questions about why the US forces were not leaving; what comes after Saddam and what should the country look like? Who would have power and how do we shape the country into a democracy that would fit our own culture and picture to include all Iraqi parties, resistance movements inside and out of the country? Iraqis started to strongly question the occupation and why it was not addressing their basic needs such as security, water, sewer issues, electricity, food and jobs.

However, other Arabs saw the occupation and invasion differently, depending on which political philosophy they follow or which country they live in. Millions of Arabs went to the streets to protest the invasion of Iraq and were afraid of its impact on the entire region.

LP: Perhaps the foremost threat to peace in the Middle East is the century old propaganda thrown at the American people that paints a racist attitude of Arabic peoples; that they are violent, fanatical and cannot be trusted.

RA: True. During the early 1900s, Arabs didn't have an understanding about what capitalism would mean versus socialism. The influence of the US in the region started in the 1940s and 1950s after World War II, in addition to when oil became a more important commodity. This was also at the same time that the Arab Nationalist movement was strong and Middle Eastern countries were focused on getting rid of colonialism and working hard to shape their countries in their own image, in a freer and more democratic way.

In America, the image of the Arab became tarnished around this period due to propaganda because Arabs were seeking to have their own destiny, out of western control, which included a separation from the influence of Israel and the Soviet Union. Subsequently, the image of Arab culture in America came to be shaped in a bad and incorrect way. Yet, many Arabs continue to differentiate between the American people, its culture which they respect and love, and the political and military agendas of the American Government.

LP: How much of this ignorance do you believe comes from racism?

RA: I think the superiority complex of the Western world comes from a position of power vis a vis Middle Eastern or other countries. When you have more power than others, sometimes you associate power with value and assume that the "other" has less value as a human being than you. For sure, ignorance leads to racism because if you don't have knowledge about something, it becomes less important to you. But at the same time, I think racism goes along with the potential of power and superiority since your perspective of the world is different. Even in the Arab world, you see a kind of racism versus power and economy that has developed over time that has led to racism. So in the Arab world, as an example, you can see rich Arab Gulf country citizens having more power than the poorer Arab countries, who also tend to see themselves as superior. So in order to be fair and see the big picture, you have to realize that the superiority of many Americans even goes against Europe and Africa; not just the Arab or Middle Eastern world.

And by not having the knowledge of another person's history such as their tradition, family and culture; it can lead to ignorance and racism (the assumption that you are superior). This currently adds to a lot of conflict in Iraq right now. So my conclusion would be that ignorance leads to racism, but at the same time, racism revolves strongly around the basis of money and power, which are related.

LP: You have spoken about the goodness of the American people but don't the people of Iraq have questions with regard to why we the US, continue to be at war with them?

RA: Yes, because in Iraq they believe that in the US there is some democracy and that this can lead to a change in the political and military agenda of the US government. I think there is a huge difference everywhere between the government elite and grassroots people. Saddam didn't represent me, and many people in the US didn't feel that Bush represented their interests or beliefs. In Jordan, it is true and in Britain, millions of people went to the streets against the war but their government didn't listen to their position. I believe that a gap between people and government exists, but Iraqi people believe democracy in the US can change disaster and make a difference. I hope they are right.

LP: Is there nervousness amongst the Iraqi people of the redesign of their culture and society through this war?

RA: I think Iraqi's have a strong feeling about their culture and their existence and yet, the recent war has a different aspect as far as seeing new culture through the soldiers, new restaurants, and new music through occupation that could reflect some nervousness about their culture being changed. However, I don't believe that Iraqis have fear of losing the essentials of their identity. They have much more fear related to their long-term security and surviving the day to day horrors of war. And in fact, because the Iraqi people have survived such a hard and difficult time over three decades, they have become more traditional than what has been usual in Iraqi society during this the 20th century, which was modern, open, and accepting to new ideas. I think conservatism goes deeply side by side when you have fear from the outside or for your existence. As long as you are comfortable, you don't have fear from change or the other; but if your very existence is in danger, you'll fear for your life and want tradition because this will give you more comfort and security. And because of this situation, it is clear that in recent years, the Iraqi people have become more religious and fundamentalist than they used to be.

LP: The politician has to sometimes compromise their own beliefs but the artist cannot compromise their art form, which usually doesn't reflect the compromised vision of leadership. That in itself is a clash of values and seems to be part of the challenge for what is at stake for the future of the Middle East. How can we get them to work together?

RA: To the extent of the truth and reality, there are some artists that compromise their dignity as well as the politician. However, if the politician has to compromise to achieve something good, that will be valid but sometimes a musician compromises just for their own sake, not just for their own dignity. This happened in Iraq where a lot of poets, artists and writers were used by Saddam's regime and lost their respect for Iraqi people and became the voice of the government and not their own or the people's voice. In fact, when I went back in 2004, I had a chance to see my friend who is a composer in Syria and he told me that he had no idea if he had the dignity to continue to live his life, because he buckled under Saddam and composed a lot of music for his regime and in support of the Iran and Iraq war which he was against. His own personal struggle reflects the complexity of being a musician under a dictatorial regime. In my case, when I refused to compromise my music and beliefs, I paid a high price.

LP: Today, political industrial powers are more controlled by money and business and less by the influence of leadership. But when you add religion how can one become more optimistic about the future of the Middle East?

RA: We have to be optimistic and believe in the power of music and human ability to change the current reality; otherwise we will lose our hope to have a better future. The spirit of humanity has always been struggling, but ultimately the voice of grassroots people will be heard when there is injustice and unfairness that shapes their lives. There is always struggle but at the same time, there is always a power over dictatorship with revolution and resistance against it, whether it comes from poverty, injustice and oppression and this is just part of human nature.

LP: Globalization can leave very little room for creative thought or acceptance of a creative culture. As the world moves further in this direction, is there a danger of various cultures being lost or forgotten? Are you beginning to see this today?

RA: I think that culture and tradition are always alive and fluid whether we intentionally seek to put it aside or not. Ultimately, the thought of cultural exchange in terms of globalization is a positive aspect but there are bad parts of globalization, especially the domination of one culture over another because of money, resources, or control of the media and communications. This impacts the ability of other cultures to survive. For example, if you look at the music scene in the south of Iraq, which was limited by the Saddam regime because the inhabitants are Shia, the regime put out propaganda that their art and music was "just" folk and not important to the picture of Iraq. But many Iraqis needed to hear the culture of the South which was unique in tone; maqam, expression, dialogue, music, and poetry and so forth. At the same time, I'm concerned about how long the people of the Iraqi south (sometimes dubbed Marsh Arabs) can continue their beautiful and time-honored traditions because many of the older teachers and scholars are not passing their traditions to new generations and this is further complicated by the security situation in Iraq specifically in the 1980s onward.

LP: For the better part of five centuries (750 - 1253), Baghdad represented the most prestigious center of musical arts in the world. Can you discuss this history, its importance and is there a danger of losing this history with the events happening today?

RA: Our history and our past is always there...the history of Baghdad was great and powerful and significant during the centuries of the Muslim rule. Al-Farabi, Al-Kindi, Ziryab, Itshak Musuli, all played significant parts in shaping music theory, structure and theme during this period, which had a major impact on music theory to the present. Iraq's present state of destruction and all that has happened to Iraq geopolitically, structurally, culturally, and humanly is a travesty and a disaster. In Iraq, down through the histories, we have always admired music so much and it has always been an important part of our culture. Now, Iraqis are in a time when everything is dark and a struggle—we struggle with war, death, survival, and sanctions. But when times are better, Iraqi music will definitely re-emerge and rise again to show its great history and the great creativity and ability of its contemporary artists who have survived and persevered even during these sad times.

LP: Is there a particular philosophy that has followed or influenced Iraqi music and musicians throughout history and other Middle Eastern cultures?

RA: Geographically, Iraq is important because it is the connection between the East and West of the Arab World and the Middle East. Turkey is in the West, Iran in the East and Iraq is the bridge for this region historically. From the times of Sumeria, Babylonia, Assyria, Mesopotamia; the people and its culture traveled back and forth. In terms of music philosophy, this goes to the maqam (mode) itself, what it represents and what musicians need to accomplish through this core for music. Music theory and practice says that maqams need to be played in the right time, season and day. Importantly, the complex theory surrounding maqamat, connects with philosophy and believes that music is the ebb and flow of life. A huge part of Iraqi music is based on the maqamat and maqam that exists throughout the Arab and Middle Eastern world and all of this has shaped Iraqi music. When we delve deeper into the meaning of music, we find several components to music including instruments and ensembles, old and new ideas and techniques. In Sumerian times, the oud started with just three strings, moved to six and today has 11 or 12 which allows the scope and possibility of communicating through music to expand. In Sumeria, which is the first known civilization in the world, present day southern Iraq music was connected to nature, Gods, Goddesses and everyday life and had deep philosophical meaning behind it.

LP: Is your work and music a reflection of Iraqi culture and religion and do you feel personally tied or connected to that culture?

LP: Is your work and music a reflection of Iraqi culture and religion and do you feel personally tied or connected to that culture?RA: My music and work is a reflection of Iraqi culture. When I first learned to play the oud and the maqamat, I was unconsciously learning about my culture and it's past. Our music and poetry teaches us about our culture and our culture is our womb which surrounds and births us and this includes our first impression of music. In the beginning, I discovered music and the process of learning but once I became more aware of my music and the world, I began to express myself in a different and more complex style. This defined my core beliefs, my sensitivity and creativity according to what I interacted with.

When I became involved politically, I became more aware of the environment around me and I used my music to interpret my reality and experiences. In my compositions, I constantly concentrate on combining life and music together to make them closer and to connect them. I grew up in a culture that differentiates between vocal songs and music. In Iraq, we admire poetry more than anything else and we are very attached to words and connect with them before we connect with the music. Additionally, in the Baghdad School of Solo oud, which I follow, I challenge myself to use the extensive power of the solo oud and through my compositions, tell stories, and relay emotions and experiences through music alone.

LP: I believe that you studied under Munir Bashir. What did you learn from him?

RA: LP: Yes, I did study under the great oud master Munir Bashir at the Baghdad Institute of Music (the Julliard of the Middle East). The most important message that I received from him was when he told me over and over: "Rahim, don't underestimate or undervalue the power of your instrument and playing. Honor it always and don't compromise your work and talent." That is why I have always refused to play background music or play in "non-professional" venues, even when I have been a starving artist.

Another important lesson he taught me is: "music is not only noise; in fact silence can be the most powerful part of a musical arrangement." The overall most important influence on my development as an oud musician and composer was, in fact, Munir's brother, Jamil Bashir. Although he died when I was young and I never met him, his style and compositions left an indelible impact on the way I think about the oud and composing in terms of contemporary and cutting-edge oud playing. People who know his work have compared me to him over the years.

LP: What exactly is the meaning and nature of music to you?

RA: From the first minute that I picked up my oud when I was a little boy, I decided that this is it. I am a musician and this instrument will be with me to the end. The instrument deeply touched my soul and I started playing and practicing for unlimited hours. I found the perfect way to express myself was through the instrument and that is what has built and structured the meaning of my life. As I became older and more aware of the power of music and how to engage it politically, musically, humanly and existentially, there became an even more powerful connection between myself and music.

In the end, I find myself so close to finding the meaning of life through music, including the deep meaning of what it means to be a musician. The meaning of being a real musician is the essential core of my life, knowing that through this power, I can truly make a difference. Initially, I experienced this difference while growing up around my family, friends, and teachers. My dedication grew and became stronger as I understood that this was what I needed to do in life and that being a musician makes life livable. Music is the vocabulary between the world and me and I'm constantly working to be able to understand life and the world better and to be able to better communicate that understanding.

LP: Does your music reflect struggle?

RA: My music is all about struggle and it is my biggest challenge; to talk about struggle in many ways and many shapes. It's the struggle to live well and the struggle for survival; the struggle for a future with peace.

LP: Is it a music of resistance and a fight for human rights, freedom and dignity?

RA: My music has always been about resistance and a fight for human rights, dignity and freedom. I grew up in an Iraq that became a dictatorship under Saddam Hussein and much of my life was colored by this. In Iraq, my life and music reflected the reality of a political struggle and I tried hard to portray the reality of the Iraqi people, their dreams and struggle for freedom, dignity and human rights; even just basic needs. However, I suffered the consequences (imprisonment, torture, exile). In my new home of America, I continue to talk about this situation through my compositions, music and dialogue with the American people which overall has been very well received.

LP: How important is humility?

RA: Humility is essential to the creative essence. Humility or humbleness is at the core and depth of truly creative people, such as musicians and artists. The more creative you are, the more truly humble you are. A good human being is inside a good musician. There's an Arabic saying which goes, "Human beings are like trees...the ones that are older and fertile, heavy with fruit, bend low. "

LP: I think we would agree that ignorance is one of the greatest challenges that people of Middle Eastern descent face today but does it also affect the music?

RA: I would agree that ignorance is the biggest challenge for Arabs in America. And as an example, my instrument is very unfamiliar in the US. My strategy is to try to compare things and put them in contexts to educate people so I talk about the oud and the related lute and explain the linguistic similarities and how one became the other. I explain that the oud is the grandfather of all stringed-instruments which started 7,000 years ago in Sumeria (southern Iraq).

What can sometimes be frustrating is that because westerners, and especially Americans, have no knowledge or context for oud playing (even music reviewers and specialists), they don't have an appreciation of the level that I'm at or the virtuosity of what I'm doing. Additionally, they don't understand the fact that I'm exemplifying and creating an entire new school of oud theory, The Baghdad School of oud, which was developed by Munir Bashir and the founder of the school, Sheikh Muhaddeen Haydar. It is focused on the solo oud concert, the oud being powerful enough to stand on its own as it did in ancient Sumeria and the Abbasid period in Baghdad, before it became merely a folk instrument as part of an ensemble accompanying a singer. Because of this situation, I never really receive credit for my very unique style and level of oud playing and the complexity of my compositions. People just love my music and believe they're hearing what traditional oud music sounds like. But only my advanced Arab listeners can understand the real difference and newness of what I'm promoting, still based in old tradition.

All of this is part of my challenge in living in America—a culture different from my background in so many ways but also why I feel it's is so important that I am here and that I stay here to take on responsibility of changing some of the ignorance and some of the stereotypes and highlighting the sophistication of Iraqi music, poetry, culture, language and human interaction.

LP: There appears to be a correlation with artists and higher awareness levels. As an example, there are many that seem to have the ability to look past and beyond cultural differences. They have reached a creative place or reality where prejudices don't seem to exist in that reality. Have you noticed this and can it be attributed to the power of music or is it perhaps from a particular type of spiritual or cultural enlightenment?

RA: Just by the nature of their work and who they are, artists and musicians are always in need of communicating and finding new concepts, perspectives and creations. Because of this special need, they seem to have developed a greater sensitivity and desire than many others in "mainstream society" to have cultural and emotion exchange and intuitively understand the need for bridging, collaborating, sharing and understanding across and within cultures to synthesize ideas. I believe in the universal artist movement that somebody in another part of the planet is doing the same things, even though in a different style, but with higher intention to research and discover new aspects to express themselves.

LP: You have said that as human beings we need love, we need compassion, and we need peace. Can you explain?

RA: I can not imagine our world without these concepts. Can we imagine our world living in hate instead of love, living without compassion— unfeeling, cold, with a lack of caring for each other? How can we envision or accept that and consider ourselves human beings?

LP: Does music has the power to transcend culture?

RA: Music can connect and speak a universal truth that everyone can understand above and beyond language and logic and has the ability to transcend culture. It can be a powerful force that can change the face of political status quo.

LP: Can musicians set an example that we all want the same things from this life?

RA: Conceptually, musicians could play this role, but I have to say that we're all individuals, and not all artists and all musicians as a group set good examples. Some would rather just have financial acclaim; some would rather play traditional and safe music and not challenge the status quo. On the other hand, there are many of us who love music and play music because we think the contemporary situation is most important and are urgent to impact and to make our music meaningful for current human struggles and the human situation. I believe this, and my compositions all speak to ongoing and modern human stories and give voice to those oppressed humans who have little or no ability to get their voice heard. We have to speak and live and make music in the moment. I think many humans have this view and not just musicians.

LP: As conflict and turmoil continue to confront our very own survival, does music have the power to be the language of peace between all people and societies so all can live in peaceful coexistence?

RA: Music can definitely portray love, compassion and peace and these are my three most important themes and messages of my music and my life. With every composition, I try to grasp and communicate the meaning of these concepts. Most importantly, the time is very important for peace and justice around the world and at this time, this message has to be massively communicated so the message will be received and affect change. The language of music has the ability to spread this message powerfully and to reach people deeply in their hearts and souls more effectively than logical thought or discussion. Music is abstract and reaches you on a different level of awareness and that's why day by day, I'm more convinced of the power of music to establish peace in a very strong and profound way.

LP: Do you foresee a time of understanding, tolerance and peace between all cultures and people?

RA: I hope for that. I always hope for that and that's what I'm working for and what my vision is. We're always talking about our differences and not our similarities. Instead of concentrating on our differences, we need to concentrate on our unity and how can we build our world in a better way instead of destroying it and seeing our world in a way that is hard to imagine. It's our responsibility to live together in peace rather than war, to create love rather than hate. It's our responsibility as humans to envision this in the world and to work towards it. This is the most significant thing; to see the world working towards beautiful harmony.

LP: What is beauty to you?

RA: Beauty to me is creating a piece for an orchestra with all members participating while feeling proud despite the differences of the origin of the instruments or the musicians. Beauty to me is when you see Iraqi children's faces living and smiling and looking forward to their next day. Beauty to me is when I see children holding their school bags and going to school knowing they'll be coming back home safely. Beauty to me is to see the world living side by side in harmony with no racism, no hate, no violence, and no war.

This interview will be included in the future book publication by Lloyd Peterson, Wisdom Through Music. He is also the author of the book, Music and the Creative Spirit.

< Previous

Evergreen

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.