Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Nels Cline: Intrepid Guitarist

Nels Cline: Intrepid Guitarist

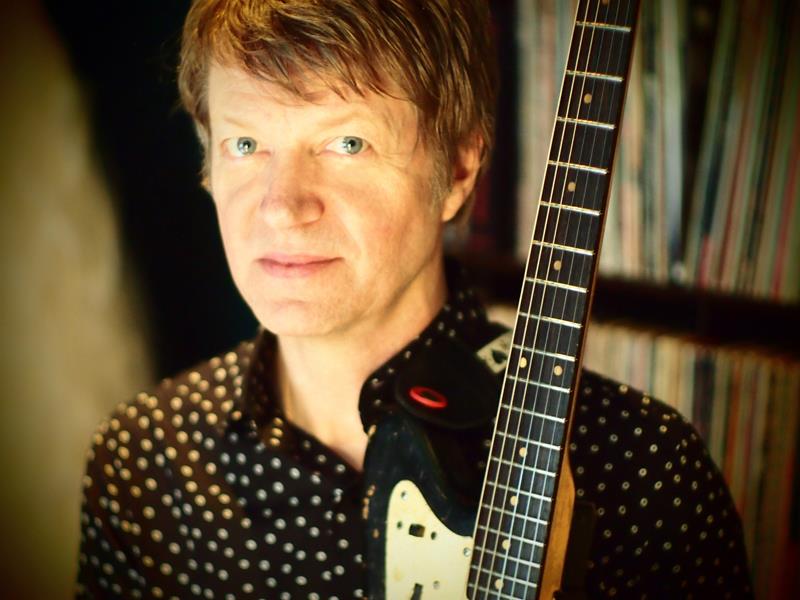

Courtesy Nels Cline

My idea is that if somebody ever comes to my music, that it adds up to something kind of intriguing and maybe there is some weird kind of consistency that emerges. But it's definitely not going to be obvious.

—Nels Cline

Much of this has to do with Cline growing up in the '60s and early '70s, when there seemed to be fewer rules and the music industry had yet to become so directly involved in defining what was heard. "The sort of Catholic booking policy of one evening," explains Cline, "the fact that hippies liked blues, they liked gospel, they liked folk, and so they mixed it all up, that's how you got those great stories of Miles Davis opening for Laura Nyro at the Fillmore; I meant it's crazy, you can't imagine that kind of stuff now. Audiences wouldn't be able to handle it. I think the best part about that, whether it was all great music or not, was that the audience was really patient, and the bands were patient enough with the process of their own music making to take the time and cast about. It's so cut to the chase everywhere these days; it's not as exciting to have shows where everything is so predefined."

Wilco

While Cline continues to pursue a variety of avenues these days, and still maintains a solo career with his trio The Nels Cline Singers, he spends most of his time touring with the alternative group Wilco. When Cline joined Wilco a few months back some people were surprised at the move, but in context of Cline's voracious musical appetites, it should come as no surprise at all. And while there has been some misrepresentation of Cline's role in the group, he is clear that this is not a case of being merely a touring guitarist; this is the beginning of a longer-term relationship. "I was in a rock band called The Geraldine Fibbers in L.A.," Cline says, "which is how I met my sweetheart, Carla Bozulich. We were opening for a band called Golden Smog, which was guys from Wilco, The Jayhawks, and Run Westy Run, doing a side project of cover songs. They were doing a couple weeks tour in the Midwest and we went out opening for them. The Fibbers kind of cottoned to Jeff Tweedy, although I honestly didn't give a damn about what any of them were doing except that they had great taste in cover songs, and I felt that Gary, the guitarist from The Jayhawks, had a great guitar thing, and Jeff obviously had this weird kind of point of view, this charisma about his singer/songwriter personality, but it wasn't really my thing."But Carla kept in touch with Jeff," Cline continues, "and, as I've discovered, Jeff was keeping in touch with what I was up to, buying my records and listening to my playing, which he really liked. So Carla opened for Wilco on some shows last year, and I was in the band, we all re-established connections and when Leroy Bach left, Glen Kotche, the drummer, and Jeff thought, 'What if?' So they called me up and, as mercenary as it may sound, I was about to get a day job. I was completely at my wits end, working constantly but not making enough money to pay my bills, driving up and down the coast, not making any money in spite of the fact that I was constantly working.

"I'd turned down a lot of things in the past that could have been lucrative," concludes Cline, "but that just weren't interesting, but Wilco is a band that, to me, has become much more popular as they've become much more interesting. Jeff called Carla to see if it was OK to ask me to join, because I'd been playing with her. She knew I was probably going to have to do this because it was going to actually be a living and not be horrible. She probably half expected me to turn it down because I was always turning down things that would have made money but that I didn't think were interesting. Anyway, I said yes to Jeff and, frankly, it's been a blast."

Watching Cline onstage with Wilco, there's absolutely nothing paradoxical about his being there. While his role is supportive, he still gets his opportunities to stretch out and wail, albeit in a more "rock and roll" context. "I think the reason somebody like me is good for the job is that I really want to fit into the orchestra," Cline explains. "They're a very orchestral band. I just kind of range through their earlier material, because it's more singer/songwriter oriented, but the new material is very specific, I'm playing very specific parts every night. And then I have moments where I get to go off, but you know they're rock band moments, just a few seconds here and there. But it's rewarding because the music is so expressive and it's so wide-ranging stylistically.

"I also think the band is very disciplined in the way that it approaches being an orchestral type of band," Cline continues, "yet there's a certain degree of freedom. In that way it's not unlike groups like The Band, where there's constant riffing going on, tight and loose at the same time. And the funny thing is that during these shows, everybody thinks the band is so unbelievably tight, and I think it's because it's disciplined dynamically. Everyone knows when not to play. But while I have some freedom I also like to be part of something that seems ultimately meaningful. I hate to be just wiggling my fingers all the time. Some people are perplexed, other people think it was an obvious progression, others are completely mystified. Some people really hate the idea of successful bands; other people hate the idea of bands in general. Other people hate the idea of chords. For every person there's something that's potentially taboo. I don't have these boundaries, and yet it has been difficult not to play with Carla, and to not do as much of my own music. But I haven't been able to afford to do my music for a couple of years anyway; I was losing a lot of money and creating an inordinate amount of stress.

"Jeff's feeling is he wants this to go on for ten years," concludes Cline. "I think that the band chemistry is really excellent, I'm really curious what the writing process will turn into, and I think that Jeff wants to get to that sooner than he'll be able to, because it's all about shilling for the new record, A Ghost is Born, which was totally done before I joined. I saw some stuff in the press, the other day, where I was referred to as "touring guitarist," but that's an assumption, that was never the assignment."

And there's no question that, while Cline is required to fit into a certain amount of predefinition with Wilco, he isbringing his own personality to the band, and causing things to change. "Jeff's a really sharp guy," says Cline, "and he's concerned that the emphasis of the band will be too much touring and constantly playing the same songs, so I think he's trying to figure out how to lighten up. I overheard him say that the recorded versions of some of these songs seem very outmoded now. The thing that's happened, from my standpoint, is that the starkness of some of the tunes is perhaps even starker and the tunes that rock are ramped up, they're ramped way up now. And Jeff's really inspired onstage these days."

Influential Recordings

Cline's breadth of style is reflected in the albums that he cites as influential, albums that date back to his growing up days, but extend well into his adult years. "Certainly Turn, Turn, Turn by the Byrds would be the first one," says Cline. "I was ten years old and my twin brother [percussionist] Alex and I were hanging out with these n'er do wells who would sit around their apartment unsupervised, their father was never home, and we'd smoke cigarettes and listen to Turn, Turn, Turn. Somehow it was a ritual, and I became enchanted by the whole vocal sound, the guitar sounds, everything, so The Byrds were my first big inspiration. My brother was really obsessed with The Rolling Stones, they were his band, and The Byrds were my band, you know with the twin thing one would define one's self by predilections, trying to be an individual. But of course, as a result, I did hear a lot of Stones and also absorbed all of that. I'm particularly fond of Their Satanic Majesties Request, and still listen to it to this day; in fact I went through a phase over the last year where I revisited it extensively."The next big record would have been Are You Experienced, by The Jimi Hendrix Experience," continues Cline. "Just to explain, my brother and I were obsessed with rock and roll after we were about eleven years old, it would take us two weeks to save up our allowance to buy a record and we'd just go and spend it on records, it was the only thing we spent our money on. Our friends stopped talking to us because we didn't want to go bowling anymore, play football after school or whatever. In those days there was no FM underground radio quite yet, at least that we could pick up in L.A. But this was an incredibly exciting time for music; this was when The Yardbirds were happening. 'Happenings Ten Years Time Ago' was on the radio, which was transformational in the extreme, really exciting stuff.

So when Are You Experienced came out we just knew by the cover that it was going to be the coolest record ever," Cline continues. "But we had bought a lot of records thinking that they'd be cool because of how they'd looked, and were severely burned, so somehow I had held off, same went for my brother. Anyway, one day we heard 'Manic Depression' on WKHJ, the top 30 radio station, AM, which is still a mystery to me because it wasn't the single, 'Purple Haze' was the single, and we knew immediately—I remember it so well because we were listening to it on the hi fi in the back room of my folks' house, and as soon as it came on, the sound of the voice we just knew the record, and the sound of 'Manic Depression' pretty much was right up there with 'Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,' 'I am the Walrus,' it was absolutely mind-expanding, transformational music making. So that was big, so of course I went out and bought the record as soon as possible, and then frankly, Axis: Bold as Love I liked even better as an album, then everything—Electric Ladyland, Cry of Love, War Heroes, all became huge records."

In terms of jazz, the first artist to make a big impression on Cline was John Coltrane. "Then there was 'Africa,' by John Coltrane," Cline explains, "which was the big 'ah-ha' experience. After junior high a friend of ours loaned my brother Coltrane's Greatest Years Volume One, which he had bought for his dad's birthday. His dad was this Bohemian poet, and he thought Alex would like it because he liked all this Frank Zappa stuff that was instrumental. And we heard 'Africa' and we were just absolutely devastated, we didn't know what to do or what to think anymore. The whole world changed that day, seriously, it's insane, and I've tried extensively to explain what was the attraction to that piece, and the mystery of the sound of that tenor saxophone. There were no electric instruments anywhere on that album, no guitar, and here we were just mesmerized. That was big, and it led to me buying as many Coltrane records on the Impulse! Label as I could get and gradually working my way back into Atlantic and Blue Note and Prestige.

"Paul Bley then became really huge for me," Cline continues. It was the Open to Love record that I think attracted me, then I went back and heard the trios with Gary Peacock and Barry Altschul, and then also Paul Motian and Mark Levinson and all the different trios. The Rambling record, Blood and Ballads, with Gary Peacock, all those records; I became a complete Paul Bley obsessive. I got this huge crush on Carla Bley around the same time, and started listening to a lot of her stuff—my God, she was so hot—so Paul Bley became, strangely, really, really important to me and the ballads that Annette Peacock wrote, those free-floating, really dark amorphous ballads, became a kind of paradigm where I was thinking about it as an ultimate kind of way of making music and I was trying to figure out how to imitate that feeling with a guitar trio, which I still do on almost every record."

With complete voraciousness, and total abandon, Cline soaked up everything he could from as many different sources as possible, and does so even to this day. " Marquis Moon by Television was huge," Cline explains, " Bad Moon Rising by Sonic Youth was massive. I'd heard their first record when it came out, the one just called Sonic Youth on Neutral, but I wasn't really blown away by it; it was when I heard Confusion is Sex at the record store, at Rhino where I was working for years, and it really snagged me, but then when Bad Moon Rising came out I became a full-on obsessive. I've missed barely a show since those days. I just saw them in L.A. a couple of weeks ago. And of course we've become friends over the years and I've recorded with some of those people. Those were important records.

"Patti Smith's first record, Horseswas also really important," Cline continues, "I started getting more interested in rock and roll again. Oh, I forgot some of the most important records of my junior high school years, the first three Allman Brothers Band records. When underground radio started up, WKPPC in Pasadena, we could barely get it in West L.A., but one day, before it came out they played the first Allman Brothers record, an advanced pressing, and that was it, I knew I'd found my holy grail of bluesy, jazzy, tasty, dark; the perfect band.

"I used to love Johnny Winter," concludes Cline, "especially that album Second Winter, my favorite. I was also way into Traffic, the second one just called Traffic, and John Barleycorn Must Die, those were huge. Neil Young; I was fourteen and I wanted to beNeil Young, which was a hard task, because nobody could be that cool; at the time, I thought he was the coolest. Because an outgrowth of my interest and love for The Byrds was Buffalo Springfield, that led me to Stephen Stills, who is still one of my favorite singers and guitarists, but also, sadly, one of the biggest disappointments, he lost it so early, but still when I hear those guitar fills on 'Wooden Ships'; playing with Wilco has actually made me revisit a lot of that music that was incredibly seminal for me."

And, of course, the allure of the early fusion bands was not lost on Cline, including Weather Report's self-titled debut, Live in Tokyo and I Sing the Body Electric. Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi band, in particular Crossings, was influential, as were a number of Miles Davis records including Bitches Brew, Live/Evil and Big Fun. "My brother bought the first Mahavishnu Orchestra album when it came out," says Cline, "but that was his obsession. And I saw them live and of course they were devastating, it was like having all your body hair singed off in one fell swoop, it was just so scary in a way. But for me, a lot of that music just doesn't hold up now, I hate to say it; it's no disrespect, that music was important."

Equally important to Cline were seminal albums in the ECM catalogue, including John Abercrombie's solo disk, Characters. And Ralph Towner's work in and out of the genre-bending group Oregon would have a monumental and lasting effect on Cline, greatly informing his work with the similarly acoustic-natured group, Quartet Music. But the huge diversity in his musical tastes would sometimes create a palpable dilemma for Cline. "I really think that when I started my first trio in 1989," Cline says, "the first group I ever led was also the first time I ever confronted what had been an almost debilitating mental dichotomy between jazz and rock, between soft and loud, acoustic and electric, all these things, which were at war in my inner being for my entire adult life. It was so upsetting that I almost quit music, I just couldn't handle it anymore, I didn't know what to do, I wasn't happy with electric guitar for a long time because I didn't know what to do with it, that's why the acoustic guitar emerged as more satisfactory to me. So when I started my trio the idea was that I just didn't care, I'd do things that I felt like doing."

And doing what he feels like doing Cline is just as inclined to play in a rock group as he is a more straightforward jazz context or, in the case of his own work, some strange kind of blend of the two. "There's a certain place I like to go to when I'm playing, says Cline, "and that's why I like to play in rock bands, because I can usually get there faster. It has to do with complete immersion, a certain kind of lack of dignity if you will. One of the reasons I played in rock bands for years after playing with Quartet Music for so long, was because I was tired of people just sitting down and listening. Before that, all I wantedto do was to play for people who would sit down and listen because nobody was listening. So I think that it's not just my personality, but also inherent in the instrument, that I can go into a lot of different domains, and it has been interesting to lead almost a double life. For example, playing with Bobby Bradford; I mean I'd do gigs once in a blue moon with Dr. Art Davis, I mean they had no idea what I was doing with Mike Watt or with The Geraldine Fibbers; yet some of the rock people are actually interested in my jazz life, especially now. But nobody knows who Vinny Golia is, and I've been playing with the guy for twenty-seven years. My idea is that if somebody ever comes to my music, that it adds up to something kind of intriguing and maybe there is some weird kind of consistency that emerges. But it's definitely not going to be obvious."

The Left Coast Scene

Over the past twenty-five years, through associations with Vinny Golia, Cryptogramophone Label owner and violinist Jeff Gauthier, his own brother Alex, and a host of others including Wayne Peet, Steuart Leibig and G.E. Stinson, Cline's name has become synonymous with the more avante-leaning west coast jazz movement, the so-called Left Coast scene. And while people are quick to look for defining characteristics of that scene, especially in comparison to the downtown New York scene, Cline is less inclined to think of it as a matter of style, rather more a matter of place."I think that there's no doubt," explains Cline, "and I've had to answer this question a lot mostly because I obviously play in New York as much as possible so people think I have some insight, that obviously everybody has looked to New York at some point or another. They've said, 'I really love this John Zorn guy, I want to know more about the downtown scene,' or whatever it is, and certainly John has brought a lot of people to that music. He's kind of a rock star in his genre. I wanted to move to New York in the early 70s, I was dying to move there, I thought it was the greatest place, just because I liked the feeling there. But I knew that I couldn't survive there, because I had no self-confidence. But obviously New York has the history, New York has the commerce, it has the depth, you know, they have a deep bench, there's a lot of players there, there's a lot of competition, and as a result of there being commerce there it gets covered in the press, people know a lot about these players, whereas they don't know about a lot of the players in other cities.

"So that's what differentiates it from any other place," continues Cline. "It's always going to have some kind of cachet and it's going to be easier to get a gig if you're from New York playing weird music than it is from anywhere else because people are basically going to think you're going to suck if you're not from New York. If you're from New York you must be good. That's the biggest difference. I don't want to say musically whether there's much of a difference or not, but certainly whether people want to admit it or not, there's a blueprint that's pretty New York-esque that a lot of people have looked to, even if it was only for one part of their life, it had an effect, an impact on how they think about constructing a piece, or playing their instrument, whatever.

"That said," Cline concludes, "John Carter and Bobby Bradford had a huge impact on me, they were coming more out of the Ornette thing, and Ornette's thing is not a New York thing, even though he moved there. He was in L.A. for years, but he's a Texas guy, totally Texas, so is Julius Hemphill, a total Texas guy, and Dewey Redman. But also I got really interested in the European jazz scene in the '70s, with all those ECM people. That had a huge impact, I think, on the world, you can hear the lasting resonance of players like Jan Garbarek; now other players, even session guys, play like Jan Garbarek."

Musical Resonance and Musical Audacity

Cline's first trio lasted, with some personnel changes, for nearly ten years, releasing albums on the German Enja label as well as the smaller independent, Little Brother. Reconciling Cline's jazzier predilections with his desire for a broader reach that also incorporated his rockier sensibility was a challenge, and something that the first trio wasn't always completely successful at combining in a way that his current trio, The Nels Cline Singers, can. But one thing that was surprisingly clear from the start was that Cline, clearly a facile guitarist who could shred and burn with the best of them, wasn't about making records that were meant to appeal to the more technical side of the instrument. "The criticism that people who like hearing me play exciting guitar have of some of my own records," says Cline, "is that there isn't enough exciting guitar on them. That's because I don't like to hear myself do a lot of fast finger wiggling on my own records. There's a friend of mine in the record industry who loves my playing, but tells me that I don't solo enough on my own records and it's actually very scrupulously constructed so that I don't. I want to listen to what I want to listen to, that's what I record, and so I just try to do what I think will be really nice to listen to and it is all, for me, more emotion-based rather than based on any kind of conceptual novelties; certainly not based on any tradition per se; I just like to feel like something."I aspire to a balance of autodidact fascist self-obsessed rigidity," Cline continues, "and then writing for everyone to enjoy contributing their personality to the orchestra and having freedom, no doctrine. There are blowing pieces," continues Cline, "the non-doctrinaire pieces. But the other ones are very much calculated to have some kind of an emotional resonance that I would associate something with, and because I associate something with it, I naturally assume that it, at least, has the potential for universality because that's how art infected my life. So I go by not just music, but all the different ways that art and culture have transformed my way of thinking about the world and myself. I just use that as my yardstick; if it's good enough for me and I can live with it then it's going to have to be good enough. And I think that's not something a lot of virtuoso musicians do, because I think they measure themselves against the greats of all time, and as a result don't always express themselves, they're too daunted to, or they really don't feel they are allowed to be creative because that would be egotistical somehow."

Still, as much as Cline's records are about pure emotion and less about the logistics of performance, his broad talent and distinct personality always seep through. And while Cline's music is often without overt reference points, some people do find the need to draw comparisons. "I've gotten a lot of flak," explains Cline, "from some people who say, 'Why do you think you're so hot to make your own records? You're not as good as Wes Montgomery, or so-and-so.' But I don't think music should be a competitive or comparative thing; it certainly never was to me. To me the more the merrier, and to me the idea of the loft jazz scene, the so-called DIY aspect of that, which is totally identified with in the punk world, it's the same ethic, it means that everybody can do something, and you never know what's going to have an impact.

"Listen to a band like DNA or even Sonic Youth," continues Cline. "If these guys didn't make records or play gigs, I wouldn't be thinking about music the same way. It's a very simple equation; I'm not looking for the ultimate chord voicing everywhere I go. Someone like Lenny Breau totally inspired me in terms of his massive technique, but he also had an aesthetic about harmony that was unique to him, and not just his chops. Same goes for what my friends call primitive musicians, and some of them are compartmentalized, creating a ghetto for them called the unschooled musician, as opposed to the schooled musician. But I have to say that I categorically reject this, it's the antithesis of how I view the world and it's also the antithesis of how I think about creativity in general. To me everybody is allowed to do anything they want, I just don't have to like all of it. But if we didn't all do it nothing would change. It's some of the crazy people that usually force us all to go somewhere else because nobody else has the courage to be out there.

"I got to hear Derek Bailey in Barcelona this year," Cline concludes, "and I feel really good that I got to tell him that because of his courage, his taking the hard road, and making the courageous choice to be himself, he made it easier for all the cowards like myself, who would never have been able to do what he did. He's the father of all those years of investigation that we've all benefited from. I don't have that kind of audacity, that kind of tenacity; I'm just not that person, so these are the people that push the music forward."

The Nels Cline Singers

With the forthcoming release of The Giant Pin, Nels Cline's current trio, The Nels Cline Singers, has evolved even further from their first record, '02's Instrumentals. The trio includes percussionist Scott Amendola, well-known for his work with artists including Charlie Hunter and TJ Kirk, but also carving a name for himself as a leader with his own band, The Scott Amendola Band, including last year's remarkable album, Cry, which Cline also played on. The third member of the trio, bassist Devin Hoff, may be less well-known in a larger context, but is one of the busiest bassists in the Bay Area scene."I met Scott Amendola," Cline explains, "when I played my old concert series that I used to have on Monday nights at The Alligator Lounge in Santa Monica for four years. My old trio anchored the series, and one of the first people to really bounce back and forth between L.A. and San Francisco, and who was pretty much the single most important person in getting me acquainted with who was playing in the Bay Area, was this man Phillip Greenlief, a woodwind player. And Phillip brought various bands down, and one day he called me up and wanted to bring a duo with a drummer, and the drummer was Scott. Scott totally blew me away. Then Phillip came back with a trio, with Scott and Trevor Dunn, and we did a double trio at the end of the night; his trio plus my trio, and Scott and I, there was just a good feeling there.

"Gradually he started doing more and more things that I was aware of," continues Cline. "We ran into each other when he was on the road with TJ Kirk, and then one day my friend G.E. Stinson was putting together an improvising group for a gig, he wanted to have Steuart Liebig on bass, and me and him and a drummer, and I suggested Scott, because he wanted somebody who could groove and somebody who could improvise, and Scott's got a deep groove and beautiful sound. G.E. said, 'well do you think he'll do it?' because although I knew that G.E. loved Scott's drumming, he'd have to drive down here to do it and make virtually no money. So I said, 'Well, all he can say is no.' So he came down, he did it, and that's what became L. Stinkbug. So Scott and I started playing together in L. Stinkbug, but that was sort of a rare event. As time went on Scott and I would start emailing each other, and he would always say, 'You know, I want to do more with you, I don't want to do just L. Stinkbug, we never play enough.' And I thought, 'How can he be saying this, he's the busiest man in show business.'

"After The Geraldine Fibbers," Cline continues, "I was kind of waiting for Carla Bozulich to come up with another project; we had a duo we were doing, but it was really esoteric, so I was kind of biding my time. My trio had fallen apart, I'd done one project in the meantime called Destroy All Nels Cline, and it was just a very specialized and limited idea, a very unique project. But it wasn't a real working band. I finally decided, after I hadn't done anything of my own for like three years with my own band, that was really a working band, that I should do another trio. Scott finally sent his millionth email saying we have to do more together, he was actually on the road then with Jack Walrath in Europe, and he was like, 'We have to play some music!' So I said, 'Does this mean that if I start another trio that you'd want to play drums?' And he said, 'Absolutely!' followed by three hundred exclamation points.

So I thought," continues Cline, "OK, this'll be interesting because he lives in Oakland, but I just didn't care anymore, I wanted to play with whom I wanted to play with, and I thought Scott was one of the best so I asked him, 'Who should play bass, I want an upright bassist, it may as well be somebody in your town because I don't know anybody who'll do it down here in L.A. on upright.' He said, 'Well, there are two guys I can think of, but the guy I think would be perfect is this young guy named Devin Hoff, not only because he's good, but because he already loves your music, he has all your records.' I'd never heard of him, but I said, 'OK, fine,' and we booked a gig, got together and played the gig.

"People can't believe I didn't audition people," Cline concludes, "but if Scott thought he was good I thought he was good. Turns out that I had met him before, he was playing with Joel Harrison one day in L.A. at my brother's concert series, and we had had a whole conversation about Mike Watt. He was all into punk rock, was a complete jazz head, and basically fit the bill and that's the story. He's done a lot of things, he's played with Graham Connah, and still does quite a bit, Connah's a genius composer and pianist in the Bay Area, kind of an elusive cult figure, has some records out on Phillips Greenlief's label, Evander Music, all available from Indiejazz.com. He has a duo with Ches Smith, this brilliant drummer who still plays a lot with Carla, the duo's called Good for Cows and they have three CDs, a bass and drums duo, it's fantastic. He's currently playing guitar in a band called Seven Year Rabbit Cycle, it's ex-members of Deer Hoof, and he has his own group with Carla Kihlstedt on violin, from Tin Hat Trio, and players from Sleepytime Gorilla Museum. Ches and Devin are like therhythm section in the Bay Area, they're everywhere now."

Destroy All Nels Cline

Like many writers, Cline does most of his composing in preparation for specific projects, and with the specific musicians in mind. Possibly his most ambitious project to date is Destroy All Nels Cline, with Woodward Lee Aplanalp, Cline, and G.E. Stinson on electric guitars, Carla Bozulich on electric guitar and sampling keyboard, Bob Mair, from his first trio, on electric bass and guitar, Alex Cline on drums and percussion and, on certain tracks, Wayne Peet on clarinet and "fake" mellotron and Zeena Parkins on electric harp. " Destroy All Nels Cline was never conceived as a working band," says Cline, "even though we did do, I think, four gigs. Two of them were opening for rock bands, one was Sonic Youth the other was Fugazi. It didn't scare the Sonic Youth audience, people loved it, that's really the best audience I could ever play for, it's the best audience I could ever imagine, but Fugazi's audience was quite divided.Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.