Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Two Ways of Bookending John Coltrane

Two Ways of Bookending John Coltrane

Arcimboldo was a 16th century Italian painter with the skill to paint a glowing lemon as a grotesquely dissociated ghost of itself. In Coltrane: The Story Of A Sound, Ben Ratliff commits no less an act against Coltrane, while in The John Coltrane Reference, Lewis Porter and his international team of Coltrane scholars shed a robust and healthy light on their subject.

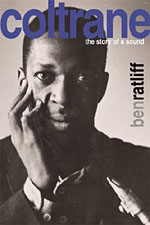

We'll look at Ratliff's offering first.... Coltrane: The Story Of A Sound

Coltrane: The Story Of A Sound

Ben Ratliff

Hardcover; 250 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0-374-12606-3

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

2007

Ratliff certainly seems to begin his work with a worthwhile premise. He writes in his introduction, "This is not a book about Coltrane's life, but the story of his work." One might question how effectively Coltrane's life can or ought to be factored out of the analysis of his music, but the author's intended focus appears valuable. Yet, in spite of this stated focus, both facts and speculations about Coltrane's life appear in every one of the book's twelve chapters.

Structurally, the book is divided into two parts. The first seven chapters are Ratliff's overview of the importance of Coltrane's concerts, recordings and bands, occasionally punctuated with biographical tidbits. The remaining five chapters explore Coltrane's ongoing influence upon musicians, critics, and music lovers.

To be fair to the author, it pays carefully to read the following sentence from Ratliff's introduction in which he explicates his book's subtitle: "I mean 'sound' as it has long functioned among jazz players as a mystical term of art: as in, every musician finally needs a sound, a full and sensible embodiment of his artistic personality, such that it can be heard, at best, in a single note."

If this sentence appears lucid and helpful in broadening your understanding of Coltrane's music, please ignore the rest of this review and read this book with pleasure. I have read this sentence repeatedly—and could summarize my comprehension as follows: "Every jazz musician has a unique sound. Their music is best enjoyed when their notes are revealingly audible." And what does "mystical" mean in this context? Musicians develop a sound with their literal fingers, lungs, heart and brain fully engaged. Is that "mystical?" Perhaps. What matters is that Ratliff confuses his own unproven assumptions and grand speculations about jazz in general, and Coltrane in particular, with reality.

Here is another ex-cathedra offering: "The best jazz playing (and the best jazz criticism) has made room for the notion that this music makes its own meaning without the superimposition of any particular intellectual one, that it will advance by slow degrees, and that it will go around and around in further understanding and refinement of itself, eating its own tail."

This is a fascinating idea, rendered literary and high-brow by the sly reference to the snake eating its own tail, ouroboros, a favorite archetype of the psychoanalyst Carl Jung. Unfortunately, the sentence is also pompous, pretentious, and devoid of clear meaning. Ratliff never defines what he means by "the best" jazz playing and jazz criticism, unless we can assume he is tooting his own horn in his book. The key to the vagueness in this, and many other statements, circles on the abstract opening subject. The author might have written, "I've always thought the best jazz playing and criticism was free of extramusical associations..." But Ratliff likes to let "jazz" be the subject of high-sounding utterances that are nothing more or less than his undefended opinions.

As you read through pages of half-truths, absurdly broad generalizations, amazing omissions and spacey speculations (don't miss the Coltrane on LSD conjecture on page 155), as well as pointless literary and pop culture allusions, one asks oneself: why does Ratliff maintain his authoritative tone? On page 11 of this book—which is "not about Coltrane's life" remember—Coltrane is classified, by virtue of a horrible sounding 1951 bootleg recording, as fitting "an American romantic type" that includes, and I'm not making this up, "Johnny Cash, Clint Eastwood, Waylon Jennings, Walt Whitman, and Gertrude Stein."

This giddy hyperbole seems worthy of a college freshman paper written under the influence of dope—and is insulting from the jazz critic for the New York Times. And lest you think this is merely a mild excess, the poet Robert Lowell is dragged into Ratliff's Coltrane's analysis twice, along with Susan Sontag, Herman Melville, and D.H. Lawrence—all for unclear reasons, unless you think Coltrane was performing variations on Lowell's theory of "the monotony of the sublime."

This preposterous literary razzle-dazzle might be overlooked if not for what Ratliff overlooked. Soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, who actually helped Coltrane learn how to play soprano saxophone, is not credited for doing so. In fact, Lacy's identity is never even explained at all. Reed player Anthony Braxton is encapsulated as "less heroic" than Coltrane. You have to read Braxton's comments in The John Coltrane Reference to understand the seriousness of Ratliff's flip reduction of Braxton's tie to Coltrane.

This book is a shamefully superficial and snobby portrait of Coltrane and his sound. The John Coltrane Reference

The John Coltrane Reference

Chris DeVito, Yasuhiro Fujioka, Wolf Schmaler, David Wild

Edited by Lewis Porter

Hardcover; 848 pages

ISBN-13: 978-0-415-97755-5

Routledge

2007

And now for something completely different....Coltrane fans have been blessed for a decade by the countless insights backed with sharp musical analysis offered by Lewis Porter in John Coltrane: His Life And Music (University of Michigan Press, 1998). Porter combines meticulous scholarship with an eye for telling details, the revealing and necessary details about Coltrane's life and music that constantly open up new perspectives. There is no gratuitous quoting of literary figures irrelevant to Coltrane, or bizarre factoids (the attendance at a New York Museum of Modern Art Chagall show the year Coltrane's classic quartet recorded at The Village Vanguard (see page 69 in Ratliff).

Porter assembled an international team of Coltrane researchers who, with extraordinary care, created a day-by-day chronology from birth to death, an exhaustive concert schedule and discography, a list of all film and television appearances, and close to 400 album covers and photos. Surprisingly, it is an engaging read, as few discographies ever are. Some of the richest treasures in this treasure of a book are the reprinted reviews of Coltrane performances and recordings covering his career. They range from racial and political sermons to intellectually rigorous musicological analysis. They quite meaningfully supplement the reviews reprinted in Woideck's The John Coltrane Companion. None are as ponderous and theory-laden as Ratliff's writing.

The intensity and accuracy of the scholarship in this monumental effort cannot be praised enough. To reveal the difference between an approach like Porter and his team's versus Ratliff's, both books repeat Coltrane's response at a Tokyo press conference to a reporter's question about where Coltrane would like to be in the future. Coltrane responded, "I would like to be a saint."

Ratliff quotes this as a seriously summative utterance to ponder about Coltrane's vision of his spiritually-infused music and career circa 1966. Here, by contrast, is the explanation of the quote offered on page 778 of The John Coltrane Reference:

"Near the end, he is asked what he would like to be in the next ten or twenty years, and he replies, 'I would like to be a saint.' This oft-quoted comment has been greatly misunderstood. On the recording he and Alice (Coltrane) both laugh, and it is clear he is joking."

To give Coltrane his due in book form is to be as painstaking in researching as Coltrane was in practicing. This book honors its subject through such exercise of care.

< Previous

Change of Scenery

Next >

Refreshingly Addictive

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.