Home » Jazz Articles » Profile » Coco Zhao: Dream Situation

Coco Zhao: Dream Situation

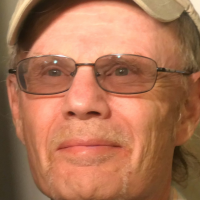

I once mentioned to a friend that catching a singer who looks like he or she is a year or two away from imminent demise, in other words at his or her performing best, is often a matter of serendipity — being at the right venue at the right time. By that standard, Coco Zhao, who goes by the name of Coco—a marketing strategy that will not help his career — whom I caught during the 2006 version of the Montreal Jazz Festival, sounds and looks like the stuff of immortality: a glistening shock of black hair, cheeks spun out of peach fuzz, a smile wider than the sum of the world's evil, all of it confidently carried on nimble legs fitted into pants with enough crotch-drop to shade the ankles. As for the music, which boldly and credibly fuses elements from both the pentatonic and diatonic scales (Chinese music and jazz), it presents a number of challenges from which careers either break down or break out.

I once mentioned to a friend that catching a singer who looks like he or she is a year or two away from imminent demise, in other words at his or her performing best, is often a matter of serendipity — being at the right venue at the right time. By that standard, Coco Zhao, who goes by the name of Coco—a marketing strategy that will not help his career — whom I caught during the 2006 version of the Montreal Jazz Festival, sounds and looks like the stuff of immortality: a glistening shock of black hair, cheeks spun out of peach fuzz, a smile wider than the sum of the world's evil, all of it confidently carried on nimble legs fitted into pants with enough crotch-drop to shade the ankles. As for the music, which boldly and credibly fuses elements from both the pentatonic and diatonic scales (Chinese music and jazz), it presents a number of challenges from which careers either break down or break out. The test and reputation of any nation's art and culture often depend on their ability to win acceptance in other lands. Unlike its gastronomy, Chinese or pentatonic composition has not fared well outside its borders compared to universally embraced Western, diatonic music—and with good reason. As a physical, tonal fact, the former, in the key of C, is comprised of only the five black keys on the piano; it cannot and does not provide the permutational diversity and precision inherent in the diatonic scale which, in C, is comprised of the seven white and five black keys. Given the choice, most composers and listeners gravitate to the more interval-rich diatonic mode.

Through the force of his sincerity and productive imagination, Coco's east-west fusion recommends itself, in part, because he refuses to restrict himself to his pentatonic roots and demonstrates that, whether in convergence or opposition, both the pentatonic and diatonic scales are musically compatible. If during the past twenty years, fusion has degenerated into self-parody—where the mixing of unlike genres, regardless of the incompatibility of their elements, has become its own justification, resulting in a music that at its best is mannered, at its worst, soporific—the arrival of Coco heralds a much needed resuscitation of the original impulse that inspired the genre's spectacular emergence (keyboardists Joe Zawinul and Chick Corea; bassists Jaco Pastorius and Stanley Clarke).

If the first significant example of modern fusion dates back to Bob Dylan's synthesis of folk, rock and electric in the mid-1960s, it wasn't until rock and jazz combined that fusion gained currency as a genre, which quickly grew to include the mixing of music from unlike cultures, culminating in the great and still unsurpassed experiments of guitarist John McLaughlin and the Shakti albums. Like McLaughlin, Coco seamlessly fuses distinct music and languages and, despite his westward bent, leaves enough of the pentatonic in play to satisfy the eastern ear, which, in consideration of China's 1.4 billion population and chart-busting marketing prospects, won't offend Effendi, Coco's Montreal label.

Be that as it may, Coco croons mostly in Chinese as if apologizing for his diatonic trespassing. He sings with measured passion and humble restraint and intuitively understands that the freedoms provided by jazz are only as meaningful as the obstacles imposed on an ever expanding range of musical choices. Make no mistake about it: we're not talking about pentatonic-glossed dinner # 3 music here. Coco's kid-glove, mellifluous vocalese, supported by a group of sympathetic musicians—which include Huang Jianyi on piano and Peng Fei on violin—allows feeling, and not narrow tradition or loyalty, to choose the right sequence of notes and textures. And if we concede that Coco is still at the formative stage of his career, it is no small accomplishment that his first recording raises more questions and expectations than enduring results. After all, he is implicitly competing with the best of fusion, which may be the only way to arrive at a new way of thinking about the possibilities of music.

Be that as it may, Coco croons mostly in Chinese as if apologizing for his diatonic trespassing. He sings with measured passion and humble restraint and intuitively understands that the freedoms provided by jazz are only as meaningful as the obstacles imposed on an ever expanding range of musical choices. Make no mistake about it: we're not talking about pentatonic-glossed dinner # 3 music here. Coco's kid-glove, mellifluous vocalese, supported by a group of sympathetic musicians—which include Huang Jianyi on piano and Peng Fei on violin—allows feeling, and not narrow tradition or loyalty, to choose the right sequence of notes and textures. And if we concede that Coco is still at the formative stage of his career, it is no small accomplishment that his first recording raises more questions and expectations than enduring results. After all, he is implicitly competing with the best of fusion, which may be the only way to arrive at a new way of thinking about the possibilities of music.

Coco's debut CD, Dream Situation (Effendi, 2006), which features interpretations of mostly Chinese originals, is underscored by its sense of mission and purposeful coloring and contouring in the shaping of a highly original music. Depending on mood and moment, the players can draw from either the jazz idiom or the pentatonic songbook. Whether or not this east-west meld has enough centripetal gravitas to become the seed and centre of a new, self-generating musical constellation remains to be heard.

Photo Credit

Li Jun

Tags

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.