Here are my favorite quotes from interviews posted between July and September 2009:

Clarinetist Buddy DeFranco on his big bands of 1949-1951: “I never should have put them together. It had nothing to do with the music, which I think still holds up. It cost me a lot of money but went nowhere in terms of the big picture. I should have listened to [agent] Willard Alexander. He told me, 'Big bands are folding. Let me get you a small group, and we'll make money.' “

Buddy DeFranco on the beating he and Dodo Marmarosa suffered at the hands of sailors in 1943: “Just weeks earlier, at the end of May [1943], there had been riots in L.A. between servicemen and kids in Zoot Suits. If you wore a Zoot Suit, you were considered a wise guy and fair game. In Philadelphia, while Dodo [pictured] and I were waiting for a subway, sailors came across the tracks, hopping the third rail, catching us by surprise. When they came up onto the platform, one sailor said, 'Take those Zoot Suits off.' We tried to tell them they were band uniforms and that we were in Gene Krupa's band. But before we could explain, they started to let us have it. Dodo got the worst of it. I got a fractured nose and ribs. Dodo got hit so hard he hit his head on the cement and was knocked unconscious. Dodo was always a little off but he seemed different after that beating."

Buddy DeFranco on his 1945 Opus One solo with Tommy Dorsey: “I didn't like my solos on there. When the single came out, it became a hit. So going forward Tommy [Dorsey] insisted I play my two solos just the way I had on the record, note for note, over and over again. Sometimes five or six times a day."

Singer Jon Hendricks: “Art Tatum lived five houses from ours in Toledo, Ohio. When I started to sing as a kid, Art accompanied me on the radio. Soon he began calling me for gigs. Can you imagine? Art Tatum calling me to sing with him? When I was 9 years old, I was known as Little Johnny Hendricks and sang at the Rivoli Theater in Toledo. Art was 21 years old."

Jon Hendricks on singing with Charlie Parker: “At a club in New York, Bird announced, 'In Toledo, Ohio, an amazing young cat jumped up on stage and scatted. He happens to be here tonight. Come up, Jon.' Then Roy Haynes said real loud, 'No, no, we don't want no singers, Bird.' Parker said, 'Roy, cool it and sit down and play the drums.' I got up with them and sang three numbers, and the house went wild."

Jon Hendricks on singing Don't Be Scared with King Pleasure in 1954: King Pleasure said, “You're a writer. Write your lyrics." So I did. That's why when you listen to the recording, his words sound like a father talking to his son and I'm responding. I came up with that concept. Quincy [Jones] arranged that session."

Jon Hendricks on Lambert, Hendricks and Ross' Sing a Song of Basie:“We came in and re-recorded everything at night, the way it should have been done in the first place. And when we heard the master the next time around, all of us sat down and cried like babies. You could hear instantly how good it was. And to this minute, till right now, I can truthfully say that it's the best vocal album I have ever heard in my entire life."

Herb Snitzer on his famous photo of Louis Armstrong: “Louis isn't angry here. He's hot. We all were. The image was taken in July 1960, aboard Louis' band bus heading to a concert in Tanglewood, Mass. The bus--like all buses back then--wasn't air-conditioned. The seats were bolt upright. And there was no bathroom on board. Louis was wearing shorts, rolled down socks, sandals and an open shirt. We were all dressed light. When I think back on this photo, like many of the photos I took then, it was the result of my naivete. If I had thought about what I was doing and who Louis was, I would have been too intimidated to get that close to him." [Photo by Herb Snitzer. Herb Snitzer/All rights reserved. Photo used here with the artist's permission.]

Saxophonist Hal McKusick on trombonist Bill Harris: “Perhaps my favorite Bill Harris [pictured] story took place at Birdland in Miami, when the New York club had a Florida outpost. Toward the end of the band's stay at the club, Bill loosened his pants' belt. Then he had the band play Artistry in Rhythm, Stan Kenton's theme. As he conducted dramatically, like Kenton, he sucked in his stomach, turned to the audience and let his pants drop to the floor. The club manager let the band go that night. Bill may have looked like a serious guy, but he was as wild as anyone back then."

Pianist Dick Katz on clarinetist Tony Scott: “He was a mercurial egomaniac. Extremely talented but headstrong. He was like a salesman who oversold himself. He was multitalented. But he'd get an audience in palm of his hand and he'd keep on going and lose them."

Dick Katz on recording Body and Soul on Benny Carter's Further Definitions: “[Years earlier] Teddy Wilson had showed me some chord changes for the second bridge to Body and Soul. I passed them on to Hawk at the session, and he used them in his solo. It's an altered-chord sequence."

Saxophonist Med Flory on Terry Gibbs' Dream Band: “Terry came to [Los Angeles], heard my group and thought we could make it bigger. So all those charts I had went over to Terry. I don't lend out charts any more. I don't blame Terry. He had landed the gig. But he heard my band and that's what got him going with that."

Med Flory on his preference for Al Cohn over Zoot Sims: “Zoot wasn't in the same category as Al. Zoot was a good swing-time player. But Al was otherworldly... Al's writing and playing were above most everyone else."

Med Flory on how the idea for Supersax originated: “Around October 1956, [saxophonists] Joe Maini, Charlie Kennedy, Richie Kamuca and Bill Hood came by my house [in Los Angeles]. Joe Maini had a record player and a bunch of Parker records. I gave him $50 for the player and the discs. Then I started transcribing a few things of Bird's that were in the stack, like Star Eyes, Chasin' the Bird and Just Friends. I wrote out those three charts from the records. Then one night in 1957 we were playing the Crescendo with the Dave Pell Octet. Buddy Clark was playing bass. Afterward, we all went over to my pad. Buddy said, “Play that thing with the saxes--Just Friends.“ When we were done, Dave said, 'Boy wouldn't it be great to have a whole book of those things.' Buddy said he'd take a shot. The trick was to keep everything within an octave. The line is everything. What Bird played is the thing. You don't have to dress it up with voicings or anything."

Big Jay McNeely on why he became an r&b tenor saxophonist: “I started out playing jazz but I didn't have a perfect ear, like Sonny Criss did. Guys like Sonny could pick up their horn and play anything. They heard things once, and they could go off on it. Also, back then, there were so many players, you had to be different on your horn to stand out. Eventually it was a money issue."

Denny Zeitlin on his jazz piano style: “When I play, I'm always searching for the joyful experience I first had as a child playing music. In that kind of ecstatic space, I lose the positional state of myself. I'm not observing consciously what I'm doing. It's pure intention, pure music."

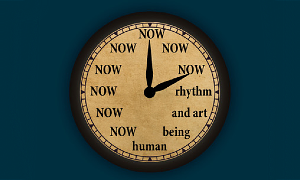

Denny Zeitlin on creating art as a jazz musician: “You must bring together all of the structure you've learned: your having practiced thousands of hours learning technique and craft. It's all of those formal things plus your philosophy about aesthetics--your sense of form and what you personally think sounds beautiful. All of that comes from the typically 'Western'-type traditions we've grown up with. But true art also has components associated with so-called 'Eastern' traditions that focus on merging with one's experience--truly being in the moment."

Bill Evans' lover Laurie Verchomin on Evans' body: “When I met Bill, he was an an intravenous cocaine user. This created a chronic level of infection, which was adding to the general stress of his health. Tracks from his earlier heroin addiction had healed over, and his skin was in a kind of petrified state."

Laurie Verchomin on the toll that Bill Evans' drug use took on his health: “Bill rarely slept the entire time I knew him [in 1979-1980]. When you're consuming cocaine the way Bill was, he would be in different states of exhaustion and never truly rested. He never slept."

Laurie Verchomin on Helen Keane, Bill Evans' manager and producer: “Helen couldn't handle the stress of where Bill was headed. Bill didn't need or want the extra financial stress either. Toward the end, she didn't want to be in close personal contact with him any more."

Laurie Verchomin on Bill Evans and the start of his heroin addiction in the 1950s: “Bill didn't talk about how he got hooked. But he did say his addiction had started before joining the Miles Davis Sextet in 1958. Bill said he came to heroin on his own. It was around the time he joined Miles, but it wasn't through Miles."

Laurie Verchomin on Bill Evans' little known investment: “Bill [in 1979 and 1980] owned a racehorse with Jack Rollins, the producer of Woody Allen's films. The horse's name was Annie Hall. It was a trotter--one of those harness-racing horses that pull a two-wheeled cart."

Laurie Verchomin on the day of Bill Evans' death: “If you consider the event spiritually, it was the end of a journey I chose to take with him. When we met, it was as though it was the beginning of a song. When Bill died, it was like a big orchestral crescendo. I remember the clouds in the sky that day [September 15, 1980], the bright red color of his blood--the entire day was like a Michelangelo painting." [Photo by Jaap van de Klomp]

Roy Phillippe on arranging Jimmy Forrest's Bag of Dreams for Count Basie: “When I finished the score I mailed it to Jimmy, hoping it was good enough. About a month later I received a letter from Jimmy. Basie really liked the chart, he said, and the band was playing it every night. He also asked me if I would be interested in arranging his most famous piece, Night Train, which was a big hit in 1952. Of course I agreed. Later, he wrote to say that Basie liked that one, too. I wasn't paid for either arrangement, but it didn't matter. Arranging for Jimmy and Basie was an honor."

Bassist Howard Rumsey on Stan Kenton'sArtistry in Rhythm: “Stan wrote it originally as an arrangement to rehearse the reeds. It wasn't meant to be a featured arrangement, but eventually he worked it into the book. It came to him through a classical piece."

Howard Rumsey on the musicians who played at the Lighthouse: “Some migrated out West, but most left the big bands that settled here in the winter, like Woody [Herman], Les Brown, Stan Kenton, Charlie Barnet and others. The musicians could work casual with me at the Lighthouse, and the union would allow it. The union wouldn't let them work in the L.A. studios for six months. That's why they worked the Lighthouse at first. The Lighthouse was a true jazz gig. [Pictured: Shorty Rogers and Howard at the Lighthouse]

Howard Rumsey on the West Coast jazz sound: “It's the music of happy--in a hurry... The gimmick was not to put too much emphasis on the after-beat. [Gerry] Mulligan had such a great sound. So did Shorty [Rogers]. They had to keep the action going. So they kept talking to each other harmonically with lines."

Howard Rumsey on the musicians who were most responsible for the West Coast jazz sound: “It was a combination of Gerry Mulligan and Shorty Rogers. They changed the whole scene. They get the big medals."

Saxophonist Dave Pell on Don Fagerquist: “When Don would start a solo, he knew exactly where he was going to end up. He'd work it out in his head in advance. Then he'd play right up to that ending he had in mind and always wrap his solo on the note he chose. That's why his solos always sounded planned out."

Singer-pianist Meredith d'Ambrosio on a 1965 breakfast with John Coltrane in Boston: “After his gig, Coltrane, Robin [Hemingway] and I went to Ken's, a coffee shop in Copley Square, for breakfast. We sat there till 3 a.m. talking. I was told later that John never laughed or smiled. But during our time at Ken's, he was laughing and enjoying himself the entire time. He asked me to sing something for him, and I did. After I finished singing at the table, he was so moved he asked me to come with him to Japan and sing with the group. But [my daughter] Cyd was just four years old, and I was living with my parents after escaping my marriage. I explained why I couldn't go with him. John understood."

Meredith d'Ambrosio on her recording break in the late 1970s: “Ron Della Chiesa invited me to come on his WGBH-FM radio show, Music America, to play the tape I had made. Johnny Hartman was also being interviewed by Ron that day. When the tape played, it sounded like an album. When Johnny heard it, he couldn't believe it wasn't. Johnny insisted on taking the tape to New York to play for a record producer he knew. Johnny thought it should be an album. I was surprised he was so kind to me. I was a fan of his."

Donna Wilcox, a Washington, D.C., summer-school volunteer who in 1965 who convinced Dizzy Gillespie and his band to play for the students: “After the [early morning] concert, the students presented the musicians with a letter of thanks. Then Dizzy came off the stage, and the students gathered around to look close at the famous tilted horn... Dizzy was a most generous, talented, funny man. I will never forget him, his kindness or his music." [Photo by Donna Wilcox]

Pianist Don Friedman on the origin of Scott LaFaro's Gloria's Step: “Scotty soon moved down to the Lower East Side with Gloria, his girlfriend. They never married. Gloria was a lovely girl and a dancer. She and Scotty remained together until his death in early July 1961. The song's name originated because he knew the sound of Gloria's footsteps when she came up the stairs to their apartment, not because she was a dancer."

Saxophonist Med Flory on trumpeter Dick Collins: “Dick's nickname was Bix. Not because he could play like Beiderbecke but because he was a country boy who could play jazz. He didn't do anything outrageous. He just played great. He was the real McCoy. And a nice guy. No one ever said anything bad about Dick. His sound had a real pretty punch."

Trumpeter Al Stewart on the Benny Goodman-Louis Armstrong ego rift of 1953: “Benny said, 'Jesus Christ, let's get this goddamn show on the road.' Louis walked over to the trombone riser and sat down with his elbows on his knees and his chin in his hand. Glancing up at Benny, he said, 'Man, I been trying to get this show on the road now for two days now. But it seem like some asshole done snuck in here somewhere.' “

Al Stewart on hanging out backstage with Louis Armstrong in 1953: “We were sitting there talking when Joe Bushkin, who was playing piano in Louis' band, stuck his head in and shouted, 'Hey Pops, what are you doing?' Louis said, 'I'm doing my autobiography.' Joe said, 'Yeah? You almost done?' Louis said, 'I've got 600 pages done, and I'm only up to 1929.' “

Al Stewart recalling Louis Armstrong's cool temperament: “On Louis' band bus, Charlie Shavers said to Louis, 'Hey Pops, look at the way this guy's driving. He's going to kill us.' Louis looked up at Charlie slowly and calmly said, 'Sure make your spine tingle, don't he?' Louis always had the right answer for everything. He could cut right through it all."

Early rock pioneer Big Jay McNeely on why he hasn't been inducted yet into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame: “I don't know. I guess the people who make those decisions don't realize I'm still around."

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.