Glaser had enormous admiration for Louis' playing and spirit. But he also saw a gold mine in disrepair. Louis, in turn, respected Glaser's no-nonsense business sense. But his decision to call Glaser also came from a mix of vulnerability, career fear and pragmatism. So in 1935, Louis and Glaser struck a deal. Glaser would manage Louis--hauling in jobs, covering expenses and taxes, and paying Louis $1,000 a week. This grand was net, in a year when the top tax rate was 64%. To make the merger official, the pair merely shook on it. They never signed a formal contract. [Photo: Joe Glaser and Louis Armstrong in 1965 by John Loengard for Life]

In truth, the deal wasn't a pact between equals. Glaser held the power in the relationship from the start, and Louis would always remain hat-in-hand with Glaser. In the 1930s (and beyond), Louis obediently did whatever his manager thought was best, confident that what was good for Glaser would be good for him. It certainly was a gamble, even in tough times. But Louis' goal was to never again face another mid-1930s meltdown. From the start, Louis shrugged off the lopsided dynamics, since all he really wanted to do was play and record.

And record he did. In 1935 Glaser landed Louis a deal with Decca Records. The newly launched label was founded a year earlier by Jack Kapp, a former executive with Columbia's Brunswick subsidiary. The entire output during the 11 years that would follow--166 tracks--has just been issued by Mosaic Records on The Complete Louis Armstrong Decca Sessions (1935-1946). More on the box in a minute.

Kapp's strategy at Decca was simple. He insisted that artists like Bing Crosby, Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington and Louis record songs that were big on melody and rich in soul. This marketing brainstorm today sounds absurdly simple and obvious. But back in the mid-1930s, it was a radical concept for popular music. As part of the record deal, Glaser let Kapp produce Louis any way he wished. Which wasn't always a good thing, at least not to today's ear. Kapp early on positioned Louis as a novelty act, a bluesy talk-singer-player whose closest artistic rival during this period was probably Fats Waller. But the vast majority of the Decca recordings remain remarkable evidence of a rising star and entertainer being re-born during the most important 11 years in jazz history.

By viewing this period as a campaign by Glaser and Kapp to turn Louis into a mega star, you are able to better understand why Louis recorded so many tracks mugging for the microphone. More important, you get to hear Louis' development from a Kapp experiment to a dominant and unrivaled artist of stunning talent and achievement. Throughout the late 1930s, Louis' records continued to amaze, and by the early 1940s, his Decca discs were single-handedly converting saloon jazz into mainstream popular music. Louis' style and spirit also became a populist model, heavily influencing many other artists recording for Decca and other labels.

The Mosaic box starts with Louis fronting his own orchestra recording I'm in the Mood for Love (1935). What you hear is a fabulous trumpet dancing around the melody followed by a trademark Louis vocal. As the 1930s matured, and swing bands became more dominant with the rise of national radio, big bands and records, Louis' efforts become more ambitious without losing their earthy luster. They also become more homey and familiar as Louis developed his storyteller niche.

This box is loaded with gems, like On the Sunny Side of the Street (1937), featuring an especially gravel-voiced Louis. And there are some oddities, like Hawaiian Hospitality (1937), complete with ukulele and steel guitar. Or the ponderous Old Testament discs of 1938 with the Decca Mixed Chorus directed by Lyn Murray. But all in all, the 1935-1938 period is jammed with flawless foot-tappers and spirit sparklers.

A turning point in Louis' Decca years is Struttin' with Some Barbecue (1938), which focuses less on Louis' gimmicky vocals and more on musicianship and swing. It also has to be one of the happiest recordings of the period. And on Johnny Burke and James Monaco's Trumpet Player's Lament, Louis' playing is the essence of joy. Other winners to follow include Rocking Chair and Lazy Bones (1939), recorded with trombonist and soul mate Jack Teagarden. In fact, part of Kapp's genius was to team Louis early on with other Decca artists, many of whom were white. Tandem tracks here include dates with Glen Gray, Jimmy Dorsey and Bob Haggart. Louis clearly was Kapp's secret weapon in helping to blur racial lines in popular music and the entertainment industry. It was in Kapp's best financial interest, of course, that such lines disappear.

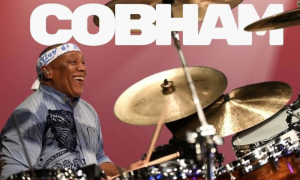

Perhaps my favorite tracks in the box appear at the end of the sixth disc and fill the entire seventh. This is the period from 1941 through 1946, which was interrupted by the musicians' ban that for Decca lasted from 1942-1943. The arrangements along with Louis' playing jump yet another notch. Dig Hey Lawdy Mama, a blues with a seductively tricky melody line and lyrics. Or the more modern pieces by arrangers Sy Oliver [pictured] and Joe Garland like Leap Frog, Coquette and Among My Souvenirs.

To be completely honest, I initially had trouble with this box. Upon my first listen, the material felt heavy on Louis' self-parodying. But after a conversation with Terry Teachout, whose biography Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) is due out December 2d, I was able to put the period in perspective. Once you know the back-story and are aware of the dramatic struggles Louis faced, this music makes perfect sense and becomes much more significant. Ultimately, what you have here is a box that documents the pivotal evolution of jazz's greatest artist, from trumpet star on the ropes to a champion swinger and entertainer. Shrewdly, Louis put himself in the hands of Glaser and Kapp, figuring that his musicianship and charm would supersede any bad business decisions. And he was right. As these recordings clearly demonstrate, Louis quickly became his own man and jazz's greatest pioneer. In the process, he turned what had been considered ethnic entertainment into American popular music, seducing everyone along the way. Now that's quite an 11-year journey.

JazzWax tracks: The Complete Louis Armstrong Decca Sessions (1935-1946) is truly a must. Not only does it cover a critical period in Louis' career and the simultaneous rise of swing, the recordings capture an earthy era of hardship and hope. The can-do spirit bundled into Louis' playing not only is remarkable but also timely given today's economic uncertainty.

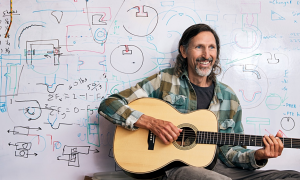

Hats off to the box's producer, Scott Wenzel, who did a remarkable job of pulling together the recordings and rare alternates from metal parts. The detail-rich liner notes are by Dan Morgenstern [pictured] of Rutgers University's Institute of Jazz Studies. Like all of Dan's writings, these notes are as cozy and as friendly as a pair of slippers. You'll find the box here.

JazzWax clip: Here's a taste of what this music sounds like along with fine analysis by Dan Morgenstern...

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.