Back on December 2, I posted a 2.5-minute YouTube clip from a documentary unfamiliar to me called The Legend of Bop City. This particular Bop City wasn't the famous one in New York on the second floor of the Brill Building on 49th Street and Broadway. This one was in San Francisco and had been a hotbed of modern jazz in the 1950s and early '60s.

After a little research, I discovered that the documentary's director was Carol P. Chamberland. But there was no bio, no Wiki entry, zilch. Who was she—or he? Was Carol still around? Why hadn't the documentary been circulated or made available on DVD or streaming? I began an in-depth internet search.

A Carol Chamberland with the middle initial “P" popped up in a directory in the Southwest. I took a chance and called the number and connected with an answering machine. I left a message. Carol called me back. She was indeed the director of The Legend of Bop City.

Carol and I became fast friends. I told her about JazzWax, that I loved the clip and wondered if I could share her entire documentary with readers. We figured out the best way to do this. Tomorrow, you will have a rare opportunity to see The Legend of Bop City. The hour-long video will open the JazzWax Film Festival, which will run from December 27 to January 7.

The documentary will be available for free with a link and a password that I will provide. You can watch it multiple times and share it with friends. You'll have free access until Sunday at midnight, when it no longer will be available.

Today, I thought it best you meet Carol through an interview I conducted with her by email, how her documentary came to be and why it isn't available commercially.

Here's Carol:

JazzWax: Carol, where did you grow up?

Carol P. Chamberland: My ancestors came from France to Canada in 1663. My parents were both French-speaking natives of Quebec City and emigrated to the U.S. in 1947. I was born in America in 1948. They knew little about American culture and nothing about the music.

JW: When did you first hear jazz?

CPC: I was bitten by the jazz bug at 14, while on a cross-country camping trip with my father and sister. We were visiting New Orleans and stopped in at Preservation Hall. I was taken by the ambiance, the old-timers on the bandstand and especially the music. So lively! So swinging! Dad had to drag me away that night. Once back home, I inched into jazz listening to albums by Ramsey Lewis and Dave Brubeck. While my parents were grooving to Perry Como and Pat Boone, I was devoted to Ray Charles. The heck with April Love. Hit the Road, Jack! [Photo above of Preservation Hall in New Orleans, courtesy of Preservation Hall]

JW: Did you study art and film in college?

CPC: After high school, I attended the Hartford Art School for four years, majoring in painting. The curriculum included a class in photography, which was daring since it wasn’t considered formal art back in the 1960s. Later, I completed my undergraduate studies at Arizona State, earning a BFA in painting with a minor in computer science.

JW: Computer science as a Plan B?

CPC: Sort of. In 1978, no other art students were also taking business and engineering classes in computer programming, but by then I had become practical about earning a living. A few years later, while working as a software consultant in San Francisco’s Bay Area, I earned an MA and MFA in conceptual design—art and technology—from San Francisco State. It was the only U.S. graduate program I could find that encouraged artists to use computers.

JW: Had you made documentary films prior to The Legend of Bop City?

CPC: To be clear, The Legend of Bop City is a video, not a film. The first video I ever made was with my friend and mentor Harris Cohen. He was a retired network-TV cameraman and news editor who owned Magnetic Image, a video production support company.

JW: What was it about?

CPC: In 1988, I was finishing up my MFA thesis—Art in the Fast Lane—which centered on automobiles in art. As an adjunct to my main art piece, a highly modified defunct Austin-Healey, we created a short video about abandoned cars in San Francisco entitled NOPL8S—"no plates." Vanity plates were a big deal in California at the time. This fake license plate was a reference to the abandoned cars scattered across the city streets.

JW: How did you learn about video production?

CPC: By working with Harris, a master with professional gear before proceeding on to other productions with my own more humble means. Over the next few years, I created several videos—both mini-docs and artsy stuff—before embarking on the Bop City project in 1993.

JW: Were there specific documentaries that you admired?

CPC: I had no real point of reference. All of this happened during my 25 years of avoiding television, so I didn’t have much in the way of documentary role models. However, in the early days of production on Bop City, I did see Jean Bach's A Great Day in Harlem. That film struck many chords.

JW: When exactly did you hear about Jimbo’s Bop City in San Francisco?

CPC: One night in 1992, I was at a jazz performance at Kimball’s East with Ray Simpson, a friend and fellow jazz fan. Between sets, we decided it would be fun to make a music video/CD together. He would find some musicians and a recording studio, and I would assemble a crew of friends with camcorders. His resulting CD was called The Good Old Days Are Right Now. The title may be corny, but the music was good.

JW: What was on the CD?

CPC: Jazz standards.We brought in Allen Smith on trumpet, Vince Cattolica on clarinet, Larry Vuckovich on piano, Al Obidinski on bass and John Markham on drums. After the recording session, the band, camera crew and Ray all came to my art studio for lunch. I shot brief interviews with the musicians, who had all been on the Bay Area scene for decades. It was then that I first heard about Jimbo’s Bop City.

JW: How so?

CPC: They’d all played there at one time or another. The club, by then, had been shuttered for almost 30 years. From that one day of shooting, I edited a video of the recording session with cutaway snippets of interviews. I called it Barbary Coast Bebop, after the racy Barbary Coast section of San Francisco. A century earlier, tourists had frequented burlesque clubs, and musicians had made a living there.

JW: What happened next?

CPC: A few months after completing the edit of Barbary Coast Bebop, Ray heard about a gathering of musicians at Coffee Dan’s in the Tenderloin District. John “Jimbo" Edwards, proprietor of Bop City, was there with his photo albums of images from the club. Jimbo was 80 and was looking for help identifying the people in his Bop City images. Ray and I joined the scene. When I saw the black-and-white photos from Bop City’s heyday, I was bitten again, just like at Preservation Hall 30 years earlier. On a whim, I invited Jimbo to the upcoming premier screening of Barbary Coast Bebop at my Fillmore Street studio, never expecting him to show up. But he did.

JW: When did you decide to document the club’s history?

CPC: For years, Jimbo had wanted someone to write a book about Bop City. He probably envisioned a glossy coffee-table tome featuring his impressive collection of black-and-white photos. Journalist John Ross had already been researching the topic with Jimbo when I met them both. Having seen my storefront studio space, Jimbo asked about bringing some of the musicians there to discuss his photos. I agreed and spontaneously suggested we videotape the conversations.

JW: One thing led to another?

CPC: Yes, and before long we were making a video and putting together a book. That first day we had Allen Smith, Vince Wallace, Ernie Lewis, Earl Watkins and Pat Nacey, who wasn’t a musician but a devoted Bop City fan back in the day. Jimbo and John Ross were also there, plus a couple of volunteers handling the cameras. We decided that Ray would locate musicians and arrange the interviews and John Ross would write the book and the video script. Before long, we settled into a pattern of one-on-one interviews rather than unruly group discussions.

JW: Did you run into a wall?

CPC: Within a year, each of the volunteers had bailed. On January 1, 1994, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) coordinated a 12-day uprising in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, in protest of the enactment of the North American Free Trade Agreement. John Ross migrated south to Mexico to cover the Zapatistas. We didn’t see him again for five years. So, there we were—just Jimbo and me. By then I had seen and heard enough to know this was a great story, so I overcame my deep disappointment and forged on by myself.

JW: Tough sledding?

CPC: It was hard work, and I had a fulltime day gig as a software consultant. But in some ways, it was easier to go solo. No more compromising, arranging complicated schedules or waiting on others to show up.

JW: How long did the video documentary take to complete?

CPC: The whole project took 5½ years—from 1993 to 1998. Four of those years were spent shooting interviews and the remainder was spent in post-production and final negotiations. With a grant from the California Council for the Humanities, I was able to travel to meet Bop City musicians who had migrated further afield. In Portland, Oregon, I interviewed drummer Dick Berk (a.k.a. “Sputnik’) and vocalist Nancy King. In Los Angeles, I spoke with vibes master Terry Gibbs, trumpeter Clora Bryant, vocalist Ernie Andrews and drummer Roy Porter. In New York, I interviewed saxophonists Frank Foster and Dewey Redman, flutist Jerome Richardson and pianists Richard Wyands and Billy Taylor. Then I went on to Washington, D.C., to interview Patricia Willard, jazz consultant with the Library of Congress and former publicist for Duke Ellington.

JW: All before the Internet.

CPC: Tracking down musicians was a laborious word-of-mouth process then. With my professional background as a database analyst, I kept copious records and arranged the interviews into a logical storyline. At times, I worried that the project would never be completed. Jimbo was in his mid-80s by then, and I wanted him to see the final documentary. He had become like a second father to me.

JW: Jimbo’s Bop City was in a building with an interesting past regarding mobility, yes?

CPC: Yes. The club at 1690 Post Street closed in 1965, 19 years before I arrived in San Francisco. Everyone assumed that the building that housed the club had been demolished during urban renewal, along with so many other Victorian structures in the district. While researching similarly defunct Fillmore clubs, I spent hours in the basement of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, going through their archives of boring real estate photos. In the process, I found a shot of the empty Bop City building dated after the mass destruction of the neighborhood. Which was bizarre. The building in which the club was housed had been left standing while many others in the area had been plowed down.

JW: Wow, that is amazing—and strange.

CPC: Following this lead, I located the actual building in San Francisco and was able to prove that it had been uprooted and transported a block down the street and around the corner. During that phase of urban renewal, it was not uncommon for a Victorian house in good condition to be jacked up, hoisted onto a giant flatbed truck and trundled slowly in the dead of night to a different location.

JW: That must have been a mind-blower.

CPC: It was. When I found the building, Marcus Books occupied the space, so I was able to enter the noble room where music history had taken place. The city eventually declared it an historic heritage site.

JW: How many interviews did you bank away?

CPC: During my years of shooting, I acquired roughly 50 hours of interviews—for what was we planned would be a one-hour documentary. Definitely overkill, but there was a reason. Pianist Stanley Willis and saxophonist Pony Poindexter were fixtures on the bandstand at Bop City. They popped up in many artist interviews, usually accompanied by a chuckle or flash of pride. Both had died before I began the project, so I never got to meet them. This lent a sense of urgency to my efforts. I wanted to record as many people as I could while they were still with us.

JW: Who were your most important gets?

CPC: Saxophonist John Handy was one of the first interviewees. We subsequently became good friends, and he served as content advisor to the project. Likewise, drummer Earl Watkins was involved from day one. He became another good friend who provided content advice and good cheer during the slow days. Both of these men also arranged introductions to important Los Angeles musicians. John Handy took me to meet fellow saxophonist Teddy Edwards, who gave me a hilarious interview. Behind the scenes, Earl Watkins urged his gruff friend and fellow drummer Roy Porter to be nice to me, which he definitely was. Earl and John opened many doors.

JW: How did all of those hours of interviews translate into tapes?

CPC: I had at least 70 videotapes that ran 60 minutes each. They included interviews, cutaway footage, voice-over narration and music clips. I built a database to log everything: who was on which tape, the date, location and so on. Nowadays, there is software to transcribe interview materials directly from video footage. But back then, I had to type out the whole interview to get a written record. I created another database to log topics and where the clips could be found on which tapes. Yet another database was created to log computer disks containing digitized photos.

JW: That was a ton of work.

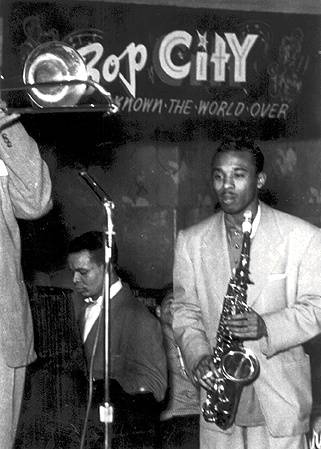

CPC: Shooting interviews was the fun part, but as you can see it was way more work than that. Sometimes I would track down musicians but they refused to participate. Most people were happy to cooperate, though. They seemed pleased that someone valued their memories. [Photo above of tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves and pianist Flip Nunez at Bop City, courtesy of Carol P. Chamberland]

JW: You made the documentary before tape was digital. Was that problematic?

CPC: Yes, videotape was analog when I started the project. Midway through, video went digital, so I learned the new editing software and found an edit suite at an affordable rate. Luckily, my day gig involved writing computer software, so I had a leg up on the transition to digital.

JW: What kept the film from being released commercially?

CPC: Even though I had some grant funding, the total wasn’t enough to cover commercial music rights. Archival footage from KQED-TV was licensed to me for educational purposes at no cost. But the music companies wanted full-price rights, with a “most favored nation” clause, meaning one company couldn't cut me a deal. They all had to get the full rate. Sometimes I replaced a song because the rights battle was so ridiculous. I got around the recording rights by using locally performed pieces that I recorded myself and paid a stipend to each of the musicians on the track. Given all of these hurdles, the finished product was never commercially promoted. It has been on public television—KQED—and various film and jazz festivals over the years. Some libraries purchased copies. The music-rights issue kept me from producing any further music videos, though I have enough material in the can for a documentary on bluesmen Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

JW: How much more footage do you have of the film’s artists?

CPC: Some 50 hours of interviews. If you do the math, that leaves 49 hours of unused material. The video was released in 1998 and has developed a low-key life of its own. But those remaining tapes have nagged at me from their storage location all these many years. Much of the interview material was tangential to Bop City, or it was a different story that was already covered. For example, musicians, employees and jazz fans shared personal memories that shed light on American social conditions of the 1950s and 1960s.

JW: Such as?

CPC: Their commentary covered civil rights, the transition from big bands to rock ‘n’ roll, women’s place in society, the life of traveling musicians, and more. These tales begged to be heard, so I finally wrote a book draft, just as Jimbo had always wanted. It is a poignant view of American history through a jazz lens. Most of the interviewees are now deceased. When Jimbo suffered a fatal heart attack in 2000, he left his precious photo albums to me—so they are available to augment the book if it’s published. It turns out though, that writing the book was the easy part. After two years of trying, I have not found a publisher willing to take it on. Here we go again.

After a little research, I discovered that the documentary's director was Carol P. Chamberland. But there was no bio, no Wiki entry, zilch. Who was she—or he? Was Carol still around? Why hadn't the documentary been circulated or made available on DVD or streaming? I began an in-depth internet search.

A Carol Chamberland with the middle initial “P" popped up in a directory in the Southwest. I took a chance and called the number and connected with an answering machine. I left a message. Carol called me back. She was indeed the director of The Legend of Bop City.

Carol and I became fast friends. I told her about JazzWax, that I loved the clip and wondered if I could share her entire documentary with readers. We figured out the best way to do this. Tomorrow, you will have a rare opportunity to see The Legend of Bop City. The hour-long video will open the JazzWax Film Festival, which will run from December 27 to January 7.

The documentary will be available for free with a link and a password that I will provide. You can watch it multiple times and share it with friends. You'll have free access until Sunday at midnight, when it no longer will be available.

Today, I thought it best you meet Carol through an interview I conducted with her by email, how her documentary came to be and why it isn't available commercially.

Here's Carol:

JazzWax: Carol, where did you grow up?

Carol P. Chamberland: My ancestors came from France to Canada in 1663. My parents were both French-speaking natives of Quebec City and emigrated to the U.S. in 1947. I was born in America in 1948. They knew little about American culture and nothing about the music.

JW: When did you first hear jazz?

CPC: I was bitten by the jazz bug at 14, while on a cross-country camping trip with my father and sister. We were visiting New Orleans and stopped in at Preservation Hall. I was taken by the ambiance, the old-timers on the bandstand and especially the music. So lively! So swinging! Dad had to drag me away that night. Once back home, I inched into jazz listening to albums by Ramsey Lewis and Dave Brubeck. While my parents were grooving to Perry Como and Pat Boone, I was devoted to Ray Charles. The heck with April Love. Hit the Road, Jack! [Photo above of Preservation Hall in New Orleans, courtesy of Preservation Hall]

JW: Did you study art and film in college?

CPC: After high school, I attended the Hartford Art School for four years, majoring in painting. The curriculum included a class in photography, which was daring since it wasn’t considered formal art back in the 1960s. Later, I completed my undergraduate studies at Arizona State, earning a BFA in painting with a minor in computer science.

JW: Computer science as a Plan B?

CPC: Sort of. In 1978, no other art students were also taking business and engineering classes in computer programming, but by then I had become practical about earning a living. A few years later, while working as a software consultant in San Francisco’s Bay Area, I earned an MA and MFA in conceptual design—art and technology—from San Francisco State. It was the only U.S. graduate program I could find that encouraged artists to use computers.

JW: Had you made documentary films prior to The Legend of Bop City?

CPC: To be clear, The Legend of Bop City is a video, not a film. The first video I ever made was with my friend and mentor Harris Cohen. He was a retired network-TV cameraman and news editor who owned Magnetic Image, a video production support company.

JW: What was it about?

CPC: In 1988, I was finishing up my MFA thesis—Art in the Fast Lane—which centered on automobiles in art. As an adjunct to my main art piece, a highly modified defunct Austin-Healey, we created a short video about abandoned cars in San Francisco entitled NOPL8S—"no plates." Vanity plates were a big deal in California at the time. This fake license plate was a reference to the abandoned cars scattered across the city streets.

JW: How did you learn about video production?

CPC: By working with Harris, a master with professional gear before proceeding on to other productions with my own more humble means. Over the next few years, I created several videos—both mini-docs and artsy stuff—before embarking on the Bop City project in 1993.

JW: Were there specific documentaries that you admired?

CPC: I had no real point of reference. All of this happened during my 25 years of avoiding television, so I didn’t have much in the way of documentary role models. However, in the early days of production on Bop City, I did see Jean Bach's A Great Day in Harlem. That film struck many chords.

JW: When exactly did you hear about Jimbo’s Bop City in San Francisco?

CPC: One night in 1992, I was at a jazz performance at Kimball’s East with Ray Simpson, a friend and fellow jazz fan. Between sets, we decided it would be fun to make a music video/CD together. He would find some musicians and a recording studio, and I would assemble a crew of friends with camcorders. His resulting CD was called The Good Old Days Are Right Now. The title may be corny, but the music was good.

JW: What was on the CD?

CPC: Jazz standards.We brought in Allen Smith on trumpet, Vince Cattolica on clarinet, Larry Vuckovich on piano, Al Obidinski on bass and John Markham on drums. After the recording session, the band, camera crew and Ray all came to my art studio for lunch. I shot brief interviews with the musicians, who had all been on the Bay Area scene for decades. It was then that I first heard about Jimbo’s Bop City.

JW: How so?

CPC: They’d all played there at one time or another. The club, by then, had been shuttered for almost 30 years. From that one day of shooting, I edited a video of the recording session with cutaway snippets of interviews. I called it Barbary Coast Bebop, after the racy Barbary Coast section of San Francisco. A century earlier, tourists had frequented burlesque clubs, and musicians had made a living there.

JW: What happened next?

CPC: A few months after completing the edit of Barbary Coast Bebop, Ray heard about a gathering of musicians at Coffee Dan’s in the Tenderloin District. John “Jimbo" Edwards, proprietor of Bop City, was there with his photo albums of images from the club. Jimbo was 80 and was looking for help identifying the people in his Bop City images. Ray and I joined the scene. When I saw the black-and-white photos from Bop City’s heyday, I was bitten again, just like at Preservation Hall 30 years earlier. On a whim, I invited Jimbo to the upcoming premier screening of Barbary Coast Bebop at my Fillmore Street studio, never expecting him to show up. But he did.

JW: When did you decide to document the club’s history?

CPC: For years, Jimbo had wanted someone to write a book about Bop City. He probably envisioned a glossy coffee-table tome featuring his impressive collection of black-and-white photos. Journalist John Ross had already been researching the topic with Jimbo when I met them both. Having seen my storefront studio space, Jimbo asked about bringing some of the musicians there to discuss his photos. I agreed and spontaneously suggested we videotape the conversations.

JW: One thing led to another?

CPC: Yes, and before long we were making a video and putting together a book. That first day we had Allen Smith, Vince Wallace, Ernie Lewis, Earl Watkins and Pat Nacey, who wasn’t a musician but a devoted Bop City fan back in the day. Jimbo and John Ross were also there, plus a couple of volunteers handling the cameras. We decided that Ray would locate musicians and arrange the interviews and John Ross would write the book and the video script. Before long, we settled into a pattern of one-on-one interviews rather than unruly group discussions.

JW: Did you run into a wall?

CPC: Within a year, each of the volunteers had bailed. On January 1, 1994, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) coordinated a 12-day uprising in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, in protest of the enactment of the North American Free Trade Agreement. John Ross migrated south to Mexico to cover the Zapatistas. We didn’t see him again for five years. So, there we were—just Jimbo and me. By then I had seen and heard enough to know this was a great story, so I overcame my deep disappointment and forged on by myself.

JW: Tough sledding?

CPC: It was hard work, and I had a fulltime day gig as a software consultant. But in some ways, it was easier to go solo. No more compromising, arranging complicated schedules or waiting on others to show up.

JW: How long did the video documentary take to complete?

CPC: The whole project took 5½ years—from 1993 to 1998. Four of those years were spent shooting interviews and the remainder was spent in post-production and final negotiations. With a grant from the California Council for the Humanities, I was able to travel to meet Bop City musicians who had migrated further afield. In Portland, Oregon, I interviewed drummer Dick Berk (a.k.a. “Sputnik’) and vocalist Nancy King. In Los Angeles, I spoke with vibes master Terry Gibbs, trumpeter Clora Bryant, vocalist Ernie Andrews and drummer Roy Porter. In New York, I interviewed saxophonists Frank Foster and Dewey Redman, flutist Jerome Richardson and pianists Richard Wyands and Billy Taylor. Then I went on to Washington, D.C., to interview Patricia Willard, jazz consultant with the Library of Congress and former publicist for Duke Ellington.

JW: All before the Internet.

CPC: Tracking down musicians was a laborious word-of-mouth process then. With my professional background as a database analyst, I kept copious records and arranged the interviews into a logical storyline. At times, I worried that the project would never be completed. Jimbo was in his mid-80s by then, and I wanted him to see the final documentary. He had become like a second father to me.

JW: Jimbo’s Bop City was in a building with an interesting past regarding mobility, yes?

CPC: Yes. The club at 1690 Post Street closed in 1965, 19 years before I arrived in San Francisco. Everyone assumed that the building that housed the club had been demolished during urban renewal, along with so many other Victorian structures in the district. While researching similarly defunct Fillmore clubs, I spent hours in the basement of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, going through their archives of boring real estate photos. In the process, I found a shot of the empty Bop City building dated after the mass destruction of the neighborhood. Which was bizarre. The building in which the club was housed had been left standing while many others in the area had been plowed down.

JW: Wow, that is amazing—and strange.

CPC: Following this lead, I located the actual building in San Francisco and was able to prove that it had been uprooted and transported a block down the street and around the corner. During that phase of urban renewal, it was not uncommon for a Victorian house in good condition to be jacked up, hoisted onto a giant flatbed truck and trundled slowly in the dead of night to a different location.

JW: That must have been a mind-blower.

CPC: It was. When I found the building, Marcus Books occupied the space, so I was able to enter the noble room where music history had taken place. The city eventually declared it an historic heritage site.

JW: How many interviews did you bank away?

CPC: During my years of shooting, I acquired roughly 50 hours of interviews—for what was we planned would be a one-hour documentary. Definitely overkill, but there was a reason. Pianist Stanley Willis and saxophonist Pony Poindexter were fixtures on the bandstand at Bop City. They popped up in many artist interviews, usually accompanied by a chuckle or flash of pride. Both had died before I began the project, so I never got to meet them. This lent a sense of urgency to my efforts. I wanted to record as many people as I could while they were still with us.

JW: Who were your most important gets?

CPC: Saxophonist John Handy was one of the first interviewees. We subsequently became good friends, and he served as content advisor to the project. Likewise, drummer Earl Watkins was involved from day one. He became another good friend who provided content advice and good cheer during the slow days. Both of these men also arranged introductions to important Los Angeles musicians. John Handy took me to meet fellow saxophonist Teddy Edwards, who gave me a hilarious interview. Behind the scenes, Earl Watkins urged his gruff friend and fellow drummer Roy Porter to be nice to me, which he definitely was. Earl and John opened many doors.

JW: How did all of those hours of interviews translate into tapes?

CPC: I had at least 70 videotapes that ran 60 minutes each. They included interviews, cutaway footage, voice-over narration and music clips. I built a database to log everything: who was on which tape, the date, location and so on. Nowadays, there is software to transcribe interview materials directly from video footage. But back then, I had to type out the whole interview to get a written record. I created another database to log topics and where the clips could be found on which tapes. Yet another database was created to log computer disks containing digitized photos.

JW: That was a ton of work.

CPC: Shooting interviews was the fun part, but as you can see it was way more work than that. Sometimes I would track down musicians but they refused to participate. Most people were happy to cooperate, though. They seemed pleased that someone valued their memories. [Photo above of tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves and pianist Flip Nunez at Bop City, courtesy of Carol P. Chamberland]

JW: You made the documentary before tape was digital. Was that problematic?

CPC: Yes, videotape was analog when I started the project. Midway through, video went digital, so I learned the new editing software and found an edit suite at an affordable rate. Luckily, my day gig involved writing computer software, so I had a leg up on the transition to digital.

JW: What kept the film from being released commercially?

CPC: Even though I had some grant funding, the total wasn’t enough to cover commercial music rights. Archival footage from KQED-TV was licensed to me for educational purposes at no cost. But the music companies wanted full-price rights, with a “most favored nation” clause, meaning one company couldn't cut me a deal. They all had to get the full rate. Sometimes I replaced a song because the rights battle was so ridiculous. I got around the recording rights by using locally performed pieces that I recorded myself and paid a stipend to each of the musicians on the track. Given all of these hurdles, the finished product was never commercially promoted. It has been on public television—KQED—and various film and jazz festivals over the years. Some libraries purchased copies. The music-rights issue kept me from producing any further music videos, though I have enough material in the can for a documentary on bluesmen Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

JW: How much more footage do you have of the film’s artists?

CPC: Some 50 hours of interviews. If you do the math, that leaves 49 hours of unused material. The video was released in 1998 and has developed a low-key life of its own. But those remaining tapes have nagged at me from their storage location all these many years. Much of the interview material was tangential to Bop City, or it was a different story that was already covered. For example, musicians, employees and jazz fans shared personal memories that shed light on American social conditions of the 1950s and 1960s.

JW: Such as?

CPC: Their commentary covered civil rights, the transition from big bands to rock ‘n’ roll, women’s place in society, the life of traveling musicians, and more. These tales begged to be heard, so I finally wrote a book draft, just as Jimbo had always wanted. It is a poignant view of American history through a jazz lens. Most of the interviewees are now deceased. When Jimbo suffered a fatal heart attack in 2000, he left his precious photo albums to me—so they are available to augment the book if it’s published. It turns out though, that writing the book was the easy part. After two years of trying, I have not found a publisher willing to take it on. Here we go again.

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.