Home » Jazz Musicians » Jimmy Knepper

Jimmy Knepper

Jimmy Knepper, a jazz trombonist best known for his productive but stormy association with Charles Mingus. Over the course of a career that began when he was in his teens, Mr. Knepper was a featured soloist in countless bands, big and small. But his reputation as one of the most original trombonists of his generation rests largely on the music he made with Mingus from 1957 to 1962. Mr. Knepper's distinctively gruff sound and loose-limbed phrasing were essential elements in some of the most celebrated albums by Mingus, the great bassist and composer, including ''The Clown,'' ''Tijuana Moods'' and ''Mingus Ah Um.'' The jazz critic Leonard Feather wrote that Mr. Knepper's ''solos with Mingus are intricate, beautifully structured and complete statements.'' But relations between the plain-spoken Mr. Knepper and the notoriously volatile Mingus were often tense, and they came to an abrupt and violent turning point during preparations for a New York concert in 1962. Mr. Knepper recalled in a 1981 interview with Lee Jeske of Down Beat magazine that in the course of an argument about Mr. Knepper's role as music copyist for the concert, Mingus ''just kind of slapped me in the mouth,'' and the blow ''just happened to break off my incisor.'' The injury seriously affected Mr. Knepper's embouchure; it took him several years to regain his full range on the trombone. Mingus was convicted of third-degree assault (his sentence was suspended), and a fruitful collaboration was seemingly ended forever. Surprisingly, though, Mr. Knepper worked with Mingus again in the 1970's, appearing on the album ''Let My Children Hear Music'' in 1971, at a Carnegie Hall concert in 1976 and on the last three albums Mingus recorded before his death in 1979. By January 1963 Knepper was able to play again after a fashion and was hired by Peggy Lee to back her at the Basin Street East in New York. Knepper's trombone solos and ensemble playing had been a vital part of Mingus's bands for five or six years until then. He was a vital figure in much of the composer's best work, including the albums "The Clown", "Tonight at Noon", "Mingus Oh Yeah", "Blues and Roots", "Mingus Ah Um" and the unique "Tijuana Moods" suite of 1957. During this time he had also graced bands of similar moment led by Gil Evans, with whom he recorded in 1960 his unforgettable classic feature on Where Flamingos Fly, surely one of the most beautiful and moving performances ever recorded on the instrument.

Read moreTags

Trombonist Reggie Watkins's "Avid Admirer: The Jimmy Knepper Project" Set For July 15 Release

Source:

Terri Hinte Publicity

Trombonist Reggie Watkins had the opportunity to meet trombone master Jimmy Knepper just once, shortly before Knepper’s death in June 2003. Watkins was performing in his native Wheeling, WV with Maynard Ferguson’s Big Bop Nouveau Band, and Knepper, himself a Ferguson alumnus, was in the audience. The older musician complimented Watkins after the concert and shook his hand. Little did Watkins realize that a series of remarkable circumstances ten years later would lead him to record an album of Knepper ...

read more

Bill Evans and Jimmy Knepper

Source:

JazzWax by Marc Myers

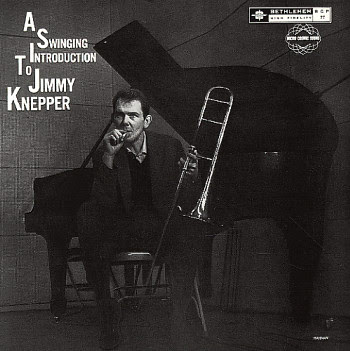

Most fans of pianist Bill Evans know him as one of jazz's great trio leaders from 1959 until his death in 1980. You also many know that in the years preceding 1959, Evans was a prolific sideman—popping up on a wide range of recordings led by superb artists such as Tony Scott, Miles Davis and Hal McKusick. One of the finest dates from his pre-Davis period was trombonist Jimmy Knepper's A Swinging Introduction from September 1957. This Bethlehem date featured ...

read more

Memorial Service For Trombonist Jimmy Knepper At St. Peter's Church On Sunday, November 9, 2003, 7:00 PM

Source:

All About Jazz

Family To Start Scholarship At New School University

This Sunday, November 9th at 7pm, a memorial service will be held for the late trombonist Jimmy Knepper at Saint Peter's Church on West 53rd Street. Knepper passed away on June 14, 2003, at the age of 76. His wife, Maxine, has requested that donations be made to the New School University Jazz Program in hopes of starting a scholarship in Jimmy's memory.

A native Californian, Knepper learned to play trombone as ...

read more