Rudy Van Gelder, a New Jersey optometrist who in the late 1940s extended his passion for ocular precision to professional recording and wound up becoming one of jazz's finest and most enigmatic studio engineers, died on Aug. 25. He was 91.

When Rudy started recording at his parents Hackensack, N.J., home (above), he knew virtually nothing about jazz. And throughout his career, he never developed much of a passion for it, despite being an ear-witness to some of jazz greatest studio performances. Rudy simply didn't have the time or the wherewithal given how much he had to get right with the studio's technology. As Rudy put it, he didn't have the luxury of listening for enjoyment. Nevertheless, he had deep respect for the extraordinary talent that came to record at the Van Gelder residence and, later, his own home-studio in Englewood Cliffs.

Being immersed in the unfolding of modern jazz in the 1950s, Rudy was inspired to experiment with his equipment in the studio. His efforts were motivated by his determination to preserve the music as he heard it and provide record buyers with the same experience. In effect, Rudy invented techniques to reproduce jazz's salon intimacy on vinyl.

At a time when setting up microphones in recording studios was fairly standard and engineers were there merely to make sure everything was plugged in and that nothing went awry with equipment or recording levels, Rudy quickly became an improviser. For Rudy, microphones had distinct characteristics and properties, and when they were placed in unusual places or wrapped in strange ways, they could produce a cozier, more realistic result.

To Rudy's credit, he always remained himself—a quiet, nerdy technician fussing with dials and wires. He never became a hipster, like so many in the jazz business did, and musicians respected his eccentricity, even when Rudy chastised them for touching or adjusting his gear. Shocked at first, they could respect that, since they, too, were guarded owners of delicate instruments. In Rudy's studio, microphones could be touched only by the sounds emanating from instruments.

Relentlessly employed by major jazz labels throughout his career, Rudy became a cult figure among record buyers and musicians. An album engineered by Rudy sounded luxurious in an understated way, as if all of the musicians had recorded in a small storage closet lined with suede. No one sounded distant, while session leaders were distinct but never overwhelming. As Rudy told me during my 2012 visit to his famed Englewood Cliffs, N.J., home/studio, where he had moved with his wife in 1959, he was constantly striving for a natural sound.

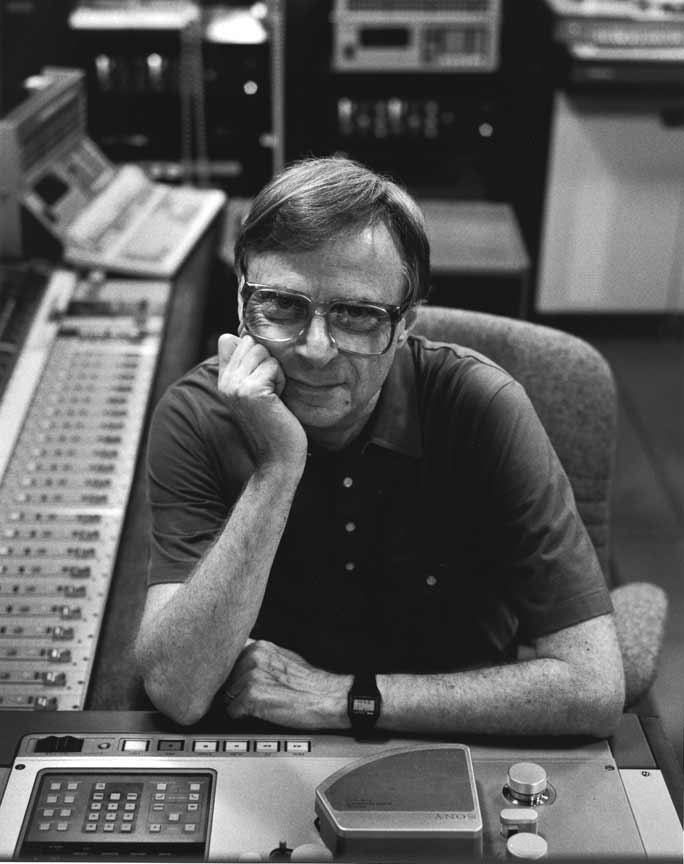

Today, I'm going to do something a little different. I know many of you cannot access WSJ.com. So below is my complete profile of Rudy for the WSJ in 2012, when I visited with him at his studio. As we ate chicken-salad sandwiches and potato chips at a tall table in the middle of his studio space, we talked for two hours about his house and all of the jazz history that was created and recorded there [photo above of Rudy Van Gelder and Marc Myers in February 2012]:

By Marc Myers

February 7, 2012

Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Rudy Van Gelder warned his guest not to trip over the thick cables snaking along the floor as we made our way through a forest of microphone stands at the far corner of his famed recording studio. “Here it is," he said, tugging a gray plastic cover off a Hammond organ. “Nearly every organist I've recorded—Jimmy Smith, Ray Charles, Jack McDuff, Charles Earland and others—used this instrument. Many people would probably be surprised to learn that it's actually a C-3 model, not a B-3."

Mr. Van Gelder is still a stickler for details. Since 1952, the 87-year-old engineer has recorded thousands of jazz albums —first at his parents' home in Hackensack, N.J., and then here. The lengthy list includes Miles Davis's “Workin'," Sonny Rollins's “Saxophone Colossus," Art Blakey's “Moanin'," John Coltrane's “A Love Supreme," Wayne Shorter's “Speak No Evil" and Freddie Hubbard's “Red Clay."

On Saturday, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences will honor Mr. Van Gelder with a Trustees Award—a Grammy that recognizes his lifelong contribution to jazz recording. As an engineer, Mr. Van Gelder is credited with revolutionizing the sound of music in the LP era—capturing the distinct textures of each instrument and giving jazz albums a warm, natural tone.

From the outside, the building that houses Mr. Van Gelder's studio looks like any chocolate-brown suburban home— except there are no windows. Inside, the butterscotch-hued, cathedral-like space features a vaulted ceiling made of laminated Douglas-fir arches and cedar planks, giving the room a Scandinavian feel. Snap your fingers or talk, and the sound appears to hang in the air momentarily, as if the rafters were evaluating the sonic quality before letting it go.

Mr. Van Gelder is notorious for stonewalling questions about his recording techniques. “But I'll tell you this," he said, seated in his studio's long control room. “I used Neumann Condenser mikes before anyone else did. I bought one of the first ones sold here. They were extremely sensitive and warm-sounding."

When asked about the creative ways he placed microphones near instruments—in one case reportedly wrapping a mike in foam and sticking it into the piano's tone hole—Mr. Van Gelder channeled his inner Sphinx. “All I'll say is nothing is simple, everything is complex."

Born in Jersey City, N.J., Mr. Van Gelder began listening to jazz on the family radio. At age 12, he ordered a home recording device that came with a turntable and blank discs. “I tried playing trumpet in my high-school marching band but I was soon demoted to ticket-taker at football games," he said. Advertisement

After high school, Mr. Van Gelder attended the Pennsylvania College of Optometry in Philadelphia. “I wanted the mental discipline and the prospect of a steady income after college." While there, he visited a network radio station. “A powerful feeling swept over me. The music, the equipment's design, the seriousness of the place—I knew I wanted to spend my career in that type of environment."

Immediately after graduating in 1943, Mr. Van Gelder opened an optometry office in Teaneck, N.J. By day he worked on eyeglasses and in the evening he recorded local artists who wanted a 78rpm record of their efforts. “I was obsessed with microphones," Mr. Van Gelder said. “When I'd see photos of jazz musicians recording or performing, I found myself looking at the mikes, not them."

In 1946, his father decided to build a house in Hackensack, N.J. Mr. Van Gelder asked for a control room with a double glass window next to the living room, which would serve as the studio. His father agreed. “The architect made the living room ceiling higher than the rest of the house, which created ideal acoustics for recording," he said.

Early clients included singer-accordionist Joe Mooney and pianist Billy Taylor. Then in 1952, Gus Statiras, a local producer, brought baritone saxophonist Gil Mellé to Mr. Van Gelder's studio to record. Mellé later played the results for Alfred Lion of Blue Note Records in New York. “Alfred wanted more tracks and went to his engineer at WOR Studios to see if he could duplicate the natural sound," Mr. Van Gelder said. “The guy told him he didn't know how, and urged Alfred to see the person who had recorded the originals. So he did."

Before long, Prestige, Savoy, Vox and other labels began booking studio time for LPs. “To accommodate everyone, I assigned different days of the week to different labels," he said. “But I continued to work as an optometrist, investing everything I made in new recording equipment."

Mr. Van Gelder learned his craft on the job. “Alfred was rigid about how he wanted Blue Note records to sound. But Bob Weinstock of Prestige was more easygoing, so I'd experiment on his dates and use what I learned on the Blue Note sessions."

As the home's driveway filled with cars, Mr. Van Gelder's parents added a separate entrance to their bedroom wing to avoid walking in on the musicians. “My parents and the neighbors never complained," he said. “Only once my mother left me a note asking me to do a better job tidying up."

In 1954, Mr. Van Gelder and his wife, Elva, moved into a nearby apartment. A museum exhibit in New York on Usonian architecture gave the couple an idea. “The image I had in mind was a small concert hall," Mr. Van Gelder said. Then came a meeting with David Henken, a Usonian architect and student of Frank Lloyd Wright. Henken designed plans for Mr. Van Gelder, and Armand Giglio, one of Henken's developers, built the studio on a wooded lot in Englewood Cliffs.

“A crane had to hoist the arches and rafters into place," Mr. Van Gelder said, pointing up at his studio's ceiling. “They were bolted together at the top and joined at the bottom with a steel cable under the floor. This design allowed for the large space to stand unencumbered by columns, which was essential for a studio."

During the 1960s and '70s, Impulse, Verve, A&M, CTI and other labels used the Van Gelder studio. “'A Love Supreme' was recorded right here," Mr. Van Gelder said. “The session was hypnotic, exciting and different. But I didn't realize that until I remastered the tapes many years later. When Coltrane was here, I was too worried about capturing the music."

Before departing, this writer tried once again to pry Mr. Van Gelder's techniques loose. “All I can tell you is that when I achieved what I thought the musicians were trying to do, the sound sort of bloomed. When it's right, everything is beautiful. I was always searching for that point."

I'm going to miss Rudy, who taught all of us that the road to success is to stick to your knitting and to make sure your knitting is better than everyone else's.

JazzWax note: For my multipart JazzWax interview with Rudy Van Gelder, start here.

JazzWax clips: Here's Rudy's first engineered jazz recording in 1949—Joe Mooney's I'll See You in My Dreams...

Here's Four Moons from Rudy's first 10-inch LP recording, Gil Melle's New Faces, New Sounds, featuring Eddie Bert (tb), Gil Melle (ts), Joe Manning (vib), George Wallington (p), Red Mitchell (b) and Max Roach (d)...

And here's Hank Mobley's This I Dig of You from Soul Station (recorded Feb. 7, 1960), with Hank Mobley (ts), Wynton Kelly (p), Paul Chambers (b) and Art Blakey (d). For some reason, this song has always reminded me of Rudy and illustrated why he was special...

When Rudy started recording at his parents Hackensack, N.J., home (above), he knew virtually nothing about jazz. And throughout his career, he never developed much of a passion for it, despite being an ear-witness to some of jazz greatest studio performances. Rudy simply didn't have the time or the wherewithal given how much he had to get right with the studio's technology. As Rudy put it, he didn't have the luxury of listening for enjoyment. Nevertheless, he had deep respect for the extraordinary talent that came to record at the Van Gelder residence and, later, his own home-studio in Englewood Cliffs.

Being immersed in the unfolding of modern jazz in the 1950s, Rudy was inspired to experiment with his equipment in the studio. His efforts were motivated by his determination to preserve the music as he heard it and provide record buyers with the same experience. In effect, Rudy invented techniques to reproduce jazz's salon intimacy on vinyl.

At a time when setting up microphones in recording studios was fairly standard and engineers were there merely to make sure everything was plugged in and that nothing went awry with equipment or recording levels, Rudy quickly became an improviser. For Rudy, microphones had distinct characteristics and properties, and when they were placed in unusual places or wrapped in strange ways, they could produce a cozier, more realistic result.

To Rudy's credit, he always remained himself—a quiet, nerdy technician fussing with dials and wires. He never became a hipster, like so many in the jazz business did, and musicians respected his eccentricity, even when Rudy chastised them for touching or adjusting his gear. Shocked at first, they could respect that, since they, too, were guarded owners of delicate instruments. In Rudy's studio, microphones could be touched only by the sounds emanating from instruments.

Relentlessly employed by major jazz labels throughout his career, Rudy became a cult figure among record buyers and musicians. An album engineered by Rudy sounded luxurious in an understated way, as if all of the musicians had recorded in a small storage closet lined with suede. No one sounded distant, while session leaders were distinct but never overwhelming. As Rudy told me during my 2012 visit to his famed Englewood Cliffs, N.J., home/studio, where he had moved with his wife in 1959, he was constantly striving for a natural sound.

Today, I'm going to do something a little different. I know many of you cannot access WSJ.com. So below is my complete profile of Rudy for the WSJ in 2012, when I visited with him at his studio. As we ate chicken-salad sandwiches and potato chips at a tall table in the middle of his studio space, we talked for two hours about his house and all of the jazz history that was created and recorded there [photo above of Rudy Van Gelder and Marc Myers in February 2012]:

By Marc Myers

February 7, 2012

Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Rudy Van Gelder warned his guest not to trip over the thick cables snaking along the floor as we made our way through a forest of microphone stands at the far corner of his famed recording studio. “Here it is," he said, tugging a gray plastic cover off a Hammond organ. “Nearly every organist I've recorded—Jimmy Smith, Ray Charles, Jack McDuff, Charles Earland and others—used this instrument. Many people would probably be surprised to learn that it's actually a C-3 model, not a B-3."

Mr. Van Gelder is still a stickler for details. Since 1952, the 87-year-old engineer has recorded thousands of jazz albums —first at his parents' home in Hackensack, N.J., and then here. The lengthy list includes Miles Davis's “Workin'," Sonny Rollins's “Saxophone Colossus," Art Blakey's “Moanin'," John Coltrane's “A Love Supreme," Wayne Shorter's “Speak No Evil" and Freddie Hubbard's “Red Clay."

On Saturday, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences will honor Mr. Van Gelder with a Trustees Award—a Grammy that recognizes his lifelong contribution to jazz recording. As an engineer, Mr. Van Gelder is credited with revolutionizing the sound of music in the LP era—capturing the distinct textures of each instrument and giving jazz albums a warm, natural tone.

From the outside, the building that houses Mr. Van Gelder's studio looks like any chocolate-brown suburban home— except there are no windows. Inside, the butterscotch-hued, cathedral-like space features a vaulted ceiling made of laminated Douglas-fir arches and cedar planks, giving the room a Scandinavian feel. Snap your fingers or talk, and the sound appears to hang in the air momentarily, as if the rafters were evaluating the sonic quality before letting it go.

Mr. Van Gelder is notorious for stonewalling questions about his recording techniques. “But I'll tell you this," he said, seated in his studio's long control room. “I used Neumann Condenser mikes before anyone else did. I bought one of the first ones sold here. They were extremely sensitive and warm-sounding."

When asked about the creative ways he placed microphones near instruments—in one case reportedly wrapping a mike in foam and sticking it into the piano's tone hole—Mr. Van Gelder channeled his inner Sphinx. “All I'll say is nothing is simple, everything is complex."

Born in Jersey City, N.J., Mr. Van Gelder began listening to jazz on the family radio. At age 12, he ordered a home recording device that came with a turntable and blank discs. “I tried playing trumpet in my high-school marching band but I was soon demoted to ticket-taker at football games," he said. Advertisement

After high school, Mr. Van Gelder attended the Pennsylvania College of Optometry in Philadelphia. “I wanted the mental discipline and the prospect of a steady income after college." While there, he visited a network radio station. “A powerful feeling swept over me. The music, the equipment's design, the seriousness of the place—I knew I wanted to spend my career in that type of environment."

Immediately after graduating in 1943, Mr. Van Gelder opened an optometry office in Teaneck, N.J. By day he worked on eyeglasses and in the evening he recorded local artists who wanted a 78rpm record of their efforts. “I was obsessed with microphones," Mr. Van Gelder said. “When I'd see photos of jazz musicians recording or performing, I found myself looking at the mikes, not them."

In 1946, his father decided to build a house in Hackensack, N.J. Mr. Van Gelder asked for a control room with a double glass window next to the living room, which would serve as the studio. His father agreed. “The architect made the living room ceiling higher than the rest of the house, which created ideal acoustics for recording," he said.

Early clients included singer-accordionist Joe Mooney and pianist Billy Taylor. Then in 1952, Gus Statiras, a local producer, brought baritone saxophonist Gil Mellé to Mr. Van Gelder's studio to record. Mellé later played the results for Alfred Lion of Blue Note Records in New York. “Alfred wanted more tracks and went to his engineer at WOR Studios to see if he could duplicate the natural sound," Mr. Van Gelder said. “The guy told him he didn't know how, and urged Alfred to see the person who had recorded the originals. So he did."

Before long, Prestige, Savoy, Vox and other labels began booking studio time for LPs. “To accommodate everyone, I assigned different days of the week to different labels," he said. “But I continued to work as an optometrist, investing everything I made in new recording equipment."

Mr. Van Gelder learned his craft on the job. “Alfred was rigid about how he wanted Blue Note records to sound. But Bob Weinstock of Prestige was more easygoing, so I'd experiment on his dates and use what I learned on the Blue Note sessions."

As the home's driveway filled with cars, Mr. Van Gelder's parents added a separate entrance to their bedroom wing to avoid walking in on the musicians. “My parents and the neighbors never complained," he said. “Only once my mother left me a note asking me to do a better job tidying up."

In 1954, Mr. Van Gelder and his wife, Elva, moved into a nearby apartment. A museum exhibit in New York on Usonian architecture gave the couple an idea. “The image I had in mind was a small concert hall," Mr. Van Gelder said. Then came a meeting with David Henken, a Usonian architect and student of Frank Lloyd Wright. Henken designed plans for Mr. Van Gelder, and Armand Giglio, one of Henken's developers, built the studio on a wooded lot in Englewood Cliffs.

“A crane had to hoist the arches and rafters into place," Mr. Van Gelder said, pointing up at his studio's ceiling. “They were bolted together at the top and joined at the bottom with a steel cable under the floor. This design allowed for the large space to stand unencumbered by columns, which was essential for a studio."

During the 1960s and '70s, Impulse, Verve, A&M, CTI and other labels used the Van Gelder studio. “'A Love Supreme' was recorded right here," Mr. Van Gelder said. “The session was hypnotic, exciting and different. But I didn't realize that until I remastered the tapes many years later. When Coltrane was here, I was too worried about capturing the music."

Before departing, this writer tried once again to pry Mr. Van Gelder's techniques loose. “All I can tell you is that when I achieved what I thought the musicians were trying to do, the sound sort of bloomed. When it's right, everything is beautiful. I was always searching for that point."

I'm going to miss Rudy, who taught all of us that the road to success is to stick to your knitting and to make sure your knitting is better than everyone else's.

JazzWax note: For my multipart JazzWax interview with Rudy Van Gelder, start here.

JazzWax clips: Here's Rudy's first engineered jazz recording in 1949—Joe Mooney's I'll See You in My Dreams...

Here's Four Moons from Rudy's first 10-inch LP recording, Gil Melle's New Faces, New Sounds, featuring Eddie Bert (tb), Gil Melle (ts), Joe Manning (vib), George Wallington (p), Red Mitchell (b) and Max Roach (d)...

And here's Hank Mobley's This I Dig of You from Soul Station (recorded Feb. 7, 1960), with Hank Mobley (ts), Wynton Kelly (p), Paul Chambers (b) and Art Blakey (d). For some reason, this song has always reminded me of Rudy and illustrated why he was special...

This story appears courtesy of JazzWax by Marc Myers.

Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.