Home » Jazz Articles » Multiple Reviews » Celebrating Blue Note Records 75th With Delicious Vinyl

Celebrating Blue Note Records 75th With Delicious Vinyl

Meade "Lux" Lewis

Meade "Lux" Lewis Melancholy / Solitude

1939

Might as well start at the inception of Blue Note Records with Alfred Lion's first release, BN 1. A record collector himself, he persuaded two pianists, Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis to record a couple of duets and series of solo sides in January 1939. Lewis had made his name in Chicago playing boogie-woogie, but Lion convinced him to focus on the blues. The two sides that were Lion's inaugural pressing of just 50 records were at 78 RPM, the custom of the day, but pressed onto 12 inch discs to allow "Melancholy" to clock in at 4:02 and "Solitude" at 4:08. The re-release is available as a limited edition Record Store Day edition 12" vinyl.

"Melancholy" lopes along via Lewis' blues locomotive rhythm. This piece of improvised music displays the emergence of what would later be the Blue Note sound. Where an artist like Fats Waller was encouraged to record silly and gimmicky songs with a ta-da component, Lion delves deeper into the heart of the music, and therefore the soul of the musician. Lewis amplifies his blues with piano flourishes, but nothing ostentatious or flamboyant. Same for "Solitude," a bar-closing blues replete with smokey notes and spiller gin. The first consumers of Lion's discs must have thought they found an entrance into another world.

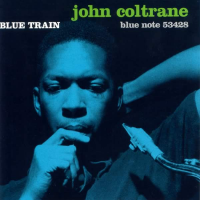

John Coltrane

John Coltrane Blue Train

1957

Except for the posthumously issued recordings with Thelonious Monk, Live At The Five Spot Discovery! (Blue Note, 1993) and At Carnegie Hall (Blue Note, 2005), Blue Train is the only recording John Coltrane made for Blue Note as a leader, and reportedly it was his favorite record.

Coltrane, in 1957 was already a star on the rise. He had gained attention with Miles Davis' 1955 Quintet, begun a lengthy association with the Prestige label, and would sign on for a lengthy gig at New York's Five Spot as Monk's apprentice. Although he would work as a Blue Note sideman on recording dates by Paul Chambers, Johnny Griffin, and Sonny Clark, this session from September was a true hard bop gem. The sound, recorded by Rudy Van Gelder, is excellent and the band (unlike sessions for Prestige) had a couple days practice to prepare.

By 1957, Lion and Alfred Wolff had establish the sound of Blue Note. That year they recorded 47 sessions. Coltrane chose a fine cast from Blue Note's stable of sidemen. Both bassist Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones were members of Miles Davis' Quintet and pianist Kenny Drew, trumpeter Lee Morgan and trombonist Curtis Fuller were steeped in the hard bop genre. Of the five compositions, Coltrane wrote four, plus the Mercer/Kern "I'm old Fashioned." Listening to "Moments Notice," and "Lazy Bird" you can discern the genesis of Trane's revolutionary chord changes that are fully realized in 1959 with the piece "Giant Steps." Professionals as they were, this was no blowing session, the music is sprite and concise.

Eric Dolphy

Eric Dolphy Out To Lunch

1964

Fifty years after the release of Out To Lunch and the question remains; where would Eric Dolphy have taken jazz if he had not died from the complications of diabetes four months after making this masterpiece? 1964 was a turning point for creative music with John Coltrane's Love Supreme (Impulse!), Albert Ayler's Spiritual Unity (ESP), and Andrew Hill's Point of Departure (Blue Note) which Dolphy was a contributor along with bassist Richard Davis and drummer Anthony Williams, who later preferred Tony Williams.

Dolphy was admired by his outward peers, playing and recording with Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and he was also a featured soloist with Charles Mingus' bands. His introduction of the bass clarinet to jazz and the flute to the New Thing created multiple possibilities for creative music.

Besides Davis and Williams, Dolphy recruited trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson to round out his quintet. Hubbard, whose hard bop horn could be heard with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers was also a a contributor to Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz (Atlantic, 1961). Davis and Williams would go on to contribute to Miles Davis' bands and Hutcherson became a fixture at Blue Note.

Out To Lunch contained five original compositions that come across as fresh today as they did in 1964. Except back then, it felt as if musicians required a license to play out. Dolphy's music is explorative, yet it maintains a harmonic center. His tribute to Thelonious Monk "Hat And Beard" marches in a rhythmic stutter-step with his bass clarinet yowling not with distress, but joy. His flute marks "Gazzelloni," a non-cliche bop piece, with butterfly flutterings that became his trademark. Dolphy's music makes a strong statement, but the interesting components here are his sideman. You can hear the foundations of Miles Davis' electric period on William's drumming, the rebirth of Hutcherson's vibraphone today in Jason Adasiewicz, and Davis' bass signaled the expressive peers that followed. Oh the places we've traveled since.

Wayne Shorter

Wayne Shorter Speak No Evil

1964

In between saxophonist Wayne Shorter's tour of duties with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers (1959-1963) and Miles Davis (1964-1970), he recorded a string of sessions for Blue Note including Night Dreamer (1964), and Juju (1964), but Speak No Evil is perhaps the best example of a hard bop saxophonist shedding one shell and taking on another persona as vibrant composer. He would later contribute pieces like "Footprints," "E.S.P.," "Pinocchio," "Nefertiti," and "Sanctuary" to the Miles Davis canon.

This session found him with former Jazz Messenger Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), John Coltrane's drummer Elvin Jones, and future Miles Davis Quintet mates Herbie Hancock (piano) and Ron Carter (bass). The seven original compositions exemplified Shorter's writing or maybe more importantly his arrangements. The (now classic) title track soars with the propulsion of a Blakey piece, but melds the fine weave of horns and piano into a more open structure for music making. Shorter had come into his own both as a composer, but also a player. He had shed the comparisons to John Coltrane, but with a piece such as "Infant Eyes" the comparisons are a must. His delivery on tenor is similar, but this ballad shows a much more delicate player and the sound more fragile.

Like all great leaders, he allows his bandmates to shine. "Witch Hunt" and "Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum" mix the rollicking tom-toms of Jones with the rhythmic percussive attack of Hancock, and Hubbard's sparkling trumpet.

Shorter's story beyond Miles includes the seminal fusion band Weather Report, and of course his acclaimed work in this new century.

Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers

Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers Free For All

1964

You can play a game, sort of like fantasy baseball, with the various musicians that have been alumni of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. Which pianist do you prefer Wynton Kelly, Benny Green, Bobby Timmons, Keith Jarrett, or Mulgrew Miller? And which trumpeter? There are so many to pick from, like Lee Morgan, Wynton Marsalis, Woody Shaw, or Kenny Dorham. Then there are the saxophonists, Benny Golson, Billy Harper, Johnny Griffin, and Jackie McLean}}, to name just a few. And we haven't got to the trombone and bass parts. The combinations and permutations are endless.

An informal poll of critics finds The Messengers' sextet (1961-64) of saxophonist Wayne Shorter, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, trombonist Curtis Fuller, pianist Cedar Walton, and bassist Reggie Workman to be the favorite all-star lineup. And Free For All, although not his finest recording, is perhaps the studio recording that most sounds like a live date. Engineer Rudy Van Gelder is barely able to contain the energy of this band in studio.

Just four tracks, the music is fierce and fiery. Opening with the title track, penned by Shorter, the energy never relents, neither does the saxophonist who blisters a solo not unlike that of his contemporary at the time, John Coltrane. Blakey can be heard shouting encouragement behind Shorter, then Fuller's solo. Next up, Hubbard dices his solo at a breakneck speed before Blakey takes a polyrhythmic solo. "Hammerhead" by Shorter is an updated version of "The Blues March" thick with that soul-groove. The band covers Hubbard's "The Core" written for CORE (Congress of Racial Equality. Then there is the samba turned Latin groove "Pensativa." Blakey has the ability to swing just as hard even on the slower tempo tunes.

Larry Young

Larry Young Unity

1965

Hammond B-3 Artist Larry Young was yang to the ying of fellow organist Jimmy Smith. Where Smith was a bluesy soul-jazz player, Young choose a John Coltrane-like sheets-of-sound approach. Eventually, he would adopt jazz-fusion, playing on Miles Davis' Bitches Brew (Columbia, 197X) and in Tony Williams Lifetime.

The high-water mark of his recording career was the 1965 session Unity one of three Blue Note discs released during his lifetime. Young died at the tender age of 38. Recorded one year after Into Somethin' (1964), the music is a showcase of the organist's discerning, dexterous approach and the advent of Woody Shaw. The 20 year old trumpeter contributes three compositions to this session, including "The Moontrane," now considered a jazz standard.

Shaw who would soon be employed by jazz legends Horace Silver, Jackie McLean, Andrew Hill, and McCoy Tyner.

Shaw's brilliance does not though, upstage the music of Young. Here he manages the cumbersome organ as if it were a harpsichord, even covering the tricky Thelonious Monk tune "Monk's Dream." The lineup here proves the merits of the sound. John Coltrane's favorite drummer Elvin Jones is accommodating to Shaw's compositions and Young's approach. Saxophonist Joe Henderson was/is regarded as the embodiment of the classic tenor. He ingested the innovations of Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, and Dexter Gordon, delivering seemingly always the perfect solo. "The Moontrane," dedicated to Coltrane, exemplifies Young's approach. The music builds upon the lyrical structure of the song, an ever spiraling sense of harmony and complexity. This band manages its development with head-scratching ease.

Tracks and Personnel

Melancholy / SolitudeTracks: Melancholy; Solitude.

Personnel: Meade "Lux" Lewis: piano

Blue Train

Tracks: Blue Train; Moment's Notice; Locomotion; I'm Old Fashioned; Lazy Bird.

Personnel: John Coltrane: tenor saxophone; Lee Morgan: trumpet; Curtis Fuller: trombone; Kenny Drew: piano; Paul Chambers: bass; Philly Joe Jones: drums.

Out To Lunch

Tracks: Hat And Beard; Something Sweet, Something Tender; Gazzelloni; Out To Lunch; Straight Up And Down.

Personnel: Eric Dolphy: alto saxophone, flute, bass clarinet; Freddie Hubbard: trumpet; Bobby Hutcherson: vibes; Richard Davis: bass; Tony Williams: drums.

Speak No Evil

Tracks: Witch Hunt; Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum; Dance Cadaverous; Speak No Evil; Infant Eyes; Wild Flower.

Personnel: Wayne Shorter: tenor saxophone; Freddie Hubbard: trumpet; Herbie Hancock: piano; Ron Carter: bass; Elvin Jones: drums.

Free For All

Tracks: Free For All; Hammer Head; The Core; Pensativa.

Personnel: Wayne Shorter: tenor saxophone; Freddie Hubbard: trumpet; Curtis Fuller: trombone; Cedar Walton: piano; Reginal Workman: bass; Art Blakey: drums.

Unity

Tracks: Zoltan; Monk's Dream; If; The Moontrane; Softly As A Morning Sunrise; Beyond All Limits.

Personnel: Larry Young; organ; Woody Shaw: trumpet; Joe Henderson: tenor saxophone; Elvin Jones: drums.

Tags

Eric Dolphy

Multiple Reviews

Mark Corroto

United States

Blue Note Records

Johnny Coles

Albert Ammons

Meade "Lux" Lewis

Fats Waller

Thelonious Monk

John Coltrane

Miles Davis

Paul Chambers

Johnny Griffin

Sonny Clark

"Philly" Joe Jones

Kenny Drew

Lee Morgan

Curtis Fuller

Albert Ayler

Andrew Hill

Richard Davis

Tony Williams

Ornette Coleman

Charles Mingus

Freddie Hubbard

Bobby Hutcherson

Art Blakey

Jason Adasiewicz

Wayne Shorter

Elvin Jones

Herbie Hancock

Ron Carter

Wynton Kelly

Benny Green

Bobby Timmons

Keith Jarrett

Mulgrew Miller

lee morgan

wynton marsalis

Woody Shaw

Kenny Dorham

benny golson

billy harper

Cedar Walton

Reggie Workman

Larry Young

Jimmy Smith

Horace Silver

Jackie McLean

McCoy Tyner

Joe Henderson

Sonny Rollins

Dexter Gordon

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.