Home » Jazz Articles » What is Jazz? » Why Hard Bop?

Why Hard Bop?

The term hard bop, like many classifications in the arts, was created by the critics. It describes the new stylistic development evolving from bebop by urban black jazz musicians who were coming into prominence in the mid-fifties. The music also incorporated the roots of jazz and African-American music, especially the blues and the music of the church. The major proponents of hard bop were Art Blakey, Clifford Brown, Horace Silver, Max Roach, Cannonball Adderley, Lee Morgan and Hank Mobley although there were numerous adherents to the style. The most popular style for black artists in a time when jazz reached it's height of popularity, it became an identification with the African-American elements of jazz for young black musicians in reaction to the west coast cool movement propagated mostly my white musicians.

The instrumentation of hard bop became very standardized taking the form of Charlie Parker's quintet of trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass and drums. Trombone can also be found in hard bop recordings but softer sounding instruments such as the clarinet or vibraphone are pretty much non-existent. Like bebop, the music is very quick moving and lively, but the hard bop sound favored a much more earthy and hard timbre in the horns and bass with a greater amount of altered pitches and bends. Solos often incorporated crescendos of hard blowing and repeated motifs. Good examples are the playing of trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and altoist Jackie McLean. The piano and bass became more facile and intricate as can be heard in the work of Horace Silver and Paul Chambers. And there was a greater interaction between the drums and the rest of the band as in Max Roach's and Art Blakey's work.

The instrumentation of hard bop became very standardized taking the form of Charlie Parker's quintet of trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass and drums. Trombone can also be found in hard bop recordings but softer sounding instruments such as the clarinet or vibraphone are pretty much non-existent. Like bebop, the music is very quick moving and lively, but the hard bop sound favored a much more earthy and hard timbre in the horns and bass with a greater amount of altered pitches and bends. Solos often incorporated crescendos of hard blowing and repeated motifs. Good examples are the playing of trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and altoist Jackie McLean. The piano and bass became more facile and intricate as can be heard in the work of Horace Silver and Paul Chambers. And there was a greater interaction between the drums and the rest of the band as in Max Roach's and Art Blakey's work.  Also like bebop there is a great emphasis placed on composition. However the hard bop musicians brought the compositional complexity to a new level. As the bebop musicians were known for harmonic substitution and alteration of standard chordal structures and popular song the hard bop musicians were more fond of creating new and challanging chord structures often with quick key changes upon which the soloist could show their prowess. A good example of this is John Coltrane's "Moments Notice." The rhythmic underpinnings of the composition were also given greater attention. Time signatures and drum patterns would change for the enhancement of the melody and would often be retained for the solo statements. Use would be made of inventive drum styles and dynamic breaks. Examples of this is are in Art Blakey's recordings of "Blues March" and "Mosaic" and in The Brown-Roach Quintet's recording of "Parisian Thoroughfare."

Also like bebop there is a great emphasis placed on composition. However the hard bop musicians brought the compositional complexity to a new level. As the bebop musicians were known for harmonic substitution and alteration of standard chordal structures and popular song the hard bop musicians were more fond of creating new and challanging chord structures often with quick key changes upon which the soloist could show their prowess. A good example of this is John Coltrane's "Moments Notice." The rhythmic underpinnings of the composition were also given greater attention. Time signatures and drum patterns would change for the enhancement of the melody and would often be retained for the solo statements. Use would be made of inventive drum styles and dynamic breaks. Examples of this is are in Art Blakey's recordings of "Blues March" and "Mosaic" and in The Brown-Roach Quintet's recording of "Parisian Thoroughfare."  The hard bop musician wanted to bring back some of the roots of the music to their playing. This was done by using earthy and gritty timbre and pitch bends as mentioned before but in also in the use of compositional structures and motifs common in the music of the church and in blues. The blues, never a stranger to jazz, was given back more of its soul and cry by the hard bop musician. There was also often a more authentic use of the chordal structure of the blues form using just the straight seventh chords without the enhancement of passing chords and alterations common to earlier forms of jazz. Examples of the blues are vastly numerous throughout hard bop. A good one though is Horace Silver's "Doodlin.'"

The hard bop musician wanted to bring back some of the roots of the music to their playing. This was done by using earthy and gritty timbre and pitch bends as mentioned before but in also in the use of compositional structures and motifs common in the music of the church and in blues. The blues, never a stranger to jazz, was given back more of its soul and cry by the hard bop musician. There was also often a more authentic use of the chordal structure of the blues form using just the straight seventh chords without the enhancement of passing chords and alterations common to earlier forms of jazz. Examples of the blues are vastly numerous throughout hard bop. A good one though is Horace Silver's "Doodlin.'"  Church music and gospel structures and motifs were also very common and the playing again emulated exuberance and soul reminiscent of the preacher and congregation in song. There are several songs which use a call and response structure between the soloist and the rest of the band and the use of the plagal or amen cadence. An example of this is Bobby Timmons' "Moanin'" among several other of his tunes recorded with Art Blakey. Timmons' playing style in general also had a very gospel feel. Another church inspired composition is Horace Silver's "The Preacher" as are several more of his tunes. Charles Mingus did extensive experimentation with church and blues forms and with passionate and soulful playing, though he was also fond of using bigger bands. Organist Jimmy Smith almost used exclusively blues and gospel styles in is playing. Other classic tunes include Lee Morgan's "Sidewinder" and Herbie Hancock's "Watermelon Man" for their gospel and R&B influences, and Nat Adderley's "Work Song" which attempts to emulate the slave songs.

Church music and gospel structures and motifs were also very common and the playing again emulated exuberance and soul reminiscent of the preacher and congregation in song. There are several songs which use a call and response structure between the soloist and the rest of the band and the use of the plagal or amen cadence. An example of this is Bobby Timmons' "Moanin'" among several other of his tunes recorded with Art Blakey. Timmons' playing style in general also had a very gospel feel. Another church inspired composition is Horace Silver's "The Preacher" as are several more of his tunes. Charles Mingus did extensive experimentation with church and blues forms and with passionate and soulful playing, though he was also fond of using bigger bands. Organist Jimmy Smith almost used exclusively blues and gospel styles in is playing. Other classic tunes include Lee Morgan's "Sidewinder" and Herbie Hancock's "Watermelon Man" for their gospel and R&B influences, and Nat Adderley's "Work Song" which attempts to emulate the slave songs.  The popularity of the hard bop style continued well into the mid sixties but was somewhat superseded by modal and free jazz in the early sixties and then completely by jazz/rock fusion in the seventies. Not all of the above mentioned aspects of hard bop are in every hard bop recording but generally you will find most artists from that period touching on much of it throughout their careers. Recording was prolific during the hard bop years and lots of great music can be found. Blue Note was the mainstay of hard bop and released many fine recordings, but there is quite a lot to be found on minor labels such as EmArcy, Riverside and Prestige. Here is a short list of the most classic recordings. If you run across a something you think is really great be sure to tell me.

The popularity of the hard bop style continued well into the mid sixties but was somewhat superseded by modal and free jazz in the early sixties and then completely by jazz/rock fusion in the seventies. Not all of the above mentioned aspects of hard bop are in every hard bop recording but generally you will find most artists from that period touching on much of it throughout their careers. Recording was prolific during the hard bop years and lots of great music can be found. Blue Note was the mainstay of hard bop and released many fine recordings, but there is quite a lot to be found on minor labels such as EmArcy, Riverside and Prestige. Here is a short list of the most classic recordings. If you run across a something you think is really great be sure to tell me. Recommended Listening

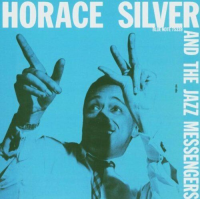

- Horace Silver, Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers (Blue Note, 1954)

- Clifford Brown/ Max Roach Quintet, Clifford Brown and Max Roach (EmArcy, 1955)

- Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, Moanin' (Blue Note, 1958)

- Cannonball Adderley Quintet, In San Francisco (Riverside, 1959)

- John Coltrane, Blue Train (Blue Note, 1957)

- Hank Mobley, Soul Station (Blue Note, 1960)

- Lee Morgan, The Sidewinder (Blue Note, 1963)

< Previous

Laila Biali is taking requests

Next >

Renderings

Comments

Tags

What is Jazz?

Art Blakey

AAJ Staff

Freddie Hubbard

lee morgan

John Coltrane

Hank Mobley

Clifford Brown and Max Roach

Horace Silver And The Jazz Messengers

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.