Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Steven Wilson: Luck's What You Make It

Steven Wilson: Luck's What You Make It

For those who liked the idea of a performance being more than just a group on a stage, playing music from an artist's recordings, Get All You Deserve reflects Wilson's multifaceted, multidisciplinary interests. With Hoile, Wilson has also developed a visual signature, one that has graced Porcupine Tree covers since In Absentia (Lava, 2002). "I've been very fortunate," says Wilson, "because, for many years, I had all these kinds of ideas in my head, but I had no personal facility to actually create them. I'm not a filmmaker, I'm not a photographer, and I struggled for most of the first 10 years of my professional career—not just with live performance but with simple things like album covers.

"Then, around 2001, along comes Lasse," Wilson continues. "Basically, he was a fan who submitted some things which totally blew me away. I looked at the pictures and thought, 'Yeah, that's exactly what I imagined. That's what I see in my head, those kinds of relationships.' I think you're lucky if it happens once to you in your career that there's that kind of symbiotic thing between you and another musician or you and another artist, or you and another discipline, in this case. And that's exactly what happened with Lasse. I know that I can just explain what the song is about, what I see in my head and perhaps some cinematic references, and he'll go away and come back with something that's exactly what I'd hoped for and imagined it would be. That is such a rare thing to find. I've never had that with a musician, ever. The closest I've had with a musician is with Mikael Akerfeldt, who is the singer with Opeth; he has similar kinds of ideas and musical tastes. But really, Lasse is the closest I've ever gotten to that kind of symbiosis, and it's fantastic because it means that we are able to collaborate on these kinds of audiovisual experiences."

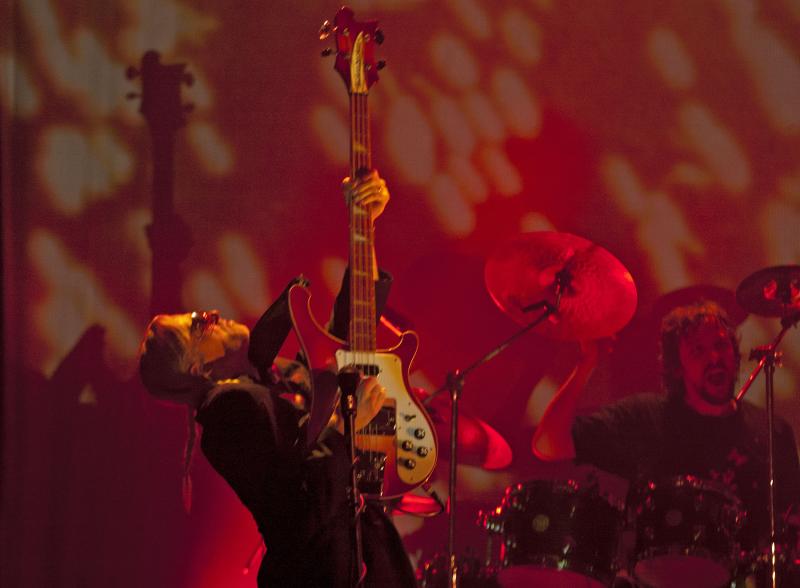

In addition to providing the onstage visuals for Get All You Deserve, Hoile also directed the concert film, and it's helped to create something identifiable not just musically but visually as well. By sequencing the music carefully, introducing evocative imagery throughout and paying attention to every minute detail, Get All You Deserve is a potent live document of Wilson and his band. "I am trying to create the sense of a journey throughout the show," Wilson explains. "What I mean by that is different things are happening all the way through the show. So there's not a sense of stasis at any moment. Just when the show seems like it might be settling, some other new kind of gag will come along, whether it's a new film, or it's me coming out with my gas mask or whatever; something else is always grabbing the audience back in. I think that's important.

It's also important, Wilson continues, "to recognize that there are more bands out there on the road now than at any time ever before in the history of rock music because, firstly, there are just more people out there making music than ever before. It's relatively easy to get yourself set up at home, making music, and the next logical thing is to go out and play live. But the other reason is, of course, that you can't make money any other way. You have to go out and play on the road if you want to be a professional musician. So there are more bands out there than ever before, and the competition for the small amount of money people have to buy concert tickets is phenomenal, so you really have to give something. You have to make something that differentiates you from everyone else.

"I think that I was aware of this right from the beginning when I wanted to go out and do my first solo tour," Wilson concludes. "I could've so easily have just gone out with a guitar and an electric piano and done this sort of Peter Hammill [of Van der Graaf Generator] thing; I could have easily done that, and I think that, for a lot of people, that's what they expected. But I said, 'No, I'm going to go out with something even bigger than I did with Porcupine Tree, and hopefully everyone that comes along will go away talking about it to their friends. I think that, with that word of mouth, it will be interesting to see if it's actually worked this time around."

Anti-synthetic, Anti-snob

Based on the crowd in Montreal, and the sold-out show at Mexico City's Teatro Metropolitan, where the Get All You Deserve was recorded, it sure seems to be working. And as modernistic as the technology driving the performance is, underneath it all is an organic sound that, curiously, comes from instruments that some people would have trouble thinking of as such. "It is bizarre. I think of the whole musical palette from that era [1970s] as very organic, and a whole load of instruments which are electric instruments that sound—and I know it sounds like an oxymoron—organic to me. The mellotron, for me, is an incredibly organic-sounding instrument—the kind of scratching sound of the tape heads going down on a piece of analog tape—these things for me, at least in my terms, are very, very organic. In a way, they're not electric even though they are. They're not synthetic; I think that's a better word. They're kind of anti-synthetic, so they really feel like flesh and blood: living, breathing instruments. And they don't date, for me. In fact, those instruments sound timeless to me. I would put Hammond organ, mellotron and Fender Rhodes alongside the grand piano as kinds of instruments of sound that don't seem to date at all; they have a certain golden quality."

If Get All You Deserve reflects a confluence of organic sounds, stunning visuals, musical unpredictability and layered writing, performed by a band that brings its own mélange of styles to the table then, among Wilson's exceptional sextet, the biggest surprise may be Nick Beggs. "Nick is someone a bit like myself," Wilson explains. "He doesn't really get the musical snobbery thing at all; for Nick, playing in Kajagoogoo or with [singer] Kim Wilde is just as much fun, just as inspiring as playing with [bassist] John Paul Jones, my band, or with Steve Hackett. And I've always felt that, too. When people talk to me and they ask me what my influences are, I mention people like Abba and The Carpenters, and the kind of reaction I get sometimes is a chuckle or a sarcastic kind of 'knowing.' And I'm not being sarcastic, I'm not trying to be postmodernist, and I'm not trying to be ironic. I think those records are extraordinary. Abba's Arrival (Polar, 1976) is just as extraordinary as any progressive rock or so-called serious record. And I think that Nick is totally like that, too; he gets just as much buzz from playing with Nik Kershaw as he does with Steve Hackett as he does with John Paul Jones as he does with Kim Wilde as he does with me, and I like that about him—this complete lack of musical snobbery."

Lizard and Remixing the King Crimson Catalog

What's been particularly noteworthy about Wilson's solo career is its synergy with his remix work on the King Crimson catalog—two seemingly different pursuits that nevertheless seem to be informing each other. His surround mixes have gone beyond simply providing a new way to hear the music, however; instead, Wilson has, in most cases, repositioned them with the kind of clarity and transparency that allows them to be better appreciated by those who might have dismissed them the first time around ... and that sometimes even includes the artists themselves.

"Lizard is incredibly congested," says Wilson. "One of things I said about Lizard that I still think is actually true is that it is an album that stereo could not contain; there is so much going on in that record that it simply was not possible to somehow capture it all within the stereo spectrum. I think I implicitly knew that from the beginning, because I remember when Declan [Colgan, head of Panegyric Records, releasing the Crimson series] said to me, 'Which album do you want to do first?' And I said I wanted to do Lizard first.

"I think I'd done Discipline (DGM Live, 1981) as a test, but when they said were going to do the whole project, I said to Robert [Fripp] and Declan, 'I want to do Lizard.' And they looked at me like I was demented," Wilson continues. 'Why do you want to do that record?' And I said, 'I'm gonna change peoples' minds about it,' and one of the things that I'm most proud of is that I think we did it. We did change peoples' minds about that record; I hear people raving about that record now. For years, people dismissed Lizard as Crimson's 'problem child.' Robert was one of the people who also dismissed it. I think one of the reasons that it never worked as well as it could have was that the original stereo mix was not great to start with, and even more so because there was so much information in the music; it was just crying out for a multichannel treatment.

"I kind of approach the 5.1 thing like an idiot savant," continues Wilson, "because I've never listened to anyone else's 5.1 mixes, and I just approach it with the point of view of what seems right. What I was really surprised to find, in retrospect, is that what I thought was right, a lot of other people listening to it thought was right as well. If you go from mono to stereo, you don't have things whizzing between the speakers just because you can; why would you do that in 5.1? I love the simple beauty of sound. Forget the musician. Just the sounds are beautiful: hearing the decay of a beautiful piano note and all the harmonics it throws off, the sound of hitting a note. It's a beautiful sound in the hands of a great musician. That's the best possible thing in the world.

"I don't understand people who make these rules for themselves," Wilson concludes. "I've had people come up to me and say, 'You shouldn't remix albums; you shouldn't tamper.' 'Uh, okay, why exactly?' The answer: 'Because that was the way they [the artists] intended it.' No, actually; if you talk to Robert, you'll see that a lot of those [Crimson] records were mixed under duress, under time constraints and under financial constraints, with all kinds of inter-band politics going on. So they were never mixed the way they wanted, and now they are. People said that about [Jethro Tull's] Aqualung (Chrysalis, 1971), and I found that what was on the tapes sounded very good. I think that one of the great things about that particular mix is that it proves that what they recorded in the studio was very good, it was just the mix that had gone wrong. And you can do a lot now; you can do so much with modern technology to make things sparkle. I'd love to do Soft Machine's Third (Columbia, 1970)."

"I don't understand people who make these rules for themselves," Wilson concludes. "I've had people come up to me and say, 'You shouldn't remix albums; you shouldn't tamper.' 'Uh, okay, why exactly?' The answer: 'Because that was the way they [the artists] intended it.' No, actually; if you talk to Robert, you'll see that a lot of those [Crimson] records were mixed under duress, under time constraints and under financial constraints, with all kinds of inter-band politics going on. So they were never mixed the way they wanted, and now they are. People said that about [Jethro Tull's] Aqualung (Chrysalis, 1971), and I found that what was on the tapes sounded very good. I think that one of the great things about that particular mix is that it proves that what they recorded in the studio was very good, it was just the mix that had gone wrong. And you can do a lot now; you can do so much with modern technology to make things sparkle. I'd love to do Soft Machine's Third (Columbia, 1970)." Lizard was a transitional album, as Fripp—the only remaining original member by this time—struggled to find a stable touring lineup. The result, with a wealth of guests including pianist Keith Tippett, cornetist Mark Charig and trombonist Nick Evans, was the closest thing to a jazz record Crimson ever made. "I think there are many things to say about Lizard," says Wilson. "It's the only album in the King Crimson catalog that's basically a Robert Fripp solo record, and I think that is one of the things that makes it so very distinctive. For years, Robert really didn't enjoy listening to it or talking about it, but I think he's since come to appreciate it. I've never been particularly interested in pure jazz; I don't dislike it, it's just not my thing. But I love jazz hybrids. I love music that has elements of jazz, whether it's the ECM catalog or progressive rock bands like Magma, Crimson, Tull and some of the Kraut rock bands. But that idea of combining music seems to be less easy to do these days. I think part of the reason—the same problem, probably, that was always there—is how do you sell music that is not generic?"

Never More Open, Never More Generic

"One of the things that's interesting about the era we live in now is, in some ways, it's never been more open, because it's liberated from the control of the record companies, and it's liberated from the control of television and commercial radio," continues Wilson. "But, at the same time, I feel music has never been more generic. And I think that's one thing that was kind of unique—I was going to say unique to the early '70s, but it's also true of the early '80s. When I go back and listen to so-called post-punk bands like Joy Division, Magazine and XTC, I feel that they have more in common with the early '70s progressive rock bands than they did, in hindsight, with The Sex Pistols and The Clash.

"If you analyze what Joy Division did, it's very weighty, lyrically," Wilson continues. "It's all about the human condition, and the songs are both portentous and pretentious. And all this stuff—it's progressive rock; it's absolutely prog rock. It may not be played with the same musical technique as a band like Pink Floyd played 10 years earlier, but it's still basically progressive rock. Or at least that's the way it seems to me. So the early '70s and early '80s, for me, are kind of parallel, in a way. But what we've lost now is that people don't necessarily work too much across genres anymore, and I think the audience is partly to blame for that because there's incredible resistance to creating music that goes across genres. Some people talk about my music being jazzy now; well, some people don't like that.

"The problem with rock music and dance music is that they are quite resistant to changing the format of a performance," Wilson concludes. "You come along, you go to the bar; you get your beer, stand and watch the support band for 30 minutes; you go to the bar again and see the show; you scream a lot for the band and they come back for an encore. It's a very traditional format. The fans are quite resistant, and I like the fact that the electronic and jazz worlds are much more open."

Still, Wilson seems to be making headway. One of the most exciting tracks on Get All You Deserve is "Luminol," a new tune that's both a sneak peak at his forthcoming studio record and the first tune he's written with his band in mind. "Yeah, that was an experiment," Wilson admits. "It's funny; I did this once with Porcupine Tree, where we went out and played a whole new record before we went into the studio. It was something that people did all the time in the '70s, and I understand why people don't do it now, because the whole download culture has unfortunately made people paranoid about performing new material. But in 2007, before we did Fear of a Blank Planet (Roadrunner, 2007), we said, 'Fuck it, let's go and play the whole record. We haven't recorded it yet, so let's road test it.' It's amazing how much more the music starts to live and breathe when you finally go into the studio to record it. You have explored all the possibilities.

"The interesting thing about that is that it's another thing that I pretty much realized from remixing these old records—the Crimson, the Tull, the ELP—all the records I've been doing the last few years," Wilson continues. "A lot of these guys were recording these albums almost on the fly. They'd be out doing shows six days a week. They'd be playing the songs, and the studio was just something they popped in on when they had a spare day. And they would cut exactly what they were playing on the road. They'd set up in the studio as a band, the engineer would get a basic sound, they'd play their set—they'd play exactly the same set that they played the night before or two days before—and the engineer would mix it, and that was it. That was an album.

"Now it's become the other way around," continues Wilson, "which is, you basically go into hibernation and write an album, you record it in a fairly clinical way, and only then do you start thinking about playing live. But, of course, only when you start to play live does it start to really live and breathe, and I've realized that hearing these guys play some of the music that I recorded on Grace for Drowning—and I thought that recording is pretty vibey—now they've gone to a whole new level. So that was part of the reason for going out and playing "Luminol" live; it's an old-school thing to do.

"I also liked the idea of documenting a band at its inception, which is not something that usually happens," Wilson concludes. "This is a band that has not even made a studio recording together, and yet we've made a live DVD. And I'm sure we'll only get better and make more and more live documents. But I think it was an interesting thing to do, to document this. You don't really know it's going to work until it's actually performed in front of an audience. My manager, Andy [Leff], was there that night, and Lasse was there that night. But to me, what was surprising was that by the end of that show, everybody felt that it was just one of those moments in life when it was pure luck, and it all worked out so well."

Wilson is currently busy working on the new album, set for release by the beginning of March 2013, when he'll hit the road for nearly a year of heavy touring. In the meantime, Get All You Deserve and video clips from the new recording dates make one thing clear: that the serendipitous confluence of Wilson, Holzman, Travis, Govan, Beggs and Minnemann, already at the top of their game, is going to make 2013 a year to remember for fans of progressive music that may not be jazz—or even jazzy—but which leans heavily on its risk-taking spirit, improvisational heart and linguistically sophisticated mindset.

Selected Discography

Steven Wilson, Get All You Deserve (Kscope, 2012)

Storm Corrosion, Storm Corrosion (Roadrunner, 2012)

Steven Wilson, Catalog | Preserve | Amass (Self-produced, 2012)

Steven Wilson, Grace for Drowning (Kscope, 2011)

Bass Communion, Cenotaph (Tonefloat, 2011)

Incredible Expanding Mindfuck, Complete I.E.M. (Tonefloat, 2010)

Steven Wilson, Insurgentes (Kscope, 2009)

No-Man, Schoolyard Ghosts (Snapper, 2009)

Bass Communion, Loss (Soleilmoon, 2006)

Blackfield, Blackfield (Snapper, 2004)

Porcupine Tree, In Absentia (Lava, 2002)

Porcupine Tree, Lightbulb Sun (Kscope/Snapper, 2000)

Porcupine Tree, Stupid Dream (Kscope/Snapper, 1999)

Bass Communion, I (3rd Stone, 1998)

Porcupine Tree, The Sky Moved Sideways (Delerium, 1995)

Porcupine Tree, On the Sunday of Life (Delerium, 1991)

Photo Credits

Page 1: Courtesy of Steven Wilson

Page 2: Mr. Sayer

Pages 3, 5: John Kelman

Pages 4, 6: Lasse Hoile, Courtesy of Steven Wilson and Kscope Music

< Previous

En Corps

Comments

About Steven Wilson

Instrument: Composer / conductor

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

steven wilson

Interview

John Kelman

United Kingdom

London

Yes

Genesis

Jethro Tull

Gentle Giant

Van der Graaf Generator

Hatfield and the North

Soft Machine Legacy

Miles Davis

Led Zeppelin

The Beatles

Theo [Travis]

Adam [Holzman]

Robert Fripp

Gong

Eddie Jobson

Mike Keneally

Alex Machacek

Trey Gunn

Adrian Belew

Steve Hackett

Jordan Rudess

Dave Liebman

Keith Tippett

Nick Evans

Kscope Music

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.