Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Power, Passion and Beauty: The Story of the Legendary Ma...

Power, Passion and Beauty: The Story of the Legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra

Walter Kolosky

Paperback; 313 pages

ISBN 0-9761016-2-9

Abstract Logix Books

2005

Anyone who's old enough to have experienced the Mahavishnu Orchestra's debut The Inner Mounting Flame (Columbia/Legacy, 1971) when it was first released knew—whether they liked it or not, whether they understood it or not—that a sudden and monumental shift in modern music had just taken place.

Sure, others had begun combining the improvisational prowess of jazz with the volume and energy of rock. Drummer Tony Williams, whose Lifetime band featured British guitarist John McLaughlin—who formed the Mahavishnu Orchestra in the first place—had released Emergency! (Polydor, 1969), a raw sonic assault on the senses that, nevertheless, retained the clear earmarks of jazz. Williams' ex-boss, trumpeter Miles Davis, had been experimenting with rock rhythms as early as Miles in the Sky (Columbia/Legacy, 1968) but once again shattered his own conventions in a much more profound way with the one-two punch of In a Silent Way (Columbia/Legacy, 1969) and Bitches Brew (Columbia/Legacy, 1969).

But The Inner Mounting Flame represented an entirely different approach. Like Lifetime, it was LOUD. But unlike both Lifetime and Davis' efforts, there was a stronger compositional focus that included irregular meters, Indian harmonies and vivid counterpoint—all played, more often than not, at mind-numbing speeds that few others could match. But despite concert volumes that were so powerful that they sent some running from the venues, the Mahavishnu Orchestra was also capable of great beauty. And whether they were playing the almost impossible-to-conceive blinding theme of Inner Mounting Flame's closer, "Awakening, or the brief acoustic respite of "A Lotus on Irish Streams, the passion of McLaughlin, keyboardist Jan Hammer, violinist Jerry Goodman, bassist Rick Laird and drummer Billy Cobham was inexorable and undeniable.

Considering its significance, what's surprising is that it's taken so long for someone to write the story of the Mahavishnu Orchestra, a group that may not have been the first jazz/rock outfit, but was undoubtedly the most influential and successful—despite the brief existence of its first and most important incarnation. The good news is that Walter Kolosky's Power, Passion and Beauty: The Story of the Legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra has finally arrived after years of research and interviews, and it delivers on the expectation of anyone whose life has been inextricably changed by the initial incarnation of the group.

Subtitling the book The greatest band that ever was, Kolosky makes no bones about the fact that, for him, the Mahavishnu Orchestra represented a clear musical pinnacle—the musical pinnacle, in fact. But he's not alone. Intrepid drummer/percussionist Gregg Bendian's Mahavishnu Project, a tribute band that does more than simply recreate the music of the Mahavishnu Orchestra, but treats it as repertory classical music to be explored, torn apart and reinterpreted, has been met with open arms—and not just by Mahavishnu fans eager to hear the music in live performance (many of them too young to have experienced the real thing). At the Bendian-organized three-day Vishnu Fest that took place last year in New York City, McLaughlin attended the first night, while Laird and Hammer were on hand for the final evening, which paid tribute to The Inner Mounting Flame. By every account a grand time was had by all.

While Kolosky's passion for the group is evident from the first page to the last, he rarely imposes himself on the reader. Instead, a relatively chronological history of the band is presented through the words of those who lived it: the members of the group, the roadies, the managers and agents, and the almost countless musicians—many of whom, like guitarists Pat Metheny, John Scofield and John Abercrombie, have gone on to greater fame themselves.

What becomes clear, when reading of the first Mahavishnu Orchestra, is how its coming together was one of those rare confluences where everything lined up perfectly. In the same way that Miles Davis' Kind of Blue (Columbia/Legacy, 1959) would likely not have come about the way it did had it taken place a year earlier or later, the first Mahavishnu Orchestra would not have been the same group had it not been there at just the right place, exactly the right time. Every member's contribution was of equal importance—McLaughlin's voracious interest in music and Indian culture/spirituality, Goodman's classical and rock background, Cobham's muscular approach to groove, Hammer's distinctive guitar-like voice on Minimoog and Rick Laird's unmovable anchor, consistently creating a fixed frame of reference regardless of the maelstrom that was going on around him.

Laird was, in fact, the most consistently-overlooked member of the band and Kolosky goes to significant length to explain just how critical his role was. Surrounded by virtuosos who were often soloing at the speed of light, Laird seemed an odd choice. Rarely soloing himself, Laird's sometimes hypnotically-repetitive lines seemed at odds with the rest of the group. But another bassist—perhaps one like Stanley Clarke who was more extroverted and excessive—would have completely altered and likely destroyed the delicate balance of the group's diverse musical personalities. What also becomes clear is that while Laird's playing may have appeared simple, his harmonic knowledge had to be as strong as those around him; in order to find the unifying thread to tie everyone else's more outer-reaching explorations together he had to make the right decisions, which he did every time.

Kolosky doesn't sugar-coat the group's conflicts. This was, after all, a band that essentially imploded after only two studio albums—ignoring the more recently-discovered third album The Lost Trident Sessions (Columbia/Legacy, 1999), recorded in 1973—and one live record. But he doesn't exploit them either. While there are clearly some unresolved issues between various members of the group, there has also been a certain degree of forgiveness as well, and to some extent Kolosky can take responsibility for that by encouraging each member of the band to open up and talk about the events surrounding the group's beginning, rise to success and ultimate dissolution.

Kolosky also tackles the delicate subject of spirituality with an approach that makes it clear that McLaughlin's personal search was unquestionably responsible for his extreme dedication and the musical directions he chose. But thankfully Kolosky avoids making any value judgements. The biggest strength of Power, Passion and Beauty is how Kolosky, despite being a huge fan, lets the story tell itself rather than injecting too much of his own viewpoint, in direct contrast to Paul Stump's more easily contestable Go Ahead John: The Music of John McLaughlin (SAF Publishing, 1999).

If there's a weak point in the book it's in Kolosky's attempts to provide blow-by-blow descriptions of individual compositions. While any music critic's greatest challenge is to articulate in words the indescribable entity that is music, it's perhaps best to describe it in more general terms rather than becoming too specific.

But it's a small quibble as Kolosky doesn't focus the emphasis of the book on the Mahavishnu Orchestra's admittedly groundbreaking repertoire—again, in contrast with The Last Miles: The Music of Miles Davis 1980-1991 (University of Michigan Press, 2005) where author George Cole, despite having interview footage every bit as good and revealing as Kolosky's, spends far too much time dissecting each and every song Davis recorded in his last decade of life. How many ways can you say funky?

While the original Mahavishnu Orchestra dissolved at the end of 1973 and, being the most significant incarnation of the group gets the majority of Kolosky's attention, he does detail the second version that included, amongst others, violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, drummer Narada Michael Walden and bassist Ralphe Armstrong. Kolosky also gives relatively short shrift to the 1980s incarnation, simply called Mahavishnu (despite McLaughlin having long abandoned the teachings of his 1970s guru, Sri Chinmoy). But there's no doubt which version of the band Kolosky is referring to when he describes The greatest band that ever was.

It's been over 30 years since McLaughlin, Hammer, Goodman, Laird and Cobham have played together. Every one of them has gone on with their lives, some to greater success than others and one—Laird—giving up performing entirely and finding another artistic outlet in photography. Kolosky rightfully focuses on just how vital each of them was in the day and, despite the passage of time and considerable diversification, continues to be.

There are those who still look back fondly on other fusion groups of the time—keyboardist Chick Corea's Return to Forever, keyboardist Joe Zawinul and saxophonist Wayne Shorter's Weather Report and keyboardist Herbie Hancock's Headhunters. But while they weren't the first jazz/rock group by a long shot, the Mahavishnu Orchestra effectively fired the first major salvo that made the early to mid-1970s a heyday of artistic creativity—a time when anything and everything was possible. A time when major labels would put serious money behind groups that, were they to emerge today, would be relegated to smaller independent labels or be forced—as is the case with Bendian's Mahavishnu Project—to self-publish.

The three albums released during the Mahavishnu Orchestra's brief existence—The Inner Mounting Flame, Birds of Fire (Columbia/Legacy, 1972) and Between Nothingness and Eternity (Columbia/Legacy, 1973)—continue to sell today, building a following of new fans, many who weren't even born when the group was active. With Power, Passion and Beauty, Kolosky has finally righted a wrong, delivering a book that is as factual an account of the group's rise and fall as will likely ever be published.

The subtitle, The greatest band that ever was may prove hyperbolic for some, but clearly not for Kolosky. Absolutes aside, the Mahavishnu Orchestra's importance in the history of not only jazz, but music in general, cannot be underestimated or overlooked. Power, Passion and Beauty: The Story of the Legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra will ensure that those unfortunates who missed the emergence of the Mahavishnu Orchestra can live vicariously through the clearly articulated experiences of the many people who contribute to what is, ultimately, a terrific story beautifully told.

Visit the Interactive Mahavishnu Book website for more information.

Tags

Comments

About Mahavishnu Orchestra

Instrument: Band / ensemble / orchestra

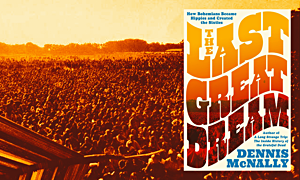

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.