Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Becoming Ella Fitzgerald

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald

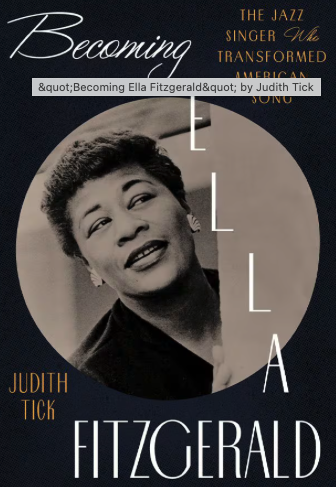

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald Judith Tick

560 Pages

ISBN: 978-0-393-24105-1

W.W. Norton & Company

2024

In his 859-page monograph The Swing Era (1989), composer and historian Gunther Schuller skipped past Ella Fitzgerald. In 2011, when Judith Tick asked him about the omission, he responded that "there wasn't room to cover two singers, and he had chosen Billie Holiday" (Becoming Ella Fitzgerald, p. 429). Tick's meticulously researched and insightful Becoming Ella Fitzgerald fills that hole and others like it. As she put it, "This void demanded my attention. As a music scholar and a feminist, I felt personally challenged to fill it, to look at the ways patterns of gender bias in earlier American music were echoed in post-1950s jazz. This has enabled me to question the reductive oppositions between popular singing and jazz singing, between Billie Holiday and Ella, and between art and entertainment" (p. XXI).

Tick modestly describes herself as a "second wave feminist historian who contributed to the development of women's history in Western classical music and in American musical life," which qualifies her extraordinarily well for the project. There are other biographies of Fitzgerald—Stuart Nicholson's Ella Fitzgerald (1993) and Rainer Nolden's Ella Fitzgerald: Ihre Leben, Ihre Musik, Ihre Schallplatten (1986) among them—but Becoming Ella Fitzgerald is the first to profit from digital access to a huge variety and number of resources heretofore hidden in special collections and archives scattered across the US and elsewhere. A distinguished professor emerita of music history at Northeastern University and award-winning author, Tick took full advantage of these materials in two decades of research and writing, focusing primarily on "three neglected aspects of her life and work": the early part of Fitzgerald's career, her private life and ways in which her improvisations "link musical practice with lived experience."

Newly available articles in African American and European presses provided insights into Fitzgerald's early career through candid interviews and coverage of tours abroad and in "colored show business" within the US. She sought eyewitnesses as well; friends, neighbors and fans such as Norma Miller, a swing dancer and contemporary of Fitzgerald's, who watched Fitzgerald rise to prominence in Harlem. Pursuing Holiday-versus-Fitzgerald as a historical thread, Tick notes that, according to Miller, by 1938 both were perceived within the African American community as "the best there was for a new kind of singer for Black women...showing that Black women were not just blues singers" (p. 79). Holiday named Fitzgerald as her favorite singer in a 1937 interview with Lillian Johnson for the Baltimore Afro-American. Fitzgerald, for her part, "idolized Billie and her songs. She was the first really modern singer to my way of thinking. We all wanted to be like her." To be sure, Holiday and Fitzgerald participated in battles-of-the-band during the big band swing era, but there was mutual admiration off the bandstand.

The binary opposition between them, which continued well into the 1990s and threw into question Fitzgerald's bona fides as a true jazz singer, originated among mainstream jazz critics (virtually all men, largely white). Unsurprisingly, part of it concerned sex appeal; Holiday's voice had a "sexuality" (Donald Clarke, "Billie Holiday," Oxford Music Online, 2012) while Fitzgerald remained a "little girl" in the eyes and ears of Nat Hentoff ("Ella Fitzgerald: The Criterion of Innocence for Popular Singers," 1959). And in a 1994 New York Times book review entitled "One Scats, the Other Doesn't: New Biographies of Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday Examine Their Very Different Styles and Stories," Francis Davis writes that "It is virtually impossible to listen to one without also hearing the other; they seem to demand that we make a choice."

The question of "room to cover two singers" reflects the roles and status of women and singers in jazz and elsewhere in the 20th century. As Tick explains, "The most prominent female vocalists could and did exemplify the 'modern woman,' paralleling the empowering competence that was lighting up the screens in Hollywood's screwball comedies. But beyond their star personas, female singers, in the realities of the profession, endured low pay, low professional status, and low musical autonomy" (p. 78). Writers in Downbeat and Metronome, for example, referred to them as "decorative furniture" in articles with such titles as "Why Women Musicians Are Inferior" and "The Gal Yippers Have No Place in Our Jazz Bands." (Well, maybe space enough for just one.)

Fitzgerald was dismissed by some reviewers as "jazz-pop." In 1938, "A-Tisket, A-Tasket" may have ejected her from the jazz canon as far as Schuller was concerned but Tick's research shows that, in the 1940s, "Along with Billie Holiday and other singers, she was bringing the musical language of jazz to songs from Broadway, Tin Pan Alley, and the blues tradition, before any notion of 'jazz-pop' had entered into common parlance" (p. 123). Fitzgerald developed performance practices that reflected her reception among Black audiences across the US, before she crossed into the white mainstream. These were in harmony with what "the people," as she referred to her audiences, responded to. It took some jazz writers a bit longer to catch on. In a 1942 review in Metronome, George T. Simon disparaged an improvised second-chorus melody, commenting that "Ella Fitzgerald sings a swell straight chorus of 'The One I Love,' but then gets too tricky for her own good" (p. 124). Today, a second-chorus improvisation with lyrics is de rigueur in Great American Songbook type jazz singing.

We all know that Fitzgerald did not stop at pop. It was a "transformative moment for vocal jazz" when, in 1947, Fitzgerald's first bebop sides, "Lady Be Good" and "Flying Home," were released on Decca (YouTube, bottom of this page). Paying no heed to bop's detractors—prominent musicians and commentators alike—Fitzgerald aligned herself with Dizzy Gillespie and the "serious modernist movement that demanded a profound rethinking of jazz's traditional relationship to popular music" (p. 149). Her bebop sides showed Fitzgerald creating space for herself in the jazz pantheon through scat solos with signifying quotations woven into them (some references obvious, others more subtle). Reception for Fitzgerald's new style was mixed. Downbeat gave her 1947 "How High the Moon" improvisation four stars, but Metronome graded it "B-minus," with the reviewer complaining that "The biggest vocal talent of our time is both disappointing and brilliant on 'Moon.' Ella goes wrong in singing some cheap, coined lyrics" (p. 165). Tick counters that "Jazz critics could not always appreciate how much she grew as an artist precisely from her awareness of the needs of an audience," something she conveyed with phrases like "I'm singing it because you asked for it; I'm swinging it just for you."

Into the 1950s, Fitzgerald built a career on recording hit singles, touring in Black theaters and—beginning in 1947—joining her instrumentalist peers as the lone singer and woman in producer Norman Granz's Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP) all-star jazz revues. JATP shows were traveling jam sessions, and the spirit was often competitive. Fitzgerald traded fours (and whatever else) with the men each night during the grand finale. An amusing anecdote recounted by Oscar Peterson revealed that she was not the "little girl" some imagined. "I told you about getting too sporty out there with Lady Fitz, Pres [Lester Young] reminded Flip Phillips one night when he decided to stay at the mike and 'fairground' as Pres put it. 'Geez,' muttered Flip in disbelief, 'I didn't think she'd get that rough.' 'Rough?' repeated Pres in sarcasm. 'You stay out there long enough and Lady Fitz will really lay waste to your ass! Lester knows better. Lester lets Lady Fitz sing her little four-bar song, then Lester plays his four-bar song, and then Goodnight Irene. Lester's through'" (p. 204)!

In 1956, Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook, which Granz produced for Verve, was another turning point, with sales over 100,000 within the first month of its release. She developed a different approach for the project, singing the melody quite simply, intentionally throwing the spotlight on the songwriter and—at Granz's suggestion—including the introductory verse. Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Rodgers and Hart Song Book (Verve, 1956) was even more successful than the Porter album. So began the songbook series that came, arguably, to define our notion of the Great American Songbook, another leg of Fitzgerald's journey. Becoming Ella Fitzgerald covers the wide and long territory of Fitzgerald's career, digging into the music, getting behind the public persona, filling gaps and correcting misconceptions to present a fuller picture of the life and work of "Queen Ella." It is essential reading for jazz aficionados.

< Previous

Kevin Sun: Emotion, Technique, and th...

Next >

Shadow

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.