Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Mostly Other People Do the Killing: Setting the Record Straight

Mostly Other People Do the Killing: Setting the Record Straight

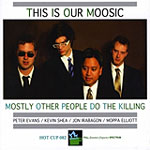

The quartet's rebellious spirit and wry sensibility is deeply rooted and readily apparent, well beyond its name. Released exclusively on Elliott's Hot Cup Records imprint, the band's four previous studio recordings offer a maniacally post-modern take on the tradition, willfully embracing the DIY punk aesthetic to "kill yr idols." Reinforcing this attitude, its album covers have repeatedly parodied iconic jazz sessions from the past: 2007's Shamokin!!! recasts the bold typeface design of drummer Art Blakey's A Night in Tunisia (Blue Note, 1960); 2008's This Is Our Moosic restages the group portrait of saxophonist Ornette Coleman's This Is Our Music (Atlantic, 1960); and 2010's Forty Fort sends up the pastoral scenery of drummer Roy Haynes' Out of the Afternoon (Impulse!, 1962); while its sole live release for Clean Feed Records, 2011's The Coimbra Concert, emulates the stark chiaroscuro of pianist Keith Jarrett's The Köln Concert (ECM, 1975).

Despite the high-brow tomfoolery, the group boasts a truly phenomenal cast, whose quicksilver interplay has been perfected by years spent together on the road. Trumpeter Peter Evans and saxophonist Jon Irabagon, 2008 winner of the Thelonious Monk Saxophone Competition, make a wickedly capricious frontline, while Elliott and drummer Kevin Shea form an elastically resilient rhythm section. Evans' staggering instrumental virtuosity and affinity for experimental extended techniques is paralleled by Irabagon's chameleonic delivery; together they seamlessly juxtapose circular breathing motifs, multiphonic outbursts and vocalized textures with contrapuntal harmonies, minimalist refrains and familiar quotes, referencing the entire jazz continuum all at once. Playing both in and out of time, Elliott and Shea further amplify this maximalist aesthetic, with the leader's robust bass lines underscoring Shea's ramshackle trap set deconstructions at every turn. Heading into previously uncharted territory, Slippery Rock! is the self-described "terrorist bebop" band's fifth studio recording.

|  |  |  |

All About Jazz: Almost all of Mostly Other People Do the Killing's (MOPDtK) album covers (other than its self-titled 2004 debut) mimic the appearance a classic jazz title, yet the newest release, Slippery Rock!, does not, instead parodying a tacky, fluorescent-colored 1980s vinyl record jacket. Why the change?

Moppa Elliott: Well, there was no specific album I wanted to parody for this one, so we did a parody of an entire era. The idea was in part inspired by the colored suits that graphic designer Nathan Kuruna found at Target...

AAJ: Although Slippery Rock! is purportedly inspired by "smooth jazz," it sounds as strong and uncompromising as the rest of the group's oeuvre. When interviewed by Kurt Gottschalk in the spring 2011 issue of Signal To Noise, there was mention that these new pieces were first premiered live using keyboards and electric bass. Can you elaborate on how the tunes changed from inception to recording?

ME: I originally thought that the keyboards and electric bass idea would lead to some new musical material for us, but instead it was a barrier. Peter felt most strongly about this, but after we talked about it for a while, I came around and agreed that the interaction between the four of us can continue to grow and develop without changing instruments or having Jon and Peter play keyboards. I wrote the original versions of most of the tunes on Slippery Rock! with that instrumentation in mind, then rewrote them for the original instrumentation. I found that very little changed when I took out the keyboard parts and that the stronger tunes worked in both contexts. There were a few that I wound up cutting since they didn't work without the keyboards or I just wound up not liking them.

AAJ: Most of the new numbers are aesthetically consistent with previous efforts, yet there are definitely a few that break from convention. The slinky ballad "President Polk" unfolds with piccolo trumpet and sopranino saxophone soaring high over a sinuous groove, emulating (according to the press release) the erotic R&B of artists like Prince and R. Kelly. The conceptual touchstones for that track are fairly obvious, but perhaps you can illuminate some of the album's more obscure references, such as the Chris Botti and Kenny G elements that are supposedly part of the opening cut, "Hearts Content" or the driving melodicism that underscores the tuneful closer "Is Granny Spry"?

ME: I bought about 30 smooth jazz albums and immersed myself in that sound world for a while (that sounds hilarious to say). So the R. Kelly tune is the most obvious, but all the tunes are an attempt to write in the idiom, but without specific references. I listened to a lot of Kenny G, Chris Botti, Dave Koz, Najee, David Sanborn, Grover Washington, Jr., etc., and tried to write the kinds of songs they wrote, just like I usually do for '50s and '60s-style jazz on the previous albums. I think that finding the "obscure references" in our music is like an Easter egg hunt for the listener in which the harder you look, the more you'll find. I'm surprised to hear that the last tune has "driving melodicism," but that's cool. I also think that when a composer or musician tries to explain their music by telling a story about what it "means" that it takes away from the music. I could tell any weird story I want right now about what "Is Granny Spry" is about, and some of it might be true, and some of it might provide some insight into "how I compose" but none of it would make the recording sound any different in a fundamental way... it would just be playing with listeners' subjectivity. That was the whole point of naming the songs after towns in Pennsylvania... that way I can completely avoid the subject of what the songs are "about." That might be escapist or pretentious, but I like it. Honestly, does me telling you that "Sayre" was inspired by a lick that Gerald Albright plays tell you more about the music than the fact that I am related to the Sayre family? Either way, the tune sounds the way it sounds and different listeners will hear different things.

Jon Irabagon: I just wanted to add that from my perspective, it's been interesting using the groove/funk/smooth jazz material and reference points as a home base as opposed to the departure material. In the entire history of the band so far, various eras of swing and more traditional jazz have been the starting points, and the members of the band allow (or don't allow) themselves to reference other genres or eras. However, with Moppa's writing on Slippery Rock!, the home base now is the former departure material. It has been both a challenge and insightful into my own playing/improvising/point of view to flip the script.

Peter Evans: As a trumpet player there are a lot fewer reference points for me in the music you mention than for the other guys. There's not too much trumpet in a soloistic context in pop-jazz after the 70's other than the obvious reference points, like Miles Davis' '80s work and subsequent clones of that type of Harmon mute-with-reverb thing. Then there's the more recent stuff like Rick Braun and Chris Botti. But I certainly don't feel I can do much of anything on the trumpet that will immediately "dial in" a reference to erotic R&B the way the rhythm section instruments or the saxophone can. I feel in this newer set of music my role is mainly some sort of running commentary from outside the music-material universe we're dealing with. I'm not really a fan of smooth jazz trumpet other than as an economic and cultural curiosity, so there's not too much of a reason I would reference it. I played a Harmon mute-with-reverb solo on "East Orwell" from This is Our Moosic and told Moppa that's the only solo like that he's going to get from me, ha ha.

AAJ: Considering the band's debt to the all-inclusive, post-modern jazz continuum initiated by such artists as Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Charles Mingus, do you ever worry that the quartet's perceived reliance on humor might overshadow the individual members' merit as innovators, or do you see a parallel with movements/scenes like New Dutch Swing?

ME: I don't think we rely on humor at all. There is certainly levity and humor in our music, but a lot of that is based on the listener's knowledge and perspective. I don't think a listener completely unaware of jazz and improvised music (i.e., a Justin Bieber fan) would find any humor in our music at all. We think certain things are funny, and some people think those same things are funny, and other people don't. I think the music is strong enough and complex enough and interesting enough to be captivating to people on a variety of levels, and hope that no one is simply listening to our music to find "jokes." Juxtaposition can produce humorous effects (check out Whose Line Is It Anyway), but it can also produce collage and abstraction. The Dutch were and are a big influence on us, but their humor is a bit different. Willem Breuker can be "silly" in a way we rarely are, as can Han Bennink, but we have a different perspective because of our childhoods and education. Not as much '80s pop with them...

JI: As Moppa said, humor (in this case) relies on a person's references and what they might view as "normal" or "acceptable" in a jazz performance. A jazz musician not familiar with the Dutch history would find something that, say, Kevin might do completely weird, unnatural, or "incorrect." But even a layman that has investigated that type of music or performance art or something of the sort could see that some of his actions may be part of a continuum of thought, or an extension of a philosophy behind music or performance. The said jazz musician would simply dismiss this as humoristic, but the person with the wider view on what art can or should be wouldn't find it funny.

PE: I agree with a lot of what the other guys have said—humor, like a lot of things, is just a matter of perspective. I have definitely been frustrated by all the talk of our music being "funny." Humor, or why something is funny, is a notoriously hard thing to talk about so I won't try to define our band's sense of humor or why we think playing "All Things You Are" like comatose West Coast Jazz guys for 15 minutes without variation is compelling to us. It seems like part of what you are referring to is deeply related to our collage approach; the humor for us and for a lot of people has to do with the juxtaposition of unexpected elements.

Juxtaposition isn't necessarily meant to be "funny," and it has broader roots than just comedy. In the case of music by Jaki Byard or the Art Ensemble Of Chicago, it seems to me that part of the idea was to articulate a continuum of Black music—in other words, elements are thrown into collision with one another because they belong together, not because they don't. I feel that way about the Don Pullen/George Adams music as well. And all this stuff had been hugely influential on me and I suspect other guys in the band, although I wouldn't say that's how we always conceive of juxtaposition. We are coming from a much different place. I always cringe a little when the Dutch scene is brought up as if it's a uniform club of musicians all doing the same thing, i.e., a movement. Kevin Whitehead's book is very detailed in its attempts to distinguish the different musicians and their histories. A collage-type of approach is talked about quite a bit though, and I think it's this aspect that leads people to think music by ICP Orchestra or Clusone Trio or the Ab Baars trio is "funny."

What bothers me is how this often equals "insincere" for people. A classic example of juxtaposition or collage playing is My Name Is Albert Ayler (Black Lion, 1963), the Albert Ayler live session with the Danish rhythm section (Ab and a few other musicians cite this as an influence in New Dutch Swing), and it's definitely something to think about. Ok, from a traditional standpoint it "doesn't work"; the rhythm section can't meet Ayler even halfway and there is a profound disconnect. From an "artist intention" point of view, it's a failure. From a more sound-object oriented way of listening, it's great. At least I think so. For me the importance of the advances made in collage based or high-risk juxtaposition improvisation from all the people I mention above is that they have helped reclaim these kinds of structures as things that can be intentionally worked with and deliberately employed to create new music. It requires that everyone is on the same page and understands (as Jon talked about) that ignoring everyone else and playing something totally contradictory to the other three guys actually serves a larger purpose in opening up the large scale structure and sound-world of the music. And yes, it can also be funny.

AAJ: Although founded in 2003, the unit's roots can be traced back to the late 1990s, when you and Peter Evans studied together at Oberlin. Moppa, how do you manage to maintain the ensemble's collective identity, while still serving as its primary composer and leader?

ME: MOPDtK's origin is in 2003, since the quartet is dependent on all four members for its identity. Peter and I had some fun precursor bands in school, but nothing like what MOPDtK was or has become. The collective identity IS the group, so I don't need to manage it in any way... actually, I'm not sure I understand this question. I write tunes for us to play, but we never play what I wrote exactly anyway. I pick the set list, but sometimes get overruled within the first measure. I count the tunes off, but that tempo might not ever actually happen. So I'm not really sure what I manage to maintain. I guess as the bandleader I have to deal with hotels and interviews and logistics and setting things up, most of which involves sending emails, not exactly an artistic expression.

AAJ: In a similar vein, how does each of the band member's different personalities and stylistic predilections influence your writing?

ME: Ah... well, I learned pretty early on that if I write anything that I want to be executed exactly, I'm in the wrong band. I take for granted that nothing I write will ever be played as written, but all of the elements will be used... so I try to write simple melodies and harmonies and forms, so that the tunes can be broken up into recognizable pieces and rearranged. I assume that Kevin will never play straight time, except when we least expect it, that Peter will ignore the melody from time to time and launch into screechy or farty noises, and that Jon will pretend to play what's written but change harmonies, articulations and timbres constantly. Oh, and I will usually play the root, but not always.

AAJ: What are your thoughts on studio recording versus live performance and how does that affect your playing in each situation.

ME: Both are very different. On this last recording we were all in the same room, which helped create a little of the energy we have playing live, but every situation is different. In the studio, there are obvious barriers between the musicians, which tend to make studio recordings more risk-averse, but in live situations the sound can be just as challenging. Sometimes we can hear each other really well, and sometimes not, and we've all learned how to perform with this group in pretty much any context. Each environment will alter the music in major ways, but we try to find a way to make any situation we are in work.

JI: The collage pieces that we play live don't work in the studio, especially when we are trying to get new material down. However, the other elements that MOPDtK use regularly are still in play, like genre-shifting, sabotage, or insertion of standards, pop or classical songs.

PE: Part of it is the classic problem of atmosphere, energy and hard-to-define things that differentiate playing in a silent box from playing in a crowded room with people we don't know. We have never been a band that's rehearsed much so by default most of our time playing together is in performance. It takes some effort to get used to the studio vibe and for whatever reasons we seem to play better in short, focused bursts rather than sprawling collages. In a performance the time limits of the pieces are often felt/determined by the set length, whereas in the studio we are often looking at four or six hour oceans of time. It doesn't help us much in terms of concision.

AAJ: Recalling MOPDtK's dynamic live performances, Kevin is the most explicitly absurd (an heir apparent to Han Bennink, even), Peter is the most subtly subversive, while you and Jon tend to fall somewhere in-between. Despite the comedy, your roles are obviously incredibly technically demanding, as demonstrated by kaleidoscopic juxtapositions of multiple tunes. Can you explain the basic parameters of that collage-oriented concept?

ME: Well, there are about 40 tunes of mine in our repertoire, and any of them is fair game at any time. That being said, I think we all get a lot of satisfaction out of playing very cohesive music sometimes and very chaotic music other times. We do that by listening to each other and maintaining awareness of what everyone else is doing. Frequently someone will try to cue one of the tunes and no one will go with them, which is fun, so we all have to have faith that each person can make something cool happen on their own, even if they are abandoned by the rest of the group... that happens a lot. There are also a ton of standards that show up in our sets, some of which are arrangements we have and others are spontaneous. Since we all listen to a lot of the same music, we can choose to go with someone or against them when they reference a specific composition, mine or otherwise.

Kevin Shea: I want to respond to the Han Bennink reference. I love Han Bennink... however, it seems whenever a drummer does something "theatrical" in a jazz environment they are accused of being an heir to Han Bennink. As a kid, before I even knew who Han Bennink was, I was going to Motley Crüe concerts—Tommy Lee had a drum set on a platform that would float out over the audience and then turn upside down during his power rock drum solo. Tommy Lee would also bungee jump off of his drum platform into the audience. That was far more "explicitly absurd" than anything I have ever seen Han Bennink do. I was also a fan of Samuel Beckett's plays growing up, and his "explicitly absurd" choreography has been far more inspiring to me than Han Bennink. In addition, before ever knowing of Han Bennink, I was performing compositions like John Cage's Theater Pieces—succumbing to theatrical consequences that may have often appeared "explicitly absurd," but were in fact to me very compassionate, without intention, and ZEN.

When I finally learned of Han Bennink, I had already been doing "explicitly absurd" theatrics based on a variety of influences—Han Bennink seemed normal to me. Other drummers don't hump stage monitors and do headstands on bass drums because they are too intimidated by their context and have absolutely zero background researching, investigating and participating in the broader spectrum of modern art... their close-minded, god-fearing educators should be fired—for, little do they know, they are in practice perpetuating a student-base unconsciously indoctrinated with not only a lack of compassion but a deep disgust for diversity—these are the beloved tenets of warmongers, and everything I protest against as a drummer, artist, human. In any case, I love me some Han Bennink.

AAJ: As a related follow-up, although individual solos are part of the group's aesthetic, collective improvisation is even more predominant, especially in regards to the frontline's thorny interplay. Can Jon and/or Peter elaborate on their alternately complementary and contrasting approaches?

JI: The main goal in this ensemble for me during the improvisation is to keep things moving forward, never letting things settle (unless that's a temporary proactive choice). Further, I'm not necessarily into the idea that a solo or improvisation has to make a consistent linear line, definitely not all of the time. So choosing to jump in, in the middle of one of Peter's ideas, or laying out for an excessively long time when it might make sense to join in, is an attempt to keep shifting the flow of a piece. Sometimes it works out really well, and sometimes it creates a hole that we (or I) have to dig myself out of. But that kind of tension/weirdness is supported, accepted and sometimes looked for in this band.

AAJ: A common complaint about post-modern music is the potential for eclectic artists to lack a consistently recognizable sound (tone, phrasing, etc.). Although sonically fascinating, do you ever worry that so many schizophrenic shifts in mood, style and technique could be counterproductive to developing a distinctive voice on your respective instruments, or do you see such approaches as their own means to an end?

ME: I completely disagree with the premise of the question. I think that a musician's "distinctive voice" is easier to hear in a wider variety of circumstances... you can hear the same musician from different perspectives. I think that the way in which a musician navigates the changes of mood and feeling, however rapidly, exposes more of their inner thinking about music than only performing in controlled situations does. If we are lucky enough to have "distinctive voices," and I think we do, it is because we are able to expose so many of our influences and move beyond them. Every musician is just a walking collection of influences and exercises, and we have all tried to use elements from as many sources as possible, so our voices emerge as personal edits of all the music we have heard and played. A lot of jazz musicians are limited by their education and narrow musical world view, and I think that makes a distinctive voice more difficult to come by... I mean, come on, how many indistinguishable jazz tenor saxophonists are there?

JI: I completely agree with Moppa on this.

PE: I actually do think that the growing trend of musicians trying to "be able to do anything" poses some real problems along the lines you are referring to. I find myself less and less concerned with this as time goes by (I think I felt pressure to be able to "do anything" as I was leaving music school), and although I still play in a fairly broad range of situations, I'm more interested in cultivating and developing something (a voice? a sound?) that's flexible and adaptable (very important if I plan to continue improvising) while at the same time allowing me to feel like I'm being myself. It's hard for some people to believe but navigating through a variety of material in one piece actually feels very natural for me and I don't have to "step outside of myself" in order to oscillate between diatonic melodic shapes and white noise on the changes to "Misty."

Sometimes I do think about multiple perspectives or narrator voices (like shifting between first person narration and an omniscient 3rd person) as a way to access the material in different ways. This stuff crosses my mind not while playing but more when just reflecting on why certain things feel natural to me and why others don't. I recently watched John Butcher play a solo concert and it really blew my mind—he worked with a much narrower range of materials than I was expecting and somehow instead of presenting an encyclopedic range of saxophone sounds in the course of his pieces, he presented some kind of metaphorical representation of that same thing. This kind of "deepening" rather than "broadening" approach appeals to me very much. I know I'm not explaining this idea of instrumental performance as a metaphor very well... still working on it.

AAJ: Jon, you've just launched your own label, Irabagast Records with two very different inaugural releases: Unhinged, the sophomore effort from your newly revamped Outright! Quintet, following the group's 2008 self-titled debut for Innova Records); and I Don't Hear Nothin' But The Blues Volume 2: Appalachian Haze, the visceral follow-up to your powerhouse duet with drummer Mike Pride, I Don't Hear Nothin' But The Blues (Loyal Label, 2009). Considering Moppa has run Hot Cup Records since 2001 and Peter founded his own imprint, More Is More Records in 2011, did you derive any wisdom from them on how to run a label?

JI: Yes, I've asked them for a lot advice and just a general view on what that whole world is like. It's a completely different thing than trying to get gigs or working on music, and the only way to figure that stuff out is to go through it, though having people around who have done this same type of thing definitely helps.

AAJ: As label proprietors, what are your thoughts on the state of the recording industry at large, especially in regards to archival hard copies versus ephemeral downloads?

ME: I really like the idea of music contained in an object. The idea of "collecting" appeals to me and others, and even as files replace CDs in the marketplace, vinyl is making a comeback, and I think there will always be certain people who want to collect music as an object. That duality (object/vibration in air) has been around since notation began, and I think that objects will be around for the foreseeable future, just not as the primary drivers of the music economy. As archival devices, everything but vinyl is pretty temporary, and even that has a couple of centuries, max, so as technology changes, so does the archival strategy.

In a certain sense, MP3 files are just as archival as LPs or CDs; they are storage mechanisms for a thing that exists really only as vibrations in air. The challenge for the recording industry and for us is to continue to find ways to make money making music. If the sales of recordings are no longer enough to sustain a career, other revenue streams need to be explored, and the live performance is still the most consistent for us... it's really only The Beatles that can get away with never performing, and they were already retired road warriors when they stepped off stage...

JI: I think one of the advantages to running a smaller label is that you aren't dealing with the sheer numbers that a huge label deals with. You can be (and have to be) smarter about the budget, etc. because it's most likely your money that's going into the product, not some company's. There will always be people out there that want to have a physical copy of a record, and you can cater to them by having just a few hundred or a thousand or so copies of your record to sell at shows or over the internet. I think that the duality of having both physical and digital music available is a good thing as different people like receiving and listening to their music in different ways. So far, I've sold just as many physical copies of my new records as downloads, so I wouldn't be too quick to pull the plug on a physical product as of yet.

PE: I've only put out one thing and it sold out, although there were only 1000 copies. We're on a very small scale. I have two things coming out soon so it will be interesting to compare. I really like listening to recorded music and I still buy and listen to a lot of it, so I'm making records partly to generate work but also just because I really like making and listening to records. Commercially available recorded music has been around for only 100 years but people act like it's a naturally occurring phenomenon and can't believe it's going away. It was nice while it lasted, but obviously things are changing. Unfortunately the systems surrounding the recording/music industry (studios, recording equipment, booking agencies, music magazines) still exist and seems fairly intact—which makes it hard to figure out how to work if you don't put out records!

KS: I don't have a record label, but I want to chime in. Record labels should stop releasing the CD/LP formats, and instead offer objects that people can actually use in real life with download codes. In my opinion, there is no reason why there shouldn't be a MOPDtK line of socks or totebags or t-shirts with download codes sewn in them. For the people who want to pay more, they could get a rake with a download code. If I ever start a label, my idea is to have one copy of my release available... it will be a download code tattooed on a pig somewhere on a farm in eastern Slovakia. The person who wants to hear the record will have to go on a quest to find this pig in order to hear my label's release. Labels need to be more creative with their merch, and by doing so they will inspire consumers to think differently about the nature of their hollow desires. I'd rather inspire a person to be a consumer and a member of society, rather than just a consumer isolated with a record in their den. Put a download code on some sunglasses, encourage a person to go outside...

AAJ: And finally, beyond jazz, are there any contemporary non-jazz based artists you find inspiration in?

ME: El-P, Mastodon, R. Kelly, Punch Brothers, The Neptunes, MF Doom, Ludacris, Meshuggah, Janelle Monae.

PE: Right now: Gene Rodenberry, Anton Webern, David Foster Wallace.

KS: Composer Jonathan Harvey died recently... I've been having a hilarious time listening to his piece "Wagner Dream" (Cypress). Also I've been enjoying the piece "Dienstag Aus Licht" by Stockhausen (CD number two from Karlheinz Stockhausen's album, Dienstag Aus Licht Vol. 40). It looks like it was a totally nuts production/staging as outlined in the extensive liner notes.

Selected Discography

Mostly Other People Do the Killing Slippery Rock! (Hot Cup, 2013)

Mostly Other People Do the Killing, The Coimbra Concert (Clean Feed, 2011)

Mostly Other People Do the Killing, Forty Fort (Hot Cup, 2010)

Mostly Other People Do the Killing, This Is Our Moosic (Hot Cup, 2008)

Mostly Other People Do the Killing, Shamokin!!! (Hot Cup, 2007)

Mostly Other People Do the Killing, Mostly Other People Do the Killing (Hot Cup, 2005)

Tags

Mostly Other People Do the Killing

Interview

Troy Collins

Braithwaite & Katz Communications

United States

Moppa Elliott

Art Blakey

Ornette Coleman

Roy Haynes

Keith Jarrett

Peter Evans

Jon Irabagon

Kevin Shea

Chris Botti

Kenny G

Dave Koz

Najee

David Sanborn

Grover Washington Jr.

Gerald Albright

Miles Davis

Rick Braun

Rahsaan Roland Kirk

Charles Mingus

Willem Breuker

Han Bennink

Jaki Byard

Art Ensemble of Chicago

Don Pullen

George Adams

ICP Orchestra

Clusone 3

Ab Baars

Albert Ayler

John Cage

John Butcher

The Beatles

About Mostly Other People Do the Killing

Instrument: Band / ensemble / orchestra

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.