Home » Jazz Articles » Film Review » Icons Among Us: Jazz in the Present Tense - Episode Four...

Icons Among Us: Jazz in the Present Tense - Episode Four: Everything Everywhere

Icons Among Us: Jazz in the Present Tense

Episode Four: Everything Everywhere

The Documentary Channel

May 11, 2009, 09:00-10:00PM

Paradigm Studio

2009

Icons Among Us: Jazz in the Present Tense, the weekly television series that's been airing on The Documentary Channel in the US since April 20, 2009, comes to a close with Episode Four: Everything Everywhere—a sweeping statement that addresses both the undeniable African-American roots of jazz and the music's expansion into places farther abroad.

The show opens at Congo Square in New Orleans where, according to drummer Stanton Moore, "the slaves were allowed to play their indigenous African music—and that happened on Sundays, pre-Civil War," even when drums were banned in the American south. That this music became the root of so many musical genres—jazz, of course, but also R&B, funk, blues, rock and roll, hip hop and more—by hybridizing the melting pot of influences including clave, African and marching rhythms, is made crystal clear. Jazz has become many things, but there's no doubt that it began in New Orleans, and that Congo Square was Ground Zero. Saxophonist Donald Harrison, who's featured throughout the episode, puts it succinctly: "I know what I have to do from listening to the beat and hearing all the signals."

![]()

If Icons Among Us has represented one thing, it's this: jazz may have begun as an American art form, based in the roots of New Orleans, but it's evolving into something much more. Rather than being a music that excludes, it's a music that includes. Matters of race, culture, geography, gender, religion...none of these things matter in a music that's become global—and has been doing so practically since its inception. British saxophonist Courtney Pine talks about his own music, that's made the journey from Africa to the Caribbean to the United Kingdom. Footage of a Pine concert dedicated to Sidney Bechet crosses multiple boundaries to suggest not just what Bechet was, but what he might have become were he alive today.

The episode is clear about the still present myopic view of jazz. Pianist Robert Glasper is, surprisingly, a member of that contingent: "There's a whole movement of cats from Europe that play jazz," he says,"but there's a key thing missing in most of it when I hear it, 'cause—not putting Europe down out there—they're classically based. It's a classically trained thing and jazz isn't based on classical music, it's based on blues and church and emotion and spirit—the real shit. So you can play all the shit you want, but if you don't have none of that...," with the editors astutely leaving out the obvious conclusion. All this spoken while the Dutch trio of saxophonist Tineke Postma, bassist Ernst Glerum and drummer Han Bennink—a legend in his own right—prove that taking the music of classical composer Villa Lobos and using it as a jumping off point for improvisation can be as swinging, emotional and spirited as anything Glasper refers to.

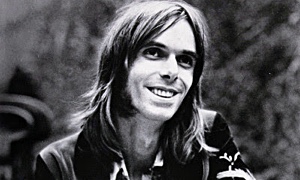

![]() The good news is that Glasper's view is in the minority, at least across the broad range of musicians interviewed for this episode, ranging from guitarist Charlie Hunter, trumpeter Terence Blanchard and singer Jamie Cullum to pianist Herbie Hancock and saxophonist Wayne Shorter. Norwegian keyboardist Bugge Wesseltoft (pictured) has, perhaps, the most balanced view of how jazz has become a music that belongs to the whole world. "There is a difference," Wesseltoft reflects. "American jazz music is based on the African-American tradition, it has a black feel to it, which is different to the European beat, which has more of a whitish, classical touch."

The good news is that Glasper's view is in the minority, at least across the broad range of musicians interviewed for this episode, ranging from guitarist Charlie Hunter, trumpeter Terence Blanchard and singer Jamie Cullum to pianist Herbie Hancock and saxophonist Wayne Shorter. Norwegian keyboardist Bugge Wesseltoft (pictured) has, perhaps, the most balanced view of how jazz has become a music that belongs to the whole world. "There is a difference," Wesseltoft reflects. "American jazz music is based on the African-American tradition, it has a black feel to it, which is different to the European beat, which has more of a whitish, classical touch."

With a performance of trumpeter Roy Hargrove's quintet onscreen, Wesselfoft continues: "Sometimes I wished I was African-American; I always wanted to be, 'Why didn't I grow up in the Bronx?' Then, at some stage, I realized that if I am to manage to do something which is strong for me, I have to find my own source, find my own spirit. I ended up listening to a lot of Norwegian traditional music, to Europe art music and I try to bring in those elements towards the improvised music and, of course, the jazz background that came from childhood—jazz I've been listening to—I'm still trying to have a mixture of those things."

Jamie Cullum suggests the Wesseltoft should be an international star with his remarkable ability to mix contemporary beats and more with a clear reverence for jazz history. It's a fair statement. As a solo performance of Wesseltoft doing just that is featured, the Norwegian continues: "You can't separate things and say 'this is exclusively our art form,' because for thousands of years there's been communication throughout the world and everything sticks together and mixes. I love that with jazz music, it's been able to bring in new elements and once you mix two cultures together something new comes out." Wesseltoft's view that jazz is a living, breathing, growing thing that continues to assimilate new sources is echoed by saxophonist Miguel Zenon: "I think that all this stuff is kind of mixing together, really almost without people realizing it. You hear everything everywhere; this stuff is really seamless, it's already a part of it and people don't really realize when it happened."

So clearly it's a sentiment shared across numerous boundaries, rendering the more reductionist views of artists like Glasper as almost irrelevant, if not still slightly disturbing.

![]() The episode's second half returns to post-Katrina New Orleans, where Blanchard articulates just how vital jazz is to the lifeblood of so many people there. At the first New Orleans Jazz Festival after hurricane Katrina, Blanchard describes how it was "a beautiful thing to see. All the musicians made a statement: 'Look, we're not goin' anywhere. This is who we are and this is who we wanna be and it's gonna remain that way.'" As the episode moves to the issue of jazz education and how, even as early as the 1960s, drummer Art Blakey said "it's very clinical nowadays," it shows hope for the future of jazz, with the importance of mentoring returning, with musicians like Blanchard and saxophonist Donald Harrison Jr. (pictured) teaching young students. Harrison teaches teenagers at the Tipitina Internship Program, where footage from a class proves that it's as much about feel as it is technique, something oftentimes being lost in the larger institutions.

The episode's second half returns to post-Katrina New Orleans, where Blanchard articulates just how vital jazz is to the lifeblood of so many people there. At the first New Orleans Jazz Festival after hurricane Katrina, Blanchard describes how it was "a beautiful thing to see. All the musicians made a statement: 'Look, we're not goin' anywhere. This is who we are and this is who we wanna be and it's gonna remain that way.'" As the episode moves to the issue of jazz education and how, even as early as the 1960s, drummer Art Blakey said "it's very clinical nowadays," it shows hope for the future of jazz, with the importance of mentoring returning, with musicians like Blanchard and saxophonist Donald Harrison Jr. (pictured) teaching young students. Harrison teaches teenagers at the Tipitina Internship Program, where footage from a class proves that it's as much about feel as it is technique, something oftentimes being lost in the larger institutions.

And mentorship means that education isn't always restricted or best served in the classroom. Roger Lewis, of the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, talks of how the band has members ranging from 20 to 60, and now "it's my duty, as a senior member, since I have all this experience, to give them some of my experience, pass it on to them."

But even New Orleans, the Ground Zero of jazz, is opening up to broader ideas. Footage of 8-string guitarist Charlie Hunter is, in itself, remarkable, but not just for his trio's performance. He's playing in Preservation Hall where, only a few years ago, guitars weren't allowed, let alone 8-string hybrid electric ones. The idea that jazz continues to evolve and assimilate is not lost on artists like Blanchard either, who teaches his students to "Let go and trust your training. Let the music guide you. The music is not about you, it's about the music; make it about the moment."

Even Herbie Hancock sees the change in the music, and that, despite jazz's seemingly small profile—especially in the United States—there's still plenty happening. "A lot of young people are very interested in jazz. It may not seem like that, from the standpoint of the media, because they don't point their cameras that way. But stuff is happening."

Before the series ends with Donald Harrison repairing his New Orleans home from the ravages of Katrina, and singing with only the accompaniment of a cement pail, Blanchard (pictured below) sums things up with, perhaps, some of its most telling and hopeful words: "It's the most bizarre thing I've come to witness in my life. There's a movement about us with some of the young guys, it's the quietest revolution in jazz that I've ever heard in my life. And it's amazing because they're a group of young musicians who definitely have vision, and the jazz community hasn't caught up to it yet because the jazz community is still trying to be the jazz community of old. The jazz community is not recognizing that things have moved and changed, and we're never, ever going back. So let it go, it's gone."

![]()

With the kind of boundary-busting, genre-defying approach that Icons Among Us: Jazz in the Present Tense has demonstrated throughout its four-week run, jazz finally has a voice that articulates not only what it was, but what it is and what it might become. Without a doubt the best series on jazz that's ever been produced, it's one that doesn't deny the music's deep roots in the African-American tradition; but by including voices from around the world, from different cultures and genders, it posits that it is, indeed, time to dispense with narrow definitions and accept jazz as a music that grows through cross-pollination, assimilation and inclusion. Jazz will continue to evolve, reshape and reinvent itself as long as there are artists looking for new things to bring to the table—and the changes will continue to be documented as long as there are people like series executive producer John W. Comerford and his cohorts at Paradigm Studio. And that's as good as it gets.

Photo Credit

Stills taken from Icons Among Us: Jazz in the Present Tense - Episode Four: Everything Everywhere, courtesy of Paradigm Studio and The Documentary Channel.

Episode One | Episode Two | Episode Three | Episode Four

Tags

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.