Home » Jazz Articles » Profile » Manfred Eicher: Through the Lens

Manfred Eicher: Through the Lens

As a producer, Eicher is a rare entity, an endangered species, in fact, in a time of DIY recordings; he's also unique amongst the vast majority of producers, whose roles are more about ensuring that a recording comes off on-time and on-budget. Eicher makes sure these things happen as well, but his involvement in the music goes beyond mere practical facilitation; he's an active producer, who becomes directly involved in the very creation of the music, from arrangements to track sequencing...even providing the occasional uncredited musical contribution. Originally a double bassist, he rarely plays anymore—though he has been known to pick up a bass, play a little piano or strike a cymbal, every now and then, if it helps him to communicate. Being a musician may not be an absolute prerequisite, but there's little doubt it allows for a common vernacular that's all the more important when mother tongues are, as often as not, different, and when artists from around the world are regularly placed together in new, globe-spanning combinations.

Providing more than just an objective ear, Eicher tacitly but invariably increases the number of musicians in any given ensemble by one, so collaborative is the nature of his involvement. Eicher's strong interest in film leaks into the oftentimes cinematic nature of his productions, and he considers his role more akin to that of a film director. He has even said, to further that analogy, that he views the responsibilities of recording engineers like Jan Erik Kongshaug, James Farber and Gérard de Haro to be the audio equivalent of the director of photography, bringing technical knowledge and trained ears to bear in order to help the director and actors—Eicher and the musicians—more fully realize their vision.

Providing more than just an objective ear, Eicher tacitly but invariably increases the number of musicians in any given ensemble by one, so collaborative is the nature of his involvement. Eicher's strong interest in film leaks into the oftentimes cinematic nature of his productions, and he considers his role more akin to that of a film director. He has even said, to further that analogy, that he views the responsibilities of recording engineers like Jan Erik Kongshaug, James Farber and Gérard de Haro to be the audio equivalent of the director of photography, bringing technical knowledge and trained ears to bear in order to help the director and actors—Eicher and the musicians—more fully realize their vision. Eicher's involvement in the now thousand-plus titles that make up the ECM discography is a defining marker in a life's work that may have begun in the improvised music of pianists Mal Waldron and Paul Bley and saxophonist Marion Brown, but has since expanded to incorporate so many disparate musical styles that the longstanding myth of "the ECM sound" has become even more challenging to nail down. Still, a couple of things are certain: it's almost always possible to identify an ECM production by its sonic transparency and clarity—something many have emulated but never copied precisely; and it's equally possible to tell—if not necessarily judge—an ECM recording by its cover.

As he approaches the age of 70 in 2013, Eicher seems to be doing everything but slowing down; if anything, he's ramped up the pace, a remarkable feat for a label whose employees can almost be counted on the fingers of just two hands, but who have, with Eicher at the helm, helped to maintain the label's reputation for creativity and artistic integrity.

ECM may no longer be the rapid trendsetter it was during the 1970s, when it established a number of canons that have since become the litmus test for others, including a body of solo piano recordings from major artists like Jarrett, Bley and Chick Corea, and relatively new stars including Stefano Bollani, Craig Taborn and Stefano Battaglia. Eicher and ECM also, virtually single-handedly, brought a most remarkable Norwegian scene to international attention, first through seminal artists like saxophonist Jan Garbarek, bassist Arild Andersen, guitarist Terje Rypdal and drummer Jon Christensen, and more recently with emergents on the world stage including saxophonist Trygve Seim, trumpeter Mathias Eick and pianists Jon Balke and Ketil Bjornstad. In today's landscape, it's hard enough to retain an identity, let alone break significant ground and actually have it reach the same number of ears as was the case 30 years ago, but if ECM has felt the tectonic shifts in the music industry, it has remained steadfast in the aesthetic choices that have defined it, while being flexible enough to change where it makes sense to do so.

What Eicher and ECM accomplish, year in and year out, is the relentless expansion of a body of work that remains unparalleled in the history of recorded music, both in size and scope. Sometimes Eicher and his artists succeed in moving things forward in bigger steps, as with Nils Petter Molvaer's Khmer (1997), where techno-informed beats and textures, inextricably linked with the Norwegian trumpeter's inescapable lyricism, became an influential watershed that signaled the beginning of a new wave of Norwegian creativity. There are also times when a project doesn't gain the traction it deserves, as was unfortunately the case with Jon Balke's superb century—and culture-spanning Siwan (2009), an album that should have done better than it did. Still, it remains a high watermark for both Balke and the label—and a clear indicator of Eicher's ongoing commitment to risk-taking, large and small.

As the years have passed, ECM 's refusal to be bound by any genre has continued to define its unique place in recorded music. In any given year (in this case, 2010), the label can be found releasing everything from electro-acoustic improv (Food's Quiet Inlet) and intimate and acoustic jazz standards (Keith Jarrett's long overdue reunion with bassist Charlie Haden, Jasmine) to minimalism-informed Zen funk (Llyrìa, from pianist Nik Bärtsch's Ronin), and a wondrous convergence of the secular and spiritual with Norwegian trumpeter/vocalist Per Jorgensen's collaboration with Finnish pianist Samuli Mikkonen and drummer Markku Ounaskari on Kuára: Psalms and Folk Songs, where the trio's choice of traditional folk material was augmented, at Eicher's impetus, with music stemming from the Russian orthodox church. And that doesn't include the label's New Series, where, in any given year, significant works can be found by composers ranging from the modern (Arvo Part, Erkk-Sven Tüür) and the classical (Joseph Haydn) to the romantic (Robert Schumann).

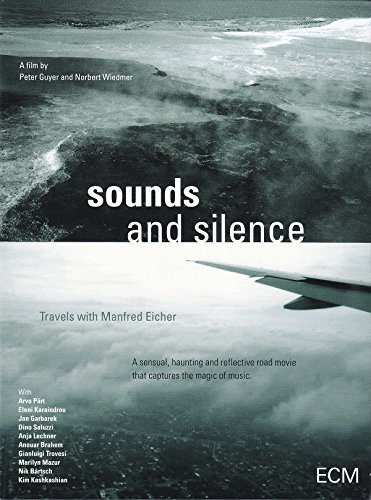

There's only one thing that can tie this all together, and if Sounds and Silence reveals much about Eicher—through glimpses of recording sessions with artists such as Bärtsch, and Argentinean bandoneonist Dino Saluzzi and German cellist Anja Lechner, as well as insightful comments from longtime collaborators like Estonian composer Pärt—it doesn't give it all away. Instead, the 87-minute film successfully treads that fine line between resolving many previously unanswered questions about Eicher—a winner, 40 years on, of numerous awards ranging from the American Grammy Awards to France's Grand Prix du Disque and The Netherlands' Edison Award—and leaving intact some of the mystery that has made Eicher the enigmatic figure he is.

Sounds and Silence relies more on imagery and music (much of it collected on a separately released soundtrack CD, with its own story to tell) than it does spoken word—the subtlest of gestures, sometimes, speak more than any words could. Still, and not surprisingly, every word counts, demonstrating—in direct defiance of those who accuse Eicher of being dictatorial in his control—that the strength of his vision is absolutely predicated on that of the artists with whom he collaborates. Early in the film, during a recording session in an Estonian church, Arvo Pärt speaks about Eicher and a creative process that—in a time when ProTools allows artists to piece together the perfect performance by pasting together the best parts of multiple takes—remains relatively unique. For ECM and its artists, it's not about constructing the perfect take, it's about finding it, about that single uninterrupted performance where, warts and all, the musicians manage to go beyond what's on the written page to create something truly transcendent.

Sounds and Silence relies more on imagery and music (much of it collected on a separately released soundtrack CD, with its own story to tell) than it does spoken word—the subtlest of gestures, sometimes, speak more than any words could. Still, and not surprisingly, every word counts, demonstrating—in direct defiance of those who accuse Eicher of being dictatorial in his control—that the strength of his vision is absolutely predicated on that of the artists with whom he collaborates. Early in the film, during a recording session in an Estonian church, Arvo Pärt speaks about Eicher and a creative process that—in a time when ProTools allows artists to piece together the perfect performance by pasting together the best parts of multiple takes—remains relatively unique. For ECM and its artists, it's not about constructing the perfect take, it's about finding it, about that single uninterrupted performance where, warts and all, the musicians manage to go beyond what's on the written page to create something truly transcendent. After all, perfection sometimes has to be measured in something beyond the tangibly empirical:

We are looking for something very special. Something to do with sound. It's always like this when working with Manfred. Not only must you get the microphones into the correct position and select the right filters, you must always inspire the musicians so that something can be created. What we are seeking must always touch the musicians. They also want to receive something. This enthusiasm, this seriousness must be transferred. And this is the reason why the final version of the work is often the best one.

And it's not always easy, as Pärt's wife, Nora, explains further:

We go through hell. We're exhausted. We've reached our limits. But then, deep inside us, we hear this pure sound, which motivates us. And Manfred lives it with us.

It takes a very specific vision to be able to transcend genre and know exactly what the music needs, and this may well mandate a quality construable as controlling, but how could Eicher not be, when he's created a life's work as rich and varied as the ECM discography? Eicher is involved in the music at a level that few other producers are, yet far too many artists describe Eicher in egalitarian terms for such accusations of dictatorship to hold water. Yes, he knows what he wants, and there are artists for whom his vision is not a shared one, artists like guitarist Pat Metheny, who ultimately left the label, but not until it had helped him establish an international reputation. Others leave the label after longer stays but, like Metheny, the parting is invariably more about taking full control over all aspects of their music, as with bassist Dave Holland, when he left the label after nearly 30 years to start his own Dare2 imprint.

But what of artists like Jarrett, Rypal, Garbarek and guitarists John Abercrombie and Ralph Towner, who have recorded with Eicher for four decades? What of those, like Chick Corea, who continue to return to the label when a specific project seems right for it (like the pianist's recent duo recording with Stefano Bollani, 2011's Orvieto)? And what of others still, like Charles Lloyd, who have their careers revived by Eicher, leading to some of the most precious recordings of their careers, like the saxophonists' Athens Concert (2011)? What else can be inferred? Eicher has, indeed, a clear vision of what ECM is to represent, but that doesn't come at the expense of providing his artists—for whom, atypically in the recording industry, there are no long-term contracts, just an agreement and a handshake for each project—the freedom they need to realize their visions. The only requirement, it seems, is that these visions must, at least, share more in common than not.

Detractors hold artists like Marilyn Crispell up as an example of Eicher's apparent control, crying "foul" when, after her early career was spent in contexts more aggressive, the pianist began exploring a softer, more lyrical kind of freedom with albums such as Nothing Ever Was, Anyway (1997). Those who preferred her more outgoing expressionism may, indeed, cry foul, but there's a simple truth to be faced: were Crispell not doing exactly what she wants to do, is there any compelling reason why she would have remained with the label for nearly 15 years and five recordings? And if Eicher is regarded, by some, as imposing an aesthetic more disposed towards introspection, lyricism and space, how, then can albums like the avant-edge of bassist Michael Formanek's The Rub and Spare Change (2010), the electrified energy of guitarist David Torn's adventurous Presenz (2007), or the unrelenting density of saxophonist Roscoe Mitchell's latest with his Note Factory group, Far Side (2010), be explained?

Sounds and Silence, the film and the soundtrack CD, are certainly more emphatic of Eicher's interest in space, his disposition towards the beauty of a fully decaying note, and an unmistakable love of compelling if sometimes oblique lyricism. Their general avoidance of anything resembling traditional jazz might disturb some, and provide the evidence others are looking for to render the all-important "it's not jazz" verdict against the label, based on performances such as Dino Saluzzi and Anja Lechner's work from Ojos Negros (2007), Tunisian oudist Anouar Brahem's similarly chamber-infused Le Voyage de Sahar (2007), or the opera-informed melodrama of saxophonist/clarinetist Gianluigi Trovesi's Profumo Di Violetta (2008). When Keith Jarrett—who is the closest of anyone here to a "real" jazz performer—is heard in the recital context of Sacred Hymns, and the most overt improv comes from percussionist Marilyn Mazur and her Elixir (2008), what does it say about Eicher?

It says about Eicher what is relevant and broadly applicable, regardless of musical context. It provides a window into the working process of a producer who's as comfortable in the relative mainstream of saxophonist Lee Konitz's date with pianist Brad Mehldau, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Paul Motian (2011's Live at Birdland) as he is the cinematic expanse of Finnish pianist/harpist Iro Haarla (2011's Vespers); equally, Eicher has no problem moving from a Steve Kuhn session (the pianist's 's 2009 title-says-it-all Mostly Coltrane), to a date where Trio Mediaeval returns to sacred texts (2011's A Worcester Ladymass).

For Eicher, genre doesn't matter; nor does compartmentalizing music into neat and tidy categories. What matters is the music—ensuring that the best possible performance is captured. What matters is creating a context that encourages uninterrupted engagement from the artists, and a recording process that captures each and every note with absolute accuracy while remaining unobtrusive to the musicians rendering those notes. What matters is creating a final package that, when put in the hands of the consumer, is more than just a silver disc with digital bits and bytes, It's a piece of art, from the design of the cardboard sleeve and the artwork, photography and sometimes liner notes of the CD booklet, to the music itself, presented with the kind of pristine clarity that allows every note be heard, from initial silence to final decay.

There may still be plenty we don't know about Manfred Eicher, but through 87 minutes of Sounds and Silence: Travels With Manfred Eicher—its beauty and absolute verisimilitude begging for repeat watches—there's plenty to be affirmed, plenty to be learned, and plenty still left unanswered. And that's exactly as it should be.

Sounds and Silence: Travels With Manfred Eicher (DVD)

Production Notes: Feature Film (87:00). Special Features: Theatrical Trailer (1:30); Manu Katché Playground EPK (6:43).

Music for the Film Sounds and Silence (CD)

Tracks: Reading of Sacred Books (Gurdjieff); Für Lennart in memoriam (Oärt); Arpeggiata addio (Kapsberger); Modul 42 (Bärtsch); Sur Le Fleuve (Brahem); Creature Walk (Mazur); Tango a mi padre (Saluzzi); Farewell Theme (Karaindrou); To Vals Tou Gamou (Karaindrou); Ojos Negros (Greco); Cosi, Tosca (Puccini, arr. Arnoldi); Readings of Sacred Books (Gurdjieff); Da Pacem Domine (Pärt).

Personnel: Keith Jarrett: piano (1, 12); Tallinn Chamber Orchestra (2, 13); Tõnu Kaljuste: conductor (2, 13); Rolf Lislevan: archlute and baroque guitar (3); Arianna Savali: voice (3); Pedro Estevan: percussion (3); Thor-Harald Johnsen: chitarra battente (3); Nik Bärtsch: piano (4); Sha: bass clarinet (4); Björn Meyer: bass (4); Kaspar Rust: drums (4); Andi Pupato (4); Anouar Brahem: oud (5); François Couturier: piano (5); Jean-Louis Matinier: accordion (5); Marilyn Mazur: percussion (6); Dino Saluzzi: bandoneon (7, 10); Anja Lechner: violoncello (7, 10); Jan Garbarek: tenor saxophone (8, 9); Kim Kashkashian:viola (8, 9); Eleni Karaindrou: piano (8, 9); Camarata Orchestra, Athens (8, 9); Alexandros Myrat: conductor (8, 9); Gianluigi Trovesi: alto saxophone (11); Filarmonica Mousiké (11); Savino Acquaviva: conductor (11); Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir (13).

Photo Credit: Stills taken from Sounds and Silence: Travels With Manfred Eicher, courtesy of ECM Records.

Tags

Manfred Eicher

Profiles

John Kelman

ECM Records

Keith Jarrett

Mal Waldron

Paul Bley

Marion Brown

Chick Corea

Stefano Bollani

Craig Taborn

Stefano Battaglia

Jan Garbarek

Arild Andersen

Terje Rypdal

Jon Christensen

Trygve Seim

Mathias Eick

Jon Balke

Ketil Bjørnstad

Nils Petter Molvær

Food

Charlie Haden

Nik Bartsch

Per Jørgensen

Samuli Mikkonen

Arvo Part

Dino Saluzzi

Anja Lechner

pat metheny

Dave Holland

John Abercrombie

Ralph Towner

charles lloyd

Marilyn Crispell

Michael Formanek

David Torn

Roscoe Mitchell

Anouar Brahem

Gianluigi Trovesi

Marilyn Mazur

Lee Konitz

brad mehldau

Paul Motian

Iro Haarla

Steve Kuhn

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.