Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Nat Hentoff: The Never-Ending Ball

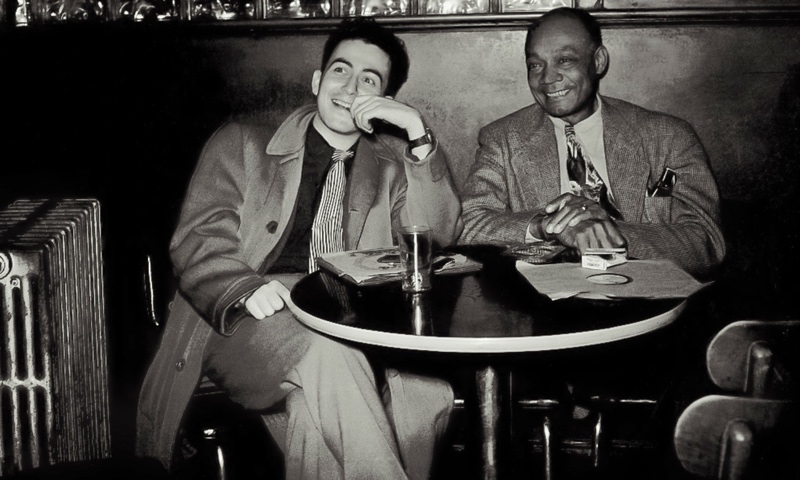

Nat Hentoff: The Never-Ending Ball

Nat Hentoff was eleven years old when, walking down the road one day in Boston, he heard music so exciting that he shouted with pleasure and ran into the shop to learn that the music was of clarinetist Artie Shaw. In that moment was born a love affair with jazz which has lasted seventy-four years thus far. At nineteen, Hentoff was hosting his own jazz radio program, and by the age of twenty-eight he was an editor of Downbeat Magazine, which was to fire him in 1957 for hiring a staff person of color. Over the years he has written for a number of the most prestigious publications in America, and has authored a large number of books, many pertaining to his passion for jazz.

His impassioned writing for over half a century on issues such as civil liberties, criminal justice, health and education have earned him a reputation as one of the foremost chroniclers of American politics. One thing is for sure, in his writing Hentoff never sits on the fence. He has received a large number of awards over the years for his literary contributions in the fields of law, journalism and jazz and in 2004 he became the first non-musician to be designated a NEA Jazz Master. With modesty, and probably in all seriousness, Hentoff says that the greatest award he has ever received was a kiss of gratitude from Billie Holiday.

His latest book on jazz, At the Jazz Band Ball: Sixty Years on the Jazz Scene (University California Press, 2010) brings together his writings from various publications over the last decade, most notably JazzTimes and The Wall Street Journal. These sixty-four essays and articles read like a colorful potted history of jazz in America, and are peppered with rich anecdotes and first-hand stories from the mouths of the great jazz artists that Hentoff knew personally. Hentoff said, in a recent JazzTimes column, that it may be his last book on jazz, but like the musicians he writes about he too has the calling, and, driven by a passion that was sparked by the clarinet of Artie Shaw all those years ago, it is just as likely that it won't be. As Hentoff says about the music which has fulfilled him and inspired him all his life: "You just can't hold it back."

All About Jazz: There are several recurring themes in your writing in this collection and one is jazz as a life force, and musicians as the carrier of this life force. I know you're an atheist, but does it ever strike you that there is a strong element of religion about jazz?

Nat Hentoff: Well, you can have a secular religion that doesn't require a belief in God; I believe in the First Amendment for example, my right as a citizen to do what I'm going to do when I write an article calling the President of the United States a liar, because he promised there would be no rationing of health care under his leadership and he has just appointed the head of the Medicare committee that will do just that. I quote him directly; he's "in love with the British system," which is the worst kind of rationing. There's a waiting list of seven hundred and fifty thousand there to get to see a doctor and there's a lot of them are going to die, so I can't keep quiet about that.

Jazz as for life force? I can give you a recent story. Last Saturday I was working as usual and I was very low, for various reasons, and then I remembered what to do; I had a new release here by James Moody and I put it on. As soon as the music started I burst into tears and they were tears of delight. That's happened to me once in a while, it's just a release. As usual, Moody makes you feel the life force.

AAJ: Has there ever been a time in all the years when you thought you might have lost faith in jazz—say with the advent of the avant-garde or with the conversion of so many jazz musicians to jazz rock and jazz fusion?

NH: When I was a teenager way back, there was always a small group of people of my age in various parts of the country who heard jazz and they were hooked for life. When rock came I was worried because it took over the whole generation practically. I mentioned this to Teddy Wilson, the prominent pianist and he said: "Don't worry, because even if they open their ears to rock they have ears which are attracted to music, and eventually a few of them are going to be open enough to go into jazz."

I never lost faith in the continuation of jazz because there are always young players. One day I was pulling out some records and I came across one, [Confeddie (Self Produced, 2009)] I'd never heard of this young woman, she's twenty years old and her name is Hailey Niswanger. She's a student at the Berklee School of music. I heard the first few bars and I thought "Wow, remarkable! I'm going to write about this." There are always going to be people like that.

I do admit that the enchantment of fusion rock, electronic rock by Miles Davis, cost me a friend; we had been very friendly but when I heard Bitches Brew (Columbia, 1969) I wrote about it very negatively. I figured Miles had enough electric wattage without this stuff and he never forgave me for that [laughs].

AAJ: There are many great examples in your book of the power of jazz as a life-force; do you have a particular favorite from this collection?

NH: When Francis Sweeney died—she was the woman in Boston who first brought me into reporting —Boston, then—and this should have been documented—was really the most Anti-Semitic city in the county, and if you were a kid in the ghetto and you went out at night you'd lose some teeth. People would be after you as a Christ killer and I lost some teeth. When I was fifteen or so this woman Francis Sweeney, a devout Catholic, ran a newspaper that exposed corruption in politics—that was easy—but she was also angry with the church because it said nothing about the anti-Semitism going on. She got me involved in some reporting on this. When she died I was very, very low and the only way I could do anything was to play Ben Webster ballads, all day long. My mother thought I was crazy, but that worked for me.

AAJ: One story from the book that really struck me was the story about Louis Armstrong in the Congo; where did you first hear that story? It sounds unbelievable.

NH: There was a big day at Queens, a borough of New York, when the Louis Armstrong home and museum was dedicated as a national landmark. I was there with people from all over the world, and all the kids from the neighborhood—there's a Louis Armstrong Elementary School there, and a Louis Armstrong Intermediate School there. When Louis was there the kids would come see him and talk to him about the music. They also knew that when they were there and the ice cream wagon came along he'd take care of that.

As we're all gathered there in the street, all of a sudden, from way up high on a balcony beside Louis' den where he used to have his notebooks and play music, there was Jon Faddis playing a capella, all alone, "West End Blues."It was one of the most thrilling things I ever heard. Then Jon told the story; he said there was a fierce civil war in the Belgian Congo, this is in '53, and the two warring parties called a temporary truce because the leaders had found out that Louis was booked for a concert in the Belgian Congo. I thought it wasn't surprising to me that they stopped a terrible war to hear Louis.

AAJ: [laughs] That's such an amazing story.

NH: I'll tell you something else, Phoebe Jacobs, a close friend of Louis and Lucille , runs the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation which has done so many things; they have funded a Louis Armstrong Music Therapy Program at the pediatric center at Beth Israel Hospital in New York—Louis always thought music was good for the health to help people recover. Phoebe was there on this big day and she says: "You know, people say Louis Armstrong is dead; Louis' not dead." That's true of all these people who are supposedly dead but their music stays very much alive.

AAJ: Absolutely. Another theme which is central to At the Jazz Band Ball is jazz as an educational force. Promoting education is something very dear to your heart but how do you think studying jazz can benefit young people today?

NH: In Sarasota Florida there's a very active jazz society and there's a woman who teachers in Florida, she grew up in Harlem, called Lucy White; she used to hear Chick Webb and all those people back then. When she came to Florida to be a teacher she was trying to get the schools to put jazz in the curriculum and she finally succeeded. Fifth grade classes in twenty elementary schools include American history intertwined with the history of jazz—the whole black migration from the south to places like Chicago, the role of New Orleans, the role of jazz in the Civil Rights movement, and all of this is part of the history of America as taught in the schools. One of the results, among other things, is that some of the kids in the classes began to form their own small combos. It's very infectious.

I received an invitation to a fourth grade class here in Manhattan and they asked me to play the kids some jazz and talk about it. So, one of my favorite musicians is the New Orleans clarinetist George Lewis, and I brought along one of his CDs, George Lewis and His New Orleans Stompers (Blue Note, 1955). I played a few bars and the kids got up and they started to dance, and pretty soon the teacher got up and she started to dance. The music really gets to you. The music does bring life. You can call it American music and all that but it happens anywhere in the world.

I once got a smuggled message from a tenor player in Moscow—this was when Stalin was in charge in Russia and, of course then, jazz was banned. Somehow this tenor player in Moscow got this message out and it came to me a circuitous way. He had heard that I knew [John] Coltrane and had written some liner notes and the message was, could I send him some liner notes on John Coltrane. Well, I found out how to do that. Even under Stalin the music was so important to this guy he took a big chance.

AAJ: That's remarkable. Something else that comes across in the book is the willingness of the elder jazz musicians, people like Dizzy Gillespie in his day, Clark Terry and Phil Woods to name but a few, to give of themselves to younger musicians. Do you think the same spirit of generosity, this passing of the torch if you like, is alive and well with the modern generation of jazz musicians?

NH: Oh sure, you see your first question was is jazz a religion?; I've seen these young jazz musicians like Hailey Niswanger and Aaron Weinstein—a young musician in his early twenties who plays hot jazz violin—and they're always eager to share with young people; that's been the whole history of the music.

I used to hang out at the Savoy in Boston when I was a kid, and Frankie Newton, a wonderful trumpet player—a black guy who was very race conscious and, like Miles, would react to any anti-black feeling if he found it, but he was also a guy who wanted to pass on the music. Some white kid asked him if he could take lessons with him and what it would cost, and Frankie said: "Well, if you're interested in this music I won't charge you anything."

Then there's the story about Clark Terry, who's playing in Seattle when Count Basie had a small combo, and this young kid turns up, as thin as a stick, but he's a serious young kid and he's trying to learn trumpet and could he study with Clark? So Clark says: "Look, the only time would be after a long night if you want to come by at six in the morning before I go to bed." The kid said sure. The kid's name was Quincy Jones.

AAJ: That's a great anecdote. In the book you describe Wynton Marsalis as "the pre-eminent jazz educator of our times," and yet you have also been critical of him for his failure to employ women in the Lincoln Centre Jazz Orchestra.

NH: Wynton Marsalis has yet to employ a full-time woman in the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis. Women musicians are very aware of how blind Wynton is to this, and a few years ago they had a demonstration outside the Lincoln Center and one of the women had on a big sign saying: "Testosterone is Not a Musical Instrument."

AAJ: You suggested a few years ago that he employ blind auditions; did he ever took you up on that?

NH: Not that I know of. I should say though that when he gets on television he is just like Leonard Bernstein, and there ought to be more of that. There's very little jazz here on radio or television.

AAJ: On the subject of women in jazz, you write about an important but perhaps largely ignored women's jazz band, The International Sweethearts of Rhythm, who were together for about eleven years in the ' 30s and '40s; do you know of any live recordings that have surfaced over the years?

NH: There have been a few but I'm surprised there hasn't been a box set. They had some musicians, and I've talked to players who were contemporaries of theirs like Coleman Hawkins, who said that some of their players were at least the equal of many leading male players.

AAJ:It seems that there are still relatively few women jazz artists who play an instrument other than the piano or singing; do you see it that way?

NH: No, that used to be the case but it's no longer the case. There are a lot of women players now. One of the stimuli for this is Diva, which is an all-woman band directed by Sherrie Maricle; she's a percussionist, she teaches at New York University. My goodness, some of those players will out swing almost anybody. They have a number of recordings and they play the college circuit. Sherrie tells me that there is great interest from budding young women musicians and that swells the numbers. It's growing all the time.

AAJ: There's a wonderful portrait of the great singer Anita O'Day in At the Jazz Band Ball ; do you think the art of jazz singing is alive and well today?

NH: I don't know that there are any Anitas around. I would say that there are too few. I don't know why that is but then again there's no Jimmy Rushing around either or any of the really good blues singers. The whole vocal scene is worse than it was; I don't know why that is but I'm hoping it will change. There are some around like Catherine Russell, daughter of Carline Ray of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm. She is superb; she's now in her fifties.

AAJ: A question which arises now and again in At the Jazz Band Ball is whether or not jazz has a healthy future and you seem to be quite optimistic, no?

NH: Well, like I've said in part already; there are always young musicians who have to play, and they have a calling, they have to play the music. Then there are players who also teach like Benny Golson, like Clark Terry, who can hear the potential and out of it comes someone like Hailey Niswanger. It's just the way Ruby Braff started; he was a kid in Boston listening to jazz and he'd take his cornet and play along with the music. You just can't stop it. Sidney Bechet said, in a very good book he wrote called Treat it Gentle (Twayne, 1960): "You cannot hold back this music."

Duke Ellington told me: "Don't give me these terms like modern jazz or cutting edge; it's the individuals who make the difference" he said, and if you have enough of them you have a band.

AAJ: That's a great answer, however in both the USA and in Europe musicians constantly bemoan the lack of gigs and the difficulty of getting gigs; if there aren't enough gigs you've got a lot of unemployed musicians, no?

NH: Oh yeah, well as you know what they euphemize by calling it a recession means there are people all through the economy here who will never get jobs like the ones they had, and some of them may never get jobs. The whole world economy seems to be tanking, from Japan to Germany to the United States, so it's going to be harder. However, when nothing much is happening there's a small club somewhere where you don't get much bread or you get only what they collect at the door, but they don't stop. There's a place in New York called Smalls; it's not a very large place, it's here in the Village, where I live, and all kinds of people have started there and in just a few years wind up with record contracts. In answer to the previous question there is no way of stopping it, you're not going to make a lot of money but as long as you can find a way to eat it doesn't matter.

One of my favorite people and musicians was Jimmy Rowles, a master pianist and accompanist; he played for Billie Holiday and a lot of other people. I asked him one day "What happens in terms of gigs? There must be times when nothing's happening?" He says: "Yeah, that's right." I said: "What do you do?" He said: "I wait for the telephone to ring."

AAJ: There are many tremendous characters of the jazz scene in your book and one who is mentioned just in passing is Willis Conover, of The Voice of America fame; he was a little known name in the US but very well known in Eastern Europe and you described him as "the single most effective evangelist in the history of the genre;" what was his importance in jazz?

NH: Oh Willis Conover, that was an extraordinary illustration of what can happen when you have somebody who can communicate and reach a large part of the world where he had people listening. The Voice of America then thought pretty highly of jazz and Willis had programs all the time; he knew all about the music, he loved the music.

AAJ: I've read that Conover had as many as thirty million regular listeners to his jazz programs in Eastern Europe at the height of the Cold War.

NH: He was like a colonizer. We don't have anything quite like that now. In this country even the National Public radio which does a pretty good job of reporting and all that, they have very little jazz. On television the Public Broadcasting System has no regular jazz programs at all.

AAJ: In '60/'61 you oversaw the recording of forty or so records for the Candid record label, including Pee Wee Russell, Coleman Hawkins and Max Roach. If you had the same freedom today as you had then to record any of today's jazz practitioners you wished, who would you like to let loose in a recording studio?

NH: I think I would do all ages. There are some very good players around who still don't get much attention, they may be in their eighties and nineties but still have so much to say, [James] Moody being one. If I had the record company to do that I'd get out more; my day job is rough. I spend a lot of time on a syndicated column which goes out to about two hundred papers and I have to cover breaking news, most of which is terrible these days. The first thing I'd do which I used to do as a kid is I'd ask musicians I knew: "Hey, who's making it? Who's coming up?" They are the best critics.

Probably the most fulfilling thing I've ever done in my life was being able to send out into the world not only Coleman Hawkins and Pee Wee and Charles Mingus, who was my good friend, but Booker Little, who died much too soon. It's one thing to write about it, and I know that some people have benefitted in that they began to listen, but to send the music out is almost as good as playing it. Not quite, but I had a great satisfaction in that.

AAJ: You make a very interesting observation in this book about the tail end of John Coltrane's career, and that is that although many whites didn't get his music the blacks were going to see him at his concerts. Then you had people like Phillip Larkin who never missed an opportunity to stick a literary knife into Coltrane. What do you think Coltrane's latter day music communicated to a black audience that the white folk maybe didn't pick up on?

NH: Art Davis, the great bassist told me—and I used to see this at a place called the Village Gate where John would play one number for two hours—the crowd which was black, white, whatever, would be going like they were at a church.

AAJ: Could you understand Larkin's hostility to Coltrane's music?

NH: He was a poet; I didn't pay much attention to him as a jazz writer. I'll tell you something about John, it's in the book. There's a wonderful second grade teacher in Queens, the borough in New York where John lived in his last years and where he did a lot of his composing; this second grade teacher loved the blues and she began to listen to jazz and Coltrane really reached her. She'd already gotten the kids listening to all kinds of music and then she started to play Coltrane. The kids really got excited and they wanted to hear more and more. The Principal of the school heard about this and they had a school-wide program where the kids tried to show in their dancing what the music meant to them. I wrote about this in the Wall Street Journal and the result is that this teacher is now a teacher at Jazz at Lincoln Center. She teachers at other places and her whole life now is teaching Coltrane, and mostly to young people.

AAJ: Another musician with a very individualistic sound is Cecil Taylor; I was struck by a story in your book which describes Jo Jones showing his displeasure at Taylor's music one night at Birdland by throwing a cymbal onto the stage and gonging him off...

NH: That was amazing because I knew Jo very well and he loved the music and tried to encourage what he called his "kiddies." The story with Cecil was [when] Cecil was unknown; he was gigging wherever he could and he sat in at Birdland and sometimes the guys just wouldn't listen, and Jo did indeed take a cymbal and throw it across the stage.

This happened too, though not with a cymbal, to Ornette Coleman; the first time he came to New York he played a place called The Five Spot. Most of the older players came to listen to him because there had already been a fair amount of publicity about him. I was sitting next to Roy Eldridge one night and Roy was always open to all kinds of things and he said to me: "This guy's just jiving, there's no music in there." Even Coleman Hawkins, who was the first of the swing masters to have Dizzy [Gillespie] on one of his recordings, said: "I don't like to say anything negative about somebody but this guy needs a lot of seasoning." Ornette had already had the experience in Los Angeles when he came on the stage for some all-star thing where he was just sitting in, and all the other players walked out. He was hurt by that.

AAJ: Hardly surprising. People talk about the" Golden Age" of jazz, but these stories about the hostile reaction to Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman strike me as being ungracious in the extreme; there isn't that level of intolerance in the jazz scene today, is there?

NH: Well, it's like writers —different people have different ways of reacting. One thing I learned from Charlie Parker about listening, when I interviewed him on the radio, and it's helped me a lot, Bird said: "I heard a [Béla] Bartók concerto and I didn't like it at all. Then I was in Paris and I heard the same thing and I thought wow, and I decided to write a concerto for jazz musicians like that." He said: "Never listen to something just once."

I think too many of us, including some musicians maybe, make the mistake of listening just once. Sometimes how you react to music depends on whether you've had a fight with your girlfriend the night before or you have indigestion.

AAJ: Your own credo has always seemed to be that if you've got nothing good to say about the music, then say nothing; you're very aware of the responsibility of being a jazz critic, aren't you?

NH: Gee, I don't see myself as a critic. I used to have to review a lot of recordings when I was at Downbeat and it always bothered me writing something that might help the guy lose some of his work. So, when I finally got fired at Downbeat and went over to The Wall Street Journal and JazzTimes, I decided to only write about those musicians who really get to me. I'm not a musicologist, I can't tell you what the chords are, what the polyrhythms are; and that bothered me for a while.

One day one of my daughters, Marinda—who's a pianist, a teacher and a singer—really hit me once when she said: "How can you be negative when you're taking away the bread from somebody and you can't even tell what he's doing?" I brooded about that. Well, I was walking down the street where I live in The Village and I saw Gil Evans coming. I knew Gil when he was still with Claude Thornhill and I'd been with him at the Miles Davis sessions, and I decided I'd make him my Rabbi; I told him what was bothering me and he said: "Hey listen, I know musicians who can tell you everything that's going on technically but they don't get inside the music to the story the musician's trying to tell. I read you, you get there some of the time. Stop worrying."

I felt a little better after that, but I decided, to hell with all this, I'm only going to write about musicians that people will want to listen to because of what I write.

AAJ: I was a little surprised to read a JazzTimes article from '01, about Diana Krall and Jane Monheit, in which you basically discredit them as jazz singers...

NH: I'm not an absolutist; when something is so hyped, so publicized that it is way out of line with what is actually being sent out as jazz I had to say something. That's why I wrote that column about Monheit and Krall; they weren't in the same universe as Billie Holiday or Anita O'Day, or Carmen McRae, my goodness! So I have to say I broke my rule on that one.

AAJ: Another fascinating article from JazzTimes that's included in this book is "Satchmo's Rap Sheet," which talks about the FBI's monitoring over many years of Louis Armstrong's alleged Communist sympathies. You co-authored a book in '74 called State Secrets; Police Surveillance in America (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1974); did it come as a surprise to you to later learn that the FBI had also been keeping a file on you over the years?

NH: Not really. Don't forget I was young enough to have been around when Joe McCarthy was finding Communists all over the place. There's always been this undertow in this country because back in the '20s, when the Bolsheviks had taken power in Russia the then Attorney General rounded up hundreds of people, citizens, and threw them out of the country. And the young man who helped him was a man called J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover started the FBI and all that. So no, I wasn't surprised. I was somewhat amused because one FBI file I finally found had me at a meeting of —quote—"radicals" —unquote—in North Africa. I'd never been to Africa, North or South. There was all kinds of other jive in there. I want to get an update on my current file but so far they won't give it to me.

AAJ: Can you understand why jazz musicians and jazz music have never been properly honored or fully appreciated in the United States?

NH: Well, that's a good question. When Obama was going to be inaugurated—before I knew how hollow a man he was—I was very taken by the fact that there was a concert the night before with Wynton Marsalis, and then Justice Sandra Day O'Connor of the Supreme Court making a point of how important jazz had been in the Civil Rights movement and all through American history; but that didn't mean that any of that followed with any enthusiasm in Congress or anything else.

We have one guy in Congress, John Conyers, who's Chairman of the Judiciary Committee; he grew up in Detroit and knew the Detroit jazz scene but most of these guys are squares. There's very little of this in the schools. Quincy Jones is now trying very hard to get jazz, all music, into the schools. But you know, I don't think there's much interest now in Johann Sebastian Bach who really was a swinger, or in Bartók, or Gregorian chant, which is beautiful stuff. In terms of music this is an undereducated country to a large extent, but at least with jazz more and more young people are getting to play it. There's the annual Duke Ellington contest that Jazz at Lincoln Center does; Charles Mingus' wife, Sue Mingus has just started a Mingus contest at Julliard in New York, so High School kids throughout the country will be playing Mingus music. By the way, Charles always used to say: "I don't play jazz, I play Mingus music." So I have some confidence. It keeps the music alive.

AAJ: The Pulitzer Board awarded a special citation, somewhat tardily, to Thelonious Monk in 2006, in recognition of the importance of his music, and Ornette Coleman in 2007, and to Coltrane as well I believe—and also to Bob Dylan and Hank Williams in recent years; do these citations give you hope that jazz is finally getting some of its due or do you think there's an element of tokenism about them?

NH: I'll give you an original tokenism story; before the people you mentioned there was going to be a Pulitzer award for Duke Ellington, a kind of "well, he's been around for a long time" thing, but then they snatched it away.

AAJ: The Pulitzer Board overturned the decision to award Ellington and recognize the seriousness of his music, didn't they?

NH: They did, and two members of the jury resigned in protest. Well, Duke said in public: "Fate doesn't want me to be too famous too young [he was sixty-six]." The next day, I talked to him and he was furious. Since then the only person I can think of who got an actual Pulitzer Prize for composition was Wynton Marsalis, and that was a very long, overblown piece of music. I guess they had seen him on television, and that must have impressed them.

I'm of an age when I think to hell with them, who needs the token awards? What counts is, does the music stay alive? Well, nobody mentions Benny Carter anymore or Bill Jackson and I could name names for days, but this music is never going to die. Once you get involved as a listener, it's really for the rest of your life.

AAJ: What, in your opinion, can be done to increase the jazz audience in the US?

NH: I wrote a recent column for JazzTimes , which was about a Public School teacher in Massachusetts called Nick Carlon. He teaches Seventh Grade English, and he also brings in jazz recordings and tells the kids who the players were and, as always happens when you expose young people to the music, they react. Some of them want to get up and dance. He told me what some of the kids are saying: "Hey, I just put Louis Armstrong's "West End Blues" on my iPod"; when that happens you've got more of an audience coming up. Is it going to be a huge audience? Probably not, but what the hell, as I said before, even Bach doesn't have a huge audience anymore.

AAJ: Nat, you were let go by The Village Voice at the end of '08, after fifty years of service; that must have been a hard blow to take, no?

NH: It surprised me a little, but what the heck, I've been fired from some of the most prestigious publications in America. I was at The New Yorker for many years, I was fired there. I was at The Washington Post for fifteen or sixteen years. It's a long list. Sometimes I tell young reporters: "Don't get down, there's always something going on."I finally wound up at the Cato Institute in Washington. It's a libertarian place; I write for them and I use their enormous research resources. Finally Tony Ortega, the editor of The Village Voice asked me to come back—at least once a week or so—and that's okay, because one of my big passions is education and I've covered the Public School system in New York since the '50s. So that's what I write about for The Voice.

I've got so much to write about; I still have my column, which is syndicated around the country, I write about music for The Wall Street Journal and JazzTimes. I'm working on a book called Is this America?, which I don't think either Dick Cheney or Obama is going to like. I'm about to turn eighty-five and I've never had so many deadlines.

AAJ: You've known, befriended and interviewed many of jazz's greats; is there anyone you regret not interviewing?

NH: I'm sure I missed some of them and I'm sure at two in the morning I'm going to be haunted by this question. I knew a lot of them even though I didn't have the space or the time to interview them. To me, knowing them made their music come even more alive.

AAJ: What advice would you give to aspiring young jazz writers?

NH: Until recently I did interviews at a club here in New York, called The Blue Note, for television, and I would ask interviewees about that and they invariably said journalists have to know more about music; well, that takes care of me. Sure, you really ought to try to learn more but the main thing is to listen. Duke Ellington once said something to me: "You know, I don't want people [who] listen to our music to analyze it, I want them to open themselves to the music and feel it." That's the way to listen, and then you begin to be able to feel it and if you can put this into words then you've contributed something.

Tags

Nat Hentoff

Interview

Ian Patterson

United States

Massachusetts

Boston

Artie Shaw

Billie Holiday

James Moody

Teddy Wilson

Hailey Niswanger

Miles Davis

ben webster

Louis Armstrong

Jon Faddis

Chick Webb

John Coltrane

Dizzy Gillespie

Clark Terry

Phil Woods

Frankie Newton

[Count] Basie

Quincy Jones

wynton marsalis

Wynton [Marsalis]

Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra

Leonard Bernstein

Coleman Hawkins

Sherrie Maricle

Anita O'Day

Jimmy Rushing

Catherine Russell

benny golson

Ruby Braff

Sidney Bechet

duke ellington

Jimmy Rowles

Pee Wee Russell

Max Roach

Charles Mingus

Booker Little

Art Davis

Cecil Taylor

Jo Jones

Ornette Coleman

Roy Eldridge

Charlie Parker

Gil Evans

Claude Thornhill

Diana Krall

Jane Monheit

Carmen McRae

Thelonious Monk

Benny Carter

Bill Jackson

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.