Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer

Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer

Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer

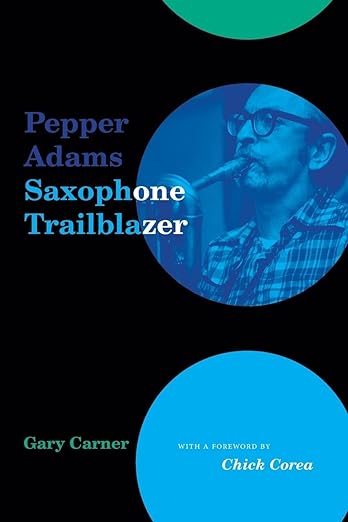

Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer Gary Carner

240

ISBN: #9781438494357

Excelsior Editions

2023

Baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams was essential to this reviewer's formative years as a jazz enthusiast. During the 1970s, in Storrs, Connecticut, New York City, northern New Jersey, and Kansas City, Missouri, I had many opportunities to witness Adams's blazing talent. Regardless of the setting and the capabilities of the musicians surrounding him, he was always on. It was heady stuff. Lengthy improvisations were the rule. Challenging and rewarding in equal measure, his virtuosic, rapid-fire, bop-oriented flights demanded full attention, commitment, and mindfulness. It was not unusual to feel sated, exhilarated, and utterly exhausted at the end of a performance. Adams invariably took charge and did not let up—yet the excitement he generated never overshadowed the architecture, intelligence, and wit of his impromptu lines.

Gary Carner's Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer tells the story of a complicated individual within the context of jazz in America during the mid-to-late twentieth century. The book's origins lie in Carner's extensive interviews with Adams two years before he died in 1985 at the age of 55. In the years following Adams's passing, Carner interviewed approximately 250 of his colleagues and admirers, created the website, produced a box set of "Adams's entire oeuvre" performed by selected artists, as well as an annotated discography before beginning to write the book in earnest in 2017.

In his mid-teens, Adams was already becoming an accomplished tenor saxophonist when he fell in love with the baritone. While Harry Carney of the Duke Ellington Orchestra paved the way for playing jazz on the unwieldy instrument, it nonetheless was mostly relegated to section work and, according to Stanley Crouch, was widely regarded as possessing... "the stand-off qualities and the resistant fury of a stallion that dares you to break him."

Mindful of Carney's accomplishments and inspired by Charlie Parker, Adams took it upon himself to bring the baritone into the sphere of bebop. Nothing if not ambitious—at least in terms of performing—he aspired to be an original, to "stand apart from everyone else" as a soloist in jazz combos. "I thought I had the chance to do something completely different." Thus began an intensive, ten-year period in which Adams ceaselessly studied, practiced, jammed, and toiled, mostly in small bars and clubs, before moving from Detroit to stake his claim in New York City.

At a time when many others settled for a smaller, tenor-like tone and less-than-complex lines, he succeeded in getting an uncommonly large, full sound and executing complicated figures from the top to the bottom of the horn. "Someone like Gerry Mulligan, and most of us," states Bill Perkins, "learned to adapt to the instrument." But "Pepper took that instrument, and he never conformed to its weaknesses."

Throughout the book, Carner makes a convincing case for Adams's unique approach to the horn and the music. In one particularly astute passage, he identifies Adams's ... "blinding speed, penetrating timbre, immediately identifiable sound, harmonic ingenuity, precise articulation, malleable time feel, dramatic use of dynamics, and utilization of melodic paraphrase." Many of Adams's colleagues weigh in on his strengths. Ray Mosca declares that "Pepper'll make you cry with a ballad." Don Palmer notes that rhythmically speaking, Adams "was as strong as anything I've ever heard." Gerry Niewood praises the "continuous invention" of his solos. And Hank Jones contends that "He would make you play. He would make you think more creatively because he was thinking and playing creatively."

Like many jazz musicians of his era, Adams lived and breathed the music for decades only to receive a smattering of financial rewards and, at best, spotty recognition. Adopting the attitude "that if he played well, better than most anyone else, the world would discover him and reward him accordingly" perhaps wasn't an ideal way to make his mark in a highly competitive field. Adams sometimes lived "a hand-to-mouth existence" but was determined to stay the course. Despite his often precarious economic state, he refused to continue to double on the bass clarinet (which would have opened opportunities for additional studio work), disdained networking and self-promotion, did not seek teaching or Artist-In-Residence positions, and turned down at least one lucrative offer to join the saxophone section of a commercial big band. Also working against him was the perception that his average looks did not make him particularly marketable, the reality that the public "generally favored higher pitch[ed] instruments" over the sound of the baritone, and the complexity of his style demanded an active listener.

Complicating matters even further was his stay of 12 years in the Thad Jones / Mel Lewis Orchestra. The band didn't work enough to provide a living wage, offered few opportunities to improvise, and ultimately postponed Adams's entry into the world of jazz as an itinerant soloist and occasional band leader. Carner suggests that Adams's longtime respect and admiration for Jones, whom he initially met and played with in Detroit during the early 1950s, was the obstacle to making the break to further his interests. Ironically, the sudden fame of the Jones/Lewis Orchestra led to the demise of a quintet co-led by Jones and Adams, an excellent band and an ideal setting for Adams's talents.

At key places in the book, Carner introduces the thorny and complex issue of American race relations relative to jazz, Adams's musicianship, and career. Carner carefully avoids landing firmly on either side of the divide or drawing conclusions. Instead, he introduces a variety of perspectives on Adams as a white jazzman, allows them to bump against one another, and, in doing so, ultimately raises more questions than answers.

Carner makes clear that Adams strongly identified jazz practice with black musicians. In an interview conducted after he moved to New York from Detroit, Adams stated, "I learned how to play jazz from black musicians," and went so far as to assert, "If you want to know how to play jazz, that's how you learn it." In response, Carner asks, "Did Adams alienate himself from the white-controlled network of agents, editors, broadcasters, and promoters by stating his allegiance to black musicians? Perhaps so."

During a decade in Detroit, Adams, accustomed to being the only Caucasian in otherwise black bands, was comfortable playing in venues with virtually an all-black clientele. At the same time, his white peers shunned him because of his large, commanding sound, chord substitutions that sometimes sounded dissonant, and an affinity for material that included songs by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn. As a result, Adams was excluded from the higher-wage gigs often given to white musicians.

After his move to New York in the mid-1950s, Adams was one of the "few white members of jazz's black inner circle." Carner quotes an impressive array of black musicians who hold Adams in the highest regard. Some of them believed that, in the words of Art Taylor, "The only thing that stopped him from being what you would call a star is that he hung out with black guys... He liked to be with guys who could play, and in this music the guys who could play are black."

Carner notes the resentment of jazz musicians on the attention lavished on Dave Brubeck by the jazz press at the expense of black pianists such as Earl Hines, Bud Powell, Erroll Garner, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk and others. Furthermore, some blacks believed that whites were getting a hog's share of the work even though they couldn't swing or really play jazz. Barry Harris, a close associate of Adams in Detroit and New York, speculated that "Maybe if he [Adams] had gone out and gotten in a nice white group, he might have made it."

According to George Coleman, Adams was also "a victim of reverse racial discrimination" because, in Carner's words, "some blacks were jealous of his excellence as a soloist." To muddy the waters even further, Carner begins the book's final chapter with a quote from Dick Katz: "He was a towering figure, and had he been black he would have been considered one of the greatest people to play jazz on the saxophone."

The year 2023 saw the publication of first-rate biographies of heavyweights Sonny Rollins and Chick Webb, as well as Henry Threadgill's (with Brent Hayes Edwards) autobiography. Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer is in the same league as the celebrated works. The care, detail and flair that Carner puts into Adams's evolution as an artist, as well as his trials, tribulations and triumphs in the often trying world of jazz performance, makes one pause to wonder how many deserving manuscripts about musicians outside of the pantheon are awaiting publication and recognition.

< Previous

Eddie Henderson At Magy's Farm

Next >

Sings

Comments

Tags

Book Review

David A. Orthmann

Excelsior Editions

Pepper Adams

Harry Carney

duke ellington

Charlie Parker

Gerry Mulligan

Bill Perkins

Gerry Niewood

Hank Jones

Thad Jones

Mel Lewis

Billy Strayhorn

Art Taylor

Dave Brubeck

Earl Hines

Bud Powell

Erroll Garner

Thelonious Monk

Barry Harris

George Coleman

Dick Katz

Sonny Rollins

Chick Webb

Henry Threadgill

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.